Portland stone facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Portland Stone FormationStratigraphic range: Tithonian |

|

|---|---|

Portland stone quarry on the Isle of Portland

|

|

| Type | Geological formation |

| Unit of | Portland Group |

| Sub-units | Dorset: Portland Chert Member, Portland Freestone Member

Vale of Wardour: Tisbury Member, Wockley Member, Chilmark Member Vale of Pewsey: No formal subdivision |

| Underlies | Lulworth Formation |

| Overlies | Portland Sand Formation |

| Thickness | up to 38 metres (120 ft) in Dorset |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Limestone |

| Other | Siltstone, Sandstone |

| Location | |

| Region | England |

| Country | |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Isle of Portland |

| Location | Clay Ope, West Weare Cliff |

| Thickness at type section | 25 metres |

Portland stone is a special type of limestone rock. It's officially called the Portland Stone Formation. This stone formed a very long time ago, during the Tithonian age of the Late Jurassic period.

You can find and dig out (or quarry) this stone on the Isle of Portland in Dorset, England. The quarries are places where layers of white-grey limestone are dug out. These layers are sometimes separated by layers of a hard, glassy rock called chert.

Portland stone has been used a lot for building in the British Isles. Many important public buildings in London, like St Paul's Cathedral and Buckingham Palace, are made from it. Portland stone is also sent to many other countries. For example, it was used for the United Nations headquarters in New York City.

Contents

How Portland Stone Formed

Portland stone was created in a warm, shallow, sub-tropical sea. This sea was probably close to land, as we sometimes find fossilized driftwood in the stone.

When the sun warmed the seawater, it released carbon dioxide (CO2) gas into the air. This allowed calcium and bicarbonate in the water to combine and form calcium carbonate (CaCO3). Calcium carbonate is the main part of most limestones.

Tiny crystals of calcium carbonate, called calcite, built up on the seafloor. They formed a soft, muddy material called lime mud. Small bits of sand or shell pieces acted like tiny seeds. As they rolled around in the mud, layers of calcite built up around them. This created small, round balls, less than half a millimeter wide.

These tiny balls are called "ooids" or "ooliths," which means "egg-shaped stones." Over time, billions of these ooids became partly stuck together by more calcite. This process is called "lithification." It formed the oolitic limestone we know as Portland stone.

Portland stone is hard enough to resist bad weather, but also soft enough for builders to cut and carve easily. This is why it's a favorite stone for important buildings and monuments. On the Mohs scale of mineral hardness, Portland stone measures 3.5.

History of Using Portland Stone

People have been digging stone on Portland since the time of the Romans. By the 1300s, it was being shipped to London. Digging for stone as an industry really started in the early 1600s. The stone was sent to London for Inigo Jones's Banqueting House.

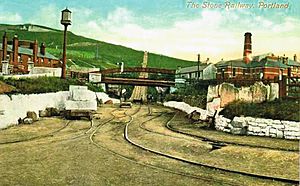

A big boost for the quarries came when Christopher Wren chose Portland stone for the new St Paul's Cathedral. This made Portland stone London's top choice for building. A railway connected the island to the rest of the country in 1865.

Today, companies like Albion Stone PLC and Portland Stone Firms Ltd continue to quarry and mine Portland stone.

Quarries and Mines

Portland stone is taken from the ground in two main ways: quarrying and mining.

Quarries

Quarries are open pits where stone is dug from the surface.

- Jordans Mine is part of the Inmosthay Quarry. It has been worked since the late 1800s.

- Bowers Quarry has been used since the late 1700s. It was the first place where Portland stone was mined underground.

- Coombefield Quarry near Southwell has been an open-pit quarry for 80 years. It will soon become a holiday park.

- Perryfield Quarry is actively being quarried. It has enough stone for over 20 more years.

- Broadcroft Quarry was used for St Paul's Cathedral. It also has over 20 years of stone left.

After quarries are used up, they are restored. The Portland Sculpture and Quarry Trust works to preserve the knowledge of stone and the landscape. They are based at Tout Quarry, a non-working quarry.

Mining

Mining means digging for stone underground. This method has less impact on the environment and local people.

- Jordans Mine now uses mining instead of quarrying. This helps protect the local cricket club and the environment. It is the biggest mine on Portland.

- Bowers Mine now extracts all its stone underground.

- Stonehills Mine is a completely new mine that started in 2015. It is expected to have stone for 50 years.

Mining uses special machines with diamond blades and water-filled bags (hydro-bags) to cut and move the stone. This avoids noisy and dusty blasting.

How Stone is Mined

In Portland, mining uses a "room and pillar" method. This means they dig out "rooms" of stone, leaving "pillars" of rock to support the roof.

Machines with abrasive chain cutters make slots in the stone. Then, a flat steel pillow is put into a cut and slowly filled with water. This gently breaks off the stone blocks without stressing them. This method is more expensive than blasting, but it saves more stone and is much better for the environment. It creates less noise and dust, which helps wildlife and local communities.

Famous Portland Stone Buildings

Portland stone has been used for building since Roman times. Roman stone coffins found locally show how skilled their builders were.

The oldest known building made with Portland stone is Rufus Castle on Portland. It was first built around 1080.

Portland stone was used for:

- The Palace of Westminster in 1347.

- The Tower of London in 1349.

- The first stone London Bridge in 1350.

- Exeter Cathedral and Christchurch Priory in the 1300s.

Its excellent qualities have made it popular with builders and architects ever since.

- The East side of Buckingham Palace, the home of King Charles III, was covered with Portland stone in 1854 and again in 1913.

- The Victoria Memorial (unveiled in 1911) is also made of it.

Inigo Jones used Portland stone for the Banqueting Hall in Whitehall in 1620. Sir Christopher Wren used almost one million cubic feet of it to rebuild St. Paul's Cathedral and many other churches after the Great Fire of London in 1666. All this stone was brought by sailing barges from Portland to London.

Other famous London buildings made of Portland stone include:

- The British Museum (1753)

- Somerset House (1792)

- The Bank of England

- The National Gallery

- Tower Bridge (which also uses Cornish granite)

Recently, Portland stone has been used for Chelsea Barracks and Green Park tube station in London.

In Manchester, Portland stone was often used in the 1930s. Buildings like 100 King Street (1935) and Manchester Central Library (1934) have Portland stone exteriors.

Two of Liverpool's famous buildings, the Cunard Building and the Port of Liverpool Building, are covered in Portland stone.

The Nottingham Council House (1929) and public buildings in Cardiff's civic center also use Portland stone. Architect Charles Holden used it for many of his designs in the 1920s and 1930s, like Senate House.

After the Second World War (1939–1945), many bombed cities in England, like Plymouth and Coventry, were rebuilt using lots of Portland stone.

Many buildings at the University of Leeds are covered in Portland stone. The Ashmolean Museum in Oxford also used a lot of Portland stone in its renovation.

Portland stone is used all over the world. Examples include the UN building in New York and the Auckland War Memorial Museum. Many important buildings in Dublin, Ireland, like City Hall (1779) and the General Post Office (1818), are made of it.

The BBC Broadcasting House in London, built recently, also uses Portland stone.

The International Union of Geological Sciences has named Portland stone a Global Heritage Stone Resource. This means it's a very important stone worldwide.

Memorials Made of Portland Stone

After the First World War, Sir Edwin Lutyens used Portland stone to build The Cenotaph in London. This monument, built in 1920, remembers the millions of people who died in wars.

The RAF Bomber Command Memorial in London's Green Park also uses Portland stone. It honors the 55,573 aircrew members who died during the Second World War.

The gravestones for British soldiers killed in the First and Second World Wars are made from Portland stone.

The Armed Forces Memorial in Staffordshire, England, is also made of Portland stone. It was finished in 2007 and lists the names of over 16,000 British service members killed since the Second World War.

Why Portland Stone is Sometimes Replaced

Portland stone is known for its high quality, but it can be quite expensive. For example, when the British Museum's central court was being redone, they chose to use a similar but cheaper limestone from France called Anstrude Roche Claire instead of Portland stone.

Portland Cement

The name "Portland cement" was created by Joseph Aspdin in 1824. He made a strong building material by burning a mix of limestone and clay. He named it "Portland cement" because he thought it looked like the famous Portland building stone.

See also

In Spanish: Piedra de Pórtland para niños

In Spanish: Piedra de Pórtland para niños

- List of decorative stones

- List of types of limestone