Western esotericism facts for kids

Western esotericism is a term scholars use to describe a group of ideas and movements that grew in Western society. These ideas are different from mainstream Judeo-Christian religions and the Enlightenment's focus on reason. Esotericism has influenced many parts of Western thought, mysticism, religion, unproven sciences, art, literature, and music. It still shapes ideas and popular culture today.

The idea of putting these different Western traditions together under "esotericism" started in Europe in the late 1600s. Experts have different ways of defining it. Some see it as a secret, hidden tradition that has always existed. Others see it as a way of looking at the world as "magical" when many people started to see it as less so. A third view sees it as all the "rejected knowledge" in Western culture. This knowledge is not accepted by mainstream science or traditional religions.

The earliest ideas that became known as Western esotericism appeared in the Eastern Mediterranean during Late Antiquity (a long time ago!). Here, ideas like Hermeticism, Gnosticism, Neopythagoreanism, and Neoplatonism developed. These were different from what became mainstream Christianity. During the Renaissance in Europe, people became very interested in these old ideas. Scholars mixed "pagan" (non-Christian) philosophies with the Kabbalah (a Jewish mystical tradition) and Christian ideas. This led to new movements like Christian Kabbalah and Christian theosophy.

In the 1600s, secret groups like Rosicrucianism and Freemasonry formed. They claimed to have special, hidden knowledge. The Age of Enlightenment in the 1700s brought even more new esoteric ideas. The 1800s saw the rise of new esoteric trends called occultism. Important groups from this time include the Theosophical Society and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Modern Paganism, including religions like Wicca, also grew from occultism. Esoteric ideas were popular in the counterculture of the 1960s and led to the New Age movement in the 1970s.

The idea of grouping these movements under "Western esotericism" began in the late 1700s. However, for a long time, scholars mostly ignored them. The academic study of Western esotericism only started in the late 1900s. Scholars like Frances Yates and Antoine Faivre were pioneers in this field. Esoteric ideas have also influenced popular culture, appearing in art, books, movies, and music.

Contents

What Does "Esoteric" Mean?

The word "esoteric" comes from the Ancient Greek word esôterikós. This word means "belonging to an inner circle." It was first used around the 2nd century. One of the first times it appeared was in a funny story by Lucian of Samosata.

The word "esotericism" (in French, "ésotérisme") first showed up in 1828. It was in a book by a historian named Jacques Matter. This happened after the Age of Enlightenment, when people started to question traditional religion. Groups like the Rosicrucians began to separate themselves from mainstream Christianity.

In the 1800s and 1900s, scholars saw "esotericism" as something different from Christianity. It was seen as a subculture that often disagreed with mainstream Christian ideas. The French occultist Eliphas Lévi made the term popular in the 1850s. Later, the Theosophist Alfred Percy Sinnett brought it into the English language in his book Esoteric Buddhism (1883).

Understanding Western Esotericism

The idea of "Western esotericism" is a modern concept created by scholars. It's not a group that always called itself "esoteric." In the late 1600s, some European Christian thinkers started to group certain Western philosophies together. They called this new category "Western esotericism."

One of the first to do this was Ehregott Daniel Colberg. He was a German theologian who wrote a book called Platonisch-Hermetisches Christianity (1690–91). He criticized many Western ideas that came after the Renaissance. These included Paracelsianism and Christian theosophy. He called them "Platonic–Hermetic Christianity" and said they were against "true" Christianity. Even though he was against these ideas, Colberg was the first to connect them. He also saw that these ideas were linked to older philosophies from late antiquity.

In the 1700s, during the Age of Enlightenment, these esoteric traditions were often called "superstition", "magic", or "the occult". These words were often used to mean the same thing. Modern universities usually ignored these "occult" topics. This meant that people outside of universities mostly studied them. According to historian Wouter J. Hanegraaff, rejecting "occult" topics was important for scholars who wanted to be part of the university world.

