Ion Heliade Rădulescu facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ion Heliade Rădulescu

|

|

|---|---|

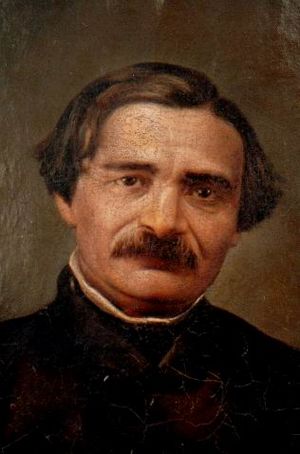

Portrait of Rădulescu

|

|

| Born | January 6, 1802 Târgoviște, Wallachia |

| Died | April 27, 1872 (aged 70) Bucharest, Romania |

| Pen name | Ion Heliade, Eliad |

| Occupation | poet, essayist, journalist, translator, historian, philosopher |

| Nationality | Wallachian, Romanian |

| Period | 1828–1870 |

| Genre | Lyric poetry, epic poetry, autobiography, satire |

| Subject | Linguistics, Romanian history, philosophy of history |

| Literary movement | Romanticism Classicism |

| Signature | |

|

|

Ion Heliade Rădulescu (born January 6, 1802 – died April 27, 1872) was an important Romanian writer, poet, and politician. He was born in Wallachia, which is now part of Romania. Heliade Rădulescu was a key figure in the Romanticism and Classicism movements in his country. He wrote poems, essays, and short stories, and also worked as a newspaper editor.

He was very good at translating books from other languages into Romanian. He also wrote books about language and history. For many years, Heliade Rădulescu taught at Saint Sava College in Bucharest, which he helped to reopen. He was also a founder and the first president of the Romanian Academy.

Heliade Rădulescu is seen as one of the most important people who helped shape Romanian culture in the early 1800s. He became well-known by working with Gheorghe Lazăr to stop teaching in Greek and promote Romanian education. He played a big role in developing the modern Romanian language. However, he caused some debate when he suggested adding many Italian words to Romanian. He was a Romantic nationalist and a moderate liberal. Heliade was one of the leaders of the 1848 Wallachian revolution, which led to him being sent away from his country for several years.

Biography

Early life and education

Ion Heliade Rădulescu was born in Târgoviște. His father, Ilie Rădulescu, was a rich landowner. His mother, Eufrosina Danielopol, was Greek. Ion was very important to his parents. His father even bought a house in Bucharest for him. The family also owned a large garden and other properties.

Ion first learned Greek from a tutor. Then, he taught himself to read in Romanian Cyrillic by studying old stories. He loved reading popular novels. In 1815, he went to a Greek school in Bucharest. In 1818, he joined the Saint Sava School, where he studied with Gheorghe Lazăr.

After graduating in 1820, he became Lazăr's assistant teacher, teaching math. Around this time, he started using the last name Heliade. He said it was a Greek version of his family name, which came from the name Elijah.

Working under Prince Grigore Ghica

In 1822, after Gheorghe Lazăr became ill, Heliade reopened Saint Sava School. He taught there without pay at first. Other smart people, like Eufrosin Poteca, joined him. He even started an art class. This was possible because Prince Grigore IV Ghica wanted to encourage education in Romanian. The Prince said that teaching in Greek was "the foundation of evils."

In the late 1820s, Heliade became involved in cultural projects. In 1827, he and Dinicu Golescu started the Soțietatea literară românească (Romanian Literary Society). This group wanted to turn Saint Sava into a college and open more schools. They also wanted to start Romanian-language newspapers and end the government's control over printing. This society was based on ideas from Freemasonry, and Heliade became a Freemason around this time.

In 1828, Heliade published his first work, a book on Romanian grammar, in Sibiu. On April 20, 1829, he started printing the newspaper Curierul Românesc in Bucharest. This newspaper was very successful. It published articles in both Romanian and French. From 1836, it had a special section for literature called Curier de Ambe Sexe. This section published one of Heliade's most famous poems, Zburătorul.

In 1823, Heliade met Maria Alexandrescu and they fell in love and married. Sadly, their first two children died when they were babies. They later had five more children.

Printer and court poet

In October 1830, Heliade and his uncle opened the first private printing press in Wallachia. It was on his land in Bucharest. One of the first books he printed was a collection of poems by Alphonse de Lamartine, translated by Heliade. He also translated works by famous thinkers like Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

Heliade also became a government official. He printed official documents, which made him and his family wealthy. However, he still stayed in touch with reform-minded nobles. In 1833, he helped found the Soţietatea Filarmonică (Philharmonic Society). This group promoted culture and raised money for the National Theater. It also secretly worked for political change.

In 1834, when Alexandru II Ghica became Prince, Heliade worked closely with him. He even called himself "court poet." He wrote poems praising Ghica. When young reformers argued with the prince, Heliade tried to stay neutral. He believed that these arguments were just between powerful people, while the peasants suffered. He said, "I hate tyrants. I fear anarchy."

In 1834, Heliade also started teaching at the Philharmonic Society's school. He published his first translations of Lord Byron's poems. He also translated plays by Molière and Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes. His own first collection of writings was printed in 1836. He was also interested in art and opened the first art exhibit in Wallachia in 1837.

By the early 1840s, Heliade believed that modern Romanian needed to connect more with other Romance languages like Italian. He suggested adding new words from Italian. He wrote books like "Parallelism between the Romanian language and Italian" (1840). In 1847, he made a list of Romanian words that came from Slavic, Greek, Turkish, Hungarian, and German languages. He also planned a "universal library" with important philosophical writings.

1848 Revolution

Before Prince Alexandru Ghica was replaced, Heliade's relationship with him became difficult. Heliade then joined a secret society called Frăţia, which opposed the new prince, Gheorghe Bibescu. In 1844, Bibescu leased all Wallachian mines to a Russian engineer, which was seen as illegal. Heliade wrote a pamphlet called Măceșul ("The Eglantine") criticizing Russian influence. It sold over 30,000 copies.

In spring 1848, when revolutions started across Europe, Heliade worked with Frăţia. On April 19, 1848, his newspaper Curierul Românesc stopped printing due to money problems. Heliade became more distant from the most radical groups, especially when they discussed land reform and ending the power of the noble class. However, he initially agreed to some reforms, including national independence, responsible government, civil rights, and freedom of the press.

On June 21, 1848, Heliade read out these goals to a large crowd in Islaz. This was the start of the revolution. Four days later, the revolution successfully removed Prince Bibescu. A Provisional Government was formed, including Heliade, who also became the Minister of Education.

Discussions about land reform continued, but no agreement was reached. Heliade eventually became more conservative about the traditions of the nobles. He believed that the nobles had an important role in Romanian history.

Like most revolutionaries, Heliade wanted to keep good relations with the Ottoman Empire, which was Wallachia's ruler. He hoped this would help against Russian pressure. The Ottoman Sultan sent a general, Süleyman Paşa, to Bucharest. He advised the revolutionaries to continue their diplomatic efforts. The Provisional Government was replaced by a group of three regents called Locotenenţa domnească, which included Heliade. However, the Ottomans were pressured by Russia to stop the revolution. In September, the old system of government was brought back. Heliade sought safety at the British consulate in Bucharest.

Exile

Heliade was allowed to go to the Austrian Empire before moving to France. His wife and children were sent to Ottoman lands. In 1850–1851, he published several books in Paris about the revolution. He lived in Paris with other revolutionaries.

In Paris, he met Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, a philosopher who believed in small-scale property ownership. Heliade used this chance to tell others about the Romanian cause. He also wrote for major French newspapers like La Presse.

Heliade became disappointed with political events. He wrote that Romanians were "idle" and needed "supervision [and] leadership." His money was running out, and he often struggled to pay for basic things. He also argued with other former revolutionaries, like Nicolae Bălcescu, because they disagreed on reforms. Heliade wrote pamphlets criticizing the young radicals.

In 1851, Heliade reunited with his family on the island of Chios. They stayed there until 1854. After Russian troops left the Danubian Principalities during the Crimean War, the Ottoman government asked Heliade to represent Romania in Shumen. He supported the Ottoman cause and was given the title of Bey.

Later that year, he tried to return to Bucharest, but the Austrian authorities, who were controlling the country, made him leave. He went back to Paris and continued to publish books on politics and culture. In 1859, he published his own translation of the Septuagint, which is an old Greek version of the Bible.

When former revolutionaries wanted to unite Wallachia and Moldavia, Heliade did not support any specific candidate. He strongly opposed the former prince, Alexandru II Ghica.

Final years

In 1859, Heliade returned to Bucharest. Bucharest had become the capital of the United Principalities after Alexandru Ioan Cuza was elected. Later, this became the Principality of Romania. Around this time, he added Rădulescu back to his name. Until his death, he published important books on history and literary criticism. In 1863, Prince Cuza gave him a yearly payment.

One year after the Romanian Academy was created, he was chosen as its first President in 1867. He served until he died. In 1869, Heliade helped propose that an Italian diplomat become an honorary member of the Academy. By then, younger writers from a group called Junimea started to criticize Heliade's works.

In the elections of 1866, Heliade Rădulescu became a deputy for Târgovişte. When Prince Cuza was removed from power, Heliade was one of the few Wallachian deputies who opposed bringing in Carol of Hohenzollern as the new ruler. He said that foreign rule was like the old Phanariote period. However, his opposition was not strong enough, and the new ruler was accepted.

Among Ion Heliade Rădulescu's last printed works were a textbook on poetics (1868) and a book on Romanian orthography. Towards the end of his life, he saw himself as a prophet-like figure. He died in his home in Bucharest on April 27, 1872. His funeral was attended by many people who admired him. He was buried in the courtyard of the Mavrogheni Church.

Heliade and the Romanian language

Early ideas for language reform

Heliade's most important work was about developing the modern Romanian language. He combined ideas from the Age of Enlightenment and Romantic nationalism. At a time when educated Romanians often used French or Greek, Heliade and his supporters argued for making Romanian suitable for modern times. He wrote: "Young people, focus on the national language, speak and write in it... The language alone unites, strengthens and defines a nation."

Heliade started suggesting ways to change the language in 1828. He proposed reducing the Cyrillic script to 27 letters, so words would be spelled as they sounded. Soon after, he began to promote adding new words from Romance languages. Romanians in different regions knew they needed to unite the different ways of speaking Romanian. Heliade suggested that the dialect spoken in Muntenia should be the standard language, as it was used in early printed religious texts.

He also had ideas for how Romanian should sound. He said that words of Latin origin should be preferred. He also wanted words to sound good and be used in their most popular form. He also liked shorter, more expressive words. Heliade did not agree with removing foreign words that were already widely used. He believed that trying to remove them would cause more problems than benefits.

These early ideas had a lasting impact. When the Romanian language was unified in the late 1800s, his ideas were used. Mihai Eminescu, a major Romanian poet, praised Heliade for "writing just as [the language] is spoken."

Italian influence on the language

Later, Heliade changed his views on language. By the early 1840s, he thought that Romanian and Italian were not separate languages, but rather different forms of Latin. He then said that Romanian words should be replaced with "better" Italian ones.

This idea was criticized and even made fun of. Eminescu called them "errors." These ideas competed with other systems, like one that used many Latin words and another that used many French words. Some critics said that Heliade's ideas risked "suppressing the Romanian language."

George Călinescu, a literary critic, thought Heliade's experiments came from his dislike of Russia. Heliade wanted to remove Slavic influences from Romanian. Călinescu also believed Heliade's changing ideas came from him teaching himself, which led him to sometimes have "insane theories."

Overall, Heliade's experiments with Italian words were not widely accepted. However, some Italian words he introduced became a permanent part of Romanian, especially for ideas that Romanian didn't have a good word for. Examples include afabil ("friendly"), adorabil ("adorable"), and colosal ("huge").

Literature

Literary style and goals

Heliade is known as the founder of Romanticism in Wallachia. But he was also influenced by Classicism and the Age of Enlightenment. His writing style was a mix of these different ideas. George Călinescu called Heliade "a devourer of books." Heliade loved authors like Alphonse de Lamartine, Dante, Voltaire, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

His poetry was first influenced by Lamartine, then by Classicism, and later returned to Romantic ideas. He believed writers should express their own feelings. He saw writers as "prophets," who should criticize society's problems and look forward to a better future. Heliade also focused on bringing new types of stories and styles to Romanian literature by translating many foreign works.

While some of Heliade's writings are not considered very important today, many others, especially his Romantic poem Zburătorul, are seen as great achievements. Zburătorul uses a character from Romanian mythology—a spirit that visits young girls at night. The poem also shows what a Wallachian village was like at that time.

In an 1837 essay, Heliade gave advice to young writers: "This is not the time for criticism, children, it is the time for writing... create, do not ruin." He meant that writers should focus on creating new works to help Romanian literature grow quickly.

Heliade's name is also strongly linked to the start of Romanian-language theater. He was involved in almost all major developments in local plays and opera. He believed plays should teach lessons and supported professional acting.

Historical and religious themes

Ion Heliade Rădulescu often used Romantic nationalist ideas about history in his poetry. He wanted to educate his readers. He wrote that people should use the great deeds of their ancestors as a model. The main historical figure in his poetry is Michael the Brave, a Wallachian Prince from the late 1500s. Michael was the first to unite Wallachia, Moldavia, and Transylvania. Heliade celebrated him in his poem O noapte pe ruinele Târgoviştii ("A Night on the Ruins of Târgovişte"). He also planned a long poem about Michael, but only finished two parts. Other historical poems also promoted the idea of a single Romanian state.

In the 1860s, Heliade studied Romanian history, especially the origin of the Romanians and the early medieval history of the Danubian Principalities. He believed that the boyars (nobles) had always been an equal and open class. He claimed they had fair laws that were similar to those of the French Revolution.

He also worked on his own ideas about the philosophy of history, based on his understanding of the Bible. His 1858 work, Biblice ("Biblical Writings"), was meant to be the first part of a Christian history of the world. He was interested in the Talmud and mystical numbers like 3, 7, and 10. Some of Heliade Rădulescu's poems also use religious themes.

Satire and arguments

Heliade knew that his work often received negative responses. He was a well-known writer of satire, which he used to criticize society and to talk about his own conflicts. He attacked politicians from different groups. He criticized conservatives who pretended to be liberal. After 1848, he also made fun of radical liberals.

His writings about his own life also showed some self-irony. He often argued with other writers. In one pamphlet, Domnul Sarsailă autorul ("Mr. Old Nick, the Author"), he attacked writers he thought were not very good but pretended to be. In other short stories, he made fun of new rich people in Bucharest.

In his articles, he criticized social trends. In the 1830s, he spoke out against misogyny (dislike of women) and supported women's rights. In 1859, after a pogrom (violent attack) against the Jewish community in Galaţi, he spoke out against Antisemitic accusations. He said, "Jews do not eat children in England, nor do they in France... Where else are they accused of such an inhumane deed? Wherever peoples are still Barbaric or semi-Barbaric."

Many of Heliade's satirical works made fun of how people spoke or their physical features. He mimicked the strict Latin way of speaking of Transylvanian teachers. He also criticized C. A. Rosetti's bulging eyes.

|

See also

In Spanish: Ion Heliade-Rădulescu para niños

In Spanish: Ion Heliade-Rădulescu para niños