Salt industry in Syracuse, New York facts for kids

The salt industry has a long history in and around Syracuse, New York. In 1654, Jesuit missionaries were the first to report salty brine springs near the southern end of "Salt Lake," now known as Onondaga Lake. Later, the Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1784) and the "Onondaga Salt Springs Reservation" helped start commercial salt production. This happened from the late 1700s to the early 1900s.

The salt springs stretched for almost nine miles around Onondaga Lake. They started in Salina and went through Geddes and Liverpool. Most of the salt used in the United States in the 1800s came from Syracuse. Even today, Syracuse is sometimes called "the Salt City."

| Top - 0-9 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z |

How Salt Formed in Syracuse

Ancient Seas and Mountains

Hundreds of millions of years ago, thick layers of rock formed under the Syracuse area. Two large landmasses collided on the East Coast of North America. This created a huge mountain range. To the west, a big, shallow inland sea formed.

Over millions of years, rain and runoff slowly wore down the mountains. Sediment, like mud, piled up in the sea. This mud eventually hardened into thick layers of rock called shale.

The northern edge of this ancient sea was near Tully, about five miles south of Syracuse. As the shallow parts of the sea dried up, they left behind layers of salt. These salts included calcium carbonate (calcite), calcium sulfate (gypsum), and sodium chloride (halite), which is common table salt.

The Ice Age and Salt Springs

During the Ice Age, huge glaciers moved across the land. They carved and reshaped the ground, which was made of limestone, shale, and salt deposits. When the glaciers melted, they left behind deposits. These created underground water systems called aquifers.

These aquifers connected the salt deposits near Tully to the salt springs at Onondaga Lake. This connection allowed salty water, or brine, to flow to the surface.

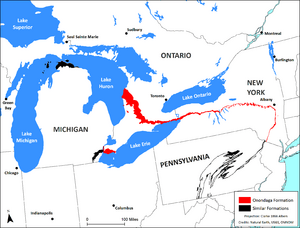

The salt found in Syracuse is part of the Onondaga salt-group. This group stretches from the Hudson Valley all the way to Wisconsin and Iowa.

Salt can come from three main sources:

- Rock salt (fossil salt)

- Sea water

- Salt brine from springs, lakes, or wells.

The brine from Onondaga Lake could be used to make two types of salt. Coarse salt was made using the sun's heat (solar evaporation). Refined salt was made by boiling the brine.

Early Discoveries and Interest

Jesuit Missionaries Find Salt

The salt springs of Onondaga Lake were known to the Jesuit missionaries. In the early 1500s, some Spaniards traveled from Florida. They wanted to see a "mysterious white substance" covering the ground.

On August 5, 1654, Father Simon Le Moyne, a French Jesuit, arrived at the Onondaga village. He drank from a spring that the Onondagas thought was bad because of an evil spirit. But the French saw the salt's true value.

We tested the water of a spring, which the Indians are afraid to drink, saying that it is inhabited by a demon, which makes it foul. I found the fountain of salt water, from which we evaporated a little salt as natural as that from the sea, some of which we shall carry to Quebec. - Father Simon Le Moyne from his diary in 1654

Dutch and British Interest

By 1660, the Dutch in New Amsterdam (now New York City) and Fort Orange (now Albany) heard that "salt grew out of the ground." But they didn't believe it at first.

The British became interested in the land around Onondaga Lake in the early 1700s. They became friends with the Onondagas by giving them guns, which were very valuable.

In 1751, Sir William Johnson, a British agent, heard that the French wanted to build a military post near the salt springs. He talked to the Onondagas. He suggested they give him rights to Onondaga Lake and a two-mile strip of land around it. The Onondagas agreed and were paid £350. However, this agreement was later declared invalid in 1788.

Presbyterian Missionaries and the State

In 1776, Presbyterian missionary Samuel Kirkland from Scotland became interested in the Syracuse "salt lands." He told General Philip Schuyler about them. Schuyler suggested that the springs could be "improved to advantage" if someone knew how to boil salt. But nothing happened for 11 years.

Salt Production Begins

Onondaga Salt Springs Reservation

The Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1784) gave land around Onondaga Lake from the Onondaga Nation to local salt makers. The agreement said the land would be used to make salt "for the common use of everyone." Because of this treaty, the State of New York named the area the Onondaga Salt Springs Reservation.

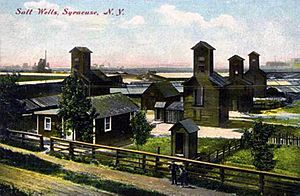

The salt works were shaped like a crescent around the southeastern shore of Onondaga Lake. They covered almost 1,000 acres. By 1872, the reservation was about 750 acres. The salt reservation was roughly nine miles long and eleven miles wide.

Early Settlers and Hardship

The Onondaga Indians owned the springs until after the Revolutionary War. Some early European settlers made small amounts of salt for themselves. They would boil the salt in "open kettles" over a fire. In 1774, two enslaved people were reported boiling brine in brass kettles and selling salt to the Onondaga Indians.

In 1788, early Syracuse pioneers Asa Danforth and Comfort Tyler were the first to arrive. By 1792, six families lived and worked in an area called Salt Point, later known as Salina.

Life in the swampy area was very difficult. The salt springs were in swamps and bogs for much of the warm year. Many people got Malaria and suffered from fevers and nausea. In 1793, out of 33 people, 30 were sick. The next year, 23 people died. Those who survived traded salt for food during the winter.

Commercial Salt Making

As more people saw the "ease, profits and other advantages" of making salt, bigger operations started. Asa Danforth and Comfort Tyler were the first to make salt commercially in 1789. Danforth carried a five-gallon kettle from his home to the reservation. He boiled about 30 pounds of salt in nine hours.

Tyler helped him set up poles and hang the kettle over a fire. After making enough salt, they would hide their tools. They continued this until 1790.

By 1798, salt houses were built from logs. A group called The Federal Company built a large building for 32 kettles. Water was pumped by hand from a shallow well into wooden reservoirs.

Before the Erie Canal, transportation was hard. Oxen pulled salt on stone-boats through marshy land.

Salt Strength and Dilution

The brine from the reservation was very salty. In 1743, one gallon of water could be boiled down to one pound of salt. A tool called a salometer measured salt saturation. In the 1800s, the brine was often 74% to 78% saturated with salt.

In the early 1800s, more brine was pumped from deep underground. When the outlet of Onondaga Lake was lowered in 1822 for the Erie Canal, the water level around the lake dropped. This caused the salt springs to flow faster. Over many years, fresh water from other aquifers mixed with the deep brine, making it less salty. Less concentrated brine took longer to evaporate and produced less salt.

By 1875, new wells helped increase the brine's strength. But shallow wells still became weaker when pumped too much. New York State was worried about the cost of fuel to make salt from weaker brine. They faced strong competition from Michigan and Canada. The State drilled new deep wells to get stronger brine. This helped reduce the cost of making salt.

State Control and Growth

State Regulation of Salt

By the late 1770s, many people were making salt without permission. New York State wanted to stop this and prevent any company from controlling all the salt production. The State also wanted a steady income.

In 1795, the Onondagas gave their common rights to the land around Onondaga Lake to the State. The first law to regulate salt production was passed on April 1, 1797.

The New York State Legislature set aside a one-mile-wide strip of land around the northern half of the lake as the Onondaga Salt Springs Reservation. Laws were passed to control how salt was made (boiling and solar evaporation), stored, and sold. A tax of four cents for every bushel of salt was also set. The State also set the price of salt and required it to be stored in government warehouses for a fee. They also checked the quality and quantity of all salt produced.

Salt lots were leased for many years. In 1797, the State divided the land into salt lots, store lots, and pasture lots. Private companies could dig wells and make salt by paying tax to the State. The reservation grew to 15,000 acres. This industry helped New York State for the next 100 years.

The Governor appointed a superintendent for the salt springs. This person was not allowed to have any interest in the salt business. The superintendent and their helpers would dig wells, pump water, and distribute it to the factories. They also inspected the salt, weighed it, branded packages, and collected taxes.

Some salt makers didn't like state involvement. Many tried to smuggle salt to avoid paying taxes. But the superintendent had strong power to check every bushel produced.

The State of New York owned and managed the Onondaga Salt Spring Reservation from 1797 to 1908. They leased land to people to build salt-making facilities. The State also owned the wells, pumps, pipelines, and storage areas.

From Salt Point to Salina

In 1794, James Geddes settled in Geddes, on the west shore of Onondaga Lake. By 1796, he built the first salt factory there. The Onondaga Indians claimed the salt springs west of the lake. But they accepted Geddes into their tribe and let him continue making salt. More settlers came, and small groups of log houses were built around the salt works.

In 1797, Geddes was hired by the State to survey the Onondaga Salt Springs Reservation and plan the first road in Salt Point. In 1798, Salt Point became the village of Salina. Geddes also designed the streets for the Surveyor-General, Simeon DeWitt.

How Salt Was Made

Boiling Salt (Fine Salt)

The Onondaga Indians and early European traders made salt by boiling. This was called fine salt. Boiling was popular because it was fast and could be done all year. It was also easy and cheap for individuals to start. Many early salt miners were just passing through. They boiled salt to trade for other goods.

The methods were simple. A kettle was hung over a fire, and the water boiled away. Wet salt was left behind, then dried. Wood was plentiful and used for fires.

By 1791, about 8,000 bushels of salt were made each year. Each bushel weighed 56 pounds. An early salt boiler might make 600 bushels a year.

Boiling Blocks

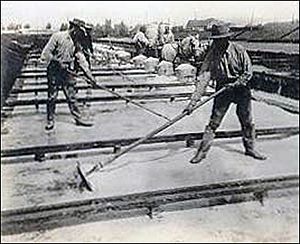

As salt making grew, larger factories were built. These were called boiling blocks or salt blocks. They had large iron kettles set into stone, arranged in rows inside long shed-like buildings. Workers in boiling blocks worked in 90°F heat and high humidity, twelve hours a day, seven days a week, from April to November.

The kettles were round, made of cast-iron, and about three feet wide. They were placed in walls of brick or limestone, 50 to 100 in a row. A long flue carried heat from a furnace under the kettles to a tall chimney. Workers shoveled coal into the furnace.

Large kettles held 150 gallons and were closest to the fire. Smaller kettles, about 100 gallons, were further away where the heat was less intense. The air was so thick with vapor that workers looked "phantom-like."

Boiling blocks had up to 80 kettles and ran 24 hours a day. They used hundreds of cords of wood daily, then 11 to 12 tons of coal. Each kettle produced salt three times every 24 hours. Impurities like iron oxides and calcium chloride were removed. Salt crystals were scooped out and drained in baskets. A boiling block could make three to four bushels in five hours.

The brine contained calcium chloride, magnesium, and gypsum. When boiled, these settled to the bottom and were removed as a chalky paste called bittern. This waste was drained away.

Some kettles were heated by steam jackets, which kept the temperature even and produced consistent salt quality.

Another method was the "pan process." Large wrought-iron pans, 24 feet wide and 100 feet long, were used. They were heated by flues from fires. The salt was drained on sloping wooden platforms. The brine was cleaned with milk of lime, similar to the kettle process.

The plants ran continuously for about 14 days. The State required salt to be stored for 14 days to cure. Then it was packed into barrels and inspected by the State.

By 1872, there were 316 fine salt blocks and four large mills. The industry employed 5,000 men and paid over $86,000 in taxes to New York State each year.

In 1797, almost 26,000 bushels of salt were produced. By 1872, this number grew to nearly nine million bushels.

Erie Canal and Salt

From the start, rivers and lakes were used to transport salt. But these routes were difficult. Syracuse salt makers, especially Joshua Forman and James Geddes, strongly supported the Erie Canal project.

The Erie Canal opened in 1825. This greatly increased salt sales because transportation became cheaper and easier. Also, canal shipping made New York State farms switch from growing wheat to raising pigs, and curing pork needed a lot of salt.

After the War of 1812, it was hard to get salt from other countries. So, commercial salt production became very important in Syracuse. The Erie Canal allowed Syracuse salt to be shipped to Chicago and beyond through the Great Lakes quickly and cheaply.

By 1837, salt makers suggested raising the salt tax to help pay off canal debt. The tax was raised, then lowered again later.

Salt production increased rapidly with lower shipping costs. It reached a high point of eight million bushels annually during the Civil War. Syracuse became an important canal port.

By 1893, the salt industry was declining. But the Onondaga Salt Springs Reservation had contributed over two million dollars to build the Erie Canal and Barge Canal. People in Syracuse called the Erie Canal "the ditch that salt built."

Salt Potatoes

Salt potatoes started in Syracuse. They were a big part of a salt worker's daily food. In the 1800s, Irish salt miners brought small, unpeeled potatoes to work. At lunchtime, they boiled them in the salty brine.

By the early 1900s, salt potatoes were a favorite in Central New York. A local businessman, John Hinerwadel, started serving them at his clambakes. He later packaged bags of potatoes with a box of salt, calling them "Hinerwadel's Famous Original Salt Potatoes." You can still find this brand today.

Salt and the Civil War

During the Civil War, salt production in Syracuse was vital for the North's salt supply. At the same time, the North controlled salt mines in Virginia and Pennsylvania. This meant Southerners couldn't buy salt. The lack of salt is thought to be one reason the South lost the war. Salt workers in Syracuse were so important that they were excused from jury duty and military service in the mid-1860s.

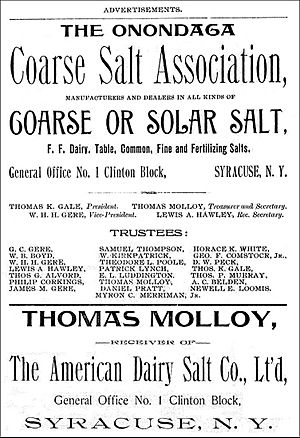

Solar Evaporation (Coarse Salt)

By the 1820s, local wood for fuel was running out. The cost of importing coal from Pennsylvania was making salt production very expensive. Many salt producers switched to the solar evaporation method by the mid-1800s.

The idea for solar salt production came from Judge Joshua Forman in 1821. He is considered the founder of Syracuse. Forman and others visited salt works in Massachusetts. They learned how to build similar works in Syracuse.

Two companies were formed: the Onondaga Salt Company and The Syracuse Salt Company. They started by clearing a swampy area to build the first salt vats. They also built a large reservoir, pumps, and aqueducts to get more water.

Building the vats used a lot of lumber. By 1841, 220,247 barrels of solar salt were produced annually. This number kept growing for the next 40 years.

Solar evaporation, or solar salt production, needed more concentrated brine than the local springs provided. Shallow wells were dug to find stronger brine. Solar evaporation was slower, and wet weather could delay it. However, it was cost-effective. By 1864, it became the main way to produce salt. Large areas along the lake shore were used for salt fields. One drawback was that solar salt could only be made during warmer months, from April to early November.

The solar method had three steps:

- Brine was pumped into large vats in deep rooms. Here, impurities like iron oxides settled. This took two weeks.

- The brine then moved to salt rooms (or lime rooms). In shallow vats, gypsum settled, and the brine evaporated further. This took seven days. The vats looked like "hundreds of mirrors" under the sun.

- The concentrated brine went into shallow wooden trays called covers. These had movable roofs to protect the brine from rain and at night. A loud bell would ring if it rained, and people would rush to cover the vats.

After seven days, coarse salt crystals appeared. The salt was harvested and moved to State storage warehouses. It was drained for 14 days before being packed. Salt was "harvested" about three times a season.

By 1900, there were over 43,000 salt covers, covering a huge area. In a good season, three to four million bushels of salt were produced. Solar salt operations stopped during colder months, from December to March. The average "working" year was only 70 days long.

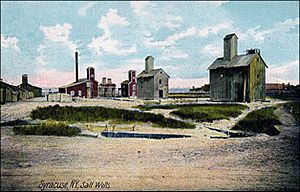

Salt Wells and Pumps

Early salt brine came from natural springs and shallow wells. In 1806, the first "deep well" was dug, 30 feet deep. Hand pumps brought up about 40 gallons of brine per minute.

Starting in 1838, the State drilled deep wells to find the source of the brine. But none of them pinpointed the exact source.

By 1878, wells were 300 to 450 feet deep. When the drill hit the salt water, it rose to within 18 feet of the surface. Small steam-powered pumps brought it the rest of the way. By 1878, 38 wells were in use, producing seven million bushels annually.

The wells were narrow and deep, 8 to 10 inches wide. They were lined with iron pipes to prevent contamination from surface water. Lengths of pipe were screwed together and forced down until they reached the brine.

The State ran water and steam-powered pump rooms in four areas: Geddes, Liverpool, Salina, and Syracuse. These pumps forced brine from the lake into tall reservoirs.

The brine was pumped using an endless wire rope chain powered by an engine. When it reached the surface, it looked a bit cloudy. This was from clay, sand, and small bubbles of carbon dioxide. The brine also contained ferrous carbonate. As carbon dioxide escaped, the ferrous salt absorbed oxygen, and ferric oxide separated as a yellowish-red cloudiness, which settled, leaving clear brine.

Brine was pumped into small settling tanks, then channeled through wooden pipes to a central distribution tank. This tank was higher than the boiling blocks, so gravity could control the flow. If the central tank was too low, the brine was pumped into a large reservoir on top of an 80-foot tower on high ground. From there, it flowed by gravity to the factories.

The main pump was powered by a 22-foot overshot water wheel. A back-up steam pump was ready in case of breakdown. The pump ran from April to early December, as the wheel couldn't operate when the canal froze. Boiled salt could only be made as long as the water wheel turned.

In the 1890s, a new system used compressed air to pump brine from deep wells. This method produced 150-160 gallons of brine per minute from 100-foot-deep wells.

Log Pipes

The forests around Syracuse were cleared to provide fuel for boiling salt and lumber for homes and boats. The pepperidge tree (Nyssa sylvatica), also known as tupelo, was especially good for making "brine-pipes." These trees were so valuable and in such high demand that they are now almost gone within 10 miles of the city.

The pipes were made from hollowed-out logs, often called elm logs. One log end was inserted into another and bound with "iron ribbons." There were 50 miles of these pipes across the reservation. They were always laid above ground and were very durable.

Packaging Salt

Both solar salt and block salt were coarse when they left the reservation. Solar salt was used for preserving pork. Much of the block salt was refined into table salt.

The finished salt was washed to remove remaining impurities like chlorides of calcium, magnesium, and gypsum. It was placed in a shallow tube with water and turned by corkscrew-like shafts until clean. The waste was sold to farmers for $1.50 a ton.

After washing, the salt was dried in long, iron cylinders that revolved over furnaces. It became as dry and hot as desert sand. Then, an endless chain of small buckets carried it upstairs for grinding. Salt for dairy use was ground between granite rollers. Salt for table use went through a regular flour mill.

Young women scooped the salt into small cotton bags and sewed them quickly. The bags were then packed into barrels and shipped to market.

In 1876, an analysis showed that Syracuse dairy salt was "superior to all others" and had fewer impurities. This helped overcome a long-held belief that Onondaga salt was impure.

Decline and Legacy

Western Competition and Decline

After the Civil War, the salt industry began to decline. By 1876, there was strong competition from Michigan and Canada. The State tried to improve the brine to make Onondaga salt more competitive.

They drilled new deep wells to increase the brine's saltiness. This reduced the cost of fuel needed to make salt. Chemists also spent years trying to find more efficient ways to evaporate salt, but most experiments were too expensive to be widely used.

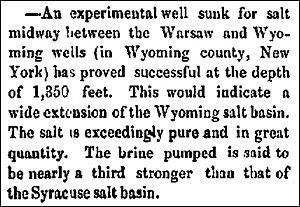

In November 1882, an experimental well in Wyoming County, New York, found a large salt deposit. This salt was very pure and plentiful. The brine was almost 33% stronger than Syracuse's brine. These new deposits were part of the same geological formation as Syracuse's salt.

In March 1885, a 20-foot-thick vein of salt was found near Phelps by an oil company drilling for petroleum. Soon after, a company was formed to manage these mines. New salt reserves were also found out west in Wyoming and Utah.

End of Production

By 1900, the salt industry in Syracuse faced increasing costs and competition from western producers. The salt in Onondaga Lake was also becoming weaker. These factors led to the end of the salt industry in Syracuse.

In 1908, New York State sold its pipelines, pumps, and reservoirs to private companies. The Salt Springs Superintendent was let go in 1914. After the State stopped production, private companies continued, but some land was still government-owned.

The end of the salt industry went largely unnoticed by city residents. Syracuse's economy was booming. Its central location, railroads, canals, access to raw materials like gypsum, brine, and limestone, and a large workforce attracted many different industries. The land used for salt works became more valuable for factories, pushing the old industry out.

By 1920, most salt was used to pack fish and in ceramic production. It was also used to de-ice railroad and trolley tracks in winter. Chemical companies, like the Solvay Process Company, also needed salt brine.

In 1922, a wind storm destroyed much of the remaining salt yards. Some repairs were made, but the industry struggled. In August 1926, the last nine salt workers drew the final batch of brine, and the salt industry closed. The Onondaga Coarse Salt Company, the last manufacturer, had been in business for 125 years.

In 1938, large deposits of natural Trona (sodium carbonate) were found in Wyoming. This made the Solvay process (used by Solvay Process Company) too expensive. The Solvay Process Company plant closed in 1985.

Even though salt mining ended, salty water still flows from 1,000 feet below the Tully valley to the salt springs around Onondaga Lake.

The "Salt City" Legacy

The rapid growth of the salt industry in the 1700s and 1800s gave Syracuse its nickname, "the Salt City." From 1797 to 1917, the Onondaga Salt Springs Reservation produced over 11.5 million tons of salt. The Solvay Process Company also extracted over 96 million tons of salt from the Tully valley.

Even though salt production is over, Syracuse still honors the industry. Streets like Salina Street and Solar Street, Salt Springs Road, and the town of Salina, New York, are named after it. There's also a neighborhood in Syracuse called Salt Springs.

Salt Museum and Parks

In the early 1900s, the abandoned Onondaga Salt Springs Reservation became a dumping ground. But during the Great Depression, Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt gave the State land to Onondaga County. Funding from the Work relief program helped the county turn the area into Long Branch Park in the early 1930s.

As part of this project, the Salt Museum was built around a remaining boiling block chimney. The museum opened in 1933 and is still open today. It is operated by Onondaga County Parks Department and closes during the winter.

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |