Robert Campbell (frontiersman) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Robert Campbell

|

|

|---|---|

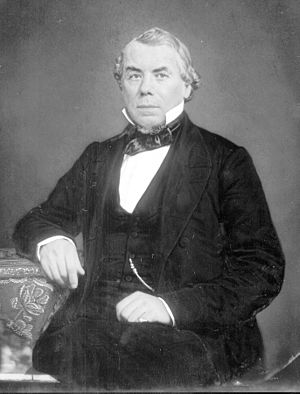

Photograph of Campbell circa 1860

|

|

| Born | February 12, 1804 |

| Died | October 16, 1879 (aged 75) |

| Known for | Exploration of Rocky Mountains, Head of two Missouri Banks, Owner of Steamboats, Real Estate Mogul in St. Louis, Missouri, and Kansas City, Missouri |

| Signature | |

Robert Campbell (February 12, 1804 – October 16, 1879) was an Irish immigrant who became a famous American explorer, fur trader, and successful businessman. His home in St. Louis is now a museum, the Campbell House Museum, where you can learn about his life.

Contents

Robert Campbell's Early Life

Robert Campbell was born on February 12, 1804, in a house called Aughalane in County Tyrone, which is now in Northern Ireland. His family was of Scottish descent. The house was built by his ancestor, Hugh Campbell, in 1786. Today, Aughalane is preserved at the Ulster American Folk Park.

As the youngest child from his father's second marriage, Robert wouldn't inherit much. This led him to follow his older brother, Hugh, to America. He arrived in Philadelphia on June 27, 1822. In 1823, he met John O'Fallon, an Irish immigrant who lived in St. Louis. Robert got a job as an assistant clerk at Council Bluffs. He spent a tough winter at Bellevue on the Missouri River. Robert had lung problems as a child, and the cold winter made them worse. He then moved to O'Fallon's store in St. Louis. A doctor there told him to go to the Rocky Mountains for his health, saying it had helped others.

First Adventures in the West (1825–1829)

On November 1, 1825, Robert Campbell joined an expedition heading to the Rocky Mountains. This group was led by fur trader Jedediah S. Smith. They had money from William H. Ashley and his Rocky Mountain Fur Company. The group included about sixty men, many of whom were experienced explorers. Because Robert was educated and skilled, Smith asked him to be the expedition's clerk.

Robert's first trip into the American West was challenging. He spent a difficult winter with the Pawnee tribe. After the spring thaw, the group traveled north to a traders' meeting called a Rocky Mountain Rendezvous in Cache Valley, located in modern Utah and southern Idaho. There, Ashley sold his share of the business. The expedition then split up. Robert traveled with the group led by David Edward Jackson and William Sublette. He later wrote about hunting along the Gallatin River and trapping near the headwaters of the Columbia River. They spent the winter of 1826-27 together again in Cache Valley.

In late 1827, Robert led a small group into Flathead territory. They were attacked by Native Americans and lost some men. Robert and two others left to find the main group. They traveled slowly due to bad weather and reached a Hudson's Bay Company camp in February 1828. After leaving a message, Robert returned to his men for the rest of the winter.

In the spring of 1828, the group trapped along Clark's Fork and Bear Lake. They were attacked by Blackfeet on their way to the summer rendezvous but still brought in their beaver furs. After trading, Robert joined Jim Bridger on a trapping trip to Crow country in northeastern Wyoming. They spent the winter in the Wind River area. In the spring of 1829, Robert decided to go back to Ireland to see his family. He was trusted with forty-five packs of beaver furs by the group. He arrived in St. Louis in late August. He sold the furs for over $22,000 and earned more than $3,000 for his work.

Battles and Forts (1832–1835)

When Robert Campbell returned to the West, William Sublette asked him to become business partners. Sublette even let Robert buy his own goods for the trading rendezvous. This way, Robert could use the money from selling his goods to officially join the business. Robert and William Sublette's new company also got a special license to carry 450 gallons of valuable whiskey to the next rendezvous.

The successful fur trapping season in 1832 ended with a famous fight called the Battle of Pierre's Hole. As the traders were leaving the rendezvous, a group of Gros Ventres Native Americans encountered a trapping group. This started a big battle. The Gros Ventres quickly built defenses from logs. Trappers arrived to help, and a day-long fight began. Several trappers and many Gros Ventres were killed. The Native Americans managed to escape during the night. Robert, who was writing a letter to his brother, joined the fight. Both Sublette and Robert led a charge against the Native American defenses. Robert helped Sublette when he was shot in the arm. The Battle of Pierre's Hole was later written about in a book by Washington Irving.

Sublette and Robert then decided to challenge John Jacob Astor's American Fur Company. They did this by building forts right next to Astor's. In 1833, Robert built Fort William near the mouth of the Yellowstone River. This fort mainly traded buffalo robes with local Native American tribes like the Assiniboine, Cree, and Gros Ventres. Fort William and Astor's nearby fort, Fort Union, competed for the loyalty of the chiefs by offering gifts and good deals. Robert was a good diplomat and managed to get the loyalty of a Cree chief. Their company was very successful, and Astor's company eventually paid them to leave the area.

The fur trade was quickly ending. So, Sublette and Campbell decided to close their last outpost. They chose to focus on trading buffalo robes and other goods instead. This was a smart move because in 1835, buffalo robes sold for more money than beaver furs for the first time. By the end of the decade, robes were worth $6 each, while beaver furs had dropped to $2.50. This was because the beaver population had decreased, and silk became more popular than beaver fur for hats.

Growing Businesses (1836–1845)

St. Louis was a natural place for Sublette and Campbell to open their business. It was the center of the fur trade. In September 1836, they bought a brick building for $12,823. Here, they sold dry goods, often allowing customers to pay later. Robert was very good with money. He was fair but firm, always making sure debts were paid to him, and always paying his own debts. He didn't use the harsh business practices that became common later.

Campbell and Sublette bought a lot of land in the upper Mississippi valley. They also worked as loan agents for banks and invested in insurance and hotel companies. All these investments sometimes put them close to going broke because it was hard to collect money from people who owed them. Despite these problems, Robert Campbell became more important in society. In December 1839, he was chosen by the state government to be on the board of directors for the Missouri State Bank. Even though he didn't always have a lot of cash, he was financially stable enough to buy a large piece of land in what is now downtown Kansas City.

In 1842, the "Sublette and Campbell" partnership ended. They decided not to renew their agreement. However, they remained good friends. Their store was simply divided in half by a wall. An economic crisis in the 1840s almost ruined Robert. But a good friend, Sir William Drummond Stewart, a Scottish Lord, sent him money just in time. Sublette became very sick and died in 1845, which was a great loss for Robert.

Expanding His Empire (1845–1860)

Robert Campbell was very successful in the late 1840s. In 1846, he was elected President of the State Bank of Missouri. He helped the bank grow its deposits and the value of its money. Robert's leadership of the bank was very successful. Bank notes signed by him were accepted all over the country. This job also paid him $3,000 a year. Robert also found a new business partner, William Campbell (no relation), and they formed the company "R. and W. Campbell" in 1848. This new company invested in railroads and steamboats. They also successfully placed their allies as suppliers in several forts in the West.

Robert Campbell was known for understanding the West. So, when the Mexican–American War started in 1846, Robert was made a state militia colonel. His job was to gather and equip 400 volunteer cavalry soldiers. The United States' victory allowed Campbell to expand his business into the American Southwest along the El Paso Trail. Campbell also supplied John C. Fremont's exploration expedition in 1843. His connections to famous people in the West went beyond military matters. Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, a well-known Jesuit missionary, often worked with Campbell. Because of his experience in the West, the U.S. government asked Campbell to help negotiate the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851. This fort had actually been owned by Campbell and Sublette before, under the name Fort William (not the same as the 1833 Fort William on the Yellowstone River).

Two big problems in 1849 threatened St. Louis's success. First, a cholera sickness spread through the city. Then, in July, a fire started along the waterfront and quickly spread. The fire destroyed $6.1 million worth of property, including Campbell's store. Robert Campbell recovered well from this. He used the insurance money to pay off old debts from "Sublette and Campbell." He also bought a new location for R. & W. Campbell. St. Louis continued to grow. This growth led Robert to new business opportunities. The buffalo robe trade on the upper Missouri River continued to make money. Western traders trusted Campbell's credit more than the U.S. government's, because Robert was seen as more reliable. Steamboats also became more important. In 1858, Campbell bought a steamboat called the "A. B. Chambers" for $833.32. This boat was the first one piloted by Samuel Clemens, who later became famous as Mark Twain. Investing in the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers was risky. The "A. B. Chambers" sank by 1860. Even then, Robert made a profit from the $9,480 insurance claim.

The Civil War Years

Living in Missouri during the American Civil War meant balancing between those who supported the Southern states and those who supported the Union. As the important election of 1860 neared, Robert thought the extreme Southern supporters were just noisy. When states started leaving the Union, Campbell quickly said he was a "Conditional Unionist." This meant he supported the Union but also believed in the right to own enslaved people. He supported the Crittenden Compromise of 1861, which tried to stop the war from starting. Campbell was important enough to be elected President of the Conditional Unionists at a meeting in St. Louis on January 12, 1861. The group voted to support slavery as a constitutional right and asked the government not to use force during the crisis.

While Robert supported the right to own enslaved people, he had freed his last enslaved person several years before. In 1857, Robert freed Eliza and her two sons. This was apparently because his wife, Virginia, didn't like the practice of slavery. So, Robert had a complex view, common at the time, seeing slavery as legal but not morally right. After the first crisis in 1861, Campbell mostly stayed out of politics during the war. He focused on his businesses instead. He supplied troops for most of the war, including a large contract to pay soldiers in New Mexico. The war disrupted traffic on the Mississippi River, slowing business. Even when the river reopened, the government sometimes took Robert's ships for their own use. On one trip, his ship, the Robert Campbell, was destroyed by someone who supported the Confederacy.

When Robert did get involved in politics, it was usually to oppose the strict policies of the Republican party. Robert supported his neighbor, General William Harney, who commanded Union forces in Missouri. He also supported Harney's friend and successor, General John Frémont. Robert also tried to help friends who were arrested under strict military law. These actions were risky. Some people in St. Louis doubted Robert and his brother Hugh's loyalty. This was partly because both Campbells had married women from the South. Despite the strong political power of the Republicans, both Campbells kept their good reputations after the war. Robert probably didn't like the loyalty oaths required by the government, but he signed his in September 1862. This helped him stay in the highest levels of society.

Later Years and Legacy

Robert's businesses continued to grow even more in his later life. In 1871, his business empire reached El Paso, Texas, where he bought land at an auction. Unfortunately, this land got tied up in court cases, causing problems for Robert for the rest of his life. More successful ventures included gold mining. Miners would send Robert gold dust. He would then ship it east to be turned into coins. Robert shipped about 497 pounds of gold dust between 1867 and 1870, worth over $102,000.

In 1866, Robert also bought the Southern Hotel, making it the most important part of his real estate business. The hotel had taken 15 years to build and hadn't done very well for years. After he bought it, the hotel had a big renovation that cost $60,000. Robert improved almost every room. The St. Louis Republican newspaper said it was the best hotel in the city. Sadly, Robert had installed a steam heating system in the hotel. Just after midnight on April 11, 1877, this system started a fire that quickly burned down the entire six-story building. Every fire engine in the city helped try to save the 150 staff and guests. Fourteen guests died, and the damage was estimated at $1.5 million. One firefighter was praised for his bravery. Robert was very sad about the hotel's destruction. He said that the $492,000 insurance check was at least $100,000 less than the building's true value. He planned to rebuild on the site but died before he could make formal plans.

In the late 1860s and 1870s, the Campbell family was very influential in politics and society. General Ulysses Grant became President in 1868, and the Campbell family had close ties with the Grant family. The Campbells hosted Grant and other guests several times, and Robert also visited the White House. Robert's connections to Grant, along with his vast experience with Native American tribes in the West, led to his appointment in 1869 to the Board of Indian Commissioners. Men on this board were supposed to be honest and wealthy enough not to be tempted by corruption. Their goal was to help stop corruption. Campbell traveled through the West, meeting various tribes, including the Ute, Cherokee, and the Oglala chief Red Cloud. The Commissioners eventually suggested that Native Americans should become more like white society. They encouraged ending tribal self-governance and more cultural retraining. They also said that the high level of corruption in the Indian Bureau was a big problem. Since the Commission couldn't make progress against the corruption, every member, including Robert, resigned in protest in May 1874.

Robert's health got much worse in the 1870s. His lung problems, which had never fully gone away, continued to bother him. He had a very bad attack during a dinner party for General William Sherman, which kept Robert in bed for a month. To try and get better, the Campbells traveled to Saratoga Springs. Despite these efforts, his health continued to decline. On October 16, 1879, Robert had trouble breathing and was in severe pain. He died that evening and was buried in Bellefontaine Cemetery on October 19. His funeral was so large that not everyone could fit inside the house.

Robert Campbell's Family Life

Robert Campbell met his future wife, Virginia Campbell, in Philadelphia in 1835. Virginia's cousin was married to Robert's older brother, Hugh. When they met, Robert was not well, and Virginia helped take care of him. He quickly fell in love with her. They wrote many letters to each other during a long courtship. Their age difference (Robert was 31, Virginia was 13) and the distance between them made it hard. Their families and friends also didn't approve.

In 1838, Robert asked Virginia to marry him, and she said yes. Robert happily asked her mother, Lucy Ann Winston Kyle, for permission. But her mother refused, saying Virginia was too young at 16 to be married. However, she did let Virginia and Robert keep writing letters.

In the summer of 1839, Virginia suddenly asked to end their engagement. Robert, though heartbroken, agreed. He wrote to her, "You have ruined the happiness through life of a heart that loved only you." Robert's feelings for her never changed. Virginia's mother became less fond of Virginia's new admirers. In December 1840, Mrs. Kyle showed she preferred Robert. Days later, Robert wrote a letter to Virginia, showing he still loved her deeply. These letters worked, and Virginia accepted his proposal again. Robert and Virginia were married in North Carolina on February 25, 1841.

Robert and Virginia first lived in a suite at the Planter's House hotel in St. Louis. This was the city's best hotel. Their family soon began to grow. Their first son, James Alexander, was born on May 14, 1842. Hugh was born in 1843, but he died of pneumonia before his first birthday. They had several more children, and like many families at the time, they reused names, so they had a second son named Hugh. As the family grew, the Campbells started renting a house in 1843. The owners of the house couldn't pay their loans, so the land was taken and put up for sale in 1847. Robert was worried about his home, so he bought the property directly.

Despite having a larger house, the Campbells continued to face sadness. Two years later, in 1849, a cholera epidemic swept through St. Louis. The disease was worst in July, killing many people. Among those who died was the Campbells' first son, James, on June 18. The second Hugh also almost died but survived.

Many people in the city wanted to leave the unhealthy downtown area. This led to the development of Lucas Place in the 1850s. Robert bought a house at 20 Lucas Place on November 8, 1854, paying $13,677 to live in this fancy, exclusive neighborhood. Even with the move, the Campbells' health problems didn't stop. In total, the Campbells had 13 children, but only three lived to adulthood. These three children, Hugh, Hazlett, and James, never married. They owned and lived in their father's house for the rest of their lives.

Other family members also joined the Campbells. Lucy Kyle, Virginia's mother, moved in with them in 1856. Robert's brother Hugh and his wife moved to St. Louis in 1859. Other relatives, including Virginia's sister and some of Robert's Irish family, also stayed at the house for different periods. Robert's brother Hugh then became his unofficial business partner.

Robert died on October 16, 1879, and Virginia died in 1882. They are buried with their children in Bellefontaine Cemetery. The three surviving children never married and stayed at the Campbell House until the last son died in 1938. The home is now preserved as the Campbell House Museum, with its original furniture and decorations.

Robert Campbell's Writings

During his expeditions and explorations of the Rocky Mountains, Robert Campbell wrote many letters to his brother between 1832 and 1836. These letters were published in a Philadelphia newspaper called The National Atlas and Tuesday Morning Mail in late 1836. The letters described his travels in the Rockies, what the Native Americans he met looked like, and their customs. He even wrote about the deaths of some of his friends. These letters were first printed again in 1955 as The Rocky Mountain letters of Robert Campbell.

Images for kids

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |