Victor Herbert facts for kids

Victor August Herbert (born February 1, 1859 – died May 26, 1924) was an American composer, cellist, and conductor. He was born in Guernsey, had English and Irish family, and trained in Germany. While Herbert was a great cello player and conductor, he is most famous for writing many popular operettas. These shows were first performed on Broadway from the 1890s until World War I.

Herbert was also a key figure among the Tin Pan Alley composers. Later, he helped start the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP). He wrote a lot of music, including two operas, a cantata, 43 operettas, and music for plays. He also created many pieces for orchestras, bands, and solo instruments like the cello and violin.

In the early 1880s, Herbert began playing the cello in Vienna and Stuttgart. During this time, he also started writing orchestral music. In 1886, Herbert and his wife, Therese Förster, who was an opera singer, moved to the U.S. Both were hired by the Metropolitan Opera. In America, Herbert kept performing, taught at the National Conservatory of Music, conducted, and composed.

Some of his most famous instrumental pieces include his Cello Concerto No. 2 in E minor, Op. 30 (1894), which is still played today. He also wrote the Auditorium Festival March (1901). He led the Pittsburgh Symphony from 1898 to 1904. After that, he started the Victor Herbert Orchestra, which he conducted for the rest of his life.

Herbert started writing operettas in 1894. Many of them became very popular, like The Serenade (1897) and The Fortune Teller (1898). Even more successful operettas came after 1900. These included Babes in Toyland (1903), Mlle. Modiste (1905), The Red Mill (1906), Naughty Marietta (1910), Sweethearts (1913), and Eileen (1917). After World War I, music tastes changed. Herbert then started writing musicals and helped other composers with their shows. While some of these were liked, he never reached the same level of success he had with his most popular operettas.

Contents

Victor Herbert's Life Story

Growing Up and Learning Music

Herbert was born on the island of Guernsey. His mother was Frances "Fanny" Muspratt. He was baptized in Germany in July 1859. From 1862 to 1866, Victor and his mother lived with his grandfather, Samuel Lover, in England. His grandfather was an Irish writer and composer. Their home was always full of musicians, writers, and artists.

In 1867, Herbert moved to Stuttgart, Germany, to live with his mother and her new husband, Carl Theodor Schmid. There, he got a good education, which included music lessons. Herbert first thought about becoming a doctor. However, medical school in Germany was expensive. So, he decided to focus on music instead.

He first learned to play the piano, flute, and piccolo. But he finally chose the cello. He studied the cello from age 15 to 18 with Bernhard Cossmann. Then he went to the Stuttgart Conservatory. He studied cello, music theory, and composition. He graduated in 1879.

Early Career and Moving to America

Even before finishing his studies, Herbert was playing cello professionally in Stuttgart. He first played flute and piccolo, but soon focused only on the cello. By age 19, Herbert was a solo cellist with major German orchestras. He played in the orchestra of a rich Russian baron for a few years. In 1880, he was a soloist for a year with Eduard Strauss's orchestra in Vienna.

In 1881, Herbert joined the court orchestra in Stuttgart. He stayed there for five years. During this time, he wrote his first instrumental pieces. He played the solo parts in his first two big works: the Suite for cello and orchestra, Op. 3 (1883), and the Cello Concerto No. 1, Op. 8. In 1883, Johannes Brahms chose Herbert to play in a chamber orchestra to celebrate the life of Franz Liszt.

In 1885, Herbert met Therese Förster, a soprano singer. She had just joined the court opera where Herbert played. They fell in love and married on August 14, 1886. On October 24, 1886, they moved to the United States. Both were hired by the Metropolitan Opera in New York City. Herbert became the main cellist for the opera orchestra. Förster was hired to sing main roles. On their trip to America, they became friends with Anton Seidl, who would also become a conductor at the Metropolitan Opera.

Starting Music Life in New York City

Seidl became a very important guide for Herbert. He especially helped Herbert develop his skills as a conductor. When they arrived in New York, Herbert and Förster became active in the German music community. They met other musicians and artists at places like Luchow's cafe. Herbert gave out business cards saying he was a "solo cellist from the Royal Orchestra of his Majesty, the King of Wurtemberg. Instructor in cello, vocal music and harmony." He hoped to earn extra money teaching.

In her first season at the Met (1886–87), Förster sang many roles in German. Critics and audiences loved her. She was even on the cover of Musical Courier, a big music magazine. The next season, she sang the role of Elsa again. Then she left the Met to sing with the German-language Thalia Theatre. She continued to get good reviews. Even though her singing career didn't grow much more, Herbert and Förster were happy in New York. They decided to stay in America and later became citizens.

Herbert quickly became well-known in New York City's music scene. He played his first American solo cello concert on January 8, 1887. He performed his own Suite for Cello and Orchestra, Op. 3. The New York Herald newspaper said his playing was "infinitely more easy and graceful than that of most cello players." This good review led to more solo concerts that year.

In the fall of 1887, Herbert started his own 40-piece orchestra, the Majestic Orchestra Internationale. He conducted it and played cello solos. The orchestra only lasted one season, but it played in many important concert halls in New York. That same year, he started the New York String Quartet. This group gave free concerts for several years and received great reviews.

In the summer of 1888, Herbert became Seidl's assistant conductor for the New York Philharmonic's summer concerts. This was a very important job. Herbert conducted the 80-piece orchestra in both light and serious music. He continued working with the New York Philharmonic for eleven seasons, as an assistant, guest conductor, and solo cellist. In the fall of 1888, Herbert also led a music tour through the Midwest. This tour brought art music to new audiences.

Conducting and Composing Successes

On December 1, 1888, Seidl included Herbert's Serenade for String Orchestra, Op. 12 in a concert. Herbert himself conducted it. In January 1889, Herbert and violinist Max Bendix were soloists in the first American performance of Brahms's difficult Double Concerto. Conductor Theodore Thomas then invited Herbert to conduct and perform in Chicago. In 1889, Herbert formed the Metropolitan Trio Club. The Musical Courier praised Herbert's music and his cello playing.

Seidl brought Herbert, Förster, and other famous musicians to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in May 1889. This was part of a big music festival to celebrate a new building. Herbert also played and conducted for the Worcester Music Festival many times in the 1890s. In the fall of 1889, Herbert also began teaching cello and music composition at the National Conservatory of Music. In 1890, he became the conductor of the Boston Festival Orchestra.

In 1891, Herbert presented a large cantata called The Captive. His Irish Rhapsody (1892) was popular for a short time. In 1894, he became the director of the 22nd Regimental Band of the New York National Guard. He toured widely with this band until 1900. He played his own band music and orchestral pieces that he arranged for the band. Herbert was always liked by orchestra players because he was modest and down-to-earth. He continued to write orchestral music, including his beautiful Cello Concerto No. 2 in E minor, Op. 30, which premiered in 1894.

In 1898, Herbert became the main conductor of the Pittsburgh Symphony. He held this job until 1904. Under his leadership, the orchestra became one of America's best. It was compared to famous groups like the New York Philharmonic. The orchestra toured many cities. They first performed Herbert's Auditorium Festival March in Chicago in 1901.

In 1904, Herbert had a disagreement with the Pittsburgh Symphony's management and resigned. He then started the Victor Herbert Orchestra. He conducted this orchestra for most of his remaining years. They played light orchestral music and more serious pieces. His orchestra made many recordings for Edison Records and the Victor Talking Machine Company. Herbert also played cello solos in some Victor recordings.

Fighting for Composers' Rights

In the early 1900s, Herbert fought for composers to earn money from their music. In 1909, he spoke to the United States Congress. His words helped create the Copyright Act of 1909. This law helped composers get paid royalties when their music was sold as recordings.

Herbert led a group of composers and publishers to create the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) on February 13, 1914. He became its vice-president and director until he died in 1924. ASCAP works to protect the rights of songwriters and music publishers. In 1917, Herbert won an important lawsuit in the United States Supreme Court. This ruling gave composers, through ASCAP, the right to charge fees when their music was played publicly. In 1927, a statue of Herbert was placed in New York City's Central Park to honor him.

Operettas, Operas, and Musicals

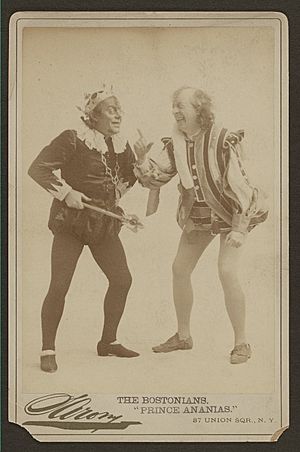

In 1894, Herbert wrote his first operetta, Prince Ananias. It was for a popular group called The Bostonians. The show was well-liked. Herbert soon wrote three more operettas for Broadway: The Wizard of the Nile (1895), The Serenade (1897), and The Fortune Teller (1898). These were popular, but Herbert didn't write any more stage shows for several years. He focused on his work with the Pittsburgh Symphony.

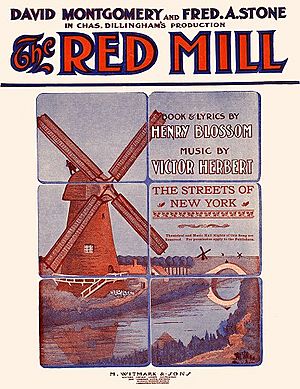

Just before leaving the orchestra, he returned to Broadway with his first big hit, Babes in Toyland (1903). Two more successes followed: Mlle. Modiste (1905) and The Red Mill (1906). These shows made Herbert one of America's most famous composers. He was chosen to join the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1908.

Even though Herbert is known for his operettas, he also wrote two grand operas. He looked for a good story for years. He finally found one by Joseph D. Redding called Natoma. It was a historical story set in California. He wrote the music from 1909 to 1910. It first played in Philadelphia on February 25, 1911. The opera's music was well-received. It was performed in New York City too.

Herbert's other opera, Madeleine, was a lighter, one-act show. It premiered on January 24, 1914, at the Metropolitan Opera. But it was not performed again after that season.

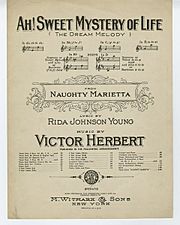

During this time, Herbert kept writing operettas. He created two of his most successful works: Naughty Marietta (1910) and Sweethearts (1913). He also became more involved with Irish-American groups. In 1916, he became the first president of the Friends of Irish Freedom. He was active in supporting Irish nationalism.

Another operetta, Eileen (1917), was Herbert's dream to write an Irish-themed show. It was also a tribute to his grandfather's novel. The story is set during the Irish Rebellion of 1798. It has rich music and opened around the first anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising in Ireland. This marked the end of Herbert's most productive period for operettas.

By World War I, music tastes in America were changing. Jazz, ragtime, and new dance styles like the foxtrot became popular. Herbert then started writing musical comedies. These shows had simpler songs and needed less classically trained singers. In his later years, Herbert often wrote ballet music for Broadway revues. He also contributed music to the Ziegfeld Follies every year from 1917 to 1924.

Death and Lasting Impact

Herbert was a healthy man his whole life. He died suddenly from a heart attack at age 65 on May 26, 1924. This happened shortly after his last show, The Dream Girl, began its tryout run. He was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in New York City.

Herbert and his music were celebrated in the 1939 film The Great Victor Herbert. He was also shown in the 1946 film Till the Clouds Roll By. Many of Herbert's own works were made into films. His music has been used in many movies and TV shows. In 1940, the U.S. Postal Service honored Herbert with a stamp. A school in Chicago is named after him. During World War II, a Liberty ship called SS Victor Herbert was built in his honor.

Victor Herbert's Music

Herbert wrote a lot of music. This included two operas, one cantata, 43 operettas, and music for 10 plays. He also wrote 31 pieces for orchestra, 9 for band, 9 for cello, and many songs. He even composed one of the first original orchestral scores for a full-length film, The Fall of a Nation (1916). This score was thought to be lost but was found later.

As a composer, Herbert is mostly remembered for his operettas. After he died, only a few of his instrumental pieces were still played often. However, some of his forgotten works have become popular again in recent years.

Operettas and Other Stage Music

Besides the ones already mentioned, other strong operettas by Herbert include Cyrano de Bergerac (1899), The Singing Girl (1899), The Enchantress (1911), The Madcap Duchess (1913), and The Only Girl (1914). Other popular shows were It Happened in Nordland (1904), Miss Dolly Dollars (1905), Dream City (1906), The Magic Knight (1906), Little Nemo (1908), The Lady of the Slipper (1912), The Princess Pat (1915), and My Golden Girl (1920). Herbert also wrote many songs for variety shows like the Ziegfeld Follies.

Herbert's early shows often toured widely. Broadway became very important for a show to be successful. Herbert designed his shows to appeal to New York audiences. While his music was always praised, critics often said his operettas had weak stories and typical lyrics. By the mid-1900s, Herbert's shows were rarely performed. However, in the 1970s and 1980s, his operettas started to be revived more often. Companies like the Light Opera of Manhattan and Ohio Light Opera began performing them again.

Herbert's Musical Style

American musical theater composers in the late 1800s often copied either Viennese operetta or the works of Gilbert and Sullivan. Many American theater groups performed Gilbert and Sullivan's operas. Herbert made his operettas suitable for these groups. His background made him very familiar with Viennese operetta. In fact, Herbert's most common song type was the waltz. Many of his waltzes became very popular, even though they were musically challenging.

Herbert is also known for his "variation" songs. These songs have different styles or variations of the same tune. For example, "Serenades of All Nations" from The Fortune Teller shows serenades from different countries. "The Song of the Poet" from Babes in Toyland changes the lullaby "Rock-a-bye Baby" into a march, then a Neapolitan style, and finally a cakewalk. The best of Herbert's operetta music is difficult and needs trained singers. He often wrote his operettas with a specific singer in mind. He worked with three great singers: Alice Nielsen, Fritzi Scheff, and Emma Trentini.

Although Herbert had not heard Gilbert and Sullivan before coming to the U.S. in 1886, their popularity influenced him. He adopted some of their musical and dramatic ideas. For example, the song "Cleopatra's Wedding Day" from The Wizard of the Nile shows this influence. His early success, The Serenade, borrowed many ideas from Gilbert and Sullivan's operas.

Herbert usually used a slightly larger orchestra than Sullivan. He often added more types of percussion and sometimes a harp. He generally wrote his own orchestrations, which other composers admired. However, in later revivals of his works, new orchestrations often replaced strings with saxophones and brass. For many years, the only recording of a Herbert show with his original orchestrations was Naughty Marietta. More recently, recordings of his operettas with original orchestrations have appeared.

Like Sullivan, Herbert often used music from different places in his operettas. He used Spanish music in The Serenade, Italian music in Naughty Marietta, and Austrian music in The Singing Girl. He also used Eastern music in shows set in places like Egypt and India. The Fortune Teller includes an energetic Hungarian csárdás. He also often put Irish-style songs into his operettas.

By World War I, musical tastes were changing in America. Herbert had to write in a simpler style. Many of his later works, like The Velvet Lady and Angel Face (both 1919), copied popular new song types like the foxtrot and tango. Even in some of his earlier works, like The Red Mill (1906), Herbert was already using elements that would become part of American musical comedy. His work with Irving Berlin on The Century Girl (1916) showed this simpler style. While these later shows had some memorable songs, they were not as popular as his earlier operettas. His most successful work in his later career was Orange Blossoms (1921). It included the popular waltz song, "A Kiss in the Dark."

Operas

Even though he was successful with light music, Herbert wanted to write serious operas. When Oscar Hammerstein I asked him to write a grand opera, Herbert was excited. Hammerstein offered a $1,000 prize for the best story idea. Joseph Redding's story for Natoma was a love story set in 1820s California. It was about an American naval officer and a Native American princess. Famous singers like John McCormack and Mary Garden were in the cast. The 1911 premiere in Philadelphia was only a moderate success. Critics liked the music but complained about the story and foreign singers playing American roles.

Madeleine, his only other opera, was based on a French play. It tells the story of an opera singer whose friends cannot join her for dinner on New Year's Day. This one-act work premiered in 1914. It was performed with Enrico Caruso in another opera. Frances Alda sang the main role in Madeleine. It did not make a strong impression and was only performed six times.

Instrumental Music

After Herbert's death, not much of his instrumental music was performed. But in the last few decades, it has started to be played and recorded again. His Cello Concerto No. 2 in E minor, Op. 30, is an exception. It was first performed in 1894 and was very popular. Antonín Dvořák, who worked with Herbert, was inspired to write his own Cello Concerto after hearing Herbert's. Famous cellists like Yo-Yo Ma and Julian Lloyd Webber have recorded Herbert's concerto.

More recently, two of Herbert's earlier cello and orchestra pieces have become popular again. The Suite for Cello and Orchestra, Op. 3 (1884), has been performed by several groups. It shows hints of the light music Herbert would write later. Another revived work is his Cello Concerto No. 1. This piece was first performed by Herbert himself in Stuttgart. For many years, it was not published or performed. It was first recorded in 1986 and has since been published. People admire it for balancing difficult parts with beautiful melodies.

Of his large orchestral works, Herbert's tone poem Hero and Leander (1901) is his most important. He wrote it for the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra while he was their conductor. Another important work he wrote for the orchestra is Columbus, Op. 35. This is a four-movement suite. The first and last movements were written in 1893 for a show in Chicago. However, Herbert never finished that project. The middle two movements were not written until 1902. The orchestra first performed the complete work in 1903. It was the last big symphonic work Herbert composed.

Herbert also wrote many smaller pieces. He often wrote music for himself to play on the cello. He also produced individual songs for the Victor Herbert Orchestra. He published some of his dance music under the name Noble MacClure. In the last ten years of his life, he wrote several overtures for movies. The Fall of a Nation was his only complete film score. On February 12, 1924, Herbert was one of the composers featured at New York's Aeolian Hall. This evening included the first performance of George Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue. Herbert's piece for the evening, A Suite of Serenades, was the last work he attended the premiere of.

Recordings of Herbert's Music

Here are some well-known recordings of Victor Herbert's music:

- The Music of Victor Herbert, conducted by Nathaniel Shilkret, Victor, 1927.

- The Music of Victor Herbert, conducted by Shilkret with soloists, chorus, and orchestra, RCA Victor, 1939.

- The Music of Victor Herbert, recorded by Beverly Sills, soprano, and Andre Kostelanetz, conducting, on Angel records (1976). This recording won a Grammy Award.

- Cello Concerto No. 2 in E minor op. 30, recorded by Julian Lloyd Webber, with the London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Sir Charles Mackerras on EMI Classics.

- Cello Concertos recorded by Lynn Harrell, with The Academy of St. Martin in the Fields, conducted by Sir Neville Marriner on Decca.

- Victor Herbert Eileen: Romantic Comic Opera in Three Acts (1998) Ohio Light Opera.

- Victor Herbert: Beloved Songs and Classic Miniatures (1999) recorded by Virginia Croskery, soprano, and Keith Brion conducting the Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra, on the Naxos CD.

- The Red Mill: Romantic Opera in Two Acts by Victor Herbert (2001) Ohio Light Opera.

- Stereo recordings of four Herbert operettas were made by Reader's Digest for their 1963 album Treasury of Great Operettas. These included Babes in Toyland, Mlle. Modiste, The Red Mill, and Naughty Marietta.

- Hero and Leander; Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Lorin Maazel. (1994) Sony.

- Columbus Suite / Irish Rhapsody, Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Keith Brion (2000) Naxos.

- Victor Herbert: The Collection, Victor Herbert And His Orchestra (2007) Syracuse University Recordings. These are restored recordings from Herbert's early cylinders.

See also

In Spanish: Victor Herbert para niños

In Spanish: Victor Herbert para niños

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |