Stephen Crane facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Stephen Crane

|

|

|---|---|

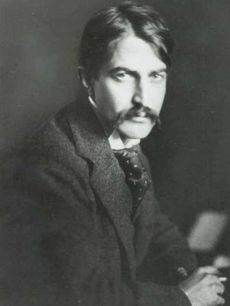

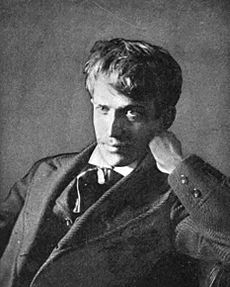

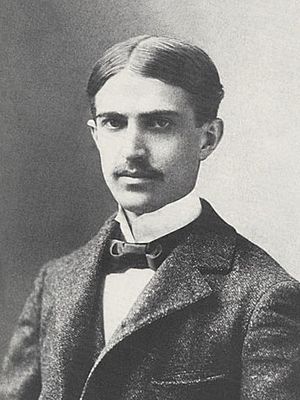

Formal portrait of Stephen Crane taken in Washington, D.C., about March 1896

|

|

| Born | November 1, 1871 Newark, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Died | June 5, 1900 (aged 28) Badenweiler, Grand Duchy of Baden, German Empire |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Signature | |

|

|

Stephen Crane (born November 1, 1871 – died June 5, 1900) was an American writer. He wrote poems, novels, and short stories. Even though he lived a short life, he wrote many important works. His writing style was known as Realism, Naturalism, and Impressionism. Today, many experts see him as one of the most creative writers of his time.

Stephen was the ninth child in his family. He started writing when he was only four years old. By the age of 16, he had already published several articles. He wasn't very interested in college studies. In 1891, he left Syracuse University to become a reporter and writer.

His first novel, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, came out in 1893. It was about life in a tough New York neighborhood called the Bowery. Many critics believe it was the first American book written in the Naturalism style. In 1895, he became famous around the world for his Civil War novel, The Red Badge of Courage. He wrote this book even though he had never been in a battle himself.

In 1896, Crane agreed to travel to Cuba as a war correspondent. This meant he would report on a war. While waiting in Jacksonville, Florida, he met Cora Taylor. They started a long-lasting relationship. On his way to Cuba, Crane's ship, the SS Commodore, sank off the coast of Florida. He and others were stuck in a small boat for 30 hours. Crane wrote about this scary experience in his famous story, "The Open Boat".

In his last years, he reported on wars in Greece. Cora, who was with him, became known as the first woman war correspondent. Later, they lived in England. He became friends with famous writers like Joseph Conrad and H. G. Wells. Stephen Crane had money problems and was often sick. He died from a lung illness called tuberculosis in Germany when he was only 28.

When he died, people thought Stephen Crane was a very important American writer. After about 20 years, people became interested in his life and work again. Crane's writing is known for being very strong and vivid. He used different ways of speaking (called dialects) and often used irony. His stories often explored themes like fear, big life changes, and feeling alone. Most people know him for The Red Badge of Courage, which is now an American classic. But he also wrote great poetry, news reports, and short stories. Some of his well-known short stories include "The Open Boat", "The Blue Hotel", and "The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky". His writing greatly influenced writers in the 1900s, especially Ernest Hemingway. He also inspired the Modernist and Imagist writing styles.

Contents

Stephen Crane's Life and Books

Early Life and School Days

Stephen Crane was born on November 1, 1871, in Newark, New Jersey. His father, Jonathan Townley Crane, was a minister. His mother, Mary Helen Peck Crane, was also from a religious family. Stephen was the last of their 14 children. His mother had lost four children before him, so she was very careful with him. His family called him "Stevie." He had eight older brothers and sisters.

The Crane family had been in America since the 1600s. Stephen was named after his great-great-grandfather, Stephen Crane, who was a patriot during the American Revolutionary War. Stephen Crane later said his father was a "great, fine, simple mind." His mother was a popular speaker for a group that worked against alcohol. Stephen was mostly raised by his older sister, Agnes. In 1876, his family moved to Port Jervis, New York.

As a child, Stephen was often sick with colds. When he was almost two, his father worried about him because he was so ill. But Stephen was a very smart child. He taught himself to read before he was four years old. When he was three, he asked his mother how to spell "O" while pretending to write. In 1879, he wrote his first poem about wanting a dog for Christmas. Stephen started school in 1880 and quickly finished two grades in six weeks.

His father died on February 16, 1880, when Stephen was eight. About 1,400 people came to his father's funeral. After his father's death, his mother moved. Stephen lived with his older brother Edmund and cousins for a while. Then he lived with his brother William, who was a lawyer, in Port Jervis.

His older sister Helen took him to Asbury Park, New Jersey. There, they lived with their brother Townley, who was a journalist. Townley worked for the New-York Tribune and the Associated Press. Another sister, Agnes, also joined them. She worked at a school and helped care for Stephen.

The Crane family faced more sadness. Townley and his wife lost their two young children. His wife, Fannie, died in 1883. Agnes Crane also became sick and died in 1884 at age 28.

Schooling and Early Writing

Crane wrote his first known story, "Uncle Jake and the Bell Handle," when he was 14. In 1885, he went to The Pennington School, a boarding school. His father had been the principal there. Soon after Stephen left for school, his mother became ill. Later that year, his brother Luther died after falling in front of a train. This was the fourth death in his close family in six years.

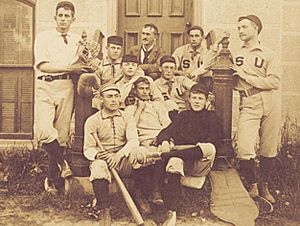

After two years, Crane left Pennington for Claverack College. This was a school with military training. He later said this was "the happiest period of my life." A classmate remembered him as a good reader but not always a good student in math or science. However, he was very good at history and literature. He was good at baseball, playing as a catcher. He also liked the military training and quickly moved up in the student ranks. Crane was seen as friendly but also quiet and rebellious. He sometimes skipped class to play baseball. Even though he wasn't strong in academics, his time at Claverack helped him when he wrote The Red Badge of Courage.

In 1888, Crane started helping his brother Townley at a news office in New Jersey. He worked there every summer until 1892. Crane's first published article with his name on it was about the explorer Henry M. Stanley. It appeared in his college newspaper in 1890. A few months later, his family convinced him not to join the military. He went to Lafayette College to study mining engineering. He played baseball and joined a fraternity. He didn't go to many classes and only got grades for four of his seven courses.

After one semester, Crane moved to Syracuse University. He joined the baseball team there too. He only took one class in his second semester.

Becoming a Full-Time Writer

Crane focused on his writing and started trying out different styles. He published a story called "Great Bugs of Onondaga" in two newspapers. He decided that college was "a waste of time" and chose to become a full-time writer and reporter. He left college for good in June 1891.

In the summer of 1891, Crane often camped with friends in Sullivan County, New York. He used this area as the setting for several short stories. These stories were published after his death in a collection called Stephen Crane: Sullivan County Tales and Sketches. He showed two of these stories to Tribune editor Willis Fletcher Johnson, who was a family friend. These were the first of 14 stories published in the Tribune between 1892. Crane also showed Johnson an early version of his first novel, Maggie: A Girl of the Streets.

Later that summer, Crane met and became friends with author Hamlin Garland. Garland became a mentor and supporter for the young writer. Their friendship later had problems because Garland didn't like that Crane was living with a woman who was married to someone else.

In the fall of 1891, Stephen moved into his brother Edmund's house in Lakeview, New Jersey. From there, he often went to New York City. He wrote reports, especially about the poor areas of the city. Crane was very interested in the Bowery, a neighborhood in Manhattan. After the Civil War, this area became full of bars and cheap hotels. Crane visited these places for his research. He felt that the people in the slums were "open and plain, with nothing hidden." He wanted to write an honest story about the Bowery, which became the setting for his first novel. On December 7, 1891, Crane's mother died. He was 20 years old, and his brother Edmund became his guardian.

In 1892, Crane started a relationship with Lily Brandon Munroe, a married woman who was separated from her husband. She said Crane "was not a handsome man" but admired his "remarkable almond-shaped gray eyes." He asked her to run away with him, but her family didn't approve because Crane didn't have much money. She refused.

Between July and September 1892, Crane published at least ten news reports about Asbury Park. His reports became more critical. One report he wrote caused a big problem. It described a parade in a way that made some marchers feel mocked. The newspaper's owner was running for vice-president, so the paper was very sensitive. Even though his brother defended him, the Tribune quickly apologized. The paper stopped publishing Crane's work after 1892.

Life in New York City

Crane found it hard to earn money as a freelance writer. He wrote articles for different New York newspapers. In October 1892, he moved into a boarding house in Manhattan. During this time, he worked on his novel Maggie: A Girl of the Streets. This book is about a girl who grows up in poverty and becomes a victim of her surroundings. In 1893, Crane tried to get Maggie published, but it was rejected.

Crane decided to publish it himself, using money he inherited from his mother. The novel was printed in early 1893 by a small shop. Crane used the fake name "Johnston Smith" for the first publication. He later said it was the "commonest name I could think of." Hamlin Garland praised the book, calling it "the most truthful... study of the slums." But Crane became sad and poor because he spent $869 to print 1,100 copies, and they didn't sell. He ended up giving away a hundred copies. He later remembered how he thought it would be a sensation, but it "fell flat."

In March 1893, Crane spent time in a friend's art studio. He became very interested in magazines about famous battles and leaders from the American Civil War. He found the stories too dry. He said, "I wonder that some of those fellows don't tell how they felt in those scraps." Crane kept reading these magazines, and soon he got the idea to write a war novel. He later said he had been thinking about war stories since he was a boy. This novel became The Red Badge of Courage.

From the start, Crane wanted to show what it felt like to be in a war. He wanted to write "a psychological portrayal of fear." He told the story from the point of view of a young soldier who first dreams of war glory. But then the soldier quickly becomes disappointed by the harsh reality of war. Crane worked mostly at night, from midnight until early morning. He wrote carefully in ink because he couldn't afford a typewriter. If he changed something, he would rewrite the whole page.

While working on his second novel, Crane kept writing many other things to avoid poverty. He wrote "An Experiment in Misery," which was based on his experiences in the Bowery. He also wrote five or six poems a day. In 1894, he showed some of his poems to Hamlin Garland, who was amazed. Even though Garland and William Dean Howells encouraged him, Crane's poems were written in a new style called free verse, which was unusual then. A publisher accepted his first book of poems, The Black Riders and Other Lines. It was published after The Red Badge of Courage.

In the spring of 1894, Crane offered his finished novel, The Red Badge of Courage, to McClure's Magazine. This magazine was known for Civil War stories. While McClure's thought about his novel, they offered him a job writing about Pennsylvania coal mines. Crane was reportedly upset by the changes made to his coal mine story.

Since McClure's couldn't pay him, Crane took his war novel to a newspaper group. They agreed to publish The Red Badge of Courage in parts. Between December 3 and 9, 1894, The Red Badge of Courage was printed in several newspapers across the United States. Even though it was shortened, it caused a stir. A newspaper in Philadelphia said that Crane was "a new name now and unknown, but everybody will be talking about him."

Famous Books and Travels

In January 1895, Crane went on a long trip for newspapers. He traveled to Saint Louis, Nebraska, New Orleans, Galveston, Texas, and then Mexico City. He found new things to write about in Mexico, especially the lives of poor people. He was impressed by how content the Mexican peasants were.

Five months later, he returned to New York. He joined a club for young writers and journalists. There, he ate one good meal a day. Friends worried about his "constant smoking, too much coffee, lack of food and poor teeth." Crane was living in poverty and waiting for his books to be published. He started working on two more novels: The Third Violet and George's Mother.

His poetry book, The Black Riders, was published in May 1895. But it received mostly bad reviews. One reviewer called him "the Aubrey Beardsley of poetry," and another said there was "not a line of poetry" in the book. Crane, however, was happy that the book was "making some stir."

In contrast, The Red Badge of Courage was highly praised when it was published in September 1895. For the next four months, it was one of the top-selling books. H. L. Mencken, who was about 15 at the time, said the book appeared "like a flash of lightning." It also became popular in Britain. Joseph Conrad said the novel "detonated... with the impact and force of a twelve-inch shell." Many critics praised it for its realistic look at war and its unique writing style. One newspaper said it would give readers "so vivid a picture of the emotions and the horrors of the battlefield that you will pray your eyes may never look upon the reality."

To build on the success of The Red Badge, a newspaper group offered Crane a contract. He would write a series about Civil War battlefields. Crane agreed because he wanted to visit the battlefields at the same time of year the battles happened. He visited battlefields in Northern Virginia, including Fredericksburg. He later wrote five more Civil War stories, such as "The Veteran" and "The Little Regiment."

The Shipwreck Adventure

In November 1896, Crane, then 25, was given $700 to work as a war correspondent in Cuba. He left New York for Jacksonville, Florida. In Jacksonville, he met 31-year-old Cora Taylor. She was a well-known local figure. They spent a lot of time together while Crane waited to go to Cuba. He finally left on New Year's Eve aboard the SS Commodore.

The ship sailed from Jacksonville with about 28 men and supplies for Cuban rebels. Near Jacksonville, the Commodore hit a sandbar in thick fog and damaged its bottom. The next day, it was damaged again. A leak started that evening, and the ship stopped about 16 miles from shore. Crane described the engine room as looking like "a scene... from the middle kitchen of hades." The ship's lifeboats were lowered early on January 2, 1897. The ship finally sank at 7 a.m. Crane was one of the last to leave the ship in a 10-foot dinghy.

In his short story "The Open Boat", Crane told about his experience. He and three other men, including the ship's Captain, were adrift off the coast of Florida for a day and a half. When they tried to land the dinghy at Daytona Beach, the small boat flipped over. The tired men had to swim to shore; one of them died. Crane had lost his money, so he asked Cora Taylor for help. She came to Daytona and returned to Jacksonville with him.

Newspapers across the country reported the disaster. Crane was seen as brave and heroic by the press. His reputation improved after this event. Meanwhile, his relationship with Cora Taylor grew stronger.

Later, from 2002 to 2004, archaeologists studied a shipwreck near Ponce Inlet. They found evidence that it was indeed the SS Commodore.

Reporting on Wars

Even though he was happy in Jacksonville and needed rest, Crane became restless. He left for New York City in January 1897. There, he applied for a passport to Cuba and other places. He spent three weeks in New York, finishing "The Open Boat." By this time, it was hard to travel to Cuba because of rising tensions with Spain. He sold "The Open Boat" for $300. Crane was determined to be a war correspondent. He signed with William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal to cover the upcoming Greco-Turkish conflict. He brought Cora Taylor with him, who had sold her hotel to follow him.

On March 20, they sailed to England, where Crane was welcomed. They arrived in Athens in early April. Crane wrote his first report of the war, "An Impression of the 'Concert'," between April 17 and 22. When he went to Epirus in the northwest, Cora stayed in Athens. She became the Greek war's first woman war correspondent. Crane had helped her get the job. They wrote to each other often and traveled separately and together.

Crane saw his first big battle when the Turks attacked Greek forces at Velestino. Crane wrote, "It is a great thing to survey the army of the enemy." During this battle, Crane found a "fat waddling puppy" and adopted it. He named it "Velestino, the Journal dog." Greece and Turkey signed a peace agreement on May 20, ending the 30-day war. Crane and Taylor left Greece for England, taking two Greek servants and Velestino the dog with them.

After staying in Limpsfield, Surrey, Crane and Taylor settled in Ravensbrook, a house in Oxted. They lived openly as Mr. and Mrs. Crane in England. But Crane kept their relationship a secret from his friends and family in the United States. Crane felt that people in America were trying to "kill, bury and forget me." Velestino the dog got sick and died on August 1. Crane loved dogs very much. He wrote an emotional letter to a friend, saying they had "fought death for him" for eleven days.

The area where they lived was home to many writers. Crane met the novelist Joseph Conrad in October 1897. Crane called their friendship "warm and endless."

Crane's literary reputation was suffering because of bad reviews for his recently published book, The Third Violet. Reviewers also criticized his war letters, saying they were too focused on himself. Even though The Red Badge of Courage had been printed many times, Crane was running out of money. To survive, he worked very hard, writing a lot for both English and American markets. He quickly wrote stories like The Monster, "The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky", and "The Blue Hotel". He hoped to sell "The Bride" for $175.

By the end of 1897, Crane's money problems got worse. A reporter and former girlfriend sued him for money. Crane felt "heavy with troubles" and "chased to the wall" by his expenses. He told his agent he was $2,000 in debt but would "beat it" by writing more.

Soon after a U.S. Navy ship exploded in Cuba in February 1898, Crane was offered money to write articles about a possible war between the United States and Spain. His health was getting worse. He may have had signs of tuberculosis. Since he wasn't earning much from his finished stories, Crane accepted the job. He left England for New York. Cora Taylor stayed behind to deal with their debts. Crane applied for a passport and left New York for Key West two days before Congress declared war. While waiting for the war to start, he interviewed people and wrote articles.

In early June, he saw American Marines take Guantánamo Bay in Cuba. He went ashore with the Marines, planning "to gather impressions and write them." Even though he wrote honestly about his fear in battle, others saw how calm he was. He later wrote about this experience in "Marines Signaling Under Fire at Guantanamo." Crane was praised for helping carry messages during a fight in Cuba.

He continued to report on battles and the worsening military conditions. He praised Theodore Roosevelt's Rough Riders. In early July, Crane was sent back to the United States for medical treatment for a high fever. He was diagnosed with yellow fever, then malaria. He rested in a hotel in Virginia. Even though Crane had sent over 20 reports, his newspaper fired him. In response, Crane signed with another newspaper, hoping to return to Cuba. He traveled to Puerto Rico and then to Havana. He sent out stories, but he soon needed money again. Cora Taylor, alone in England, was also broke. She worried a lot about him. They didn't talk directly until the end of the year. Crane left Havana and arrived in England on January 11, 1899.

Later Years and Legacy

The rent on their house in Ravensbrook hadn't been paid for a year. When Crane returned to England, he found someone to help with their debts. Then, Crane and Taylor moved to Brede Place. This old manor house in Sussex, built in the 1300s, had no electricity or indoor plumbing. Friends offered it to them for a low rent. Moving seemed to give Crane hope, but his money problems continued. He decided he couldn't afford to write for American newspapers anymore. He focused on publishing in English magazines.

Crane pushed himself to write very fast during his first months at Brede. He told his publisher he was "doing more work now than I have at any other period in my life." His health got worse. By late 1899, he was asking friends about health resorts. The Monster and Other Stories was being printed, and War Is Kind, his second poetry book, was published in the United States. None of his books after The Red Badge of Courage sold well. He bought a typewriter to write faster. Active Service, a novel based on his war reporting, was published in October. The New York Times reviewer wondered if the author "really sees anything remarkable in his newspapery hero."

In December, the couple held a big Christmas party at Brede. Friends like Conrad, Henry James, and H. G. Wells attended. It lasted several days. On December 29, Crane had a serious lung bleed. In January 1900, he felt well enough to work on a new novel, The O'Ruddy. He finished 25 of 33 chapters. He planned to travel as a correspondent to Gibraltar to write about a prison for soldiers. But in March and April, he had two more lung bleeds. Taylor handled most of Crane's letters while he was sick, asking friends for money. The couple planned to travel to Europe. But Conrad, after visiting Crane for the last time, said his friend's "wasted face was enough to tell me that it was the most forlorn of all hopes."

On May 28, the couple arrived at Badenweiler, Germany. It was a health spa. Even though he was weak, Crane kept telling parts of The O'Ruddy to be written down. He died on June 5, 1900, at the age of 28. In his will, he left everything to Taylor. She took his body to New Jersey for burial. Crane was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Hillside, New Jersey.

His Writing Style

Stephen Crane's stories are usually called Naturalism, American realism, or Impressionism. Some say his work combines Naturalistic ideas with Impressionistic methods. When asked if he would write about his own life, Crane said he was "as nearly honest as a weak mental machinery will allow."

Crane's writing style is often compared to Impressionist painting. This is because he used color and light and shadow (called chiaroscuro) in his descriptions. H. G. Wells noted "the great influence of the studio" on Crane's work. For example, in The Red Badge of Courage, he wrote: "Tents sprang up like strange plants. Camp fires, like red, peculiar blossoms, dotted the night." Crane strongly disliked overly emotional writing. He believed a story should be "logical in its action and faithful to character." He thought that being true to life was the most important thing.

One expert, John Berryman, said Crane had three main writing styles. The first was "flexible, swift, abrupt and nervous," seen in The Red Badge of Courage. The second was "supple majesty," found in "The Open Boat." The third was "much more closed," seen in later works like The Monster. Crane's writing is always immediate, focused, vivid, and intense. His novels and short stories have poetic qualities. They use short phrases, suggestions, and changes in perspective. Crane also often left things out. For example, he didn't always use his characters' names.

Early critics sometimes criticized Crane for using everyday speech in his dialogue. He copied the regional accents of his characters. This was clear in his first novel, where he ignored the romantic way other writers wrote about slums.

What He Wrote About

Crane's work often deals with themes from Naturalism and Realism. These include the difference between ideals and reality, big life changes, and fear. These themes are very clear in his first three novels: Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, The Red Badge of Courage, and George's Mother. The main characters in these books try to make their dreams come true but end up struggling with who they are.

Crane was fascinated by war and death. He also wrote about fire, injuries, fear, and courage. In The Red Badge of Courage, the main character wants to be a hero in battle but is also very afraid. This shows the contrast between courage and fear. He faces the threat of death, sadness, and losing himself.

Feeling very alone from society is also a common theme in Crane's work. In the most intense battle scenes of The Red Badge of Courage, the story focuses mainly on the soldier's inner thoughts. In "The Open Boat" and other stories, Crane uses light, movement, and color to show uncertainty. Like other Naturalistic writers, Crane looked closely at how humans are separated from society, God, and nature. "The Open Boat," for example, moves away from hopeful ideas about man's place in the world. Instead, it focuses on the characters' feeling of being alone.

During his life, people called Stephen Crane a realist, a naturalist, an impressionist, and a symbolist.

His Famous Novels

Crane became known as a novelist starting with Maggie: A Girl of the Streets in 1893. Many publishers first rejected Maggie. This was because it showed class struggles in a very real way, which was different from the emotional stories popular at the time. Instead of rich or middle-class people, the novel's characters are poor people from New York's Bowery. The story is simple, but its strong mood, fast pace, and realistic picture of Bowery life made it memorable. Maggie is not just about slum life; it also uses symbols that represent bigger ideas. The novel is full of bitter irony and anger. Critics later called it "the first dark flower of American Naturalism."

The Red Badge of Courage was written 30 years after the Civil War ended. Crane had no battle experience when he wrote it. It was new in its style and how it looked at people's minds. It's often called a war novel, but it focuses more on the main character's thoughts and feelings during war. Crane may have based the battle on the Battle of Chancellorsville. He might also have interviewed Civil War veterans in Port Jervis. The story is told from the point of view of Henry Fleming, a young soldier who runs away from combat.

The Red Badge of Courage is known for its vivid descriptions and rhythmic writing. These qualities help create suspense. Crane also used nicknames for his characters, like "the youth" or "the tattered soldier." This gives the story an allegorical feel, making the characters represent a certain human trait. Like Crane's first novel, The Red Badge of Courage has a strong ironic tone. The title itself is ironic. Henry wants "a red badge of courage," meaning a wound from battle. But the wound he gets is from another soldier's rifle, and it's a mark of shame, not courage.

The novel shows a strong connection between humans and nature. This was a common theme in Crane's writing. While other writers saw a friendly bond between the two, Crane wrote that human thought separated people from nature. In The Red Badge of Courage, this separation is shown with many references to animals. Men are described with animal-like traits: they "howl," "squawk," or "growl."

Since Crane became popular again in the 1920s, The Red Badge of Courage has been seen as a major American book. It has been included in many collections. Ernest Hemingway included it in his 1942 collection of war stories. Hemingway wrote that the novel "is one of the finest books of our literature."

Crane's later novels have not received as much praise. After The Red Badge of Courage was a success, Crane wrote another story set in the Bowery. George's Mother is more personal. It focuses on a conflict between a religious mother and her naive son. Critics had mixed opinions about it. The Third Violet, a romance, was written quickly. It is usually seen as Crane's attempt to appeal to more readers. Crane called it a "quiet little story." His second-to-last novel, Active Service, was about the Greco-Turkish War. It was not very successful. Critics generally agree that Crane's work suffered because he wrote so fast to pay his bills. His last novel, The O'Ruddy, was finished by another writer after Crane's death and published in 1903.

Short Stories and Poems

Crane wrote many different types of short stories. He used terms like "story," "tale," and "sketch" for them. This has made it hard for critics to classify his work. While "The Open Boat" and "The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky" are often called short stories, others are identified differently.

In an interview in 1896, Crane said that short stories were "the easiest things we write." During his short writing career, he wrote over a hundred short stories and sketches. His early stories were based on his camping trips as a teenager. These became known as The Sullivan County Tales and Sketches. He called these "sketches" because they were part fiction and part journalism.

The topics of his stories varied a lot. His early New York City and Bowery tales accurately described the effects of factories, immigration, and the growth of cities and their poor areas. His collection of six short stories, The Little Regiment, covered the American Civil War. This was a subject he became famous for with The Red Badge of Courage. But The Little Regiment was thought to lack energy and new ideas. Crane wrote: "I have invented the sum of my invention with regard to war."

The Open Boat and Other Stories (1898) contains 17 short stories. They cover three periods in Crane's life: his childhood in Asbury Park, his trip to the West and Mexico in 1895, and his Cuban adventure in 1897. This collection was well-received and included some of his most successful works. His 1899 collection The Monster and Other Stories was also praised.

Two collections published after his death were not as successful. In August 1900, The Whilomville Stories were published. This collection of 13 stories was written during the last year of his life. The stories are mostly about boyhood. They are based on events from Port Jervis, where Crane lived as a child. These stories focus on small-town America and are sometimes sentimental. Wounds in the Rain, published in September 1900, contains fictional tales based on Crane's reports during the Spanish–American War. These stories, which Crane wrote while very ill, are dramatic, ironic, and sometimes funny.

Even though Crane wrote a lot, only four stories—"The Open Boat," "The Blue Hotel," "The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky," and The Monster—have received a lot of attention from experts. H. G. Wells thought "The Open Boat" was "the crown of all his work."

Crane's poems, which he called "lines," are not usually studied as much as his stories. No collection of his poems was published until 1926. Crane once said his goal in poetry was "to give my ideas of life as a whole." The style of his two poetry books, The Black Riders and Other Lines and War is Kind, was unusual for his time. They were written in free verse without rhyme, meter, or even titles. They are usually short. Crane's work also used allegory and narrative situations.

Why Stephen Crane is Remembered

In just four years, Crane published five novels, two poetry books, three short story collections, two war story books, and many other short stories and reports. Today, he is mostly remembered for The Red Badge of Courage, which is an American classic. The novel has been made into movies several times, including John Huston's 1951 version. By the time he died, Crane was one of the most famous writers of his generation. His unique life, frequent news reports, friendships with other famous authors, and living abroad made him a bit of an international celebrity.

By the early 1920s, Crane and his work were almost forgotten. It wasn't until a biography was published in 1923 that his writing got attention from scholars. Crane's reputation was then helped by his writer friends like Joseph Conrad, H. G. Wells, and Ford Madox Ford. They all wrote about their memories of Crane. John Berryman's 1950 biography of Crane further showed him to be an important American author. Since 1951, many articles and books have been written about Crane.

Today, Crane is seen as one of the most creative writers of the 1890s. His friends, like Conrad and James, and later writers like Robert Frost and Ernest Hemingway, called Crane one of the best creative minds of his time. Wells described his work as "the first expression of the opening mind of a new period." Wells said that Crane was "the best writer of our generation." Conrad wrote that Crane was an "artist" with "incomparable insight into primitive emotions."

Crane's work has inspired many writers. Experts have found similarities between Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms and The Red Badge of Courage. Crane's stories are thought to have been an important inspiration for Hemingway and other Modernist writers. In 1936, Hemingway wrote that "The good writers are Henry James, Stephen Crane, and Mark Twain." Crane's poetry is thought to have led to the Imagist movement. His short stories have also influenced American literature. "The Open Boat," "The Blue Hotel," The Monster, and "The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky" are generally considered his best works.

Several places and groups work to keep Crane's memory alive. The health spa in Germany where he died became a tourist attraction. Columbia University has a collection of letters and other personal items from Crane and Cora Taylor. A pond near his brother Edmund's home in New York is named after him. The Stephen Crane House in Asbury Park, New Jersey, where he lived, is now a museum. Syracuse University has an annual Stephen Crane Lecture Series.

Columbia University bought many of Stephen Crane's materials after Cora Crane died. The Crane Collection there is one of the largest in the country. Columbia University had an exhibit about Stephen and Cora Crane from 1995 to 1996.

Selected works

- Maggie: A Girl of the Streets (1893)

- The Red Badge of Courage (1895)

- The Black Riders and Other Lines (1895)

- George's Mother (1896)

- The Open Boat and Other Tales of Adventure (1898)

- War Is Kind (1899)

- Active Service (1899)

- The Monster and Other Stories (1899)

- Wounds in the Rain (1900)

- Great Battles of the World (1901)

- The O'Ruddy (1903)

See also

In Spanish: Stephen Crane para niños

In Spanish: Stephen Crane para niños

| Charles R. Drew |

| Benjamin Banneker |

| Jane C. Wright |

| Roger Arliner Young |