Theodore Lukens facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

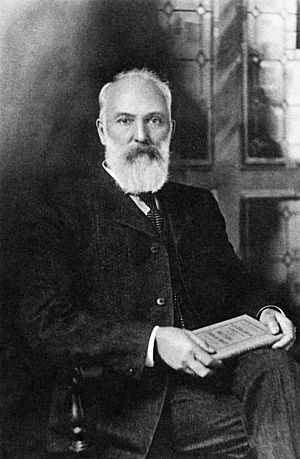

Theodore Parker Lukens

|

|

|---|---|

Lukens around 1890

|

|

| 4th Mayor of Pasadena | |

| In office May 1890 – May 1892 |

|

| Preceded by | Amos G. Throop |

| Succeeded by | Oscar F. Weed |

| 6th Mayor of Pasadena | |

| In office May 1894 – December 1895 |

|

| Preceded by | Oscar F. Weed |

| Succeeded by | John S. Cox |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 6, 1848 New Concord, Ohio |

| Died | July 1, 1918 (aged 69) Pasadena, California |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouses | Charlotte Dyer (1871 - 1905), H. Sibyl Swett (1906 - 1918) |

| Children | Helen Lukens Gaut (m. Feb.19, 1906 - James H. Gaut) |

| Parents | William E. Lukens, Margaret Cooper |

| Profession | Forester, conservationist |

Theodore Parker Lukens (October 6, 1848 – July 1, 1918) was an American conservationist, real estate investor, and leader in his community. He was also a forester. He believed that mountains damaged by fires could grow new trees. These new trees would help protect the areas where water collects, called watersheds.

Lukens collected different kinds of pine cones and seeds. He planted them on the mountain slopes above Pasadena, California. Because he never gave up, people called him the "Father of Forestry."

He created the Henninger Flats tree nursery. This nursery grew about 70,000 trees from seeds. Lukens worked for the United States Forest Service. In 1906, he was in charge of the San Gabriel Timberland Reserve and the San Bernardino Forest Reserve.

Lukens was mayor of Pasadena two times. He was very active in local government and community projects. He continued to work on community and conservation issues until he passed away in 1918.

Contents

Reforestation: Planting New Forests

Lukens loved growing plants even before he moved to Southern California. He used to own a plant nursery in Illinois. In 1882, his family moved to Pasadena. Lukens already knew about trees from the Midwest. Now, he wanted to learn about the trees in Southern California. These included live oak, pepper, camphor, umbrella, eucalyptus, and citrus trees.

From 1897 to 1899, Lukens explored the San Gabriel and San Bernardino Mountains. He learned that Southern California had big problems. Miners, loggers, and livestock owners had damaged the land. Wildfires caused the worst damage. Southern California has long, hot, dry summers. This made fires burn very hot, leaving bare hillsides. This led to erosion and flooding when it rained.

Lukens studied many tree types. He thought the knobcone pine was the best choice. This tree is good because it resists fire. Its cones stay closed until a wildfire. The heat from the fire makes them open and release seeds. Lukens learned how to open the cones by boiling them. He also learned how to water and care for the seedlings. The knobcone pine grows well on rocky hillsides. Botanist Willis Linn Jepson said it grows in the "most hopelessly inhospitable" places.

Lukens believed that planting trees was the answer. He gave talks, wrote articles, and took photos. His ideas gained support. In 1899, William Kerckhoff paid for $50 worth of seeds. These were for University of Southern California forestry students. In two weeks, they planted over 60,000 seeds. The next year, Lukens planted thousands of knobcone and ponderosa pine seeds. He planted them in the San Gabriel mountains above Altadena, California. He chose ridges and hilltops for planting. This way, seeds would spread down the slopes.

More people across California became interested in conservation. In 1899, 24 groups met in San Francisco. They formed The California Society for Conserving Water and Protecting Forests. Another group was The Forest and Water Society of Southern California. This group included the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce.

Henninger Flats Tree Nursery

In 1903, Lukens expanded his tree-planting work. He leased the Henninger property for the US Forest Service. He was an employee there. Chief Forester Gifford Pinchot approved the lease. Reforestation became an official policy. They built a lath house and a rabbit-proof fence. The first firebreak in the San Gabriel Timberland Reserve was around Henninger Flats. This was to protect the nursery. Lukens worked to make Henninger Flats a high-elevation tree nursery. It would grow seedlings for replanting forests and restoring watersheds.

Lukens and his helpers grew over 60,000 experimental tree seedlings. Most of the 1,000 trees planted in the San Gabriel and San Bernardino reserves came from this nursery. The nursery also provided 17,000 seedlings for Los Angeles' Griffith Park. This is the second-largest city park in California. The nursery received many orders for seeds and seedlings. These came from foresters all over the world. Galen Clark, a former guardian of Yosemite National Park, praised Lukens' work.

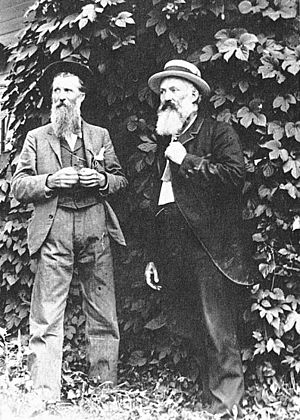

In 1907, John Muir visited the nursery. He was very impressed. A Los Angeles Times article in 1912 compared Lukens to the famous Johnny Appleseed. Local leaders also recognized his work. The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors visited the nursery. The Pasadena Star reported on June 21, 1915:

"It was truthfully and justly the proudest moment of Mr. Lukens' life. His work was ranked by the speakers as among the most important for the future of Southern California..."

Even though local people praised Lukens, the Forest Service had a different view. The Henninger Flats nursery closed in 1908. The Forest Service moved it to Lytle Creek. In 1912, a report said that tree planting efforts had failed. This was because of rabbits, rodents, and the hot sun. The Forest Service eventually stopped trying to turn chaparral into forests.

Lukens had chosen the property for good reasons. He had visited it in 1892. With the owner's permission, he planted some conifers there. These trees were doing well when Lukens returned ten years later.

History of the Henninger Property

The land belonged to Peter Stiel, who got it through the Homestead Act. In 1893, Stiel sold it to William Henninger. Henninger had lived there since 1884. Henninger was born in Virginia in 1817. He was one of the pioneers who came to California in the 1800s. He helped discover the first major gold strike in the San Gabriel Mountains. He settled in a small valley above Altadena.

From 1884 to 1891, Henninger lived on the 120-acre site. He called it Clara Basin, after a grandchild. He built a house and a water tank. He cleared the land and planted hay, melons, vegetables, and fruit trees. He carried his produce down a steep trail he built.

Henninger died in 1894. His daughters inherited the property. They sold it at auction in 1895 for $2,600. Later that year, it was sold again for $5,000. Then, in December 1895, it was sold to the Mt. Wilson Toll Road Company for $76,600. The price of this land went up a lot in one year!

The property was mostly empty until Lukens visited again in 1902. The Mt. Wilson Toll Road Company owned Henninger Flats until 1928. Then, Los Angeles County bought it. Today, the county fire department manages the site. It is now called the Henninger Flats Conservation Center. It has a museum, campground, and tree nursery.

Forester: Protecting Forests

Lukens worked for the US Forest Service from 1900 to 1906. John Muir first suggested him to Chief Forester Gifford Pinchot in 1899. Lukens was offered an honorary position for $300 a year. He traveled and wrote reports on forests. He also attended meetings. In 1906, he was promoted to Acting Supervisor. He was in charge of the San Bernardino Forest Reserve and the San Gabriel Timberland Reserve. The San Gabriel Reserve was the first federal reserve in California.

Lukens knew how dangerous wildfires were in the mountains. He pushed for more firefighters. The Forest Service agreed. A study by California and the US Forest Service found the forests in bad shape. Fires, overgrazing, and land clearing damaged watersheds every year. Logging had also harmed the forests. This led to the California legislature passing the Forest Protection Act. This law created a State Board of Forestry with a State Forester.

Lukens hired 55 men for firefighting and other jobs. But less than a year later, he was told to cut the force to 25. He thought this was wrong. He wrote letters to Pinchot and friends to try to change the order.

While Lukens was on vacation, Chief Pinchot moved him to a "special position." This new job was about forestry extension services. The agency also made mistakes with his pay. Lukens resigned on August 12, 1906. This also ended his work at Henninger Flats.

Conservationist: Saving Nature

Lukens visited Yosemite National Park many times. Each trip made him more interested in nature. He researched, wrote letters, and interviewed experts. He collected plant samples and took photos.

Lukens joined the Sierra Club in 1894 after visiting Yosemite and the Sierra Nevada Mountains. He taught himself photography. He made photo albums of trees and mountains for friends.

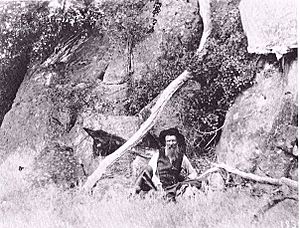

In 1895, he went to Yosemite's Hetch Hetchy Valley to meet the famous conservationist John Muir. Lukens found Muir, who was traveling alone.

Lukens convinced Muir to join his group. They went back to Hetch Hetchy Valley. Lukens took a photo called "John Muir Resting." The two men talked about protecting forests and restoring watersheds. They also discussed Southern California wildfires.

Lukens and Muir found out they shared a friend, Jeanne Smith Carr. Her husband had been Muir's professor. The Carrs had moved to Pasadena. Lukens and Jeanne Carr were on committees together and shared an interest in growing trees.

As they explored, Lukens studied pine trees, soil types, and how trees grow. He noted their height and age. He collected pine cones and learned from Muir's writings about conifers.

The sugar pine was Muir's favorite. He called it "surpassing all others, not merely in size but in lordly beauty and majesty." Sugar pines are the largest and tallest pine trees. They can be over 200 feet tall. Their cones are the longest, up to 24 inches.

During their trip, they camped at Tenaya Lake. They met Gertrude Towne and Nellie Anderson. Muir and Lukens led them up Mount Conness to the top. The next day, they climbed Mount Dana. Lukens and Muir remained friends until Muir's death in 1914.

Sierra Club: Working for Parks

John Muir, as president of the Sierra Club, asked Lukens to help with campaigns. These included buying private toll roads for public use in Yosemite. They also worked to protect Hetch Hetchy Valley.

Muir asked Lukens to write articles and speak about government-owned toll roads. He also wanted California to give Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees to the federal government. These areas were managed by the state at the time.

Lukens wrote to newspapers about the Sierra Club's goals. He wrote to the Pasadena Daily News: "The small portion of this great park now owned and controlled by the State of California should be receded to the national government, and have it all under one management. then there would be no need of petition for roads. The whole park would be cared for as the Yellowstone now is..."

Lukens spent most of 1896 working on conservation politics. He also spent three months climbing in Yosemite. He was with Walter Richardson, a young man from Pasadena. They wrote about their trip. They built a trail into Tehipite Valley, which Richardson named "Lukens Trail."

They had special permission to carry firearms for "personal protection." Hunting was not allowed in the park. While they stayed at a private cabin, five bears were killed. Lukens' journals do not show guilt. This might be because he was on private land. The US Army, which enforced park laws, saw this as a violation of the permit.

This incident led to letters between Lukens and Muir. Lukens did not apologize for the hunting. But Muir then pushed for creating wildlife refuges in national parks. He called it a "wild beast paradise." Both men continued their conservation work.

In 1897, Lukens began working to protect the San Gabriel Reserve's watershed. He wanted fire protection, tree planting, and to remove stockmen from the reserve. He believed sheep destroyed mountain meadows by eating all the plants. He also thought stockmen started wildfires to create more grazing land.

Lukens' first tree planting trip was in 1900. Fifteen years later, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors visited Mt. Wilson. They saw his earlier work. The Los Angeles Times reported on June 12, 1915: "As the father of reforestation of these mountains, it was a happy day for T.P. Lukens..."

Early Life and Pasadena

Lukens was born in Ohio on October 6, 1848. His family was German Quaker. When he was six, his family moved to Illinois and started a nursery business. At 20, he joined the US Cavalry. He left two years later. He married Charlotte Dyer. He started his own nursery, growing fruit and ornamental trees. He also worked as a tax collector from 1873 to 1876.

His only child, Helen, was born in 1872. When Helen was eight, he moved his family to California. They were facing some challenges with his money and health.

Settling in Pasadena

The Lukens family settled in Pasadena in December 1880. Theodore Lukens became active in his new community. By 1884, he was elected Justice of the Peace. He also joined the new Republican Committee.

Two years later, a land boom in Southern California made Lukens wealthy. He was the first real estate agent in Pasadena. He sold many properties in the Raymond Tract, an early land division.

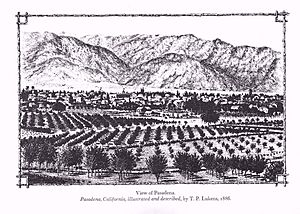

The year 1886 was busy. Pasadena became a town on June 14. The Pasadena National Bank opened. The 201-room Raymond Hotel opened in November. Lukens was able to semi-retire from real estate. He sold his properties and traveled. He wrote the first advertising booklet for Pasadena. It was called Pasadena, California, Illustrated and Described. He hoped hotel guests would settle in Pasadena.

In 1888, the Board of Trade was formed. Lukens was a founding member. This group was like an early chamber of commerce for Pasadena. It aimed to attract businesses and promote the city.

Pasadena's public library opened in 1890. Lukens helped raise money for it. He organized an Art Loan Exhibit in 1889. Each day had a different historical theme. On Russian Day, Lukens showed his Alaskan artifacts. On Forestry Day, speakers included Abbot Kinney, the State Forestry Commissioner.

In 1891, Lukens was a cashier for the Pasadena National Bank. By 1895, he was the bank president. He helped local banks during the Panic of 1893. This was a time when many banks struggled.

Serving as Mayor

Lukens served as mayor of Pasadena twice. His first term was from 1890 to 1892. His second term was from 1894 to 1895. He was replaced by John S. Cox. Lukens' second term ended on January 2, 1895. He was removed from office because he refused to approve a plan. This plan would have allowed the Southern Pacific Railroad to build a railway through Pasadena. There were already other train lines. The council voted against Lukens and for the railway. Lukens left office, sticking to his beliefs. Newspapers supported his decision. The Los Angeles Daily Hotel Gazette said, "To be disposed from a position for no other fault than standing for principles, is an honor rather than a disgrace."

During his first term as mayor, Lukens welcomed two important visitors. President Benjamin Harrison and First Lady Caroline visited Pasadena in March 1891.

Lukens was a member of many local groups. He was on the Pasadena World's Fair Committee. He provided orange trees and 60 palm trees for an exhibit. This was for the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1892. He received a medal of honor. Lukens also served as president of the Pasadena Mutual Building and Loan Association. He was a board member for two schools: the Los Angeles State Normal School (a college) and California Institute of Technology. He was also a member of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce.

Later Years and Legacy

Lukens became a grandfather in 1891 to Charlotte, and in 1893 to Ralph.

By 1903, Lukens and his first wife Charlotte were not well. Charlotte died in December 1905. Lukens then took a three-month break from the Forest Service. In July 1906, Lukens married Hannah Sybil Swett. She was a long-time family friend. He later adopted her religion.

In his final years, Lukens stayed active in local affairs and conservation. He supported creating a park above Devil's Gate Dam. This park eventually became Oak Grove Park. Two months before he died, Lukens wrote a report on conservation and forestry.

Theodore Lukens died on July 1, 1918. He is buried next to his first wife in Altadena, California. His second wife, H. Sybil Swett Lukens, died later that same year.

The Los Angeles Times published an obituary for Lukens on July 5, 1918. It said: "There is a new, growing forest of neglected pine trees on the slopes of the Sierras [San Gabriel Mountains] above Pasadena that stand as a living proof that Lukens could have reforested our mountains if we had only given him the help he asked."

A group called the Lukens Memorial Forestry Society was started. It promoted reforestation and lasted until the 1950s.

Helen Lukens: His Daughter

Helen, Lukens' daughter, became a published writer and photographer. She was well-known in the early 1900s. The photo of John Muir on the first page of his biography was taken by Helen Lukens.

She married Edward Everett Jones in 1890. He was the Bank of Pasadena cashier who replaced her father. They had two children, Charlotte and Ralph. Charlotte became a favorite of John Muir. Helen's marriage to Edward Jones ended. In 1906, she married James H. Gaut.

Helen Lukens Jones was the first woman to drive a car up the Mount Wilson Toll Road. This road was nine miles long and very steep.

Years after her father died, Helen sold his records, diaries, and papers to the Huntington Library. This collection has over 3,600 items. It is used in many studies today.

Tributes: Remembering Lukens

The "Father of Forestry" Theodore Lukens is remembered today. A mountain and a lake in Yosemite are named after him. His home is also listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Sister Elsie Peak was renamed to Mount Lukens in the 1920s. Mount Lukens is the highest point in Los Angeles city limits. It is 5,074 feet (1,546.5 m) high.

Robert Bradford Marshall, from the US Geological Survey, named a lake in Yosemite National Park for Lukens in 1894.

The Lukens family home at 267 N. El Molino Avenue in Pasadena was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984. The house was designed by Harry Ridgeway. He also designed the city jail and some early churches in Pasadena.

Images for kids

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |