Istrian–Dalmatian exodus facts for kids

A young Italian exile on the run carries, along with her personal effects, a flag of Italy (1945)

|

|

| Date | 1943–1960 |

|---|---|

| Location | |

| Cause | The Treaty of Peace with Italy, signed after the Second World War, assigned the former Italian territories of Istria, Kvarner, the Julian March, and Dalmatia to the nation of Yugoslavia |

| Participants | Local ethnic Italians (Istrian Italians and Dalmatian Italians), as well as ethnic Slovenes, Croats, and Istro-Romanians who chose to maintain Italian citizenship. |

| Outcome | Between 230,000 and 350,000 people emigrated from Yugoslavia to Italy and, in a smaller number, towards the Americas, Australia and South Africa. |

The Istrian–Dalmatian exodus was a large movement of people after World War II. Many local ethnic Italians left their homes. They moved from areas that became part of Yugoslavia. These areas included Istria, Kvarner, the Julian March, and Dalmatia.

People who left were mostly Italians. But some were ethnic Slovenes, Croats, and Istro-Romanians. They chose to keep their Italian citizenship. Most of them went to Italy. Others joined the Italian diaspora in places like the Americas, Australia, and South Africa.

These regions had a mix of different groups for a long time. There were Croatian, Italian, and Slovene communities. After World War I, the Kingdom of Italy took control of Istria, Kvarner, the Julian March, and parts of Dalmatia. This included the city of Zadar.

At the end of World War II, a peace treaty was signed. It gave these former Italian lands to Yugoslavia. Only the Province of Trieste remained Italian. Today, these areas are part of Croatia and Slovenia.

Historians believe that between 230,000 and 350,000 people left. This included Italians and others who wanted to stay Italian citizens. The exodus began in 1943 and finished around 1960. Today, only about 21,894 Italians remain in what was once Yugoslavia.

During the first years of the exodus, many local Italians were killed. This happened during World War II. It was done by Yugoslav Partisans and OZNA. These events are known as the foibe massacres. After 1947, Yugoslav authorities used other ways to make people leave. They took over properties and charged high taxes. This left many Italians with no choice but to move.

Overview of the exodus

People who spoke Romance languages have lived in Istria for a very long time. This was true since the fall of the Roman Empire. Cities along the coast had many Italian people. They traded with other areas. But the inland areas were mostly Slavic, especially Croatian.

For centuries, Istrian Italians made up more than half of the population. By 1900, they were about a third. In 1910, an Austrian census showed that out of 404,309 people in Istria, 36.5% spoke Italian. The rest spoke Croatian, Slovene, German, or other languages.

A new group of Italians arrived between 1918 and 1943. These were not the native Italian speakers. At that time, parts of Slovenia and Croatia were considered part of Italy. A 1936 Italian census showed about 230,000 people spoke Italian there.

From the end of World War II until 1953, many people left these regions. Estimates say between 250,000 and 350,000 people moved. Before the war, about 225,000 Italians lived there. So, many Slovenes and Croats also left. They were against the Communist government in Yugoslavia.

About two-thirds of those who left were local ethnic Italians. They had lived there permanently before the war. They wanted to become Italian citizens and move to Italy. In Yugoslavia, they were called optanti (meaning 'choosers'). In Italy, they were known as esuli (meaning 'exiles'). This emigration greatly changed the population of the region.

By 1953, only 36,000 Italians remained in Yugoslavia. This was only 16% of the number before World War II.

History

Early history

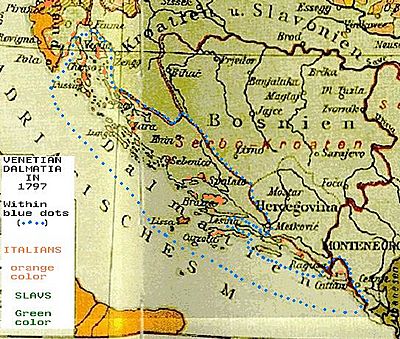

The Republic of Venice expanded its control to coastal parts of Istria and Dalmatia. This happened between the 9th century and 1797. Venice attacked Zadar many times. In 1202, Venice used crusaders to attack and rob the city. The Pope was angry and excommunicated them. Venice also attacked the Republic of Ragusa and Constantinople.

Coastal cities in Istria came under Venetian influence in the 9th century. By 1267, Poreč was part of Venice. Other towns followed. Venice gradually controlled the western coast of Istria. Dalmatia was sold to Venice in 1409.

From the Middle Ages, more Slavic people moved to the Adriatic coast. This was due to their growing population. Also, the Ottomans pushed them from the south and east. This meant Italian people mostly lived in cities. The countryside was settled by Slavs. The population was divided into city dwellers (Romance speakers) and rural people (Slavic speakers).

The Republic of Venice influenced the Italian speakers of Istria and Dalmatia. This lasted until 1797, when Napoleon conquered it. Cities like Capodistria and Pola were important art centers. For centuries, Italian and Slavic communities lived peacefully. They saw themselves as "Istrians" or "Dalmatians." They identified by their culture, either "Romance" or "Slavic."

Austrian Empire

After Napoleon's defeat in 1814, Istria, Kvarner, and Dalmatia became part of the Austrian Empire. Many Istrian and Dalmatian Italians supported the Risorgimento movement. This movement wanted to unite Italy.

However, after 1866, Veneto and Friuli joined Italy. But Istria and Dalmatia stayed with the Austro-Hungarian Empire. This led to Italian irredentism. Many Italians in these areas wanted to join Italy. The Austrians saw Italians as enemies. They favored the Slavic communities instead.

In 1866, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria ordered actions against Italian influence. He wanted to promote Germanization or Slavization. This meant encouraging German or Slavic culture and language. He wanted to do this in areas with Italian populations.

Istrian Italians were a majority for centuries. But by 1900, they were about a third of the population. In Dalmatia, Italians were 33% in 1803. This dropped to 20% by 1816. By 1910, only 2.8% of Dalmatia's population spoke Italian. In 1909, Italian stopped being an official language in Dalmatia. Only Croatian was recognized.

World War I and post-War period

In 1915, Italy joined World War I against Austria-Hungary. This led to fierce fighting. Britain, France, and Russia wanted Italy to join them. Italy demanded new territories if they won the war.

Under the London Pact, Italy would get Italian-speaking areas like Trentino and Trieste. They would also get German-speaking South Tyrol. And they would get Istria and northern Dalmatia, including Zadar. The city of Fiume (Rijeka) was not included.

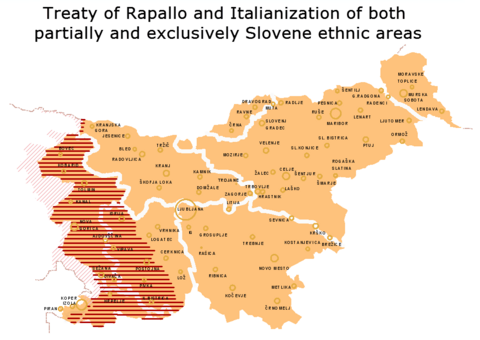

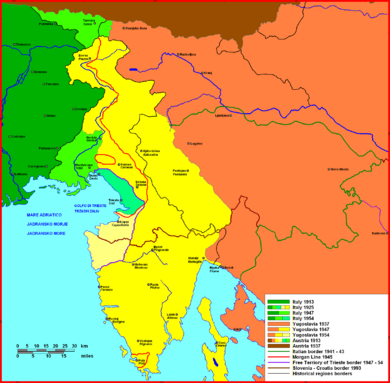

After the war, the Treaty of Rapallo was signed in 1920. Italy gained Zadar, some islands, and most of Istria. This included Trieste. The rest went to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (later Yugoslavia). In 1924, the Treaty of Rome divided the city of Fiume.

Between 1910 and 1921, Istria lost 15.1% of its population. This was due to World War I and political changes. Many people also moved away. For example, Pula was badly affected. Its large Austrian military presence left. This caused economic problems. Thousands of Croat farmers moved to Yugoslavia.

About 30,000 Istrians moved between 1918 and 1921. Most were Austrians, Hungarians, and Slavs. They had worked for the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Slavs under Italian Fascist rule

After World War I, Italy gained most of Istria and Trieste. This was under the Treaty of Rapallo in 1920. Later, in 1924, Italy also took Rijeka.

In these areas, Italy started a policy of Italianization. This meant forcing people to use the Italian language and culture. This happened in the 1920s and 1930s. Fascist violence also occurred. For example, the Narodni dom (National House) in Pula and Trieste was burned down. This happened in 1920.

The situation worsened after Benito Mussolini came to power in 1922. In 1923, Croatian and Slovene languages were banned in government. Their use in courts was forbidden in 1925. Croatian and Slovenian groups were also banned. All their activities had to stop by 1927.

At the same time, Yugoslavia tried to force Croatisation. This was against the Italian minority in Dalmatia. Most Italian Dalmatians decided to move to Italy.

World War II

In April 1941, Germany invaded Yugoslavia. Italy then expanded its occupied zone. Italy took large parts of Croatia and Slovenia. This included the capital, Ljubljana.

Italian forces, helped by the Ustaše (a Croatian fascist group), fought against Yugoslav Partisans. They also imprisoned thousands of Yugoslav civilians. This made anti-Italian feelings grow stronger.

Italian occupation continued until September 1943. During this time, the population faced harsh treatment. This often happened with the help of the Ustaše.

After World War II, many people chose to leave Yugoslavia. They preferred Italy over living under communist rule. In Yugoslavia, they were called optanti (choosers). They called themselves esuli (exiles). They left because they feared revenge. They also faced economic and ethnic problems.

Events of 1943

When the Fascist government fell in 1943, there were attacks against Italian fascists. Josip Broz Tito's resistance movement killed several hundred Italians in September 1943. Some were linked to the fascist government. Others were victims of personal grudges. The Partisans also wanted to remove anyone they thought was an enemy.

The Foibe massacres

Between 1943 and 1947, a wave of violence happened. It was known as the "Foibe massacres". This was mainly done by OZNA and Yugoslav Partisans. It happened in the Julian March (Karst Region and Istria), Kvarner, and Dalmatia.

The victims were mostly local ethnic Italians. But it also included anti-communists in general. This included Croats and Slovenes. They were often linked to Fascism or Nazism. Or they were seen as opponents of Tito's communism. The attacks included revenge killings and ethnic cleansing against Italians.

A special Italian-Slovenian Historical Commission was set up in 1995. It investigated these events. The commission said the killings were partly revenge against fascists. But they also seemed to be part of a plan. This plan was to remove anyone linked to Fascism or the Italian state. It also aimed to remove anyone who might oppose the new communist government.

The Yugoslav partisans wanted to kill anyone who might stop them from taking over Italian lands. They also targeted anti-fascist leaders. For example, in the city of Fiume, at least 650 people were killed. This happened after Yugoslav units arrived.

The term "foibe" refers to deep natural sinkholes. Victims were often thrown into these holes, sometimes alive. The number of people killed in the foibe is debated. Estimates range from hundreds to thousands. Some sources say 11,000 or 20,000. These massacres were followed by the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus.

The exodus

Many factors led to the exodus. These included economic problems, ethnic tensions, and the political situation. Up to 350,000 people left Istria, Dalmatia, and the northern Julian March. Most of them were Italians.

The exiles were promised money for their lost property. But they often did not receive anything. They had fled difficult conditions. They were then housed in former concentration camps or prisons. Some Italians also treated them badly. They saw the exiles as taking scarce food and jobs. After the exodus, Yugoslav people settled in these areas.

In 1991, a Yugoslav political figure named Milovan Đilas spoke about the exodus. He said he was sent to Istria in 1946. His job was to create anti-Italian propaganda. He stated it was "necessary to employ all kinds of pressure to persuade Italians to leave." This was because Italians were a majority in the cities.

During 1946 and 1947, there was also a "counter-exodus." Hundreds of Italian Communist workers moved to Yugoslavia. They went to places like the shipyards of Rijeka. They took the places of the Italians who had left. They believed Yugoslavia was building socialism. But they were soon disappointed. The Yugoslav government accused them of disloyalty. Some were sent to concentration camps.

The Italian bishop of Poreč and Pula, Raffaele Radossi, was replaced in 1947. He later moved to Pula, which was under Allied control. He faced threats and attacks. The Bishop of Rijeka also left for Italy in 1947.

Periods of the exodus

The exodus happened between 1943 and 1960. The main movements of people took place in these years:

- 1943

- 1945

- 1947

- 1954

The first period began after Italy surrendered in the war. This led to the first wave of anti-fascist violence. The German army was retreating from the Yugoslav Partisans.

The city of Zadar saw a huge departure of Italians. Between November 1943 and 1944, Zadar was bombed by the Allies. Many civilians died. Many old buildings and artworks were destroyed. A large number of people fled the city. By the end of 1944, Zadar's population dropped from 24,000 to 6,000.

A second wave of people left at the end of the war. This was due to killings and property seizures. Yugoslav authorities put pressure on people to leave.

On May 2–3, 1945, the Yugoslav Army occupied Rijeka. More than 500 people were killed there. This included Italian military and public servants. The leaders of the local Autonomist Party were also murdered. By January 1946, over 20,000 people had left the area.

After 1945, other forms of pressure encouraged people to leave. These included taking over properties. Transport services to Trieste were stopped. People working in one zone but living in another faced high taxes. Clergy and teachers were persecuted. Economic problems also pushed people to leave.

The third part of the exodus happened after the Paris peace treaty. Istria was given to Yugoslavia. Only a small part became the independent Free Territory of Trieste. The coastal city of Pula saw a massive exodus of its Italian population. Between December 1946 and September 1947, Pula became almost empty. Its residents left everything to become Italian citizens. Out of 32,000 people, 28,000 left.

The fourth period happened after the Memorandum of Understanding in London. This agreement gave Italy control of Trieste. Yugoslavia got control of another zone. Finally, in 1975, the Treaty of Osimo officially divided the former Free Territory of Trieste.

Estimates of the exodus

Historians have different estimates for the number of people who left:

- Vladimir Žerjavić (Croat): 191,421 Italian exiles from Croatian territory.

- Nevenka Troha (Slovene): 40,000 Italian and 3,000 Slovene exiles from Slovenian territory.

- Raoul Pupo (Italian): About 250,000 Italian exiles.

- Flaminio Rocchi (Italian): About 350,000 Italian exiles.

The Italian-Slovenian Historical Commission confirmed 27,000 Italian and 3,000 Slovene migrants from Slovenian territory. For decades, Yugoslav authorities did not talk about the exodus. But in 1972, Tito himself said that 300,000 Istrians had left after the war.

Famous exiles

Many famous people have families who left Istria or Dalmatia after World War II. Here are some of them:

- Alida Valli, film actress

- Mario Andretti, racing driver

- Lidia Bastianich, chef

- Nino Benvenuti, boxer and Olympic gold medalist

- Enzo Bettiza, novelist and journalist

- Valentino Zeichen, poet and writer

- Laura Antonelli, film actress

- Sergio Endrigo, singer and songwriter

- Antonio Blasevich, soccer player

- Silvio Ballarin, scientist

- Dino Ciani, pianist

- Giovanni Cucelli, tennis player

- Renzo de' Vidovich, politician and journalist

- Aldo Duro, dictionary maker

- Wilma Goich, singer

- Irma Gramatica, actress

- Ezio Loik, soccer player

- Ottavio Missoni, fashion designer

- Anna Maria Mori, writer

- Abdon Pamich, walker

- Pier Antonio Quarantotti Gambini, writer

- Nicolò Rode, sailor

- Orlando Sirola, tennis player

- Agostino Straulino, sailor

- Leo Valiani, politician

- Rodolfo Volk, soccer player

Legacy

Property reparation

In 1983, Yugoslavia and Italy signed a treaty. Yugoslavia agreed to pay $110 million to compensate exiles. This was for property taken after the war in the Free Territory of Trieste's Zone B.

However, this issue is very complex. The exiles have not yet received full compensation. It is unlikely that exiles from outside Zone B will ever be paid. The topic of property compensation is still discussed by the Istrian Democratic Assembly. This is a regional party in Istria.

Minority rights in Yugoslavia

During Yugoslavia's communist period (1945–1991), equality for different ethnic groups was important. In 1943, the federation of Yugoslavia was formed. It promised that "Ethnic minorities in Yugoslavia shall be granted all national rights." These rules were put into the constitutions of 1946, 1963, and 1974.

The 1974 constitution stated that all groups should have equal rights. It said that "each nationality has the sovereign right freely to use its own language and script, to foster its own culture, to set up organizations for this purpose, and to enjoy other constitutionally guaranteed rights."

Day of Remembrance

In Italy, March 30, 2004, Law 92 was passed. It declared February 10 as a Day of Remembrance. This day remembers the victims of the Foibe massacres and the Istrian–Dalmatian exodus. The law also created a special medal for the victims' families: ![]() Medal of Day of Remembrance to relatives of victims of foibe killings

Medal of Day of Remembrance to relatives of victims of foibe killings

The remaining Italians

In 2001 (Croatia) and 2002 (Slovenia), censuses were taken. They showed that 21,894 Italians remained in former Yugoslavia. This included 2,258 in Slovenia and 19,636 in Croatia. More people speak Italian as a second language.

After Yugoslavia broke up, many people in Istria chose to identify as "Istrians" in the census. This means more people speak Italian as their first language than those who identify as Italian.

The number of people in Croatia who said they were Italian almost doubled between 1981 and 1991. The main newspaper for Italians in Croatia, La Voce del Popolo, is published in Rijeka.

Official bilingualism

Italian is an official language alongside Slovene in four towns in Slovenian Istria. These are Piran (Pirano), Koper (Capodistria), Izola (Isola d'Istria), and Ankaran (Ancarano). In many towns in Croatian Istria, Italian is also an official language.

The city of Rijeka also supports the use of Italian. It ensures the Italian minority can use their language in public affairs. It also supports their education and cultural activities.

In Croatian Istria, some towns have many Italian speakers. For example, 51% of people in Grožnjan/Grisignana speak Italian. In Brtonigla/Verteneglio, it's 37%. In Buje/Buie, it's nearly 30%. Italian is co-official with Croatian in nineteen municipalities in Croatian Istria.

Education and Italian language

Slovenia

Besides Slovene schools, there are also kindergartens and schools with Italian as the teaching language. These are in Koper/Capodistria, Izola/Isola, and Piran/Pirano. However, at the University of Primorska, Slovene is the only teaching language.

Croatia

In Istria, there are kindergartens and primary schools with Italian as the teaching language. These are in many towns like Buje/Buie, Pula/Pola, and Rovinj/Rovigno. There are also lower and upper secondary schools in Buje/Buie, Rovinj/Rovigno, and Pula/Pola.

The city of Rijeka/Fiume has Italian kindergartens and elementary schools. There is also an Italian Secondary School in Rijeka. The town of Mali Lošinj/Lussinpiccolo has an Italian kindergarten.

In Zadar, in the Dalmatia region, Italians asked for an Italian kindergarten. It opened in 2013, hosting 25 children. This was the first Italian school in Dalmatia since 1953. Since 2017, a Croatian primary school offers Italian language classes. Italian courses are also available in a secondary school and at the university.

See also

In Spanish: Éxodo istriano-dálmata para niños

In Spanish: Éxodo istriano-dálmata para niños

- Foibe massacres

- National Memorial Day of the Exiles and Foibe

- Free Territory of Trieste

- World War II in Yugoslavia

- Italian Social Republic

- Istria

- Italian language in Croatia

- Italian language in Slovenia

- Dalmatia

- Italianization

- Croatisation

- Flight and expulsion of Germans (1944–50)

- Ethnic cleansing in the Bosnian War

- Niçard exodus

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |