Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Most Honourable

The Marquess of Salisbury

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

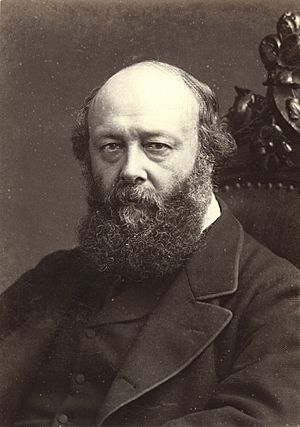

Lord Salisbury c. 1886

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 25 June 1895 – 11 July 1902 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | The Earl of Rosebery | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Arthur Balfour | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 25 July 1886 – 11 August 1892 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | Victoria | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | William Ewart Gladstone | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | William Ewart Gladstone | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 23 June 1885 – 28 January 1886 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | Victoria | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | William Ewart Gladstone | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | William Ewart Gladstone | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil

3 February 1830 Hatfield, Hertfordshire, England |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 22 August 1903 (aged 73) Hatfield, Hertfordshire, England |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | St Etheldreda's Church, Hatfield | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Conservative | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parents |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Christ Church, Oxford | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cabinet | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (born February 3, 1830 – died August 22, 1903), often called Lord Salisbury, was an important British politician. He was a member of the Conservative Party. He served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom three times, for more than thirteen years in total. He was also the Foreign Secretary, managing Britain's relationships with other countries, for most of his time as Prime Minister. He believed in a policy called "splendid isolation", which meant avoiding strong alliances with other nations.

Lord Salisbury was first elected to the House of Commons in 1854. He became Secretary of State for India in 1866. Later, in 1878, he became Foreign Secretary and played a big part in the Congress of Berlin, a meeting where European countries discussed how to deal with the Ottoman Empire. After another leader, Benjamin Disraeli, died in 1881, Lord Salisbury became the main leader of the Conservative Party in the House of Lords.

He became Prime Minister for the first time in June 1885. When William Ewart Gladstone suggested "Home Rule" for Ireland (meaning Ireland would govern itself more), Lord Salisbury was against it. He teamed up with a group called the Liberal Unionists and won the next election in 1886. During this time, he helped Britain gain a lot of new land in Africa without going to war. He served as Prime Minister again from 1886 to 1892.

He became Prime Minister for the third and last time in 1895. He led Britain to victory in the Second Boer War and won another election in 1900. He stepped down as Prime Minister in 1902 and passed away in 1903. He was the last Prime Minister to serve while being a member of the House of Lords. Historians see him as a strong leader, especially in foreign affairs.

Contents

- Early Life and Education: 1830–1852

- Becoming a Member of Parliament: 1853–1866

- Serving as Secretary of State for India: 1866–1867

- In Opposition and New Roles: 1868–1874

- Return as Secretary of State for India: 1874–1878

- Foreign Secretary: 1878–1880

- Leader of the Opposition: 1881–1885

- First Time as Prime Minister: 1885–1886

- Second Time as Prime Minister: 1886–1892

- Leader of the Opposition Again: 1892–1895

- Third Time as Prime Minister: 1895–1902

- Last Year and Legacy: 1902–1903

- Family Life

- Cabinets of Lord Salisbury

- See also

Early Life and Education: 1830–1852

Robert Cecil was born at Hatfield House. He was the third son of the 2nd Marquess of Salisbury. His family was very wealthy and owned large estates. His family's wealth grew even more when his father married Frances Mary Gascoyne, who was also very rich.

Robert had a difficult childhood. He had few friends and spent most of his time reading. He was bullied a lot at school. He went to Eton College in 1840 but left in 1845 because of the bullying. This difficult time made him feel quite negative about life and about democracy. He thought that many people were unkind and that large groups could be unfair to individuals.

In 1847, he went to Christ Church, Oxford university. He studied mathematics there. He also became very interested in a religious movement called the Oxford Movement. In 1853, he became a fellow at All Souls College, Oxford.

From 1851 to 1853, Robert Cecil traveled for his health. He visited places like Cape Colony (in South Africa), Australia, and New Zealand. He wrote about his travels, sharing his thoughts on the people and places he saw. For example, he noted that the Māori of New Zealand seemed to be "much better Christians than the white man" after converting.

Becoming a Member of Parliament: 1853–1866

Robert Cecil became a MP for Stamford in Lincolnshire on August 22, 1853. He was a member of the Conservative Party. He kept this seat until 1868 when he became a Marquess after his father's death.

He also started writing articles for newspapers and journals, often without his name on them. He wrote for the Saturday Review and the Quarterly Review. He used his writing to share his political ideas and criticize the government's foreign policy. He believed Britain should not threaten other countries unless it was ready to use force.

Serving as Secretary of State for India: 1866–1867

In 1866, Robert Cecil, now known as Viscount Cranborne, joined the government as Secretary of State for India. This role meant he was in charge of British India.

He spoke out strongly against how the government handled the Orissa famine in India. He said that many people died because officials were more worried about wasting money than saving lives. This event made him distrust experts and government officials for the rest of his life.

Changes to Voting Laws: The Reform Act of 1867

In the mid-1860s, there was a big debate about changing who could vote in Britain. This was called parliamentary reform. Cranborne studied the voting numbers very carefully. He wanted to make sure that any new law would not harm the Conservative Party.

He was very surprised when Benjamin Disraeli, another Conservative leader, decided to support a much bigger change to voting rights than expected. Cranborne and some other ministers resigned from the government because they disagreed with Disraeli's plan. Cranborne believed that Disraeli's plan would give too much power to working-class voters and "ruin the Conservative party."

Even though he resigned, the new law, the Reform Act 1867, passed. It gave many more men the right to vote. Cranborne publicly criticized Disraeli for changing his mind on such an important issue.

In Opposition and New Roles: 1868–1874

In 1868, Robert Cecil's father passed away, and he became the Marquess of Salisbury. This meant he moved from the House of Commons to the House of Lords.

He also became the Chancellor of the University of Oxford and a Fellow of the Royal Society. For a few years, he was also the chairman of the Great Eastern Railway company, helping it recover from financial problems.

Return as Secretary of State for India: 1874–1878

Salisbury returned to government in 1874, again serving as Secretary of State for India under Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli. He also represented Britain at the Constantinople Conference in 1876. Over time, Salisbury and Disraeli, who had not always gotten along, developed a good working relationship.

Foreign Secretary: 1878–1880

In 1878, Salisbury became Foreign Secretary. In this role, he helped lead Britain at the Congress of Berlin, a major international meeting. Britain achieved "peace with honour" at this conference, which meant they got good results without going to war. For his work, he received the Order of the Garter, a high honor.

Leader of the Opposition: 1881–1885

After Disraeli's death in 1881, the Conservative Party faced a period of uncertainty. Salisbury became the leader of the Conservatives in the House of Lords. He eventually became the main leader of the entire party.

More Changes to Voting Laws: The Reform Act of 1884

In 1884, William Ewart Gladstone introduced another Reform Bill. This bill aimed to give voting rights to two million more rural workers. Salisbury and other Conservative leaders agreed to support it only if a plan to redraw voting districts was also introduced.

Salisbury argued that the people had not been asked about these big changes. He believed the House of Lords had a duty to protect the country's interests. After much debate and negotiation, a compromise was reached. The new law made most voting districts roughly equal in size and allowed them to elect one member of Parliament. This system stayed in place until 1918.

First Time as Prime Minister: 1885–1886

Salisbury became Prime Minister for the first time in 1885, leading a government that did not have a clear majority in Parliament.

He was interested in improving housing for working-class people. He wrote an article arguing that poor living conditions harmed people's health and morals. He believed the government had a role in fixing this problem. In July 1885, a new law called the Housing of the Working Classes Act 1885 was passed, which aimed to improve housing.

Because his party did not have a majority, Salisbury could not achieve much at first. However, the Liberal Party split over the issue of Irish Home Rule in 1886. This allowed Salisbury to return to power with a stronger position. Except for a short period when the Liberals were in power (1892–1895), he served as Prime Minister from 1886 to 1902.

Second Time as Prime Minister: 1886–1892

Salisbury was back in office, relying on the support of the Liberal Unionists. To keep this alliance strong, he had to agree to some new laws, including those about Irish land, education, and local councils. His nephew, Arthur Balfour, became well-known for his strong policies in Ireland. Salisbury was also good at dealing with the press, giving them information freely.

Managing Foreign Relations

Salisbury continued to be the Foreign Secretary from January 1887. He was very skilled in diplomacy, avoiding extreme approaches. His policy was to avoid complicated alliances, which was sometimes called "splendid isolation." He successfully settled disagreements with France and other countries over colonial claims.

A major concern was protecting the Suez Canal and the sea routes to India and Asia. He made agreements with Italy and Austria-Hungary to help maintain stability in the Mediterranean region. He also believed in having a strong navy. The Naval Defence Act 1889 allowed for a huge increase in spending on the Royal Navy. This meant Britain's navy would be as strong as the next two biggest navies combined, mainly aimed at France and Russia.

Queen Victoria offered Salisbury the title of Duke twice, but he politely refused. He said that being a Duke was too expensive and that he preferred his older title of Marquess.

Dealing with Portugal in 1890

Britain had a disagreement with Portugal over colonial lands in Africa. Portugal had a "Pink Map" vision for its empire, while Britain had its "Cape to Cairo Railway" plan. After years of talks, Portugal, which was struggling financially, had to give up some territories that are now part of Malawi, Zambia, and Zimbabwe to the British Empire.

Leader of the Opposition Again: 1892–1895

After the 1892 United Kingdom general election, the Liberal Party and Irish Nationalists gained a majority in Parliament. Salisbury resigned as Prime Minister on August 12.

He wrote that the new government, which did not have a majority in England and Scotland, had no right to push for Home Rule for Ireland. He argued that only the House of Lords could truly represent the nation's wishes on such big changes. The House of Lords rejected the second Home Rule Bill in September 1893.

In 1894, Salisbury also became the president of the British Science Association, giving an important speech. The general election of 1895 resulted in a large victory for Salisbury's Unionist party.

Third Time as Prime Minister: 1895–1902

Salisbury was very good at foreign affairs. For most of his time as Prime Minister, he also served as Foreign Secretary. He managed Britain's relationships with other countries, but he did not truly believe in "Splendid isolation" as a goal.

Foreign Policy Challenges

Salisbury faced many challenges around the world. Britain had no strong allies. Germany was becoming a powerful industrial and naval force. France was challenging Britain in Sudan. In the Americas, the U.S. President started a dispute over the border between Venezuela and British Guiana. In Central Asia, Russia and British India were getting closer. In China, other countries wanted to control parts of the country, threatening Britain's economic power.

Tensions with Germany eased in 1890 after a deal where Germany traded land in East Africa for an island off the German coast. However, tensions rose again with the new German Kaiser. France backed down in Africa after the British took control in the Fashoda Incident. The dispute with Venezuela was settled peacefully, and Britain and the U.S. became friends. A treaty with Japan in 1902 helped resolve issues in China.

However, a difficult war, the Second Boer War, started in South Africa in 1899.

The Venezuela Crisis with the United States

In 1895, a border dispute between British Guiana and Venezuela led to a major crisis with the United States. The U.S. supported Venezuela and demanded an explanation from Britain. Salisbury initially refused. The crisis grew when U.S. President Grover Cleveland used the Monroe Doctrine to issue a strong warning. Salisbury's government decided to agree to arbitration. The issue was quickly settled, mostly supporting Britain's border claim. This event helped improve relations between Britain and the United States.

Events in Africa

An agreement with Germany in 1890 settled land claims in East Africa. Britain gained control of Zanzibar and Uganda. In 1896, the German Kaiser sent a telegram congratulating the Boers for fighting off a British raid. This made Britain see Germany as a threat. In 1898, British forces moved into Sudan, taking full control. Britain also settled tensions with France after a confrontation in Fashoda, leading to friendlier relations.

The Second Boer War

After gold was found in the South African Republic (Transvaal) in the 1880s, many British miners moved there. The Transvaal and the Orange Free State were small, independent nations founded by Afrikaners (Dutch descendants). The Afrikaners did not trust the new miners, called "uitlanders," who had to pay high taxes and had few rights. Britain demanded changes, but these were refused. A small British attempt to overthrow the Transvaal president failed in 1895, leading to war.

The war began on October 11, 1899. Britain fought against the two small Boer nations. Prime Minister Salisbury let his Colonial Minister, Joseph Chamberlain, manage the war. The British were overconfident and not fully prepared. The Boers, with fewer soldiers, attacked first and won some early battles.

The British fought back, relieving their besieged cities, and invaded the Boer states. The Boers refused to give up and started fighting a guerrilla war. After two years, Britain, using over 400,000 soldiers, systematically destroyed the resistance. They moved Boer civilians into guarded concentration camps, where many died from disease. The war was very costly, but Britain won. The Conservatives won the 1900 election. The Boers were given fair terms, and their republics became part of the Union of South Africa in 1910.

The war had many critics, especially in the Liberal Party. However, most of the British public supported the war. Journalists, including young Winston Churchill, covered the war extensively.

In 1897, Germany began building a large navy to challenge Britain's naval power. This new policy, called Weltpolitik (world politics), aimed to make Germany a global power. This led to a naval arms race between Britain and Germany.

Britain responded with major changes to its navy. After Salisbury's death, the HMS Dreadnought was launched in 1906. This ship was so advanced that it made all other battleships in the world old-fashioned, setting back Germany's plans.

Historians agree that Salisbury was a very strong and effective leader in foreign affairs. He understood global issues well.

Domestic Policies

At home, Salisbury tried to solve the Irish Home Rule problem by improving conditions in Ireland. He started a land reform program that helped many Irish farmers buy their own land. This greatly reduced complaints against English landlords.

He also supported laws to help teachers save for retirement and to provide education for children with mental or physical disabilities.

Honors and Retirement

In 1895 and 1900, he received honors like Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports and High Steward of Westminster Abbey.

On July 11, 1902, Salisbury resigned as Prime Minister due to his declining health and the death of his wife. His nephew, Arthur Balfour, took over. King Edward VII gave him a special honor, the Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order.

Last Year and Legacy: 1902–1903

In his last year, Salisbury had trouble breathing due to his weight and suffered from a heart condition. He passed away in August 1903 after a fall.

He was buried at St Etheldreda's Church, Hatfield. A monument to him is also in Westminster Abbey.

Historians often describe Salisbury as a traditional, aristocratic conservative leader. He favored careful expansion of the British Empire and resisted big changes to Parliament and voting rights. Many see him as a great foreign minister.

His writings and ideas have received a lot of attention. He is considered one of the most intellectual figures in the Conservative Party's history. Several groups and journals have been named in his honor.

Interestingly, Clement Attlee, a Labour Party Prime Minister (1945–1951), once said that Salisbury was the best Prime Minister of his lifetime.

The British phrase 'Bob's your uncle' is thought to have come from Robert Cecil appointing his nephew, Arthur Balfour, to a high government position.

The city of Fort Salisbury (now Harare) in Zimbabwe was named after him when it was founded in 1890. Other places there, like Hatfield and Cranborne, also bear names connected to him.

He was the only British Prime Minister to have a full beard. At 6 feet 4 inches (193 cm) tall, he was also the tallest Prime Minister.

Family Life

Lord Salisbury was the third son of the 2nd Marquess of Salisbury. In 1857, he married Georgina Alderson, even though his father wanted him to marry someone richer. Their marriage was very happy. They had eight children, and all but one survived. He was a loving father and made sure his children had a much better childhood than he did. At first, he was cut off from his family's money, so he supported his family by working as a journalist. Later, he made up with his father.

- Lady Beatrix Maud Cecil (1858–1950)

- Lady Gwendolen Cecil (1860–1945), who wrote a biography of her father.

- James Edward Hubert Gascoyne-Cecil, 4th Marquess of Salisbury (1861–1947)

- Lord Rupert Ernest William Cecil, Bishop of Exeter (1863–1936)

- Lord Edgar Algernon Robert Cecil, 1st Viscount Cecil of Chelwood (1864–1958)

- Hon. Fanny Georgina Mildred Cecil (1865–1867)

- Lord Edward Herbert Cecil (1867–1918)

- Lord Hugh Richard Heathcote Cecil, 1st Baron Quickswood (1869–1956)

Salisbury had a condition called prosopagnosia, which made it hard for him to recognize familiar faces.

Cabinets of Lord Salisbury

- First Salisbury ministry (1885–1886)

- Second Salisbury ministry (1886–1892)

- Unionist government (1895–1902)

See also

In Spanish: Robert Gascoyne-Cecil para niños

In Spanish: Robert Gascoyne-Cecil para niños