Montana Vigilantes facts for kids

The history of vigilante justice in Montana began in 1863. At that time, the area was a remote part of what was called Idaho Territory. Vigilante groups continued their work, sometimes on and off, until Montana became a state in 1889. These groups formed because official law enforcement and courts had little power in the distant mining camps.

In 1863–1864, the Montana Vigilantes were inspired by a group in 1850s California. They wanted to bring order to wild communities near the gold fields of Alder Gulch and Grasshopper Creek. It's thought that over 100 people were killed by "road agent" robbers in late 1863. The Vigilance Committee of Alder Gulch started in December 1863. In just six weeks of 1864, they caught and executed at least 20 road agents from the famous Plummer gang, also known as the "Innocents". When Territorial Judge Hezekiah L. Hosmer arrived in late 1864, official law began, and vigilante actions in that area stopped.

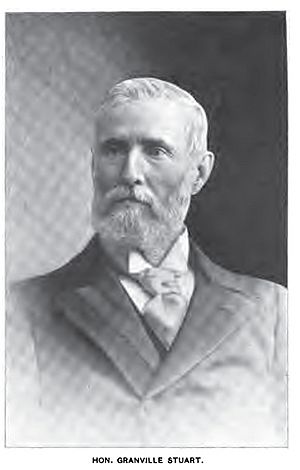

As the gold fields of Alder Gulch and Grasshopper Creek became less active in 1865, miners moved to new areas. These new gold finds were around Last Chance Gulch, which is now Helena, Montana. As crime grew, vigilante justice continued there with the Committee of Safety forming in 1865. Between 1865 and 1870, Helena's vigilantes executed at least 14 suspected criminals. In 1884, ranchers in Central and Eastern Montana also used vigilante justice. They wanted to stop cattle rustlers and horse thieves. The most famous group there was "Stuart's Stranglers", started by Granville Stuart near the Musselshell River. As more official law enforcement arrived, vigilantism slowly faded away.

People have written about and told stories of vigilantism in Montana for over a century. The first book published in Montana was Thomas J. Dimsdale's The Vigilantes of Montana in 1866. He wrote it from newspaper articles he published in 1865. Historians still debate if the vigilantes acted for the good of their communities. They wonder if the lack of a working justice system at the time meant the vigilantes did what they thought was best.

Contents

Gold Rush Towns: Bannack and Virginia City

On July 28, 1862, gold was found along Grasshopper Creek. This was a remote part of eastern Idaho Territory. This discovery led to the town of Bannack. Bannack was a gold rush boomtown. It was also the first capital of Montana Territory for a short time after the territory was created in 1864.

Less than a year later, on May 26, 1863, gold was found along Alder Gulch. This creek was about 70 miles east of Bannack. The Alder Gulch discovery became one of the biggest placer gold fields in the western U.S. The mining towns of Virginia City and Nevada City, Montana quickly grew in Alder Gulch. By the end of 1863, thousands of miners lived there.

These new towns often lacked the justice systems found in more settled parts of the territory. In 1863, gold was the main form of money. It was worth $20.67 per ounce, set by the U.S. Government. Most buying and selling in mining towns used gold nuggets or dust. The more gold someone had, the richer they were.

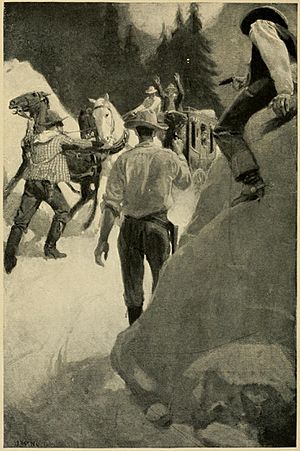

In the early years, there was no safe way to move gold out of the region. Gold was transported by horseback or slow wagons and stagecoaches. These traveled on a few trails and rough roads. Some roads led south and west to Salt Lake City and San Francisco. Others went east to Minnesota.

Roads leading to Alder Gulch included the Bozeman and Bridger Trails from the east. There was also the Mullan Road from the west. From Fort Benton, Montana, at the start of the Missouri River navigation, and the Corinne Road from Corinne, Utah, were other routes. A 70-mile stage road connected Alder Gulch with Bannack. Stagecoaches stopped at ranches to water horses and feed passengers. One ranch, Rattlesnake Ranch, was owned by Bill Bunton and Frank Parish. They were later executed by vigilantes as road agents.

Robbers and the Plummer Gang

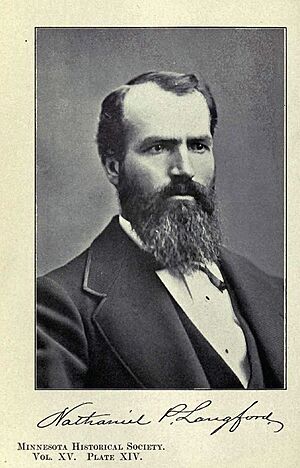

In a region with lots of gold, unsafe travel, and little law, travelers were easy targets for robbers. By late 1863, thefts and murders on the roads around Alder Gulch were common. Writers like Thomas Dimsdale and Nathaniel P. Langford estimated that at least 102 travelers were killed by robbers in the fall of 1863. Many more left the area and were never seen again.

Locals began to suspect that these crimes were done by one group of outlaws. They were known as "road agents" and were thought to be led by Bannack sheriff Henry Plummer. The gang was called the Innocents because their secret password was I am innocent.

Miners' Courts Didn't Work

Before Montana Territory was created in May 1864, the only courts in Bannack and Virginia City were informal miners' courts. These courts were meant to settle arguments about mining claims. But when a big crime like murder happened, they often couldn't solve it well enough for the community.

There aren't many stories about early courts in Alder Gulch. This is probably because they were informal and didn't last long. John X. Beidler remembered a murder trial in Virginia City in his writings. It was in the fall of 1863 and was about the murder of J.W. Dillingham. The trial was held outside because everyone in town took part. In the end, all three accused men were set free.

One man, Charley Forbes, was freed after a moving speech about his mother. The other two, Buck Stinson and Haze Lyons, were found guilty. They were supposed to be the first men executed in what would become Montana. But at their public hanging, friends of Stinson and Lyons convinced the crowd to vote again. Beidler said people voted by walking uphill to hang them or downhill not to. This vote was rejected. Then, four men formed two "gates," and people voted by walking through the "hang" gate or the "no hang" gate. Beidler claimed friends of the accused walked through the "no hang" gate many times, possibly letting two murderers go free.

On December 19–21, 1863, a public trial was held for George Ives. He was suspected of murdering Nicholas Tiebolt, a young immigrant. Hundreds of miners watched the three-day outdoor trial. Wilbur F. Sanders was the prosecutor. Ives was found guilty and executed on December 21, 1863. Sanders later became Montana's first U.S. Senator. Even though Ives was executed, many people were frustrated by the slow process that could be easily tricked. Thomas Dimsdale, who wrote the first book about the Montana Vigilantes, described this feeling:

Another powerful reason for bad actions is that the civil law has no power in such cases. No matter how strong the proof, if the criminal is liked in the community, 'Not Guilty' is almost certain to be the decision, even with the judge and prosecutor trying their best.

The Vigilance Committee Forms

On December 23, 1863, two days after the Ives trial, a group of five Virginia City residents started the Vigilance Committee of Alder Gulch. Wilbur F. Sanders led the group, which also included Major Alvin W. Brockie, John Nye, Captain Nick D. Wall, and Paris Pfouts. The committee was set up like the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance from California, which some of the organizers knew about.

The first members signed an oath:

We the undersigned joining together to arrest thieves and murderers and get back stolen property, promise on our honor to keep secrets, follow the laws of right, and never leave each other or our idea of justice. So help us God, this 23rd of December 1863.

Paris Pfouts was chosen as the committee's president. They wrote and agreed upon a detailed set of rules. These rules created positions like president, executive officer, secretary, and captains. The most important rule said:

Members must join a company. If they learn of a crime, they must tell their Captain. The Captain will gather his company to investigate. If the company thinks the person should be punished, the Captain will arrest the criminal and report to the Chief. The Chief will call a meeting of the Executive Committee, and their decision will be final. The only punishment this Committee will give is death.

Important Members

The vigilance committee started small and secret in Virginia City. But news of it spread, and more people joined. Because it was a secret group, we don't know the exact number of members. However, many members became important figures in Montana's history.

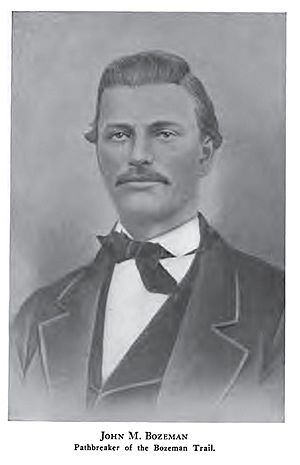

Some members included Wilbur Sanders (who became Montana's first U.S. Senator), Sidney Edgerton (Montana Territory's first Governor), Nelson Story (famous for a cattle drive and a Bozeman merchant), John Bozeman (founder of Bozeman, Montana), Nathaniel P. Langford (first Yellowstone National Park superintendent), James Stuart (brother of Granville Stuart), Tom Cover (a gold prospector), and Thomas Dimsdale (newspaper editor and author of The Vigilantes of Montana).

Because the group was secret, it's hard to know for sure if an execution was done by the committee or another group of citizens. In the months after the Ives trial, many suspected road agents were executed. One famous person executed was Henry Plummer, the sheriff of Bannack. Many believed he was the leader of the road agents. The Montana Vigilantes executed men based only on the confessions of others who were about to be executed.

John X. Beidler and Thomas Dimsdale wrote the most complete stories of the early Alder Gulch Vigilantes. But they didn't share much about the secret trials. Historian Frederick Allen believes that between 1863 and 1865, 15 to 35 people were killed by the Alder Gulch vigilantes.

Vigilante Actions

Over about six weeks, from December 1863 to February 1864, vigilante groups found, arrested, and executed suspected members of the Plummer road agent gang. This happened in Bannack, Virginia City, and Hellgate, Montana.

Bannack

Soon after forming, the Vigilance Committee sent a group to find Aleck Carter, "Whiskey Bill" Graves, and Bill Bunton. These men were known to be with George Ives. The group was led by Captain James Williams, who had investigated the Nicolas Tiebolt murder. Near Rattlesnake Ranch, they found "Erastus Red" Yeager and George Brown, both suspected road agents.

On the way back to Virginia City, Yeager confessed everything. He named most of the road agents in Plummer's gang, including Henry Plummer. After getting his confession, Yeager and Brown were found guilty and quickly executed from a cottonwood tree.

On January 6, 1864, "Dutch John" Wagner, a road agent wounded in a robbery, was caught. Vigilantes took Wagner to Bannack, where he was executed on January 11, 1864. By this time, Yeager's confession had made vigilantes act against Plummer and his main helpers, deputies Buck Stinson and Ned Ray. Plummer, Stinson, and Ray were arrested on the morning of January 10, 1864, and quickly executed.

On January 11, 1864, "Greaser Joe" Pizanthia, another road agent on Yeager's list, was found in his cabin near Bannack. A gunfight started, and one vigilante, George Copley, was killed. Pizanthia's cabin was hit by three shells from a small cannon belonging to Sidney Edgerton. Pizanthia was badly wounded and was shot and killed as he was pulled from the cabin's ruins.

Virginia City

After Wagner's execution on January 11, 1864, the vigilantes, mostly from Virginia City, went back there. They wanted to deal with the rest of the Plummer gang's road agents. On the evening of January 13, 1864, the Vigilance Committee voted to arrest and hang six road agents. These men were believed to be living in Virginia City: Frank Parish, Boone Helm, Hayes Lyons, Jack Gallagher, George "Clubfoot" Lane, and Bill Hunter.

On the morning of January 14, 1864, five of the six road agents were found in town and arrested. They were all quickly executed on Wallace Street. Bill Hunter escaped capture in Virginia City. But he was later arrested at a cabin on the Gallatin River and executed on February 3, 1864.

After the hangings on January 14, 1864, the vigilante groups left Virginia City. They searched for the remaining road agents on Yeager's list. The first one found was Steve Marshland, hiding in a cabin on the Big Hole River. He was executed on January 16, 1864. A group led by Captain Williams found Bill Bunton at his Cottonwood Ranch and executed him on January 18, 1864.

Hell Gate

After the Bunton execution, the vigilante groups gathered again. They rode 90 miles to Hell Gate, Montana. They believed more road agents were hiding there. In Hell Gate, Captain William's vigilante group found and arrested Cyrus Skinner, Aleck Carter, and John Cooper.

A vigilante trial for Skinner and Carter was held in a dry goods store on January 24, 1864. Both men were found guilty and executed outside the store. Later that day, Cooper was tried, found guilty, and executed. On January 25, 1864, the vigilantes found Bob Zachary in a cabin outside Hell Gate. They found George Shears in another cabin in the Bitterroot Valley. Zachary was brought to Hell Gate and executed. Shears was executed outside the cabin where he was caught.

As the vigilante groups were leaving Hell Gate to return to Virginia City, they heard that "Whiskey Bill" Graves was at Fort Owen, Montana. Three vigilantes found and arrested him on January 26, 1864. He was executed the same day.

Forced to Leave and Escapes

Another method used by the vigilantes was to banish people from the territory. We don't know how many men were warned to leave or face execution. Alexander Toponce, a merchant in Bannack, thought many were banished. He wrote in his autobiography:

I don't think they [the vigilantes] made any mistake in hanging anybody. The only mistake they made was about fifty percent of those whom they merely banished should have been hung instead, as quite a number of these men were finally hung.

Some road agents from Plummer's gang or on Yeager's list escaped vigilante justice. They did this by fleeing the territory. Some of these men were Augustus "Gad" Moore, Billy Terwilliger, William Mitchell, Harvey Meade, "Rattlesnake Dick", "Cherokee Bob", Tex Caldwell, Jeff Perkins, Samuel Bunton, "Irwin of the Big Hole", William Moore, and Charles Reeves.

Official Law Arrives

In the summer of 1864, Hezekiah L. Hosmer, a lawyer from Ohio, was appointed as the first Chief Justice of Montana Territory. He arrived in Montana in October 1864. Before the first meeting of the Territorial Legislature in December 1864, Judge Hosmer announced something important. He said that Common Law would be the main criminal and civil law. Idaho's Territorial Law would be used for court procedures.

On December 5, 1864, Judge Hosmer held a public Grand Jury session in Virginia City. He boldly announced that the vigilantes had done their job. From that day forward, any actions taken by vigilantes on their own would be considered criminal acts.

Helena Vigilantism (1865–1870)

On July 14, 1864, four prospectors found gold in a small creek. They named it "Last Chance Gulch." As news spread, miners, including many from Alder Gulch and Bannack, moved to Last Chance Gulch. This is how the town of Helena, Montana, was founded. By mid-1865, many important Alder Gulch vigilantes, like Wilbur Sanders and John X. Beidler, had moved to Helena.

When the territory was formed, three court districts were set up. The First District, with Judge Hosmer, included Bannack and Virginia City. The Third District covered the towns around Helena. From July 1864 to August 1865, the only justice system in Helena was the miners' court. The Third District didn't get its first chief judge until August 1865, when Judge Lyman Munson arrived.

On June 8, 1865, John Keene shot and killed Harry Slater in a Helena saloon. Keene gave himself up to Sheriff George Wood and admitted what he did. A two-day trial followed. Some jury members were known vigilantes from Alder Gulch. Since there was no official judge, Stephan Reynolds, a respected Helena citizen, oversaw the trial. The jury found Keene guilty, and he was executed just outside town. Even though Keene's trial wasn't considered vigilantism, the Helena community felt they needed a more reliable way to keep law and order, just like Alder Gulch had.

Committee of Safety in Helena

Vigilante justice in Helena was similar to Alder Gulch. Right after Keene's hanging, leading Helena citizens formed the Helena Committee of Safety. This group was like the Vigilance Committee of Alder Gulch. We don't have records of its members or rules. But Nathaniel Langford, who was asked to lead the group (but declined), wrote about it. He said that crimes like horse stealing, murder, and highway robbery would be punished by death.

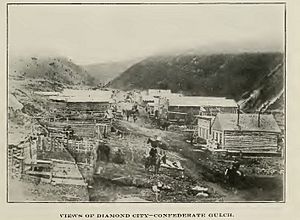

In July 1865, the Helena vigilantes caught Jack Silvie in Diamond City, Montana. They accused him of various robberies. Before he was executed, Silvie confessed to being a member of the Virginia City road agents. He also admitted to at least a dozen murders in the territory.

Soon after Judge Lyman Munson arrived in Helena, he called a grand jury on August 12, 1865. However, unlike Judge Hosmer, Munson didn't say anything about vigilantism. He didn't threaten vigilantes with charges if they continued. The vigilantes showed little respect for Munson's court. They went on to carry out at least 14 more executions without official trials. One was in January 1870, when Chinese worker Ah Chow was executed for shooting a white miner. No Helena vigilante was ever charged by Munson's grand jury for their actions.

The last execution by the Helena vigilantes happened on April 27, 1870. Joseph Wilson and Arthur Compton were executed from the "Old Hangman's Tree." They were punished for robbery and attempted murder. This double execution was photographed. The widely shared image helped to reduce public support for vigilantism.

A Time of Peace

By the 1870s, Montana was experiencing a period that historian Frederic Allen called a "sort of pax vigilanticus." This means a time of peace brought by the vigilantes' reputation for quick executions. Allen also said it was linked to the discovery of gold in the Black Hills of the Dakota Territory. This drew many miners and camp followers out of Montana. This reduced the number of people who were more likely to commit crimes.

Ranchers Take Action

By the 1870s, cattle and horse ranching was a big and successful business in Montana. Cattle and horses were valuable. They were often stolen by thieves. After 1879, the threat from Indian wars lessened on the Montana plains. So, ranches and open range cattle ranching moved east into Central and Eastern Montana. The DHS ranch, owned by Samuel Hauser, Andrew Davis, and Granville Stuart, started in 1879. It was in the Musselshell region and became one of Montana's largest open range ranches.

The first group of ranchers in Montana formed in Virginia City in 1873. They met to talk about branding standards and how to deal with rustling. They also wanted to influence the territorial government to pass laws that helped the cattle industry. This group didn't last, but it led to other groups forming later. In 1878, the Montana Stock Association of Lewis and Clark County was organized. A key member, Ross Deegan, wrote about the need for unofficial action if the government didn't pass laws to protect cattle:

Will [our lawmakers] give us protection, or shall we be forced against our wishes to become judges and executors of what we think is a fair punishment for breaking property rights?

In July 1879, a Territorial Stock Association was formed. This led to many smaller county groups across Montana. By 1883, the value of cattle in Montana was over $25 million. Yearly losses from rustling were more than three percent. By the summer of 1884, cattle ranchers started using vigilantism to deal with rustlers. The first recorded hanging happened at Fort Maginnis on July 3, 1884. Reese Anderson, a DHS ranch foreman, and other ranch hands executed Sam McKenzie for stealing horses.

Stuart's Stranglers

The hanging of Sam McKenzie and other unofficial justice in July 1884 made many thieves and rustlers leave the territory. However, a large group of horse thieves still operated in the Musselshell region. With the quiet approval of the rancher groups, Granville Stuart set up a small spy network. He gathered forces to go after the thieves.

His group included many of Stuart's ranch hands and detectives hired by rancher associations. They were known as "Stuart's Stranglers." These vigilantes found dozens of stolen horses. They also caused the deaths of at least 20 thieves in July 1884, by hanging, shootings, or fire. The last hanging happened on August 1, 1884.

In July 1884, Theodore Roosevelt, who later became the 26th President of the United States, had a cattle ranch in Medora, North Dakota. His ranch was also suffering from rustling. Both Roosevelt and Marquis de Mores offered to help the Stranglers. But Stuart said no, to avoid too much attention. After this, stock detectives, hired by the rancher groups, took over enforcing stock laws and stopping rustling.

There was some public anger about the killings. But none of Stuart's Stranglers were ever put on trial. Newspaper articles in the region praised their efforts. Granville Stuart's actions were widely approved. He was elected as the first president of the Montana Stockgrower's Association in late July 1884.

The 3-7-77 Symbol

The numbers 3-7-77 have long been linked to Montana vigilantes. What they mean is not clear. Many ideas have been suggested, but none are proven. Some say it refers to the size of a grave. Others say it was the amount of time a bad person had to leave town. There are also ideas about Masonic symbols or how the group was set up. Some think it was just copied from groups in Colorado and California.

Even though it's linked to the Alder Gulch vigilantes, historical facts don't support this. The first time the symbol was definitely used in a vigilante situation was in November 1879. It was mentioned in a Helena newspaper article. A study in 1914 said it was simply used as part of a meeting notice. The symbol was put on the uniform patch of the Montana Highway Patrol (MHP) in 1956. MHP leader Alex Stephenson designed the patch. He said, "we chose the symbol to keep alive the memory of this first people's police force."

Stories and Books About the Vigilantes

The first written story about the vigilantes was Thomas Dimsdale's Vigilantes of Montana. It first appeared as articles in the Montana Post newspaper in 1865. This was Virginia City's and Montana's first newspaper. Dimsdale was a member of the Alder Gulch Vigilance Committee and the editor of the Montana Post. His early accounts are often used as sources. The book version, published in 1866, was the first book printed in Montana Territory. It has been reprinted many times.

Dimsdale's book is valuable because it is exactly what it claims to be. Truth is stranger than fiction, and no grand story of the old west has ever sounded as real. In The Vigilantes, we have the facts before they become fiction, the true moment in history before rumors and tales turn it into a legend.

John X. Beidler, who helped enforce the vigilante rules in Alder Gulch and Helena, wrote about his experiences in his personal journals. These journals were not published until 1957, long after his death. Helen F. Sanders, the daughter-in-law of Wilbur Sanders, finally got them published.

Nathaniel P. Langford, also a vigilante member, published Vigilante Days and Ways-Pioneers of the Rockies in 1893. In a 1912 speech, historian Olin Wheeler praised the Alder Gulch vigilantes.

...Under the vigilantes, criminals were hung or banished, crime was quickly punished, lives and property were safe, and society was saved from chaos. Some of the best citizens in the territory were Vigilantes... Mr. Langford's book, Vigilante Days and Ways, gives facts and reasons that justify the vigilante methods. It is fair, honest, strong, and convincing. These men deserve honor and praise, not criticism, for what they did.

Another account, published in 1982, came from former Montana Supreme Court Justice Lew L. Callaway. His son edited Montana's Righteous Hangmen: The Vigilantes in Action. This book came from Callaway's connection with vigilante Captain James William in the late 1800s. Callaway wrote many stories that give more personal details about how the vigilantes worked.

Even though some vigilante actions were criticized, people generally agreed with their purpose. They believed the vigilantes helped bring law and order to the growing territory. Mark C. Dillon's book Montana Vigilantes 1863–1870 Gold, Guns and Gallows (2013) says that given the lawless times, the vigilantes did what they thought was best. He argues that judging them by today's standards of justice is difficult.

Justice Dillon's book is the first to look at western vigilante history through the lens of law. It examines the role lawyers and judges played in bringing back a trusted justice system. Historian Paul R. Wylie, who reviewed Dillon's manuscript, believes the book "will be the best work on the Montana Vigilantes." Wylie describes the book as "careful, informative, judicial, well-written and very readable." He says, "there has never been a work in the area quite like this."

In 2004, Frederick Allen, a journalist and historian, published A Decent and Orderly Lynching: The Montana Vigilantes. This book is seen as a balanced, up-to-date account. It confirms the reasons and methods of the early vigilantes. It also talks about how people started to dislike vigilantism in the late 1860s. Other general Montana history books also cover the vigilante period.

Some books published in the late 1900s say that the Alder Gulch vigilantes were part of a political plot. They argue that the victims didn't get fair trials. These books, like Hanging the Sheriff-A Biography of Henry Plummer (1987, 1999) and Vigilante Victims: Montana's 1864 Hanging Spree (1991), have been criticized by Montana historians.

In Hanging the Sheriff, R. E. Mather and F. E. Boswell have completely changed the picture of Sheriff Henry Plummer. They have challenged the usual reasons for the Montana vigilantes of 1863–64. The authors disagree with the vigilante supporters who said Plummer's rule of terror made a vigilance committee necessary. First, law was already in place at Bannack through the miners' court, Plummer's election, and Judge Edgerton's arrival. Second, Plummer's supposed leadership of the road agents was based on an unproven accusation.

This is a "revisionist" history of the Vigilante movement. It claims the road agents were victims of a plot between two groups fighting for power. It ignores the cooperation between Pfouts, a strong Confederate, and Sanders, who was against slavery, in leading the Vigilantes. It also ignores that Jack Gallagher supported the Union, while Boone Helm died shouting, "Hoorah for Jeff Davis!"

Another writer, John C. Fazio, believes the Vigilance Committee of Alder Gulch was more about national politics than fighting criminals. He thinks Sidney Edgerton and Wilbur Sanders were used by Abraham Lincoln and other Union supporters. They wanted to get rid of Southerners and Confederate sympathizers in the Montana gold fields. Novelist Carol Buchanan has disagreed with his views.

Henry Plummer's Mock Trial

On May 7, 1993, the Twin Bridges, Montana public schools held a mock trial for Henry Plummer. It took place at the Madison County courthouse in Virginia City. The trial got national media attention. Adults and students acted out the events using stories from Dimsdale, Beidler, and Langford. After a six-hour trial, the jury of four men and eight women was tied, 6-6. The student playing Henry Plummer was told he was "free."

Because of the mock trial's fame, some academics who believed Plummer was innocent asked the Montana Board of Pardons and Parole to pardon him. Many famous historians supported this. However, the board denied the pardon. They said they didn't have the power to act because Plummer had never actually been found guilty of a crime in Montana.

In Popular Culture

- Ernest Haycox's 1942 novel Alder Gulch shows Bannack Sheriff Henry Plummer as a cold and cruel murderer and thief.

- John Dehner played Henry Plummer in an episode of the 1950s western TV series, Stories of the Century.

- Montana Territory is a 1952 Western film. It's a classic western with bandits, a bad sheriff [Plummer], and a hero who falls for a beautiful woman.

- An episode of the TV series Overland Trail, The Montana Vigilantes, aired in April 1960.

- In "Two for the Gallows" (April 11, 1961) of NBC's Laramie, Slim Sherman (John Smith) is hired to take a "Professor Landfield" (Donald Woods) into the Badlands to find gold. But Landfield is actually Morgan Bennett, a former Plummer gang member who escaped from prison.

- The Missouri Breaks is a 1976 American western action film. It shows rustling and revenge in eastern Montana in the 1880s.

- The Scottish folk band, The David Latto Band, wrote a song about Henry Plummer called 'Plummer's Song'. It was released on their 2012 album. The song is from the view of a Bannack community member who had doubts about Plummer's crimes.

Images for kids

-

Ponderosa pine alleged to be a "hanging tree" in Jefferson County, Montana, near Clancy.

| Anna J. Cooper |

| Mary McLeod Bethune |

| Lillie Mae Bradford |