Mixtec Culture facts for kids

|

|

| Religion | Mixtec religion |

|---|---|

| Geographical range | Present day Mexico

|

| Period | 1500 BC |

| Dates | 1500 BC - 1523 AC |

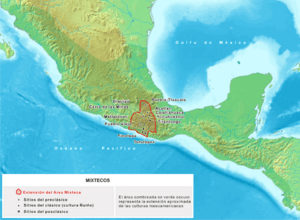

The Mixtec culture (also known as the Mixtec Civilization) was an ancient group of people in Mexico. They lived before the Spanish arrived. These people were the ancestors of today's Mixtec people. They called themselves ñuu Savi, which means "people of the rain". Their culture started around 1500 BC and lasted until the Spanish conquest in the early 1500s. Their home was a mountainous area called La Mixteca. This region is found in the modern Mexican states of Puebla, Oaxaca, and Guerrero.

The Mixtec culture has one of the longest histories in Mesoamerica. It began when people speaking the Otomanguean language started to develop their own unique ways in Oaxaca. The Mixtecs shared many traditions with their neighbors, the Zapotecs. Both groups even called themselves "people of the rain" or "people of the cloud." While the Zapotecs built large cities like Monte Albán, the Mixtecs lived in many smaller towns across the mountains. Mixtecs and Zapotecs always had strong connections. Mixtec goods were even found as luxury items in the Olmec heartland.

During the Classic period, great cities like Teotihuacán and Monte Albán grew powerful. This also helped the Mixtec region called Ñuiñe (Lowland Mixteca) to flourish. In places like Cerro de las Minas, special stone slabs called stelae were found. These stelae show a type of writing that mixed ideas from Monte Albán and Teotihuacán. You can also see Zapotec influence in the many urns found in the Lowland Mixteca. These urns often show the Old God of Fire. At the same time, the Highland Mixteca saw some cities decline. The power in Ñuiñe led to fights between cities. This is why many Ñuiñe cities were built with strong defenses. When Teotihuacán and Monte Albán declined, so did the Ñuiñe culture. By the 7th and 8th centuries, many old traditions of the Lowland Mixteca were forgotten.

The Mixtec culture truly thrived from the 13th century onwards. A powerful leader named Ocho Venado (Eight Deer) helped the Mixtecs expand their territory. He founded the kingdom of Tututepec on the coast. Then, he led military campaigns to unite many states under his rule. Important places like Tilantongo (Ñuu Tnoo Huahi Andehui) joined his kingdom. This was possible because of his alliance with Cuatro Jaguar, a Toltec lord from Ñuu Cohyo (Tollan-Chollollan). Ocho Venado's rule ended when he was assassinated.

Throughout the Postclassic period, Mixtec and Zapotec states formed many alliances through marriage. However, they also became more competitive. Despite this, they worked together to fight off attacks from the Mexica people. Mexico-Tenochtitlan and its allies conquered powerful states like Coixtlahuaca. This city became a province that paid tribute to the Aztec Empire. But Tututepec (Yucudzáa) stayed independent. It even helped the Zapotecs resist in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. When the Spanish arrived, many Mixtec lords chose to become vassals of Spain. They kept some of their special rights. Other lords tried to fight but were defeated.

Contents

Where Did the Mixtecs Live?

The Mixtec people lived in southern Mexico. This area is known as La Mixteca. It covers more than 40,000 square kilometers. Today, it includes parts of southern Puebla, eastern Guerrero, and western Oaxaca. The Mexica people called this land Mixtecapan, meaning "Country of the Mixtecs." In the old Mixtec language, it was called Ñuu Dzahui.

The Mixtecs never formed one big political country. Instead, they lived in many small states. The largest of these was formed under Ocho Venado in Tilantongo. The Mixtec land is very diverse. It has large mountain ranges like the Sierra Mixteca. Its exact borders are not always clear. This is because Mixtec people often lived alongside other groups.

La Mixteca is usually divided into different regions. The simplest way to divide it is into Highland Mixteca and Lowland Mixteca. The Highland Mixteca is in the Sierra Mixteca. The Lowland Mixteca is in the foothills of the Sierra Madre del Sur.

The Highland Mixteca has valleys like Tlaxiaco and Nochixtlán. It is a very mountainous area where the Sierra Madre del Sur and the Neovolcanic Axis meet. The climate here is cool to cold and more humid. Many rivers start in the Highland Mixteca.

North of the Highland Mixteca is the Lowland Mixteca. This area is lower in altitude, usually below 2000 meters. Because of this, the Lowland Mixteca is hotter and drier. It was called ñuiñe, meaning "Hot Land" in Mixtec. Most of this area is part of the Balsas River basin. The climate is like a dry forest. It has plants that can live in dry conditions, and others that grow during the rainy season.

Mixtec Geographic Zones

The Mixtec civilization settled in three main areas:

- Lowland Mixteca: This is in the northwestern part of Oaxaca and the southeastern part of Puebla.

- Highland Mixteca: This covers the northwest of Guerrero and the west of Oaxaca.

- Coastal Mixteca: This is the Costa Chica region, shared between Oaxaca and Guerrero.

The Mixtec Origin Story

Mixtec stories about how the world began are similar to other Mesoamerican myths. Like the Mexica or the Maya, the Mixtecs believed they lived in the "era" of a Fifth Sun. They thought the world had been created and destroyed many times before.

In the beginning, everything was mixed up. Two spirits, Uno Venado-Serpiente de Jaguar and Uno Venado-Serpiente de Puma, flew in the air. They were like the "Two Lords" who represent the balance of the universe. In the Mixtec story, these two gods separated light from darkness and earth from water. They created four other gods. These four gods then created humans from corn.

One of these four gods was Nueve Viento, also known as the Feathered Serpent. He had a son who challenged the sun, the lord of La Mixteca. This myth tells how the Arrowman of the Sun shot arrows at the sun. The sun fought back with its rays. They fought until sunset, when the sun fell wounded. This is why sunsets are flesh-colored. The Arrowman of the Sun feared the sun would return. So, he brought his people to settle on the land he had won. He told them to plant corn fields that very night. When the sun rose the next day, it could do nothing. This is how the Mixtecs became the owners of the region, by both divine and military right.

The Mixtecs believed they came from the sons of the Apoala tree. One of these sons defeated the Sun and won the land for the Mixtec people. The most important god for the Mixtecs was Dzahui, the god of rain. He was also the protector of the Mixtec nation. Another important god was Nueve Viento-Coo Dzahui. He was a hero who taught them about farming and civilization.

Mixtec History

The Mixtecs are one of the oldest groups in Mesoamerica. Their language is part of the Mixtec language group. This group is related to Zapotec and Otomi. People have lived in La Mixteca since about 5000 BC. However, the Mixtec culture as we know it began after farming developed in Mesoamerica.

Around 3000 BC, the first farming villages appeared. Their economy relied on four main crops: chili, corn, beans, and squash. Two thousand years later, during the Middle Preclassic period, Mixtec towns grew larger. They became part of the big trade network that connected all Mesoamerican peoples. Like most Mesoamerican societies, the Mixtecs were not one unified country. They were organized into small states. These states had several towns linked by a system of power.

We know less about Mixtec history during the Preclassic and Classic periods. We know more about their flourishing period, the Postclassic. During the Postclassic, the city of Tututepec grew powerful. It was founded by Ocho Venado. Tututepec came to control a large area. It also formed alliances with other states in central Mesoamerica. When the Spanish arrived in the 1500s, most of La Mixteca peacefully joined them. Only a few places, like Tututepec, resisted.

Early Mixtec Settlements (Preclassic Period)

The first settled communities in La Mixteca appeared around 1600 BC. These early farming villages were similar to those in other parts of Mesoamerica. However, Mixtec communities did not grow as large as cities like San José Mogote or Monte Albán in the Oaxaca Valleys. Mixtec settlements were small farming villages. But they were already part of the larger Mesoamerican trade network.

For example, Olmec art influenced pottery in the Highland Mixteca. Figurines with Olmec designs were found in sites like Huamelulpan. Also, Olmec areas had pottery made in Tayata, a Mixtec region. In these early times, Mixtec society was not very structured. Homes looked similar, and buildings did not have clear special uses. This shows that social differences were just starting to appear.

By the end of the Middle Preclassic, some towns in Highland Mixteca grew to have thousands of people. These included Monte Negro and Huamelulpan. In the Lowland Mixteca, Cerro de las Minas began to flourish. During this time (around 5th century BC to 2nd century AD), Mixtec societies became more structured. Public buildings appeared in towns like Yucuita. This shows the start of the first states based on powerful leaders. These states controlled small areas, often less than 100 square kilometers.

The growth of Mixtec cities happened at the same time as the Zapotec state of Monte Albán. Monte Albán was much larger and expanded its territory. Mixtec cities were smaller. Monte Albán's influence was clear in La Mixteca. Pottery in Highland Mixteca was similar to Zapotec pottery. Inscriptions using the Zapotec writing system were also found. However, there is no proof that Monte Albán controlled the Mixtecs politically. These similarities likely show a shared cultural development.

Mixtec Golden Age (Classic Period)

The Classic Period for the Mixtec culture was roughly from the 1st to the 8th or 9th centuries. During this time, large cities appeared across Mesoamerica. These cities had specialized areas and clear social classes. The influence of Teotihuacán was felt everywhere. Trade between towns became stronger.

The history of the Mixtec people in this period is not fully known. In the Classic period, political power centers shifted in La Mixteca. Old Mixtec states passed on some traditions to new ones. Power was still divided among many towns. In Highland Mixteca, Yucuñudahui replaced Yucuita as the main power in the Nochixtlán valley. Other cities like Huamelulpan declined but were still inhabited. More towns appeared in the valleys and mountains.

Unlike the Zapotecs, who had one capital in Monte Albán, the Mixtecs had many small city-states. These rarely had more than twelve thousand people. Mixtec society was clearly divided into classes. The Mixtec religion also became more established. The worship of rain and lightning, centered on the god Dzahui, was very important.

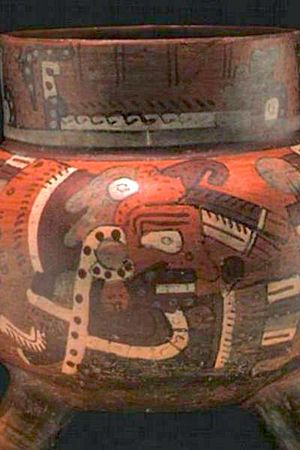

In the Lowland Mixteca, a unique culture called ñuiñe developed. Its main center was Cerro de las Minas. This city began in the Late Preclassic but thrived from the 2nd century AD. Cerro de las Minas had urban features similar to Highland Mixteca cities. It was built around several small plazas. The city was built on terraces, with many stairways. Cerro de las Minas had many stone carvings with a little-known writing system called ñuiñe. This writing was very similar to Zapotec writing from Monte Albán.

Other ñuiñe sites include San Pedro and San Pablo Tequixtepec. Characteristic ñuiñe items include "colossal heads," which are small stone sculptures of human heads. Some are still worshipped today. Urns showing the god of fire and a local version of Dzahui were also common.

During the Classic period, Lowland Mixteca held the main political centers. Cities in Ñuiñe were often built in places that were easy to defend. This suggests there was a lot of conflict. Wars might have been caused by competition between states or rivalry with the Zapotecs. Warfare was also linked to human sacrifices and the ballgame.

Around the 7th century, many Mesoamerican cities faced crises. Teotihuacán and Monte Albán declined. Mixtec states also faced these problems. The ñuiñe culture disappeared, and many important cities were abandoned. However, some cities like Cerro Jazmín and Tilantongo continued to be inhabited.

Mixtec Power and Conquests (Postclassic Period)

The Postclassic period is the best-known time in Mixtec history. This is thanks to old stories written down by the Spanish and the Mixtec codex that survived. In Mesoamerica, this period saw the rise of states focused on warfare. Mixtec cities had been protected by walls for a long time. But in the Postclassic, military activity became even more important. This is shown by the many war-related items and the worship of warrior gods.

By the late 8th century, the ñuiñe style in Lowland Mixteca faded. It was replaced by the style seen in the Mixtec codex. This new artistic style, along with other changes like the worship of the Feathered Serpent, was common across Mesoamerica. The population in La Mixteca grew a lot, especially in Highland Mixteca. The number of towns doubled, and their urban areas expanded significantly. These towns were organized into small, often fighting, states. Each state had a main city that ruled over smaller settlements. This system of power, where a main town (ñuu) ruled over smaller ones (siqui), was always part of Mixtec history. It became even stronger in this period.

From the Postclassic onwards, Mixtecs had more contact with other groups in Oaxaca. This was true even with groups who spoke different languages. The relationship between Mixtecs and Zapotecs became very strong. They had economic and political ties. Many marriages happened between Mixtec and Zapotec noble families. For example, the Codex Nuttall tells of a Mixtec lord marrying a Zapotec noblewoman from Zaachila. Their son, Cocijoeza, later led a combined Mixtec and Zapotec army. They expanded their power into the Central Valleys of Oaxaca.

Many cities in the Oaxaca Valleys show signs of Mixtec presence. This includes Monte Albán itself, where a famous treasure was found in Tomb 7. Some experts believe this shows Mixtec expansion. Others think it means that Mixtec art was used by Zapotec nobles as a sign of prestige. Besides Monte Albán, other cities with Mixtec influence include Mitla, Lambityeco, Yagul, Cuilapan, and Zaachila. Zaachila was the most important Zapotec city until the Mexica conquered it in the 15th century.

Mixtec Expansion to the Coast

Since ancient times, the coast of Oaxaca was home to Zapotec-speaking people. However, the Mixtec language varieties on the coast seem to have separated from the Highland Mixtec languages around the 10th or 11th century AD. This suggests that Mixtecs arrived on the coast later.

A large movement of Mixtecs to coastal towns changed the power balance there. Zapotec and Chatino towns came under the rule of Mixtec nobles. Mixtec chiefdoms on the coast, like Tututepec, had people from many different groups. Tututepec grew rapidly between the 9th and 10th centuries. This growth was linked to Mixtec migration from the highlands. From the 11th century, Tututepec became very important in Mixtec history. It was the first home of Ocho Venado. He was a Mixtec lord who united many states. He controlled a huge area of over 40,000 square kilometers.

The Reign of Ocho Venado

The Mixtec people were usually divided into many small states. But between the 11th and 12th centuries AD, many of these states united under Ocho Venado-Garra de Jaguar (Eight Deer-Jaguar Claw). He was born in Tilantongo in 1063 and died in 1115. He was a very important figure in Mesoamerican history. This was not only because of his power in La Mixteca, but also because of his connections with the Nahua people of central Mexico.

Ocho Venado was not directly in line to rule Tilantongo. He gained fame through military victories. His first battle was in 1071 when he was only eight years old. In 1083, Ocho Venado became the ruler of Tututepec (Yucudzáa) on the Pacific coast. Later, he formed an alliance with the Toltecs. They gave him the title of tecuhtli, a high rank. In 1097, Ocho Venado met with Cuatro Jaguar, an important ally who helped him rise to power.

This alliance helped Ocho Venado become the ruler of Tilantongo after the local leader died. To prevent any challenges, Ocho Venado removed all the other heirs. He became the sole ruler. He conquered Lugar del Bulto de Xipe, where another branch of the royal family lived. In 1101, Ocho Venado defeated the defenders of Lugar del Bulto de Xipe. The sons of the previous rulers were sacrificed. This way, Ocho Venado added the important lordships of Jaltepec and Lugar del Bulto de Xipe to his lands.

During his rule in Tilantongo, Ocho Venado conquered about one hundred Mixtec lordships. He also built a strong network of alliances through his marriages. His wives included noblewomen from other powerful families. His first son, born in 1109, became the heir to Tilantongo. Ocho Venado was sacrificed in 1115. He was defeated by a group of rebel lords who had been under his rule. The rebellion was led by Cuatro Viento, the only son of the previous rulers of Lugar del Bulto de Xipe who had escaped. After Ocho Venado's death, the Mixtec kingdom broke apart into many smaller states. This ended the only period of political unity in Mixtec history.

The Mexica Conquer Mixtec Lands

After Ocho Venado's death, his sons inherited some important lordships. In other Mixtec cities, the old local leaders regained power. The return to many small states meant more conflicts between them. By this time, La Mixteca was one of the richest regions in Mesoamerica. It exported luxury goods like colorful pottery, featherwork, gold jewelry, and carvings. It also traded food from different climate zones.

La Mixteca was located between central Mexico and the Mesoamerican southeast. This made it important for the Triple Alliance (Mexico-Tenochtitlan, Tetzcoco, and Tlacopan). By the late 1400s, much of La Mixteca was under the control of Tenochtitlan. Some major Mixtec cities, like Coixtlahuaca, became centers for collecting tribute for the conquerors. The Mexica's advance into Highland Mixteca helped them control the Central Valleys of Oaxaca. They wanted to control trade routes between the Mexican highlands and the Pacific coast. The Mexica also tried to conquer the Mixtec coast and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. But they were defeated by an alliance of Zapotecs and Mixtecs. A key victory for the Mixtec-Zapotec alliance was at Guiengola. Here, the Mexica were finally defeated by the defenders of the Isthmus.

Spanish Arrival and Conquest

When the Spanish arrived on the coast of Veracruz, different groups reacted in different ways. Some groups, like the Zempoaltecs and Tlaxcaltecs, saw the Spanish as a chance to gain freedom. After Mexico-Tenochtitlan fell in 1521, the Spanish and their native allies attacked other groups, including the Mixtecs.

However, most Mixtecs made agreements with the Spanish. This led to a mix of cultures. The Mixtecs were able to keep many of their traditions, like their language, trade practices, and farming methods. Only a few parts of La Mixteca, like Tututepec, fought against the Spanish conquest.

Mixtec Society

Family and Social Structure

The Mixtecs in the Postclassic period had a family system where individuals could inherit property and titles from both their mother and father. This system also allowed women to hold high positions of power. For example, 951 noblewomen are mentioned in Mixtec codex. In this system, a person would use the same term for their father and all their male uncles. They would also use the same term for their mother and all their aunts. This meant their brothers and the sons of their uncles were called by the same word.

Social Classes in Mixtec Society

Mixtec society was highly structured. These differences did not appear suddenly. They developed as Mixtec society grew, starting around 1600 BC. In the beginning, Mixtec communities had few social differences. Early homes looked similar, and buildings did not have specialized uses. There was little evidence to show clear living areas for the elite.

The Classic period saw the rise of full urban life. The formation of states in La Mixteca led to greater social differences. These differences were supported by beliefs and alliances among the elite. The new ñuiñe style in Lowland Mixteca showed the rulers' desire to highlight their status. Spanish records from colonial times describe several social classes. These can be grouped into:

- yya: The ruler or lord of each Mixtec chiefdom.

- dzayya yya: The Mixtec nobility, who were of the same high rank as the king.

- tay ñuu: The free people.

- tay situndayu: People who worked the land and paid tribute.

- tay sinoquachi and dahasaha: Servants and slaves.

It was very hard to move up the social ladder. Marriages between dzayya yya ensured that nobles kept their power and passed it to their children. Nobles from different Mixtec villages married each other. This created a complex network of alliances. These alliances helped maintain social inequality and order. The free people, tay ñuu, owned themselves and the food they grew on communal land. The tay situndayu had lost control over their work due to war and had to pay tribute to the nobles. The lowest groups had fewer rights. Their lives could be controlled by the nobility.

How Mixtec Politics Worked

One key feature of Mixtec politics was that it was divided into many small states. These states controlled small areas and often fought each other. From the Middle Preclassic period, a system of power appeared among towns within the same state. The importance of each town was shown by the number of large buildings it had. The power of each city or town was not fixed. It changed as different centers competed. For example, Yucuita was replaced by Yucuñudahui as a main power.

The ñuu (meaning "people" or "community" in Mixtec) were the basic unit of political life in the Postclassic. A ñuu could be the head of a state or not. Mixtec states were connected through a network called yuhuitayu (the seat, or mat). This was a political union of two noble families through marriage. Rulers used many strategies to keep their power. One was forming alliances with other noble families. These alliances were often sealed by marriage. Marriages between noble families helped maintain power and order. Mixtec and Zapotec royal families often married each other for centuries.

Mixtec Warfare

The Mixtecs developed their own ways of fighting. They invented weapons and conquered lands. They also defended their territories from invaders. Their conflicts and alliances were mainly between Mixtec cities and Zapotec towns. The most famous Mixtec hero was Ocho Venado. He was a ruler of Tututepec and a great conqueror. His achievements are told in the Codex Nuttal.

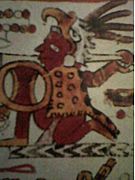

The codex give us a look at the weapons and uniforms the Mixtecs used.

- Long-range attack weapons: Mixtecs used bows and arrows. Their arrow tips were likely made of obsidian or flint. They also used the atlatl, a common weapon across Mesoamerica.

- Close-range attack weapons: For close combat, Mixtecs fought with various clubs and spears. Some spears were similar to the Mexica tepoztopilli but smaller. A common weapon in the codex is a wooden stick bent at a 90-degree angle. It had stone blades (flint or obsidian) on top. This weapon seems to have been special to the Mixtec and Zapotec areas.

- Military clothing: Warriors in the codex wear animal costumes. These include jaguar skins, eagle-headed helmets, and deer skins. Animal uniforms were common in Mesoamerica. The Mexica had famous eagle and jaguar warriors.

Mixtec Daily Life and Economy

Farming and Food

Like other ancient Mesoamerican peoples, the Mixtecs relied on agriculture for their food. The land in La Mixteca was rugged and diverse. This led to different crops being grown in different areas. The most important crop was maize (corn). Other vital foods included different types of beans, chili, and squash. In warmer areas, they grew cotton and cocoa.

One challenge for the Mixtecs was the steep mountains and lack of water. Farming was better in the valleys of Highland Mixteca. To deal with this, they built artificial terraces on mountain slopes. These terraces, called coo yuu, helped create more flat land for farming. They also helped save water. Farmers today say these terraces can produce good corn harvests after a few years. The coo yuu needed constant care. Erosion and farming wore down the soil. In Highland Mixteca, they used caliche from mines to enrich the soil. The Mixtecs also used slash-and-burn farming. They cleared and burned plants to fertilize the soil. This caused a lot of deforestation in the region.

Other Economic Activities

Few animals were domesticated in Mesoamerica. The guajolote (turkey) and the xoloitzcuintle (a type of dog) were two of them. Both were eaten in small amounts. In La Mixteca, they also raised cochineal. This insect lives on the nopal cactus. It was used to make a bright red dye called carmine. Cochineal farming was a main activity until the 1800s, when synthetic dyes appeared.

Besides farming, Mixtecs also hunted, gathered, and fished to get food and other things they needed. The Mixtec region had many different climates. This meant many lordships could produce most of their own food.

The Mixtecs were part of the large Mesoamerican trade network. They traded farm products and cochineal. They also traded valuable materials and manufactured goods. From early times, they produced minerals like magnetite. Pottery from Tayata (Highland Mixteca) was traded with the Olmecs.

Mixtec Culture and Art

Language and Writing

The Mixtecs spoke many different varieties of the Mixtec language before the Spanish arrived. These languages were related but sometimes hard to understand each other. Experts believe that the Proto-Mixtecan language was spoken in the region during the Preclassic period. This language is the source of all Mixtec languages today, as well as Trique. For example, the coastal Mixtec language separated from the highland Mixtec languages around the 10th or 11th century AD. This matches the later settlement of the coast by Mixtecs.

Dominican friars who came to Oaxaca created the first written form of the Mixtec language. Friars Antonio de los Reyes and Francisco de Alvarado wrote the first grammar book for the language spoken in Highland Mixteca. This language, from Yucundaa (Teposcolula), might have been a common language in the region.

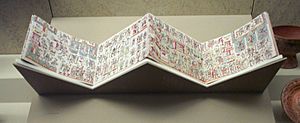

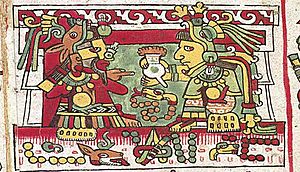

Like other Mesoamerican peoples, the Mixtecs also had written stories. They used a pictographic writing system. We still have ancient examples of this writing, such as the Codex Nuttall, Selden, Vindobonensis, Becker I, and Colombino. Most of these codex are in museums in Europe. These codex were like memory aids. The pictures on their pages could be read aloud as stories by those who knew how to interpret them.

Mixtec Writing System

The Mixtecs, like most Mesoamerican societies, developed a writing system. The earliest signs of writing in the Mixtec area are from Highland Mixteca, in the Late Preclassic period (5th century BC - 1st century AD). In Huamelulpan, some stone carvings with calendar dates were found. These might be the names of ancient Mixtec leaders. However, these carvings use the Zapotec writing system. This system was the origin of later writing systems in central Mesoamerica.

The flourishing of the Lowland Mixteca in the Classic period also brought the development of the ñuiñe script. This script was very similar to the Zapotec script of Monte Albán. Around the 9th century, the Mixtec writing system appeared. This writing is part of a larger artistic style called Mixteca-Puebla style. Mixtec writing is mostly pictographic, meaning it uses pictures. But it also has hieroglyphic and ideographic elements. Mixtec writing helped preserve their beliefs and history. Alfonso Caso proved that the codex in the Mixtec group were made by the Mixtecs. For a long time, people thought they were made by the Mexica or Maya.

Mixtec Religion

The ancient Mixtecs had an animist religion. This means they believed spirits lived in nature. From their written documents, old Spanish records, and archaeological finds, we know their religion shared many features with other Mesoamerican religions. They believed in a main dual force that created the world. They also believed the world had been created and destroyed many times.

According to the Codex Vindobonensis, Uno Venado-Serpiente Jaguar and Uno Venado-Serpiente Puma created the first beings, called ñuhu. These ñuhu helped organize the world. All beings from the first creation turned to stone when the Sun rose. The Sun was worshipped as Yya Ndicahndíí and Taandoco. Some ñuhu hid in caves and survived. The ñuhu represented parts of nature like fire, wind, water, and animals. Because some hid in caves, worshipping mountains and caves was important. Some caves, like those in Chalcatongo, were (and still are) places of pilgrimage. The sanctuary of Nueve Hierba, the Mixtec goddess of death, was in Chalcatongo.

The main god of the Mixtecs was Dzahui, the god of rain and sky water. Rain worship was so important that the Mixtecs called themselves "people of rain," meaning they were chosen by Dzahui. He shares many traits with Tlāloc, worshipped by the Teotihuacan, Toltec, and Mexica peoples. Dzahui's worship in La Mixteca is very old, dating back to the Late Preclassic (between 5th century BC and 2nd century AD).

In the Lowland Mixteca, the ñuiñe society worshipped the old god of fire, Huehuetéotl. This god was worshipped throughout Mesoamerica for a long time. The name Ñuiñe itself means "Hot Land" in Mixtec, reflecting the fire cult. Ñuiñe images of the fire god show him as an old man sitting, with a large brasero (heater) on his head. Some statues from Cerro de las Minas show him holding incense burners. The fire cult existed alongside the rain cult during the ñuiñe period. When this society declined, so did the fire cult.

Human sacrifice was an ancient ritual practice among the Mixtecs. Skulls found at Huamelulpan suggest a tzompantli (skull rack) existed there. Important Mixtec rituals included sacrifices of animals or humans. For example, Ocho Venado ordered the sacrifice of his rivals' descendants. These sacrifices were linked to the worship of Xipe Tótec, the god of fertility.

The religious structure was also hierarchical. High priests were called yaha yahui (Eagle-Fire Serpent). Mixtecs believed yaha yahui could change into animals. They were feared for their power over the supernatural world.

Mixtec Arts

Ancient Mixtec art was closely linked to religion and worship. Many beautiful pieces were made for temples or rituals. Other objects were used by the political and religious elite for daily life. Most known Mixtec art comes from the Postclassic Period (10th-16th centuries). This was a time of great flourishing for La Mixteca. Mixtec society excelled in smaller arts, creating very detailed and precious items. Their architecture and stone sculpture were simpler compared to neighbors like the Zapotecs.

Mixtec architecture was relatively simple. Excavations show remains of buildings that were not very grand. From their codex, we know temples were on pyramid platforms with stairs. Other buildings were around large plazas. Homes for common people were made of less durable materials, like mud walls and palm roofs.

Many Mixtec art pieces are pottery, which has lasted through time. Some of the oldest pieces are from the Middle Preclassic. They show influences from Olmec and Zapotec styles. The ñuiñe style in Lowland Mixteca also shows strong Zapotec and Teotihuacan influences. Representations of the fire god were popular. Other unique ñuiñe pieces are the "colossal heads" found in places like Acatlán. In some mountain areas, ñuiñe pieces are still worshipped today.

The Postclassic Period was the peak of Mixtec pottery. A new artistic style spread in La Mixteca. It was influenced by earlier traditions from Teotihuacan, the Zapotec region, and the Maya area. Mixtec polychrome (multi-colored) pottery was very fine and richly decorated. It was thin, reddish or brown, and had a high-quality burnish that made it look glazed. The surfaces were decorated with themes and colors similar to those in the Mixtec codex. This pottery was for the elite. Some pieces have been found outside the Mixtec region.

Mixtec sculpture also exists from ancient times. Stelae (carved stone slabs) have been found in places like Yucuita. They show Teotihuacan and Zapotec influences. The stelae of Yucuita were simple, large stones with carved dates and names. In ñuiñe sites like Cerro de las Minas, carved lintels adorned building entrances. However, the best Mixtec sculptures are small, finely carved pieces. Mixtecs made beautiful objects from bone, wood, rock crystal, and semi-precious stones like jade and turquoise. These were so exquisite that one expert compared them to "the best Chinese carvings." Many of these items were found in tombs, like Tomb 7 of Monte Albán. This tomb showed the world the amazing artistry of the Mixtec society.

Mixtec Clothing

What Mixtec Women Wore

Mixtec women wore a blanket blouse. It was embroidered around the neck and sleeves. They also wore a full skirt made of poplin with printed flowers. This skirt was decorated with three colored ribbons, symbolizing the three Mixtec regions. On the left side, a bundle of seven bright ribbons shone. Underneath, they wore a blanket sash. A black shawl was used as a girdle, showing if a woman was married or a mother. A scarf around the neck was used to wipe sweat, showing she was hardworking. They wore necklaces of different colored paper beads. For their hair, they braided it and decorated it with four colored ribbons. They also put a red carnation in their hair. To protect their feet, they wore huaraches (sandals) with two white straps.

What Mixtec Men Wore

Mixtec men wore breeches and a blanket shirt. They wore a paliacate (bandana) at their waist and another around their neck. On their shoulder, they carried a wool coton (a type of blanket). They wore a palm hat with a wide brim, in a style called "four stones." They also wore huaraches (sandals) with three white straps.

Metalworking

Metalworking developed late in Mesoamerica. Some experts believe this was a choice by the people, who preferred working with stone. The earliest evidence of metalworking in Mesoamerica is from the end of the Classic period. This technology came from Central and South America, where it developed much earlier. By the time the Spanish arrived, the Tarascans of Michoacán were skilled at working with copper and other metals. They made tools and decorative items.

In the Oaxaca area, the Mixtecs also started using metalworking during the Postclassic period. Copper axes found in the area show that metal was used for tools, not just for decoration. The most famous Mixtec metal pieces are made of gold. Mesoamericans thought gold was the "excrement of the gods." In the Postclassic, it became a symbol of the Sun. So, some of the most beautiful Mixtec gold pieces combine gold with turquoise, which was the most important "solar stone." An example is the Shield of Yanhuitlán.

Gold pieces in Mixtec culture were reserved for rulers. The clothing of Postclassic rulers included many gold items. These were combined with jade, turquoise, feathers, and fine textiles. When the Spanish arrived, many Mixtec gold pieces were melted down into bars. Some were sent to Europe and survived. Archaeologists have found many pieces in archaeological sites throughout La Mixteca. The finds at Zaachila and Tomb 7 of Monte Albán are especially notable. Tomb 7 had the largest number of gold and silver pieces ever found in a single site in Mesoamerica.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Cultura mixteca para niños

In Spanish: Cultura mixteca para niños

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |