Marc Bloch facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Marc Bloch

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 6 July 1886 |

| Died | 16 June 1944 (aged 57) |

| Cause of death | Execution by firing squad |

| Resting place | Le Bourg-d'Hem |

| Education | Lycée Louis-le-Grand |

| Alma mater | École Normale Supérieure |

| Occupation | Historian |

| Spouse(s) | Simonne Vidal |

| Children | Alice and Étienne |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

French Army |

| Years of service | 1914–1918, 1939 |

| Rank | Captain |

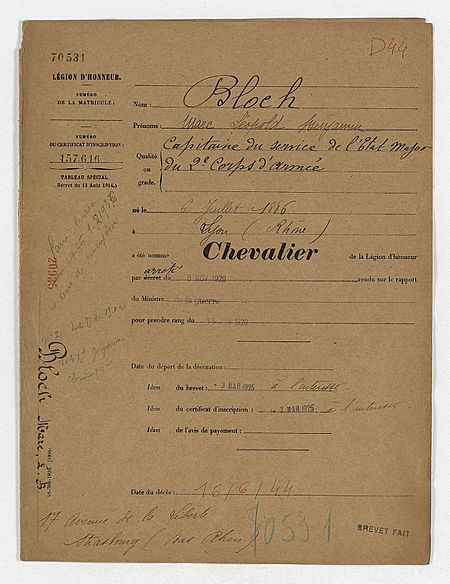

| Awards | Legion of Honor War Cross (1914–1918) War Cross (1939–1945) |

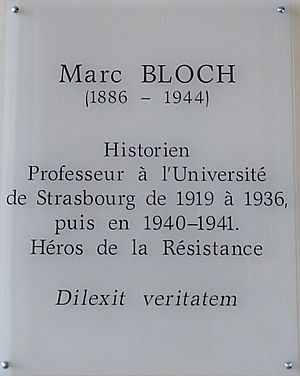

Marc Léopold Benjamin Bloch (born July 6, 1886 – died June 16, 1944) was an important French historian. He helped start the Annales School, a new way of studying history in France. Bloch was an expert in medieval history, which means he studied the Middle Ages. He wrote many books about Medieval France. He taught at the University of Strasbourg (1920–1936), the University of Paris (1936–1939), and the University of Montpellier (1941–1944).

Marc Bloch was born in Lyon, France, into an Alsatian Jewish family. He grew up in Paris, where his father, Gustave Bloch, was also a historian. Marc went to top schools in Paris, including the École Normale Supérieure. From a young age, he was affected by unfair treatment of Jewish people during the Dreyfus affair.

During World War I, Bloch served in the French Army. He fought in major battles like the First Battle of the Marne and the Somme. After the war, he earned his doctorate in 1918 and became a lecturer at the University of Strasbourg. There, he met modern historian Lucien Febvre, and they became close friends and colleagues. Together, they founded the Annales School and started the history journal Annales d'histoire économique et sociale in 1929. Bloch believed history should use ideas from many subjects, like geography, sociology, and economics. He became a professor at the University of Paris in 1936.

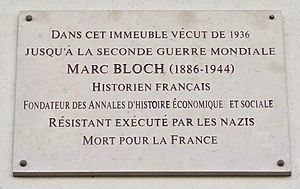

When World War II began, Bloch volunteered for the army again. He worked in logistics, helping to manage fuel supplies. He was involved in the Battle of Dunkirk and briefly went to Britain. He tried to go to the United States but couldn't. Back in France, new rules against Jewish people made it hard for him to work. He managed to get a special permit to keep teaching but had to leave Paris. His apartment was searched by the Nazis, and his books were taken. He also had to leave the Annales journal. Bloch worked in Montpellier until November 1942, when Germany took over all of France. He then joined the French Resistance, a secret group fighting against the Nazis. He worked as a messenger and translator. In 1944, he was captured in Lyon and was killed by a firing squad. Some of his most important books, like The Historian's Craft and Strange Defeat, were published after his death.

After the war, Marc Bloch was highly respected by French historians because of his studies and his brave death in the Resistance. He was even called "the greatest historian of all time." Later, historians looked at his work more closely, seeing both its strengths and some weaknesses.

Contents

Early Life and Schooling

His Family and Home

Marc Bloch was born in Lyon on July 6, 1886. He had an older brother, Louis Constant Alexandre. Their family were Alsatian Jews. They were not very religious but were very loyal to France. His family had lived in Alsace for many generations. In 1871, France lost Alsace to Germany after a war. Marc's father, Gustave Bloch, was a well-known historian. He taught at the Sorbonne University in Paris, so the family moved there. Marc's father started teaching him history when he was young. Marc's future colleague, Lucien Febvre, visited the Bloch family in 1902. He remembered Marc as a "slender adolescent with eyes brilliant with intelligence."

Growing Up and Education

Marc Bloch grew up during a time of change in France. When he was nine, the Dreyfus affair happened. This was a big event where a Jewish army officer was unfairly accused of treason. It showed a lot of unfair treatment against Jewish people in Europe. This event deeply affected Bloch. He was 11 when writer Émile Zola spoke out against the unfairness. Bloch's father was very involved in supporting Dreyfus, and Marc agreed with him.

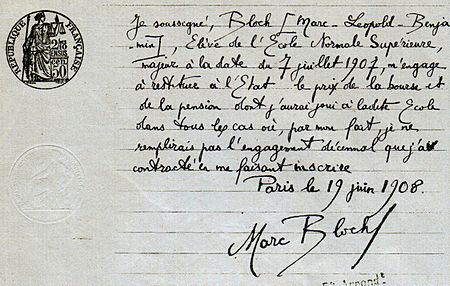

Bloch went to the famous Lycée Louis-le-Grand for three years. He was always at the top of his class and won many awards. In 1903, he passed his final exams with "very good" grades. The next year, he received a scholarship to study at the École Normale Supérieure (ÉNS), where his father also taught. Here, he learned history from Christian Pfister and Charles Seignobos. They believed history should focus on big themes and important events. Another person who influenced Bloch was the sociologist Émile Durkheim. Durkheim believed in connecting different subjects, which Bloch later did in his own work. In 1905, all French men had to serve in the army for two years. Bloch joined the 46th Infantry Regiment.

First Studies and Research

By this time, French universities were changing. Historians wanted to use more scientific methods. Bloch graduated in 1908 with degrees in both geography and history. He respected historical geography, a field that combined history and geography. In 1909, he went to Germany to study demography (the study of populations) and religion.

He returned to France and began researching the medieval Île-de-France region for his main university paper, called a thesis. This was his first time focusing on rural history. He studied where serfdom (a system where peasants were tied to the land) was common. He learned that serfdom was mostly based on old customs. His studies helped him become a mature scholar and showed him how other subjects could help understand history. He looked at trade, money, religion, and art. His thesis was about 10th-century French serfdom. It was called Rois et Serfs, un Chapitre d'Histoire Capétienne (Kings and Serfs, a Chapter of Capetian History). After graduating, he taught at two high schools. He also reviewed a book by Febvre. Bloch planned to turn his thesis into a book, but World War I started.

Serving in World War I

Both Marc and Louis Bloch volunteered for the French Army. Marc had not liked the army before, but he respected the ordinary soldiers. He was one of over 800 students from his school who joined the army; many of them died. On August 2, 1914, he joined the 272nd Reserve Regiment. He was sent to the Belgian border and fought in the Battle of the Meuse. His regiment had to retreat and then fought in the First Battle of the Marne. Bloch led his troop bravely, even though they had many casualties. He enjoyed the early days of the war, expecting it to be short and glorious.

Bloch spent most of the war in the infantry. He started as a sergeant and became the head of his section. He kept a detailed war diary, which helped him understand history better. The war came at a difficult time for his studies.

For the first time, Bloch lived and worked closely with people from different backgrounds, like shop workers and laborers. He felt a strong sense of friendship with them. This experience made him rethink his ideas about history and life. He was especially moved by how people worked together in the trenches. He said he knew no better men than those he spent four years with. He rarely spoke well of the French generals.

Besides the Marne, Bloch fought in the battles of the Somme, the Argonne, and the final German attack on Paris. He survived the war, which he called an "honor." However, he lost many friends and colleagues. He was wounded twice and received awards for his bravery, including the Croix de Guerre and the Légion d'Honneur. He started as a non-commissioned officer and became a captain. He was a good and brave soldier, believing that to persuade others to be brave, you must be brave yourself.

During his service, Bloch got severe arthritis. He often had to go to thermal baths for treatment. He later said he remembered little of the historical events he was in, only "a discontinuous series of images." He also felt the war was "four years of fighting idleness." He left the army on March 13, 1919.

Career as a Historian

Starting His Career

The war changed Bloch's approach to history, though he never said it was a turning point. After the war, he rejected the old ways of studying history, which focused on politics and biographies. He also disliked simply collecting facts. In 1920, he became an assistant lecturer of medieval history at the University of Strasbourg. This region had just been returned to France. Strasbourg University had one of the biggest academic libraries in the world. Bloch used its resources to become an expert on the European Middle Ages. He also taught French to German students.

Bloch worked very hard at Strasbourg, calling these his most productive years. His teaching style could be a bit cold, but he was also charismatic. He was greatly influenced by Durkheim, who believed historians and sociologists should work together. Bloch often spoke about Durkheim's influence.

At Strasbourg, he met Febvre again, who was now a leading historian of the 16th century. Their meeting was very important for 20th-century history. They worked closely together for the rest of Bloch's life. Febvre was older and likely influenced Bloch a lot. They lived in the same area and often went on walks together.

By 1920, Bloch's main ideas about history were set. He published his thesis that year. It was shorter than planned because of the war, but it showed he was a skilled medievalist. He started publishing articles and his first major book, Les Rois Thaumaturges (The Royal Touch), in 1924. In 1928, he gave lectures in Oslo, Norway, where he first shared his ideas on "total, comparative history." He argued for breaking down national borders in historical research and using other subjects to understand history better.

New Ideas: Comparative History and the Annales

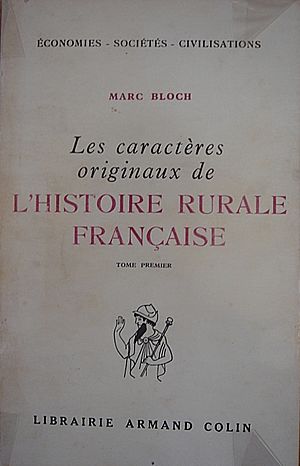

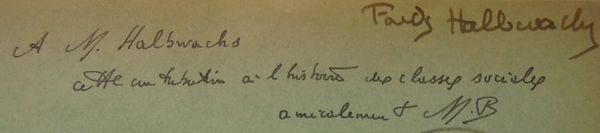

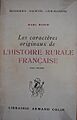

His Oslo lecture led to his next book, Les Caractères Originaux de l'Histoire Rurale Française (French Rural History). In the same year, he and Febvre started the historical journal Annales. One of their goals was to change history from focusing only on facts and politics to including more about people's lives. They wanted to use sociological methods. The journal almost never used simple storytelling history.

The first issue of Annales said its goals were to stop dividing history into artificial periods, to bring history and social science together, and to welcome all ways of thinking into history. Because of this, Annales often included comments on current events, not just past ones. Editing the journal helped Bloch connect with scholars across Europe. Annales was unique because it had a clear method for studying history. It also had a left-wing viewpoint. Henri Pirenne, a Belgian historian, strongly supported the journal. He was a link between French and German historians before the war. Fernand Braudel, who later became important in the Annales School, said Bloch was like the CEO of the journal, and Febvre was like the foreign minister.

Bloch used comparative history to find unique things in societies. He believed it was a new way to study history. Pirenne became a close friend of Bloch and Febvre. Bloch said Pirenne's approach should be a model for historians. The three men wrote to each other regularly until Pirenne's death in 1935. Bloch reviewed over 700 books for Annales in the 1920s and 1930s. These reviews showed how his ideas were developing.

Moving to Paris

In 1930, both Febvre and Bloch wanted to move to Paris, but they didn't get positions at first. Three years later, Febvre was elected to the Collège de France and moved to Paris. This put some strain on his friendship with Bloch, though they still wrote to each other often. In 1934, Bloch was invited to lecture in London, where he met important British historians. He also tried to get British historians interested in Annales. He felt he had more in common with academic life in England than in France.

During this time, he supported the Popular Front, a group of left-wing political parties. He was against the rise of fascism but also against trying to fight it with emotional appeals. Febvre and Bloch were both left-wing, but with different ideas.

In 1934, Bloch was considered for a teaching position at the Collège de France. This was Bloch's "dream" job because it focused on personal research. However, he was not chosen. Bloch thought this might be due to unfair rules against Jewish people. Febvre blamed it on the academic world's distrust of Bloch's new approach to history.

Joining the Sorbonne

Henri Hauser retired from the Sorbonne in 1936, and his position in economic history became open. Bloch applied and was approved. This was a more demanding job than the one at the Collège de France. Bloch had wanted to work at the Sorbonne since 1928. His first lecture was about history as a never-ending process. His years at the Sorbonne were very productive. By this time, he was considered the most important French historian of his age. In 1936, he thought about using the ideas of Karl Marx in his teaching to bring "some fresh air" to the Sorbonne.

Around this time, Bloch and his family visited Venice. They lived in Paris, near the Hôtel Lutetia.

By now, Annales was published six times a year. In 1938, the publishers stopped supporting it, and the journal faced financial problems. It moved to cheaper offices and raised its prices. Febvre and Bloch started to disagree on the direction of the journal. Febvre wanted it to be a "journal of ideas," while Bloch saw it as a way to share information across different subjects.

By early 1939, war seemed likely. Bloch, despite his age, was a reserve captain in the army. In autumn 1939, just before the war began, Bloch published the first volume of Feudal Society.

World War II and the Resistance

On August 24, 1939, at 53 years old, Bloch was called to serve in the army again. He was a fuel supply officer, responsible for managing the French Army's fuel. During the first months of the war, known as the Phoney War, he was stationed in Alsace. He didn't feel the same strong patriotism as in World War I. He felt he had been treated unfairly, which made him feel distant from his comrades. His main duty was to help civilians move away from the Maginot Line. He was later transferred to the 1st Army headquarters, working with the British.

Bloch was often bored between 1939 and May 1940 because he had little work. To pass the time, he started writing a history of France. This unfinished work later became the basis for The Historian's Craft. He turned down chances to lecture in Belgium and Norway because he wanted to be closer to his family. He also refused an invitation to go to New York because his whole family couldn't get visas.

France Falls to Germany

In May 1940, the German army defeated the French. Bloch, facing capture, dressed in civilian clothes and lived under German occupation for two weeks before returning to his family. He fought in the Battle of Dunkirk and was evacuated to England. He chose to return to France the same day because his family was there.

Bloch felt the French Army lacked the strong team spirit of World War I. He thought the French generals of 1940 were as uncreative as those in the first war. He believed France fell because its generals failed to use their best qualities. He was shocked by the defeat, seeing it as worse than previous French defeats. Bloch understood that France's defeat was due to its failure to use motorized units effectively and its slow retreat. He wrote in Strange Defeat that a fast, motorized retreat might have saved the army.

Two-thirds of France was occupied by Germany. Bloch was released from the army after Philippe Pétain's government signed an agreement, forming Vichy France in the southern part of the country. Bloch moved south. In January 1941, he applied for and received one of only ten special permits allowing Jewish academics to work under the Vichy government. This was likely because he was so well-known in history. He was allowed to work at the "University of Strasbourg-in-exile" and at the University of Montpellier. The dean at Montpellier, Augustin Fliche, was not friendly towards Bloch. Bloch criticized the Vichy government's propaganda, saying their idea of a perfect rural France was impossible because it had never existed.

Difficulties with Febvre

Bloch's professional relationship with Febvre also became strained. The Nazis wanted Jewish people removed from French editorial boards. Bloch wanted to resist this, but Febvre wanted Annales to survive at all costs. He believed they should make concessions to keep French intellectual life alive. Bloch refused to "fall into line." Febvre asked Bloch to resign as co-editor, fearing Bloch's involvement as a Jew would stop the journal's distribution. Bloch had to agree, and Febvre became the sole editor, changing the journal's name. Bloch had to write for it using a fake name, Marc Fougères. The journal's bank account was also in Bloch's name and had to be changed. Bloch was offended when Febvre suggested that another historian, Hauser, had more to lose than them. Bloch replied that his children were in danger because they were Jewish, unlike Febvre's.

The historian André Burguière suggests Febvre didn't fully understand the danger Bloch and other French Jews faced. Their relationship worsened when Bloch's library and papers were taken from his Paris apartment by the Nazis in 1942. Bloch blamed Febvre, believing he could have done more to prevent it.

Bloch's mother had recently died, and his wife was ill. He faced daily harassment. On March 18, 1941, Bloch made his will. He emphasized that no one had the right to avoid fighting for their country. In March 1942, Bloch and other French academics refused to join a group for Jews created by the Vichy government.

Joining the French Resistance

In November 1942, the German Army took over all of France. This led Bloch to join the French Resistance between late 1942 and March 1943. Bloch was careful not to join just because he was Jewish. He believed there could be "no salvation where there is not some sacrifice." He sent his family away and returned to Lyon to join the underground.

Despite knowing many resistance fighters, Bloch found it hard to join because of his age. He told his wife he "didn't know it is so difficult to offer one's life." A fellow resistance member later said how this "eminent professor came to put himself at our command simply and modestly." Bloch used his skills to help them, writing propaganda and organizing supplies. He became a regional organizer and edited an underground newsletter. He used different fake names. Bloch often moved around, using "archival research" as an excuse for his travels. He kept all his notes in code. For the first time, Bloch had to think about the role of individuals in history, not just groups.

His Death

Bloch was arrested in Lyon on March 8, 1944, during a large roundup by the Vichy police. He was handed over to the Gestapo (Nazi secret police). Bloch was using the name "Maurice Blanchard." He was described as an "ageing gentleman, rather short, grey-haired, bespectacled, neatly dressed." The Gestapo searched his rented room and found a radio transmitter and many papers. It's thought someone working in the shop below told the authorities about him. Bloch was imprisoned in Montluc prison. His wife died while he was in prison. He became seriously ill with a lung infection. It was said he didn't give any information to his questioners and taught French history to other prisoners.

On June 6, 1944, the Allies invaded Normandy. The Nazis wanted to get rid of their prisoners in France. Between May and June 1944, the Nazis shot about 700 prisoners in different places to keep it secret. Marc Bloch was one of 26 Resistance prisoners taken from Montluc and driven towards Trévoux on the night of June 16, 1944. One man managed to escape and later gave a detailed report. The bodies were found on June 26.

At his burial, Bloch's own words were read. He proudly spoke of his Jewish background but said he was "quite simply French before anything else." He asked for no traditional prayers and for his gravestone to say dilexi veritatem ("I have loved the truth"). In 1977, his ashes were moved, and his gravestone was carved as he wished.

Febvre had not approved of Bloch joining the Resistance, thinking it was a waste of his talents. However, many other French thinkers also died in the Resistance. Febvre continued publishing Annales, though in a changed form. After the war, when classes returned to normal, Febvre was booed by students at the Sorbonne because of his actions during the war.

Important Books and Ideas

Bloch's first book was L'Ile de France, published in 1913. It was a small, easy-to-read book that combined geography, language, and archaeology. His early important work, Rois et Thaumaturges (Kings and Miracles), was published in 1924. In this book, he studied the medieval belief in the "royal touch," where kings were thought to heal people by touching them. He looked at how kings used this belief for propaganda. This book was one of the first examples of Bloch using ideas from many different subjects, like anthropology, medicine, and psychology. It's considered his first great work.

In 1931, Les caractéres originaux de l'histoire rurale francaise (The Original Characteristics of French Rural History) was published. Bloch called it "my little book." In it, he used both traditional research methods (like studying old documents) and his new, multi-subject approach, with a lot of focus on maps. He believed that traditional research was still very important. This book, considered one of his best, studies how physical geography affected the development of political systems. Bloch looked at history by starting from the present and going back in time, using things like 18th- and 19th-century maps to understand earlier times.

Later Writings and Books After His Death

La Société Féodale (Feudal Society) was published in two parts in 1939. It was translated into English in 1961. Bloch called it a "sketch," but it is considered his most lasting work and is still used today. In Feudal Society, he used research from many subjects to examine feudalism in a broad way, even including a study of feudal Japan. He also compared areas where feudalism was introduced (like England after the Norman conquest) and where it never developed (like Scotland). Bloch defined feudal society as a time when peasants were ruled by an upper-class.

Historians consider The Royal Touch, French Rural History, and Feudal Society as Bloch's most important works. His last two books, The Historian's Craft and Strange Defeat, are different because they talk about recent events that Bloch was personally involved in. They were published after his death in 1949. The Historian's Craft is described as "beautifully sensitive and profound." Bloch wrote it to his son, Étienne, who asked, "what is history?" In its introduction, Bloch wrote to Febvre about their shared work for a "wider and more human history."

Strange Defeat is a strong analysis of why France fell in 1940. Bloch said the book was more than a personal memory; it was his statement and testament. In it, he honestly looked at his own generation's failures. Bloch blamed failures in the French mindset, the low morale of soldiers, and poor training of officers. He criticized the focus on testing in education, which he felt made people less original and curious. Strange Defeat is seen as Bloch's examination of France between the two World Wars.

A collection of his essays was published in English in 1961 as Land and Work in Medieval Europe. Bloch liked writing long essays. One famous essay was about the water mill, which he saw as a key technological advance. Another was about why Genoa and Florence were the first European cities to use gold coins.

How Bloch Studied History

Bloch was a strong debater in history discussions. He often showed the weaknesses in other historians' arguments. His way of studying history was a reaction against the popular ideas in France at the time, which were based on the German School of history. This school focused very much on detailed administrative history. Bloch respected earlier historians but felt they treated history like detective work, focusing too much on facts rather than the human experience. He believed it was wrong for historians to focus only on evidence without understanding the people of that time.

Bloch was influenced by historians who wrote comparative history and social history, and by sociologists like Durkheim. Bloch's focus on comparative history went back to the Enlightenment, when writers wanted to use philosophy to study the past. Bloch criticized the "German-dominated" way of studying political economy, which he found too simple. He also disagreed with ideas about racial theories of national identity. Bloch believed that political history alone could not explain deeper social and economic trends.

Bloch did not see social history as a separate field. He believed all history was part of social history. He and Febvre called this "total history." It meant not just focusing on facts like dates of battles, but on everything that made up a society. Bloch told Pirenne that a historian's most important quality was being surprised by what they found. Bloch identified two types of historical periods: generational eras (which changed quickly) and eras of civilization (which changed slowly). In the latter, he included physical, structural, and psychological parts of society.

Bloch started what modern French historians call the "regressive method." This method looks at problems in later historical periods and uses them to understand what things might have been like centuries earlier. This was helpful for studying old village communities, as old customs often stayed the same. Bloch studied old peasant tools in museums and watched people use them. He believed that observing a plough or a harvest was observing history, as the technology and techniques often hadn't changed for hundreds of years. He focused on the group, the community, the society, rather than individual people. He wrote about peasants as a group, not individual peasants.

Bloch said his area of study was the comparative history of European society. He didn't want to be called just a "medievalist." He believed history was the "science of movement." He didn't think you could protect the future by only studying the past. His work didn't use a completely new approach. Instead, he wanted to combine older ways of thinking into a new, broad approach to history. He criticized historians who focused too much on the "origins" of something, rather than studying the thing itself.

Bloch's comparative history led him to connect his research with many other subjects: social sciences, languages, literature, folklore, geography, and farming. He didn't limit himself to French history. He wrote about medieval history in Corsica, Finland, Japan, Norway, and Wales. Bloch was very smart and knew many languages. His clear writing and way of looking at history in social terms had a big impact. He dreamed of a world without borders, where history could be studied from a global perspective.

What Bloch Was Interested In

Bloch was interested not just in periods of history, but in the importance of history itself as a way of thinking. He believed historians should not stick too strictly to their own subject. Much of his writing in Annales stressed the importance of finding evidence in other fields, like archaeology, ethnography, geography, literature, psychology, sociology, technology, and statistics. He felt this allowed for a broader and deeper understanding of the past. Bloch's favorite example of how technology affects society was the watermill. It was known but little used in ancient times, became important in the early Middle Ages, and later became a valuable resource controlled by nobles.

Bloch also emphasized the importance of geography in studying history, especially rural history. He thought they were basically the same subjects, but he criticized geographers for not considering historical time or human actions. He described a farmer's field as "fundamentally, a human work, built from generation to generation." Bloch also disagreed with the idea that rural life never changed. He believed that farmers in Roman times were different from those in the 18th century. He saw similar farming developments in England and France. Bloch was also very interested in languages and how they could be used in comparative history. He believed this method could stop historians from ignoring the bigger picture while doing detailed local research.

Bloch spoke many languages and impressed people with his wide knowledge. His clear writing and way of looking at historical issues in social terms had a strong impact on history.

Personal Life

Bloch was not a tall man, about 5 feet 5 inches, and dressed elegantly. He had expressive blue eyes that could be "mischievous, inquisitive, ironic and sharp." Febvre said that when he first met Bloch in 1902, he was a slender young man with a "timid face." Bloch was proud of his family's history of defending France. He wrote that his family had always been strong supporters of France.

Bloch strongly supported the Third Republic (the French government at the time) and had left-wing political views. He was not a Marxist, but he admired Karl Marx as a historian. He saw politics as moral choices. However, he didn't let politics enter his historical work. He believed society should be led by young people.

Bloch was a very private person. In July 1919, he married Simonne Vidal, a "cultivated and discreet" woman. Her father was a wealthy and influential man, which allowed Bloch to focus on his research without worrying about money. Bloch later said he found great happiness with her. They had six children, four sons and two daughters. The oldest were Alice and Étienne. Bloch took a great interest in his children's education and helped them with homework. However, he could be very critical of his children, especially Étienne.

Bloch did not follow a formal religion. His son Étienne said that his father showed "not even the slightest trace of a supposed Jewish identity" in his life or writings, and that "Marc Bloch was simply French." Some of his students thought he was an Orthodox Jew, but this was not true. While his Jewish roots were important to him, it was mostly because of the unfair treatment during the Dreyfus years. He said he only emphasized his Jewishness when facing someone who was unfair to Jews.

Bloch's brother Louis became a doctor but died young in 1922. Their father died the next year. After these deaths, Bloch took care of his aging mother and his brother's widow and children. Bloch was very focused on truth and hated dishonesty. He also disliked German nationalism because of the wars. He rarely discussed German historians, even those he might have agreed with. He respected English historians and their long tradition of rural history.

Legacy and Influence

Some historians believe that if Bloch had survived the war, he might have become the Minister of Education in France and reformed the education system. In 1948, his son Étienne offered his father's papers to the French National Archives, but they were rejected. The papers were then kept at the École Normale Supérieure for decades.

Historian Peter Burke called Bloch the leader of the "French Historical Revolution." Bloch became a hero for new historians after the war. He has been called "one of the most influential historians of the twentieth century" and "the greatest historian of modern times." However, this reputation grew mostly after his death. Some say his work was overshadowed by his heroic death, leading to too much praise. This has made it harder for historians to look at his work critically.

Around the year 2000, there was a lack of critical study of Marc Bloch's writings. His legacy has also been complicated by the second generation of Annalists, led by Fernand Braudel, who used Bloch's story to create a "founding myth." The parts of his life that made Bloch easy to admire include being a "Frenchman and Jew, scholar and soldier, staff officer and Resistance worker."

The first critical biography of Bloch was published in 1989. Since then, new studies have been more objective about Bloch's weaknesses. For example, his work on a specific historical document was later criticized by experts. Some colleagues said Bloch could be "cold, distant, and both timid and hypocritical" because of his strong views on the French education system. Bloch's idea that individuals don't play a big role in changing society has been questioned. Even Febvre, reviewing Feudal Society, suggested Bloch had ignored the individual's role.

Bloch has also been criticized for sometimes giving complete answers when they weren't fully supported, and for ignoring inconsistencies. Some historians also say his division of the feudal period into two distinct times was artificial. Bloch sometimes seemed to ignore important historians of his time. Some say that the sociological side of Bloch's work sometimes made his historical writing less precise.

Comparative history remained a debated topic after Bloch's death. Some believe that if Bloch had lived, his views on history might have changed again, even moving away from the school he founded. What made Bloch different was his focus on being clear about his methods, while earlier historians focused on clear data. He constantly questioned himself. His legacy is not just in his books, but in his influence on a whole generation of French historians. Bloch's focus on rural and village society influenced later historians. His combination of economics, history, and sociology was ahead of its time.

The English journal Past & Present was directly inspired by Annales. Michel Foucault said that what Bloch, Febvre, and Braudel showed for history could also be shown for the history of ideas. Bloch's influence spread beyond history after his death. In the 2007 French presidential election, Bloch was quoted many times by politicians. In 1977, Bloch received a state reburial. Streets, schools, and universities have been named after him. A conference was held in Paris in 1986 to celebrate 100 years since his birth, attended by historians and anthropologists.

Awards and Honors

- Knight of the Legion of Honour

- Croix de Guerre 1914-1918 (War Cross 1914-1918), with 4 mentions for bravery

- Croix de Guerre 1939-1945 (War Cross 1939-1945), with 1 mention for bravery

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Marc Bloch para niños

In Spanish: Marc Bloch para niños

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |