Snake facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Snakes |

|

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Infraorders | |

|

|

|

|

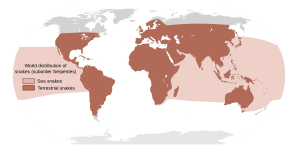

| Approximate world distribution of snakes, all species |

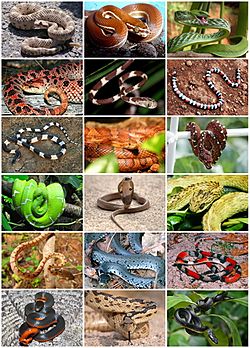

Snakes are amazing reptiles with long, narrow bodies and no legs. They are part of a group called Squamata. All snakes are carnivores, meaning they eat other animals. There are more than 3,400 different species of snakes, belonging to about 500 genera and 20 families.

The oldest snake fossils found are from the Jurassic period, which was over 143 million years ago. Snakes can be very tiny, like the 10.4 cm (4 inch) long thread snake. Or they can be huge, like the reticulated python which can grow up to 6.95 meters (22.8 feet) long! An extinct snake called Titanoboa was even bigger, reaching 12.8 meters (42 feet).

Snakes have special features that help them survive. Their bodies are covered in overlapping scales that protect them. These scales also help them move, climb trees, and even hide. Some scales have bright warning colours to tell predators to stay away.

Most snakes live in warm, tropical places. Only a few species live in colder areas. For example, the common viper (Vipera berus) is the only snake found beyond the Arctic Circle.

Contents

How Snakes Are Built

Snakes have unique bodies that help them hunt and live. They have no eyelids, so they can't blink. They also don't have external ears like humans do. While they can hiss, they don't make other loud sounds.

Flexible Jaws and Organs

A snake's skull has more joints than a lizard's skull. This allows snakes to open their mouths incredibly wide. They can swallow prey that is much larger than their own heads! The bones in their head and jaws can move apart to let big meals pass through. Their throat, stomach, and intestines can stretch a lot. This means a thin snake can eat and digest a much larger animal.

Because their bodies are so narrow, a snake's paired organs, like kidneys, are arranged one in front of the other instead of side by side. Most snakes also have only one working lung. Some snakes still have a small pelvic girdle with tiny vestigial claws. These are like tiny leftover parts from when snakes had legs.

Sensing the World

Snakes can see well enough to find their way around. They also use their tongues to "taste" the air. They flick their tongues in and out to pick up scents. This helps them find food and know what's around them. Snakes are also very sensitive to vibrations in the ground. Some snakes can even sense warm-blooded animals by feeling their body heat using special infrared pits.

Snake Evolution

Scientists believe that snakes evolved from lizards. The earliest snake fossils are from the Lower Cretaceous period. Many different types of snakes started to appear during the Paleocene period, about 66 to 56 million years ago.

A very old snake fossil, about 113 million years old, was found in Brazil. This ancient snake had small front and back legs. This discovery helps scientists understand how snakes lost their legs over millions of years.

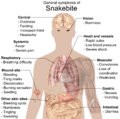

Snake Venom

Most snakes are not venomous. Snakes that do have venom use it mainly to catch and kill their prey. They don't usually use it for self-defense, unless they feel threatened. Some snake venoms are strong enough to cause serious injury or even death to humans. Nonvenomous snakes either swallow their prey alive or kill it by squeezing it very tightly.

There are two main families of snakes that are entirely venomous:

- Elapids: This group includes cobras (like king cobras), kraits, mambas, sea snakes, and coral snakes.

- Viperids: This family includes vipers, rattlesnakes, copperheads, and bushmasters.

A third family, the Colubrids, includes many "rear-fanged" snakes. Some colubrids, like boomslangs and vine snakes, are venomous, but not all of them are.

Shedding Skin

Snakes need to shed their skin regularly as they grow. This process is called moulting. To shed its skin, a snake rubs its head against something rough, like a piece of wood or a rock. This makes the old, stretched skin split open. The snake keeps rubbing until the skin peels off from its head. Then, it crawls out, leaving its old skin turned inside out.

How Snakes Eat

All snakes are carnivores, meaning they only eat other animals. Some snakes are venomous and inject poison into their prey using special teeth called fangs. Other snakes are constrictors. Constrictors are not venomous; they kill their prey by squeezing it until it can't breathe.

Snakes swallow their food whole because they cannot chew. Since snakes are cold-blooded (meaning their body temperature depends on their surroundings), they don't need to eat as often as mammals. Pet snakes might only eat once a month. Some snakes can even go for six months without a meal!

Their incredibly flexible lower jaw and many skull joints allow them to open their mouths very wide. This lets them swallow prey that is even wider than the snake itself.

How Snakes Move

Even without arms and legs, snakes are amazing movers! They have developed several unique ways to get around in different places.

Wavy Movement (Lateral Undulation)

This is the most common way snakes move, both on land and in water. The snake's body bends from side to side, creating waves that move backward.

On Land

When on land, these waves push against things like rocks, twigs, or bumps in the ground. Each push helps the snake move forward. The snake's body follows the path of the part in front of it. This allows snakes to move through thick plants or small spaces.

In Water

Snakes move through water by making wave-like motions with their bodies. The waves get bigger as they go down the snake's body. The snake pushes against the water to move forward. All snakes can move forward this way, but only sea snakes have been seen moving backward with this method.

Sidewinding

Snakes use sidewinding when there's nothing firm to push against, like on sand dunes or slippery mud. In this movement, parts of the snake's body stay still on the ground while other parts lift up. This creates a "rolling" motion. Sidewinding helps snakes move across slippery surfaces by only pushing off with the parts of their body that are not slipping. You can see this in their tracks, which show clear belly scale imprints without any smears.

Accordion Movement (Concertina)

When a space is too narrow for sidewinding, like in tunnels, snakes use concertina movement. The snake braces the back part of its body against the tunnel wall. Then, the front part stretches forward. The front part then grips the wall, and the back part is pulled forward. This movement is slow and uses a lot of energy.

Straight Movement (Rectilinear)

This is the slowest way a snake moves. The snake doesn't bend its body much from side to side. Instead, its belly scales lift and pull forward, then are placed down as the body is pulled over them. This creates ripples in the skin. Large pythons, boas, and vipers often use this method when hunting. Their movements are very subtle, making it harder for prey to notice them.

Other Cool Movements

Snakes also have special ways of moving in trees. On smooth branches, they might use a modified accordion movement. If there are things to push against, they will use their wavy movement.

Some snakes, like the gliding snakes (Chrysopelea) from Southeast Asia, can even glide through the air! They launch themselves from tree branches, spread their ribs, and make wavy motions as they glide between trees. They can glide for hundreds of feet and even steer themselves in mid-air.

Related pages

Images for kids

-

An adult Barbados threadsnake, Leptotyphlops carlae, on an American quarter dollar

-

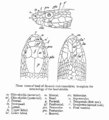

A line diagram from The Fauna of British India by G. A. Boulenger (1890), illustrating the terminology of shields on the head of a snake

-

A common watersnake shedding its skin

-

The skeletons of snakes are radically different from those of most other reptiles (as compared with the turtle here, for example), consisting almost entirely of an extended ribcage.

-

Innocuous milk snakes are often mistaken for coral snakes whose venom is deadly to humans.

-

The garter snake has been studied for sexual selection.

-

Dolichophis jugularis preying on a sheltopusik

-

A neonate sidewinder rattlesnake (Crotalus cerastes) sidewinding

-

The Indian cobra is the most common subject of snake charmings.

-

A "海豹蛇" ("sea-leopard snake", supposedly Enhydris bocourti) occupies a place of honor among the live delicacies on display outside a Guangzhou restaurant.

-

The reverse side of the throne of Pharaoh Tutankhamun with four golden uraeus cobra figures. Gold with lapis lazuli; Valley of the Kings, Thebes (1347–37 BCE).

-

Snakes composing a bronze kerykeion from the mythical Longanus river in Sicily

-

Imperial Japan depicted as an evil snake in a WWII propaganda poster

-

Medusa (1597) by the Italian artist Caravaggio

-

Rod of Asclepius, in which the snake, through ecdysis, symbolizes healing

-

Ballcourt marker from the Postclassic site of Mixco Viejo in Guatemala. This sculpture depicts Kukulkan, jaws agape, with the head of a human warrior emerging from his maw.

See also

In Spanish: Serpentes para niños

In Spanish: Serpentes para niños