Libyan civil war (2011) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids First Libyan Civil War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Arab Spring and Libyan Crisis since 2011 | |||||||

From left to right: Armed pro-government supporters; Pro-government protesters gathered in Green Square, now known as Martyrs' Square; anti-Government protesters in Benghazi; Libyan rebels on a captured T-55 tank. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

NATO members

Other countries

Minor border clashes: |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

|||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

200,000 volunteers by war's end International Forces: Numerous air and maritime forces (see here) |

20,000–50,000 soldiers & militiamen | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 5,904–6,626 killed (other estimates: see here) |

3,309–4,227 soldiers killed (other estimates: see here) |

||||||

| Total casualties (including civilians): 30,000+ killed 4,000 missing 50,000 wounded 7,000 captured (other estimates: see here) |

|||||||

| *Large number of loyalist or immigrant civilians, not military personnel, among those captured by rebels, only an estimated minimum of 1,692+ confirmed as soldiers | |||||||

The First Libyan Civil War was a big fight in 2011 in the North African country of Libya. It was between forces loyal to Colonel Muammar Gaddafi and rebel groups who wanted to remove his government. The war started with protests in Benghazi on 15 February 2011. These protests quickly grew into clashes with security forces.

The protests turned into a rebellion that spread across Libya. The groups against Gaddafi formed a temporary government called the National Transitional Council. The United Nations Security Council stepped in on 26 February. They froze Gaddafi's money and stopped him and his close friends from traveling.

In March, Gaddafi's forces fought back and took over several cities. The UN then allowed countries to create a "no-fly zone" over Libya. This meant no planes could fly there, to protect civilians from attacks. This led to NATO forces bombing Libyan military sites. Gaddafi's government said they would stop fighting, but the battles and bombings continued. The rebels refused any peace offers that did not include Gaddafi leaving power.

In August, rebel forces, with NATO's help, attacked the coast of Libya. They took back land and eventually captured the capital city of Tripoli. Gaddafi managed to escape capture for a while. On 16 September 2011, the United Nations recognized the National Transitional Council as Libya's official government. Muammar Gaddafi was found and killed in Sirte on 20 October 2011. The National Transitional Council declared Libya "liberated" on 23 October 2011, officially ending the war.

After the war, there were still small fights from Gaddafi's supporters. Different local groups and tribes also had disagreements. These problems eventually led to a second civil war in Libya in 2014.

Contents

Libya Before the War

Gaddafi's Leadership

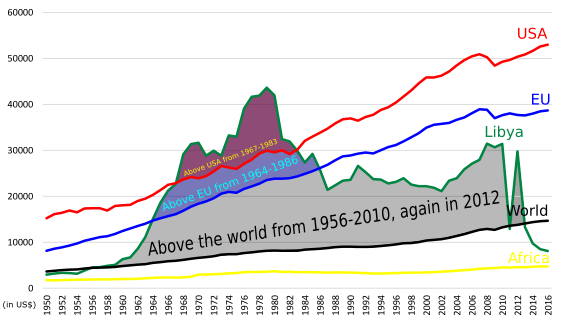

Muammar Gaddafi became the leader of Libya in 1969. He led a group of Arab nationalists who removed King Idris I without a fight. Gaddafi got rid of the old constitution. From 1969 to 1975, life in Libya improved a lot. People lived longer, more people could read, and their living standards went up.

In 1977, Gaddafi officially stepped down from power. He said he was just a "symbolic figurehead" after that. Libya was supposed to be a direct democracy, where people ruled through local committees. However, many believed Gaddafi still controlled everything. He kept his family and loyal tribe members in important military and government jobs. This helped him stay in power for a long time.

Gaddafi was thought to be worried about a military takeover. So, he kept Libya's army quite weak. The most powerful army units were four special brigades. These were made up of soldiers from Gaddafi's tribe or other loyal tribes. One of these was led by his son, Khamis. Regular army units were not as well trained or equipped.

Economy and Daily Life

By the end of Gaddafi's 42-year rule, Libya had a good income per person. However, about a third of the people still lived in poverty. Gaddafi's government banned Child marriage. Women gained equal pay and rights in divorce. More women also went to college. Homelessness was very low, and most people could read.

Most of Libya's money came from its oil production. This money was used for many things, including buying weapons and supporting groups around the world. Libya was one of the world's largest oil producers. Before the war, it produced about 1.6 million barrels of oil every day.

Libya also had a large national savings fund, worth about US$56 billion. This included over 100 tons of gold. Libya's living standards, education, and health were better than in nearby Egypt and Tunisia. These countries also had their own "Arab Spring" protests.

However, there were problems. Libya was seen as a very corrupt country. Many businesses were controlled by Gaddafi, his family, or close friends. His relatives lived very fancy lives. Gaddafi himself said he wanted to fight corruption. He suggested giving oil money directly to the people instead of through government bodies. This plan was delayed after a national vote in 2009.

Human Rights in Libya

Libya was known for having very strict control over the media. In 2009 and 2011, it was rated as one of the most censored countries in the Middle East and North Africa. However, a UN report in January 2011 praised some parts of Libya's human rights record. This included how women were treated.

The Libyan government said that its system allowed all citizens to have a say in political matters. They also claimed that no one in Libya suffered from extreme poverty or hunger. They said the government provided basic needs and financial help for housing.

However, there were also reports of tight control over people who disagreed with the government. Some people worked as informants, watching others in government, factories, and schools. People who spoke out against the government could face harsh punishments.

The Anti-Gaddafi Movement

Start of Protests

In January 2011, people in cities like Bayda, Derna, and Benghazi protested. They were upset about delays in building homes and about government corruption. They broke into and took over houses the government was building. Protesters also clashed with police and attacked government offices. The government responded by promising a large investment fund for housing.

A writer named Jamal al-Hajji called for protests on the internet. He was inspired by similar revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt. He was arrested in February. Gaddafi warned activists and journalists that they would be responsible if they caused trouble.

These protests led to the uprising and civil war, as part of the bigger Arab Spring movement. Social media played a big part in organizing the opposition.

Uprising and Civil War Begin

The protests started seriously on 2 February 2011. They were called the Libyan Revolution of Dignity. In Zawiya, foreign workers and unhappy minority groups protested. On 15 February, hundreds of people protested in Benghazi after a human rights lawyer was arrested. Crowds threw stones and Molotov cocktails. Police used tear gas and rubber bullets. Many people were injured.

On 16 February, protesters in Bayda, Zawiya, and Zintan set fire to police and security buildings. A "Day of Rage" was planned for 17 February. Protests happened in many cities, and security forces fired live ammunition. Protesters burned government buildings. In Tripoli, TV stations and government offices were attacked.

On 18 February, police and army left Benghazi because there were too many protesters. Some army members even joined the protesters. In Bayda, reports said police joined the protesters too.

Cultural Protest

Music, especially Rap and hip hop, helped encourage people to protest against Gaddafi's government. Music was a way for protesters to communicate and feel supported.

An anonymous hip hop artist called Ibn Thabit used his music to speak for Libyans who felt powerless. He had been criticizing Gaddafi since 2008. His songs talked about the rebel feelings even before the riots began. Other groups used metaphors in their songs to criticize the authorities without being too obvious.

Organizing the Opposition

Many opposition members wanted to go back to the 1952 constitution. They wanted a multi-party democracy, where different political groups could exist. Army units that joined the rebellion and many volunteers formed fighting groups. They defended against Gaddafi's attacks and tried to take control of Tripoli.

The National Transitional Council (NTC) was formed on 27 February. Its main goals were to organize the resistance in rebel-held towns and represent the opposition to the world. They did not plan to form a temporary government at first. The NTC called for a no-fly zone and airstrikes against Gaddafi's forces. They started calling themselves the Libyan Republic.

An independent newspaper called Libya appeared in Benghazi. Rebel-controlled radio stations also started broadcasting. Some rebels were against tribalism and wore clothes saying "No to tribalism."

Who Were the Rebels?

The rebels were mostly ordinary people. This included teachers, students, lawyers, and oil workers. Some police officers and professional soldiers also joined them. Many Islamists were part of the rebel movement.

Gaddafi's government often said that the rebels included al-Qaeda fighters. The rebels denied this. NATO leaders said there were "flickers" of al-Qaeda activity but not enough to confirm a large presence. However, some past reports suggested that Libya had provided many foreign fighters to al-Qaeda.

Responses Inside Libya

Government Officials Resign

Many high-ranking Libyan officials left Gaddafi's government or resigned. This was because of the violence used against protesters. The Justice Minister and Interior Minister both joined the opposition. The Oil Minister and Foreign Minister fled Libya. Many Libyan diplomats around the world also resigned or spoke out against Gaddafi.

Military Members Join Rebels

Several senior military officers joined the opposition. Two Libyan Air Force colonels flew their fighter jets to Malta and asked for safety. They had been ordered to bomb civilians in Benghazi. The commander of the Benghazi Naval Base also joined the rebels.

The Royal Family's View

Muhammad as-Senussi, a relative of the former King of Libya, sent his sympathy to those killed by Gaddafi's forces. He asked the international community to stop supporting Gaddafi. He also called for a no-fly zone over Libya but did not want foreign ground troops. He said he would support any government Libya chose after Gaddafi.

The War's Progress

First Weeks of Fighting

By 23 February, Gaddafi was losing support. Many allies resigned, and he lost control of major cities like Benghazi and Misrata. He also lost important harbors. However, in early March, Gaddafi's forces fought back. They pushed the rebels away and reached Benghazi and Misrata again.

Foreign Military Steps In

On 19 March 2011, a group of countries started military action in Libya. They were following a UN resolution to protect civilians. US and British forces fired missiles. Air forces from Canada, France, the US, and the UK flew missions over Libya. The British navy also created a naval blockade.

The group of countries grew to 17 states. Most of these countries helped enforce the no-fly zone and naval blockade. They also provided military support. NATO took control of the arms embargo on 23 March. This was called Operation Unified Protector.

In May 2011, Russia recognized the National Transitional Council (NTC) as a legal group to talk with. In June 2011, Muammar Gaddafi and his son, Saif al-Islam, said they would hold elections. Gaddafi said he would step down if he lost. NATO and the rebels rejected this offer and continued their attacks.

Some reports later suggested that NATO's actions went beyond just protecting civilians. They seemed to be helping the rebels advance.

Rebels Attack Tripoli

On 21 August, rebel leaders said Gaddafi's son, Saif al-Islam, was arrested. They also said they had surrounded Gaddafi's compound. This suggested the war was almost over. By 22 August, rebel fighters entered Tripoli and took over Green Square. They quickly renamed it Martyrs' Square.

On 23 August, rebels broke into Gaddafi's Bab al-Azizia compound in Tripoli. No members of Gaddafi's family were found there. Gaddafi later said his withdrawal from the compound was a "tactical" move. Rebels estimated that 400 people were killed and 2,000 injured in the battle for Tripoli.

After Tripoli and Rebel Victory

After taking Tripoli, rebels worked to clear out Gaddafi's forces in other areas. They captured the city of Ghadames on 29 August. Members of Gaddafi's family fled to Algeria. In September, rebels surrounded Bani Walid, where Gaddafi's son Saif al-Islam was believed to be hiding. On 22 September, the NTC captured the southern city of Sabha.

By mid-October 2011, NTC forces had taken most of Sirte. Heavy fighting continued in the city center. The NTC captured all of Sirte on 20 October 2011. They also reported that Gaddafi himself had been killed in the city.

On 1 September, Russia recognized the Libyan NTC as the only legal government. China also recognized the NTC on 12 September.

Aftermath of the War

Even after Gaddafi's defeat and death, his son Saif al-Islam remained hidden until his capture in November. Some loyalist forces also tried to escape into Niger. Small clashes between the NTC and former loyalists continued in Libya.

By September 2013, Libya was facing a very difficult time. Oil production had almost stopped. The government had lost control of large parts of the country to different armed groups. Violence increased across Libya. By May 2014, these conflicts led to a second civil war.

Impact of the War

Casualties

It is hard to know the exact number of people killed and injured in the war. Estimates have varied a lot.

- On 24 February, Gaddafi's government said about 300 people were killed.

- The International Criminal Court estimated 10,000 deaths.

- By 22 February, about 4,000 people were estimated to be injured.

- Later, a rebel spokesman said 8,000 people had died.

- One database listed 6,109 deaths from 15 February to 23 October 2011.

Humanitarian Situation

By the end of February 2011, cities in Libya were running low on medicine, fuel, and food. The International Committee of the Red Cross asked for US$6.4 million to help people affected by the violence. By early March, over a million people needed humanitarian aid.

Many people also became refugees, fleeing the crisis. A ship helped evacuate stranded migrants from Misrata. By 10 July, over 150,000 migrants were evacuated. Thousands of refugees crossed the border into Tunisia and Egypt daily. These included Libyans and foreign workers.

Libyan Refugees

Many people fled the violence in Tripoli by road. As many as 4,000 refugees crossed the Libya–Tunisia border each day in the early days of the uprising. By 1 March, officials confirmed that sub-Saharan Africans were being treated unfairly at the border. By 3 March, about 200,000 refugees had fled to Tunisia or Egypt. Refugee camps became very crowded.

In September, it was reported that almost all the people from Tawergha, a town of about 10,000, were forced to leave their homes by anti-Gaddafi fighters. This was possibly due to racism and anger from fighters in Misrata because Tawergha had supported Gaddafi.

Economic and Tribal Impacts

Oil prices around the world went up during the conflict because Libya has a lot of oil. The second-largest state-owned oil company in Libya said it would use oil money to support the anti-Gaddafi forces. Islamic leaders in Libya also urged Muslims to rebel against Gaddafi.

Some tribes, like the Magarha, supported the protesters. The Zuwayya tribe threatened to stop oil exports if security forces kept attacking protesters.

The Tuareg people consistently supported Gaddafi during the Civil War. Gaddafi had given many Tuareg people safety from harm in other countries. He also supported their culture. Because of this, many Tuareg fighters were ready to "fight for Gaddafi to the last drop of blood." Tuareg areas like Ghat are still loyal to Gaddafi today.

International Reactions

Many countries and international groups spoke out against Gaddafi's government. They were concerned about reports of air attacks on civilians. Most Western countries stopped diplomatic relations with Gaddafi's government.

The United Nations Security Council Resolution 1970 was passed on 26 February. It froze Gaddafi's money and limited his travel. It also asked the International Criminal Court to investigate. An arrest warrant for Gaddafi was issued on 27 June.

Later, United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973 was passed on 17 March. This created a Libyan no-fly zone. Countries involved in enforcing this zone also carried out airstrikes. These strikes aimed to weaken the Libyan Army and destroy the government's ability to control its forces. This effectively helped the anti-Gaddafi forces on the ground.

China and Russia, who had not voted against the resolution, later said that the "no-fly zone" had gone too far beyond its original goals.

One hundred countries recognized the anti-Gaddafi National Transitional Council as Libya's rightful representative. Many countries saw them as the legal temporary government.

Many countries also advised their citizens not to travel to Libya or tried to evacuate them. Some evacuations were successful, taking people to Malta or across land borders to Egypt or Tunisia. Other attempts were difficult due to airport damage or denied landing permissions. There were also protests in other countries by Libyan people living abroad. The instability in Libya caused oil prices around the world to rise.

Images for kids

-

Graffiti in Benghazi, drawing the connection to the Arab Spring

-

Destroyed tanks in a scrap yard outside Misrata

-

A young Benghazian carrying (deposed) King Idris' photo. Support of the Senussi dynasty has traditionally been strong in Cyrenaica.

-

Loyalist Palmaria howitzers destroyed by the French air force near Benghazi in Opération Harmattan on 19 March 2011

-

President Barack Obama speaking on the military intervention in Libya at the National Defense University.

-

A total of 19 charter flights evacuated Chinese citizens from Libya via Malta. Here a chartered China Eastern Airlines Airbus A340 is seen at Malta International Airport on 26 February 2011.

See also

In Spanish: Guerra de Libia de 2011 para niños

In Spanish: Guerra de Libia de 2011 para niños

- 1976 Libyan protests

- 2011 Battle of Tripoli

- 2011 Battle of Sirte

- Aftermath of the First Libyan Civil War

- Arab Spring

- Free speech in the media during the 2011 Libyan Civil War

- Moussa Ibrahim, Gaddafi's spokesman

- Human rights in Libya

- List of modern conflicts in North Africa

- List of modern conflicts in the Middle East

- Green Resistance

- 2015 European migrant crisis

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |