Trinity (nuclear test) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Trinity |

|

|---|---|

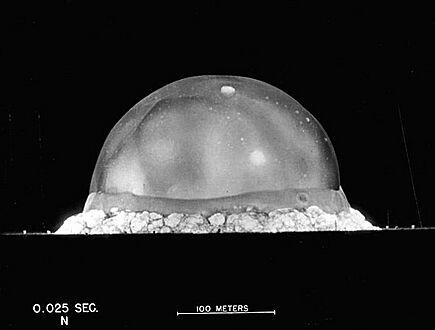

Detonation of the "gadget", with an estimated yield of 25 kilotons of TNT, and the ensuing mushroom cloud

|

|

| Information | |

| Country | United States |

| Test site | Trinity Site, New Mexico |

| Date | July 16, 1945 |

| Test type | Atmospheric |

| Device type | Plutonium implosion fission |

| Yield | 25 kt (100 TJ) |

| Navigation | |

| Next test | Operation Crossroads |

Trinity was the secret name for the very first time a nuclear weapon was exploded. This happened on July 16, 1945, at 5:29 a.m. in New Mexico, USA. It was a big part of the Manhattan Project, a secret effort by the United States Army.

The test involved a special type of bomb called an "implosion-design" plutonium bomb. Scientists nicknamed it the "gadget." This was the same kind of bomb, called Fat Man, that was later dropped on Nagasaki, Japan. Scientists needed to test this complex bomb design to make sure it would work. J. Robert Oppenheimer, who led the Los Alamos Laboratory, chose the name "Trinity." He was inspired by the poems of John Donne.

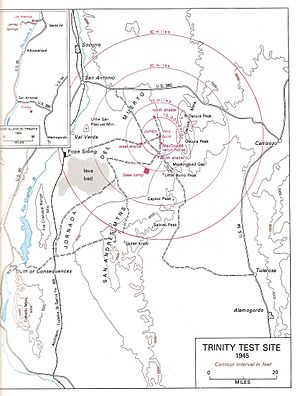

The test was planned and led by Kenneth Bainbridge. It took place in the Jornada del Muerto desert, about 35 miles southeast of Socorro, New Mexico. This area was part of a bombing range. The only buildings nearby were the McDonald Ranch House, used by scientists as a lab. There were worries the test might not work well, so a huge steel container called "Jumbo" was built to recover the plutonium. However, Jumbo was not used in the actual test.

A practice test was done on May 7, 1945. It used 108 tons of regular explosives mixed with radioactive materials. About 425 people were there for the Trinity test weekend. Many famous scientists and military leaders watched. The Trinity bomb released energy equal to about 25,000 tons of TNT. It created a large cloud of fallout, which is radioactive dust. Even though thousands of people lived closer than later safety rules would allow, no one was moved before or after the test.

The test site was made a National Historic Landmark in 1965. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1966.

Contents

What Was the Manhattan Project?

The idea for nuclear weapons came from scientific discoveries in the 1930s. One big discovery was nuclear fission, which is how atoms can be split. At the same time, fascist governments were rising in Europe. Scientists, especially those who had fled from Nazi Germany, worried that Germany might build nuclear weapons. When they figured out that nuclear weapons were possible, the British and U.S. governments decided to build them.

These efforts became the Manhattan Project in June 1942. Leslie R. Groves, Jr. became its director. The main place for developing the weapons was the Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico. Physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer was in charge there. Other universities also helped with the research.

Making the special materials needed for the bombs, like uranium-235 and plutonium-239, was a huge challenge. It cost a lot of money. Uranium was made at a place called Clinton Engineer Works in Tennessee. Only a tiny part of natural uranium is uranium-235. It was very hard and expensive to get enough of it.

Plutonium is a man-made element. It has complex properties and is not found naturally. By mid-1944, only tiny amounts of plutonium had been made. But bombs needed kilograms of it. Scientists found that plutonium made in reactors contained another type, plutonium-240. This type could cause the bomb to explode too early, leading to a "fizzle" (a much smaller explosion). This meant the first bomb design, called "Thin Man," would not work.

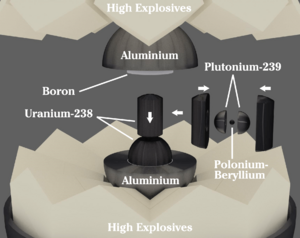

So, the scientists switched to a harder design: an implosion-type nuclear weapon. In this design, a core of plutonium is squeezed by powerful explosives. These explosives create shock waves that focus inward. This makes the plutonium much denser and causes a huge explosion. This complex process needed a lot of research and testing. The Los Alamos Laboratory changed its focus in August 1944 to work on this new bomb design.

Preparing for the Trinity Test

Why Test the Bomb?

In January 1944, scientists at Los Alamos started talking about testing the implosion bomb. Oppenheimer asked General Groves for permission. Groves was worried about losing the expensive plutonium if the test failed. He wanted to know if they could get it back.

One idea was a small test inside a sealed container. This would allow them to recover the plutonium. But Oppenheimer argued that the test needed to be a full-scale explosion. He wanted to see how much energy it would release. Groves finally agreed to a full-scale test, even though he was still concerned about the cost of lost plutonium.

How Trinity Got Its Name

No one is completely sure how the name "Trinity" was chosen. Many people think Oppenheimer named it after the poems of John Donne. These poems mention the Christian idea of the Trinity.

In 1962, Groves asked Oppenheimer about the name. Oppenheimer replied that he did suggest it. He said he was thinking of a poem by John Donne that talks about "three-person'd God."

Organizing the Test

In March 1944, Kenneth Bainbridge, a physics professor, was put in charge of planning the test. His group was called the E-9 (Explosives Development) Group. Stanley Kershaw was in charge of safety. Captain Samuel P. Davalos managed construction. First Lieutenant Harold C. Bush led the Base Camp. Many other scientists helped, forming seven smaller groups.

Choosing the Test Site

The test needed a very remote, quiet, and unpopulated area. Scientists also wanted a flat area with little wind. This would help reduce the effects of the blast and stop radioactive dust from spreading. They looked at eight possible locations in New Mexico, Colorado, and California.

The chosen site was in the northern part of the Alamogordo Bombing Range in Socorro County. This was near the towns of Carrizozo and San Antonio. The bombing range was renamed the White Sands Proving Ground just before the test. Even though the site was supposed to be isolated, almost half a million people lived within 150 miles of it.

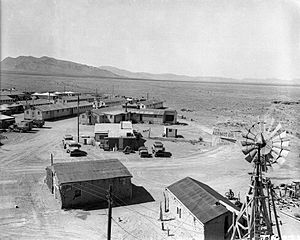

The only buildings nearby were the McDonald Ranch House. Scientists used it as a lab. Bainbridge and Davalos planned a base camp for 160 people. It would have living areas and technical equipment. By July 1945, 250 people worked at the Trinity site. On the test weekend, 425 people were there.

A group of 12 military police arrived in December 1944. They set up checkpoints and patrols. It was hard to keep spirits up because of long hours, harsh conditions, and dangerous animals. The base camp was even accidentally bombed twice in May by planes on practice night raids.

The "Jumbo" Container

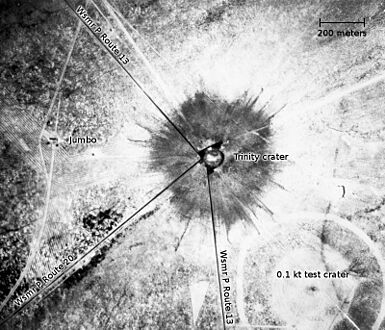

Scientists designed a huge steel container called "Jumbo." It was meant to hold the bomb if the test failed. This way, the valuable plutonium could be recovered. Jumbo was 10 feet wide and 25 feet long, with walls 14 inches thick. It weighed 214 tons. It was so heavy that a special train brought it from Ohio to New Mexico.

By the time Jumbo arrived, scientists were more confident the bomb would work. They also realized using Jumbo would make it harder to collect important data about the explosion. So, they decided not to use it for the test. Instead, Jumbo was placed on a steel tower 800 yards from the explosion.

Jumbo survived the explosion, but its tower did not. Jumbo was later destroyed in 1946. Its rusted remains are still at the Trinity site today.

The 100-Ton Practice Test

Bainbridge decided to do a practice test. This would help them check their plans and equipment. Oppenheimer at first wasn't sure, but later agreed it helped the main test succeed.

A 20-foot-high wooden platform was built. On it, 81 tons of regular explosives were stacked. This was equal to 108 tons of TNT. Radioactive materials were added to the explosives.

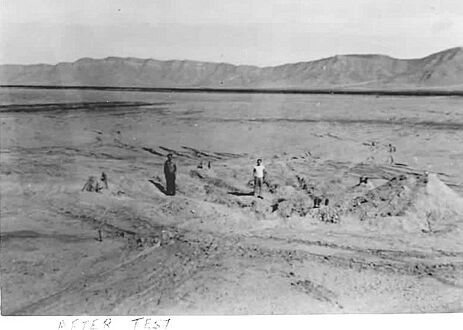

The practice test happened on May 7. The explosion's fireball was seen 60 miles away. A special lead-lined tank was used to collect soil samples from the crater. This test showed problems with equipment and communication. It led to better roads, more radios, and improved facilities for the main test.

Building the "Gadget" Bomb

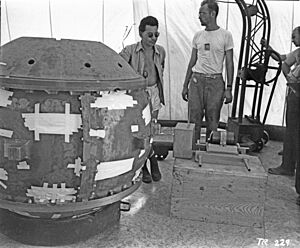

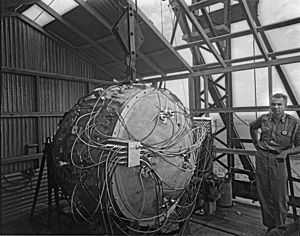

The bomb for the Trinity test was called the "gadget." It was very similar to the Fat Man bomb used in Nagasaki. The gadget was still being developed, so small changes were made to its design.

The bomb had a solid core of plutonium-gallium alloy. This core was plated with silver. The core produced heat, making it warm. The silver plating sometimes bubbled, so later bombs used nickel plating.

The bomb was put together at the McDonald Ranch House. The main bedroom was made into a very clean room. The "Urchin" initiator, which starts the nuclear reaction, was placed inside the plutonium core. Then the core was put into a uranium "tamper" plug.

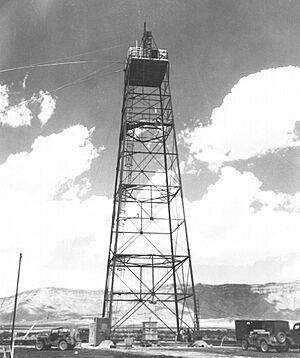

The bomb was designed to explode 100 feet in the air. This would help scientists understand its effects and create less radioactive fallout. The gadget was lifted to the top of a steel tower using an electric winch. Mattresses were placed below in case it fell.

The final parts of the bomb were put together on July 14. On July 15, a small team went to the tower to arm the bomb.

People at the Test

About 250 people from Los Alamos worked at the Trinity Site in the weeks before the test. Another 160 soldiers were ready to help move people if needed. They had enough vehicles and supplies for 450 people.

Shelters were set up 10,000 yards (about 5.7 miles) north, west, and south of the tower. Many other observers were about 20 miles away. Richard Feynman famously said he was the only one to watch the explosion without special goggles. He used a truck windshield to block harmful light.

Bainbridge limited the VIP list to ten people. These included Oppenheimer, Vannevar Bush, and James Chadwick. They watched from Compania Hill, about 20 miles away.

The observers even had a betting pool on how powerful the explosion would be. Edward Teller guessed 45 kilotons, while Oppenheimer guessed 0.3 kilotons. Isidor Isaac Rabi guessed 18 kilotons, which was the closest to the actual result. Enrico Fermi joked about whether the atmosphere would catch fire and destroy the world. Bainbridge was angry with Fermi for scaring the guards. Bainbridge's biggest fear was that nothing would happen at all.

The Explosion

The Detonation

Scientists wanted clear weather, low humidity, and light winds for the test. The best weather was expected between July 18 and 21. However, President Harry S. Truman wanted the test done before a big meeting called the Potsdam Conference, which started on July 16. So, the test was set for July 16.

The explosion was planned for 4:00 a.m. but was delayed due to rain and lightning. Rain could increase the danger from radiation. Lightning worried scientists about an accidental explosion. A good weather report came at 4:45 a.m., and the final countdown began at 5:10 a.m. By 5:30 a.m., the rain had stopped.

Two B-29 planes flew overhead to observe. They carried scientists who would measure things during the test. The cloudy sky made it hard for them to see the test site.

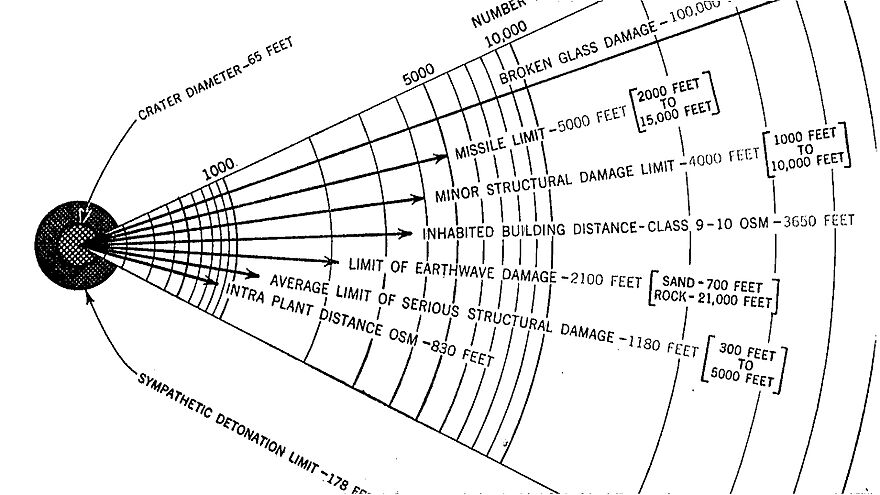

At 5:29:21 a.m., the bomb exploded. It released energy equal to about 24,800 tons of TNT. The desert sand, made of silica, melted into a slightly radioactive green glass called trinitite. The explosion left a crater about 4.7 feet deep and 88 yards wide. The trinitite spread out about 330 yards.

When the bomb went off, the mountains around the site lit up "brighter than daytime" for a few seconds. People at the base camp felt heat "as hot as an oven." The colors of the light changed from purple to green to white. It took 40 seconds for the sound of the shock wave to reach the observers. The sound was heard over 100 miles away. The mushroom cloud reached 7.5 miles high.

William L. Laurence, a reporter for The New York Times, was there to witness the test. He wrote press releases about it. Rabi noticed Oppenheimer's reaction: "I'll never forget his walk... his walk was like High Noon... this kind of strut. He had done it."

Oppenheimer later remembered a verse from a Hindu holy book, the Bhagavad Gita:

|

दिवि सूर्यसहस्रस्य भवेद्युगपदुत्थिता। |

If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, |

He also thought of another verse: "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds."

A pilot flying 30 miles east of Albuquerque saw the blast. He said, "My first impression was, like, the sun was coming up in the south. What a ball of fire!" He was told, "Don't fly south."

Measuring the Explosion

Scientists had predicted the bomb would have a yield of 5 to 10 kilotons of TNT. After the blast, two lead-lined tanks went into the crater. They collected soil samples. Analyzing these samples showed the total energy released was about 18.6 kilotons. This method became a very accurate way to measure nuclear explosions.

Many sensors were used to measure the blast wave. Most of them were destroyed by the explosion. But enough data was collected to measure the gamma rays released.

About 50 different cameras were set up. Some took fast motion pictures, 10,000 frames per second. Others recorded the light wavelengths or gamma rays. One camera took the only known color photo of the explosion.

The official estimate for the Trinity bomb's total energy was 21 kilotons of TNT. About 15 kilotons came from the plutonium core. The other 6 kilotons came from the uranium tamper. A newer study in 2021 put the yield at 24.8 kilotons.

The data from Trinity helped decide how high to detonate the bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This height was chosen to make the blast more powerful.

Public Reaction and News

Civilians noticed the bright flash and huge explosion. General Groves had a cover story ready. He told the Air Force to say it was an accidental explosion of a magazine (storage building) on the base.

A reporter named Laurence had prepared different news releases. One was for a successful test, which was used. Others were for worse outcomes, like damage to towns or deaths. Laurence knew if the worst happened, his own obituary might be published. Newspapers in New Mexico reported the blast. It was seen and felt over a wide area. But East Coast newspapers did not report it.

Information about the Trinity test became public after the bombing of Hiroshima. A report called the Smyth Report gave some details. It included famous pictures of the Trinity fireball.

Official Messages

A message about the successful test reached President Truman at the Potsdam Conference. It was taken to him and Secretary of State James F. Byrnes.

Three days later, a 13-page report from Groves arrived. It described the test vividly and estimated the yield at 15-20 kilotons. Truman was very happy about it. Winston Churchill, who was also there, noticed Truman's new confidence. He felt Truman had become "a changed man" after the news.

Radioactive Fallout

Special badges showed that observers at the shelters were not exposed to too much radiation. The shelter was moved before the radioactive cloud reached it. The explosion was more powerful than expected. Most of the radioactive cloud went high into the sky.

However, the crater itself was very radioactive because of the trinitite. The crews of the lead-lined tanks were exposed to a lot of radiation. One driver who made three trips recorded 13 to 15 roentgens of exposure.

The heaviest fallout outside the test area was 30 miles away. It was reported as a white mist that settled on livestock. Some animals got skin burns and lost hair. The Army bought 88 cattle from ranchers.

A study in 2020 showed that five counties in New Mexico had the most radioactive contamination. People living near the site did not know about the project. They were not included in a 1990 law that helped people affected by similar tests in Nevada. Efforts are still ongoing to include New Mexico residents in this support.

In August 1945, a company called Kodak noticed spots on their film. An employee figured out it was from a nuclear explosion in the U.S. He kept this secret until 1949. The contamination came from river water used by a paper mill. This water had been affected by fallout. This event led to rules for future tests. Officials gave photographic companies maps of possible contamination. This helped them protect their materials.

The Trinity Site Today

In September 1953, about 650 people visited the Trinity Site for the first time. Visitors can now see the ground zero area and the McDonald Ranch House. More than 70 years after the test, the radiation at the site is still about ten times higher than normal. However, a one-hour visit exposes you to about half the radiation an adult gets on an average day from natural sources.

On December 21, 1965, the Trinity Site was named a National Historic Landmark. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1966. The landmark includes the base camp, ground zero, and the McDonald ranch house. An old measurement bunker is still visible near ground zero.

A monument, a 12-foot-high stone obelisk, marks the exact spot of the explosion. It was built in 1965 using local rocks. On July 16, 1995, 5,000 visitors came for the 50th anniversary. The site is now open to the public on the first Saturdays of April and October.

Images for kids

Trinity in Movies and TV

The Trinity test has been shown in many movies and TV shows. In 1946, a documentary called Atomic Power was made. It showed people involved in the project acting out real events. In 1947, a movie called The Beginning or the End also showed the test.

In 1980, a TV series called Oppenheimer showed the Trinity test in its fifth episode. A documentary from 1981, The Day After Trinity, focused on the test. In 1989, the movie Fat Man and Little Boy also showed it. Other documentaries like Trinity and Beyond (1995) and The Bomb (2015) also featured the test.

The 2023 movie Oppenheimer, directed by Christopher Nolan, showed the Trinity test in a very important scene. Nolan said it was "the fulcrum that the whole story turns on." He used real effects instead of computer-generated images for the explosion. The movie's popularity brought new attention to older films about the Trinity test.

See also

In Spanish: Prueba Trinity para niños

In Spanish: Prueba Trinity para niños

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |