International response to the Spanish Civil War facts for kids

The Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) was a big conflict that drew attention from all over the world. Many people who were not Spanish got involved, either by fighting or by giving advice. Some countries, like Italy, Germany, and Portugal, sent money, weapons, and soldiers to help the Nationalist forces, led by Francisco Franco. Other countries, like the Soviet Union, France, and Mexico, helped the Republicans, also called Loyalists. This happened even after many European countries signed an agreement in 1936 to stay out of the war. Many people in democratic countries felt bad for the Spanish Republic, but they were afraid of starting a second world war. However, leaders like Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, and António de Oliveira Salazar quickly answered the Nationalists' calls for help. Tens of thousands of people from other countries also volunteered to fight, mostly for the Republican side.

Contents

International Non-Intervention Agreement

The idea of "non-intervention" was suggested by France and the United Kingdom. They wanted to stop the war from spreading and becoming a bigger world war. France was also worried that if they got involved, it might cause a civil war in their own country.

On August 3, 1936, France proposed its non-intervention plan. The British quickly agreed. Germany and the Soviet Union also agreed in principle, but only if Portugal was included and if Germany and Italy stopped their aid right away. On August 7, France officially declared it would not intervene. By August 15, the United Kingdom also banned sending war supplies to Spain. Italy and Germany signed the agreement later in August. The Soviet Union joined on August 23, with Joseph Stalin banning war exports to Spain.

Non-Intervention Committee

A group called the Non-Intervention Committee was then set up in London on September 9, 1936. Its goal was to stop people and supplies from reaching either side in the war. However, both the Soviet Union and Germany were secretly still sending help.

The committee tried to prevent aid, but it was often accused of favoring the Nationalists. In November, plans were made to place observers at Spanish borders and ports to check for rule-breaking. But then, Germany and Italy officially recognized the Nationalists as the true government of Spain. The League of Nations (an international organization) spoke out against intervention but left the problem to the committee.

By January 1937, many countries agreed to ban volunteers from going to Spain. However, Germany, Italy, and the Soviet Union still wanted to make sure their preferred side didn't lose.

Control Plan

Observers were placed at Spanish ports and borders to monitor shipments. Patrol zones were given to four nations. Italy promised not to end non-intervention.

In May, the committee noted attacks on patrol ships. Germany and Italy threatened to leave the committee if attacks continued. They returned in June, but more attacks on German ships made them leave the patrols again. This led to arguments about whether to give the Nationalists "belligerent rights," which would allow them to search ships.

By mid-1937, it seemed like all the major powers were ready to give up on non-intervention. Secret submarine attacks by Italy began in August. The committee decided that naval patrols were too expensive and would be replaced by observers in ports.

A meeting called the Conference of Nyon was held to deal with piracy in the Mediterranean Sea. France and Britain decided their navies would patrol the area and attack any suspicious submarines. The League of Nations said that non-intervention had failed. On November 6, the plan to recognize the Nationalists as a fighting force was finally accepted, but only if foreign volunteers were withdrawn.

Countries Staying Neutral (Officially)

United Kingdom and France

The British government officially stayed neutral. Their main goal was to prevent a bigger war by trying to keep Italy and Germany happy. British leaders thought the Spanish Republican government was controlled by extreme socialists and communists. So, they secretly favored the Nationalists. Most British people wanted to avoid another major war. Many were also against communism and preferred a Nationalist victory.

The British ambassador to Spain, Sir Henry Chilton, believed a Franco victory was best for Britain. The British Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, also preferred a Nationalist victory. The British navy also seemed to favor the Nationalists. For example, they allowed Franco to set up a signals base in Gibraltar, a British colony. They also shared information about Republican ships with the Nationalists.

France depended on Britain's support. The French Prime Minister, Léon Blum, feared that helping the Republic would lead to civil war in France and a takeover by fascists. Both Britain and France were very worried about Germany and Italy starting a war.

The arms ban meant that the Republicans could only get weapons from the Soviet Union and Mexico. The Nationalists got most of their weapons from Italy and Germany. Neither Britain nor France helped the Republic much. Britain sent food and medicine but stopped France from sending weapons. The US ambassador to Spain, Claude Bowers, criticized the Non-Intervention Committee, calling it "the most cynical and lamentably dishonest group that history has known."

Winston Churchill later called the committee's work "an elaborate system of official humbug" (meaning it was a big show of pretending).

After Germany and Italy left the patrols, France thought about stopping border controls. But Britain wanted to continue, so they did. Britain and France officially recognized the Nationalist government on February 27, 1939.

United States

When the war started, the US Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, quickly banned arms sales to both sides. The US officially announced its non-intervention policy on August 5, 1936. President Franklin Roosevelt publicly said the US would not send troops or money to Europe. However, he privately supported the Republicans. He worried that a Nationalist victory would increase German influence in Latin America.

In January 1937, the US Congress passed a law banning arms exports to Spain. Some people argued that arms sales to Germany and Italy should also be stopped, as their involvement meant Spain was in a state of war. But Hull doubted how much Germany and Italy were involved. In 1938, as the Loyalists were losing, Roosevelt tried to send American planes to the Republic through France.

The ban did not apply to non-military supplies like oil, gas, or trucks. So, the US government could send food to Spain for humanitarian reasons, which mostly helped the Loyalists. Republicans spent almost $1 million a month on tires, cars, and tools from American companies.

Some American businesses supported Franco. Companies like Ford, Studebaker, and General Motors sold 12,000 trucks to the Nationalists. The Texas Oil Company illegally supplied gasoline to Franco on credit. After the war, a Spanish official said that "without American petroleum and American trucks, and American credit, we could never have won the Civil War."

After the war, some American politicians said the US policy of staying out was a disaster.

Support for Nationalists

Italy

Italy sent a large group of "Volunteer Troops" (Corpo Truppe Volontarie). Benito Mussolini, Italy's leader, used these troops to achieve political goals, test new military tactics, and give his soldiers combat experience for future wars.

Italy sent over 70,000 to 75,000 troops at the peak of the war. This involvement made Mussolini more popular. Italian propaganda used the idea of fighting against anti-Catholic actions by the Republicans to get support from Catholics. The first Italian airplanes arrived in Spain on July 27, 1936.

Italian forces included soldiers, air force pilots, and navy members. About 6,000 Italians died in the conflict. Italy also sent a huge amount of supplies, including:

- One cruiser, four destroyers, and two submarines.

- 763 aircraft, including bombers and fighters.

- 1,801 artillery pieces, 1,426 mortars, 6,791 trucks, and 157 tanks.

- Millions of small arms cartridges and artillery rounds.

- Over 69,000 tons of war material.

Italian pilots flew over 135,000 hours, took part in 5,318 air raids, and claimed to have shot down 903 Republican planes. About 180 Italian pilots and aircrew were killed.

Germany

Nazi Germany also helped the Nationalists, even though they signed a non-intervention agreement. Germany formed the Condor Legion, a special land and air force. They successfully helped fly the Army of Africa to mainland Spain early in the war. German involvement grew to include bombing targets. The bombing of Guernica on April 26, 1937, was the most controversial event, killing 200 to 300 civilians. Germany also used U-boats and contributed to naval warfare.

The Condor Legion helped the Nationalists win many battles, especially by controlling the air from 1937 onwards. Spain was a testing ground for German tank and aircraft tactics. German training for Nationalist forces was very valuable, teaching them about infantry, tanks, anti-tank units, air and anti-aircraft forces, and naval warfare. About 56,000 Nationalist soldiers were trained by Germans.

Around 16,000 German citizens fought in the war, mostly as pilots, ground crew, artillery, and tank crew. About 10,000 Germans were in Spain at the peak, and around 300 were killed. German aid to the Nationalists was worth about £43,000,000 (about $215,000,000) in 1939 money.

Portugal

When the civil war began, Portuguese Prime Minister António de Oliveira Salazar was officially neutral but favored the Nationalists. Portugal had tense relations with the Spanish Republic because it supported Portuguese people who opposed Salazar's government. Portugal was very important in providing the Nationalists with ammunition and supplies.

Portugal also sent "semi-official" volunteers called the "Viriatos" (named after an old Portuguese hero). Between 8,000 and 12,000 of them fought for Franco. Portugal also made sure that supplies could cross its borders into Spain without problems. The Nationalists even called Lisbon, Portugal's capital, "the port of Castile" because it was so vital for their supplies. In 1938, Portugal recognized Franco's government and later signed a friendship treaty with Spain.

Vatican

Many influential Catholics in Spain blamed the Republic for religious persecution, including the killing of priests and nuns. This anger was used by the Nationalists in their propaganda. The Catholic Church supported the rebels and called the persecuted religious Spaniards "martyrs of the faith." They ignored Catholics who remained loyal to the Republic.

The Vatican (the head of the Catholic Church) at first did not openly support the rebels. However, it allowed high church figures in Spain to call the conflict a "Crusade" (a holy war). Nationalist propaganda called the Republic "the enemy of God and the Church" because of its anti-religious actions.

Since Western European countries didn't help the Republicans, they relied mainly on Soviet military aid. This made it easy for the Nationalists to portray the Republic as a "Marxist" and godless state. The Vatican used its diplomatic network to support the rebels. In 1937, at an international exhibition in Paris, the Vatican allowed the Nationalist display to use the Vatican flag. By 1938, Vatican City officially recognized the Nationalists.

Nationalist Foreign Volunteers

Volunteers from many other countries fought with the Nationalists. One group was the 500-strong French "Jeanne d'Arc" company, made up mostly of far-right members.

About 11,100 volunteers from countries like the Philippines, the United States, Brazil, Mexico, Hungary, and Romania also fought for the Nationalists. In 1937, Franco turned down offers for separate national groups from Belgium and Greece. Exiled White Russians also tried to create their own unit but were rejected.

Ion Moța and Vasile Marin, two leaders from a Romanian far-right group called the Iron Guard, joined the Spanish Foreign Legion and were killed in battle. Their deaths became an important part of their group's history.

Few English-speaking people fought for the Nationalists, except for some Irish volunteers. British journalist Peter Kemp served as an officer with a Carlist (a type of Spanish traditionalist) group.

International Support

Many Catholic writers and thinkers supported Franco because of the anti-religious actions by the Republicans. These included Evelyn Waugh and J. R. R. Tolkien. Others, like Jacques Maritain, at first supported Franco but later became unhappy with both sides.

Many right-wing artists and writers, such as Ezra Pound and Gertrude Stein, also supported the Nationalists.

Even though the Mexican government supported the Republicans, most Mexican people, especially Catholic peasants, preferred Franco. Mexico had its own conflict (the Cristero War) where the government tried to suppress religion, leading to many deaths.

Irish Volunteers

About 700 followers of Eoin O'Duffy went to Spain to fight for Franco. This "Irish Brigade" saw their main job as fighting communism and defending Catholicism. However, they soon became unhappy with the Nationalists' brutal methods. In February 1937, the Irish government banned volunteers from going to Spain.

Other Nationalities

Over 1,000 volunteers from other nations served the Nationalists, including Filipinos, Britons, Finns, Norwegians, Swedes, and Belgians. Chileans and Argentinians also fought for the Nationalists. They were religious Catholics who felt they were fighting a "crusade" against atheists and communists.

About 75,000 Moroccan Arabs, called Regulares, fought for the Nationalists. They were from Spanish Morocco, which was a protectorate, not part of Spain. They were feared by the enemy and civilians. Moroccans felt they were fighting a holy war (jihad) against atheists and communists. They were also motivated by money.

The Spanish Foreign Legion, which fought for the Nationalists, was mostly made up of Spanish citizens, despite its name.

Support for Republicans

Soviet Union

Because France and Britain banned arms sales, the Republican government could only get weapons from the Soviet Union and Mexico. To pay for these weapons, the Republicans used $500 million of their gold reserves. The Soviet Union also sent over 2,000 people and $81,000,000 in financial aid. These included tank crews and pilots who actively fought for the Republicans.

According to Soviet sources, many Soviet citizens who served in Spain received honors. The most Soviets in Spain at any time was about 700. In total, between 2,000 and 3,000 Soviets served. About 1,000 Soviet pilots flew for the Spanish Republican Air Force.

The Republic sent its gold reserve to the Soviet Union to pay for arms. The Soviet Union later claimed Spain still owed them $50,000,000. German estimates of Soviet aid included:

- 242 aircraft

- 703 artillery pieces

- 731 tanks

- 1,386 trucks

- 300 armored cars

- 15,000 heavy machine guns

- 500,000 rifles

- Over 69,000 tons of war material

Much of this material was bought from other countries like France, Czechoslovakia, and the United States. The Republic often paid too much or received poor quality goods.

The Soviet Union also had secret police (NKVD) operations in Republican areas. These operations included spying and other activities.

Poland

Poland sold arms to Republican Spain between September 1936 and February 1939. Officially, Poland did not support either side, but the government secretly preferred the Nationalists. The sales to Republicans were purely for money. Poland tried to hide these sales because of the non-intervention agreement. They disguised them as deals with countries in Latin America. Most of the weapons were old, but some modern ones were also sent. All were overpriced.

Polish sales were worth about $40 million. This made Poland the second-largest arms supplier for the Republic after the Soviet Union.

Greece

Greece had official diplomatic ties with the Republic, but its leader, Ioannis Metaxas, sympathized with the Nationalists. Greece joined the non-intervention policy but secretly allowed arms sales to both sides. The main company involved was Pyrkal, or Greek Powder and Cartridge Company (GPCC).

Most Greek sales went to the Republic. Shipments usually left from Piraeus, changed flags at a deserted island, and then officially went to ports in Mexico to hide their true destination. Sales continued from August 1936 to at least November 1938. The total value of Greek sales is unknown, but one author claims that in 1937 alone, GPCC sent $10.9 million worth of goods to the Republicans. The arms included artillery, machine guns, cartridges, bombs, and explosives.

Mexico

The Mexican government openly and fully supported the Spanish Republic. Mexico refused to follow the non-intervention proposals from France and Britain. Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas saw the war as similar to the Mexican Revolution.

Mexico's support was a great moral comfort to the Republic, especially since most other Latin American governments favored the Nationalists. However, Mexico could only provide limited practical help, about $2,000,000 in aid. This included rifles, food, and a few American-made aircraft.

France

France signed the Non-Intervention Agreement on August 21, 1936. However, the government of Léon Blum secretly sent some aircraft to the Republicans. These included bomber and fighter planes sent between August and December 1936. France also sent pilots and engineers to help the Republicans. In total, France delivered 70 aircraft.

Other Countries

Other countries that sold arms to the Republicans included Czechoslovakia and Estonia. Also, $2,000,000 came from the United States for humanitarian reasons.

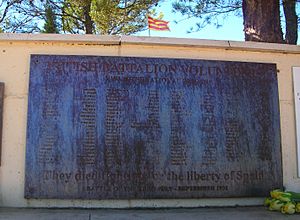

International Volunteers

Volunteers from many countries fought in Spain, mostly for the Republicans. About 32,000 fought in the International Brigades, which were organized to help the Spanish Republicans. These included the American Lincoln Battalion and the Canadian Mackenzie–Papineau Battalion. Another 3,000 fought with other groups. About 2,000 Portuguese leftists also fought for the Republicans.

"Spain" became a very popular cause for left-leaning thinkers and artists around the world. Many famous artists and writers joined the Republic's service. The war also attracted many working-class men who saw it as an adventure and a way to escape unemployment during the Great Depression. Famous people who fought for the Republic include George Orwell, who wrote about his experiences in Homage to Catalonia. His novel Animal Farm was partly inspired by the conflicts he saw among the Republican groups. Ernest Hemingway's novel For Whom the Bell Tolls was also inspired by his time in Spain.

International Brigades

Around 32,000 foreigners fought in the International Brigades. Another 3,000 volunteers fought in other Republican forces. About 10,000 foreigners also helped as doctors, nurses, and engineers.

The International Brigades included:

- 9,000 Frenchmen (1,000 died)

- 5,000 Germans and Austrians (2,000 died)

- 3,350 Italians

- 3,000 Poles

- 2,800 Americans (900 killed, 1,500 wounded)

- 2,000 Britons (500 killed, 1,200 wounded)

- 1,500 Czechoslovaks

- 1,500 Yugoslavs

- 1,500 Canadians

- 1,000 Hungarians

- 1,000 Scandinavians (half were Swedes)

- 100 Chinese

- 800 Swiss (300 killed)

About 90 Mexicans and at least 80 Irishmen also volunteered. The "Connolly Column" of the International Brigades was named after James Connolly, an Irish socialist leader.

Patriotism Against Invaders

Both sides in the war used the idea of "patriotism" to gain support. They presented the fight as the Spanish people against foreign invaders.

The Republicans, especially the communists, said that the heroic Spanish people were fighting against foreign invaders. They claimed these invaders were controlled by "traitors" from the upper classes, the church, and the army. They said the "true" Spain was the lower classes. Republican propaganda used old images that showed foreigners in certain ways. Italians were shown as weak, and Germans as arrogant. Foreign Legionnaires were shown as criminals. Cartoons often showed the rebel army as a group of foreign mercenaries. The presence of Moorish troops was used to show them as brutal and eager to steal and kill.

The Nationalists used patriotism to say they were fighting for the Spanish "patria" (fatherland) and its Catholic identity. They claimed Spain was in danger of becoming a "Russian colony" because of "traitors" and "international agents." They called the communist invaders "wolves of the Russian Steppes." Franco's propaganda showed the enemy as an invading army or puppets of foreign powers. The Nationalists explained the involvement of Moorish troops as defenders of religion against the godless supporters of the Republic. They tried to hide the presence of Italian and German troops as much as possible.

Foreign Correspondents

About 1,000 foreign newspaper reporters worked in Spain during the war, providing extensive coverage.

Images for kids

-

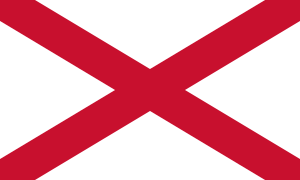

The St. Patrick's saltire flag of the National Corporate Party, an Irish fascist movement that sent the Irish Brigade to support the Nationalists.

See also

In Spanish: Intervención extranjera en la guerra civil española para niños

In Spanish: Intervención extranjera en la guerra civil española para niños

- International relations (1919–1939)

- SS Cantabria

- Palafox Battalion

- Naftali Botwin Company

- Dates of establishment of diplomatic relations with Francoist Spain

- Military forces and aid

- Corpo Truppe Volontarie – Italian expeditionary forces

- Regio Esercito Italiano – Royal Italian Army

- Aviazione Legionaria (Aviation Legion) – Italian expeditionary air force

- Regia Aeronautica Italiana – Royal Italian Air Force

- La Regia Marina Italiana – Royal Italian Navy

- Legion Condor – German expeditionary forces

- Luftwaffe – German air force

- Heer – German army

- Kriegsmarine – German navy submarine units

- Fuerza Aérea de la República Española (FARE) – Second Republic and Soviet Air forces

- Polish Brigade in Spain – Dąbrowszczacy

- Yugoslav volunteers in the Spanish Civil War

- Military operations

- Operation Ursula – Uboat

- Operation Rügen – Legion Condor

- Economic aid and dealings

- Rio Tinto Mining Concern

- Moscow gold