Scholars created this category in the late 1700s. They noticed that many different thinkers and movements shared similar ideas. Hanegraaff said the term was a "useful label" for a "large and complicated group of historical phenomena." These phenomena seemed to have a "family resemblance."

Many experts say that esotericism is mostly a Western idea. Scholar Antoine Faivre said that "esotericism is a Western notion." There isn't a similar category for "Eastern" esotericism. The term "Western" helps to show that it's different from a general, worldwide esotericism. Hanegraaff described these as "recognizable ways of looking at the world and gaining knowledge." They have played an important, though often debated, role in Western culture.

Historian Henrik Bogdan said that Western esotericism is like a "third pillar of Western culture." The other two are "religious faith and reason." Esotericism was seen as wrong by faith and irrational by reason. However, scholars know that non-Western traditions have influenced Western esotericism a lot. For example, the Theosophical Society used Hindu and Buddhist ideas like reincarnation. Because of these influences, some scholars like Kennet Granholm think we should just say "esotericism" instead of "Western esotericism."

What Makes Something Esoteric?

Historian Antoine Faivre noted that esotericism is "never a precise term." He and Karen-Claire Voss said it includes "a vast spectrum of authors, trends, works of philosophy, religion, art, literature, and music."

Scholars generally agree on which ideas fit into esotericism. These range from ancient Gnosticism and Hermeticism to Rosicrucianism and the Kabbalah, and even newer movements like the New Age movement. But the word "esotericism" itself is still debated. Scholars who study it disagree on how to define it best.

Esotericism as a Hidden Tradition

Some scholars see "Western esotericism" as "inner traditions." These traditions deal with a "universal spiritual dimension of reality." This is different from the outward rules and beliefs of established religions. This view sees Western esotericism as one part of a worldwide esotericism. It is believed to be at the heart of all religions and cultures, showing a hidden spiritual reality. This meaning is close to the original idea of the word in ancient times. Back then, it meant secret spiritual teachings meant only for a special group, hidden from most people.

This definition became popular in the 1800s. Esoteric writers like A.E. Waite used it. They wanted to combine their own mystical beliefs with the history of esotericism. This idea then became popular within several esoteric movements.

This definition has some problems. The biggest one is that it assumes there is a "universal, hidden, esoteric dimension of reality" that truly exists. Science and research haven't proven this. Hanegraaff says we "simply do not know - and cannot know" if it exists. He points out that even if it did, we could only access it through "esoteric" spiritual practices. Science cannot measure it. Also, many groups known as esoteric never hid their teachings. In the 1900s, they became part of popular culture. This makes it hard to define esotericism by its secret nature.

Esotericism as a Magical View of the World

Another way to understand Western esotericism is as a worldview that believes in "enchantment" or magic. This is different from modern science, which tries to explain the world without magic. This view sees esotericism as believing that all parts of the universe are connected. They don't need a direct cause-and-effect chain. It's a different way of thinking compared to the non-magical views that have been common since the scientific revolution.

Frances Yates was an early supporter of this idea. She talked about a Hermetic Tradition as a magical alternative to religion and science. But the main person to develop this view was Antoine Faivre. In 1992, he listed six main features of esotericism:

- Correspondences: This is the idea that everything in the universe is connected, both really and symbolically. For example, the idea of "as above, so below" means that what happens in the heavens also happens on Earth. Astrology, which says planets affect humans, is another example.

- Living Nature: Esoteric thinkers see nature as alive and full of its own energy. They believe it is "complex, many-sided, and organized in levels."

- Imagination and Mediations: Esotericists value the human imagination greatly. They also use tools like rituals, symbols, and spiritual guides to connect with other levels of reality.

- Experience of Transmutation: This means that esoteric practices aim to change a person from the inside. For example, achieving gnosis (special knowledge) can lead to a spiritual change.

- Practice of Concordance: Many esotericists believe that all world religions and spiritual practices come from one basic, unifying truth. Finding this truth can bring different belief systems together.

- Transmission: This is about how esoteric teachings and secrets are passed down from a teacher to a student, often through a special process called initiation.

Faivre's ideas became very popular among scholars. However, some scholars have criticized his theory. They say it focuses too much on specific types of esotericism, like Christian esotericism from the early modern period.

Western Esotericism as "Rejected Knowledge"

Wouter Hanegraaff offered another definition. He said "Western esotericism" is like "the academy's dustbin of rejected knowledge." This means it includes all the ideas and worldviews that mainstream thinkers have rejected. They don't fit with common ideas about religion, reason, or science. This view looks at how ideas change over time.

Some scholars, like Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke, didn't like this idea. They felt it made Western esotericism seem unimportant.

A Look at History

Ancient Beginnings

Western esotericism began in the Eastern Mediterranean during Late Antiquity. This area was part of the Roman Empire. It was a mix of ideas from Greece, Egypt, the Middle East, Babylon, and Persia. This time saw many changes, with people moving to cities and different cultures mixing.

One important part was Hermeticism. This Egyptian-Greek idea is named after the wise man, Hermes Trismegistus. In the 2nd and 3rd centuries, texts like the Corpus Hermeticum appeared. These texts talk about the true nature of God. They say humans must go beyond normal thinking and desires to find salvation. They believed people could be reborn into a spiritual body of light and become one with the divine.

Another ancient esoteric idea was Gnosticism. Different Gnostic groups believed that divine light was trapped in the material world. This was done by a bad being called the Demiurge and its helpers, the Archons. Gnostics believed that people had divine light inside them. They should seek gnosis (special knowledge) to escape the material world and return to the divine source.

A third ancient form of esotericism was Neoplatonism. This idea was influenced by the philosopher Plato. Thinkers like Plotinus believed the human soul fell from its divine home into the material world. But it could move through different levels of existence to return to its divine origins. Later Neoplatonists performed theurgy. This was a ritual practice, possibly involving making gods appear. These gods could then help the person's mind reach divine reality.

Medieval Times

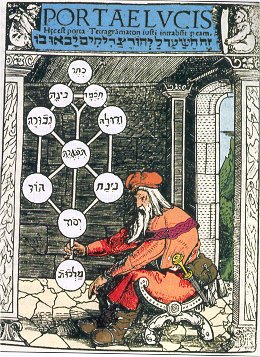

After the fall of Rome, ideas like alchemy and philosophy were kept alive in the Arab and Near Eastern world. They were brought back to Western Europe by Jews and through contact between Christians and Muslims in Sicily and southern Italy. In the 1100s, the Kabbalah developed in southern Italy and medieval Spain.

The medieval period also saw the creation of grimoires. These were books with detailed instructions for theurgy (calling on gods) and thaumaturgy (performing wonders). Many grimoires seemed to be influenced by Kabbalah. Alchemists from this time also wrote or used grimoires. Some medieval groups, like the Waldensians, were thought to use esoteric ideas.

Renaissance and Early Modern Period

During the Renaissance, European thinkers started to combine "pagan" (non-Christian) philosophies with Christian ideas and the Jewish kabbalah. These pagan ideas were becoming available through Arabic translations. One of the first was the Byzantine philosopher Plethon. He believed the Chaldean Oracles showed a superior ancient religion.

Plethon's ideas interested Cosimo de Medici, the ruler of Florence. He hired Marsilio Ficino to translate Plato's works into Latin. Ficino also translated parts of the Corpus Hermeticum. He argued that these philosophies fit well with Christianity. This led to a wider movement called Renaissance Platonism.

Another key figure was Giovanni Pico della Mirandola. In 1486, he invited scholars to debate 900 ideas he had written. He believed all these philosophies showed a great universal wisdom. However, Pope Innocent VIII condemned his ideas. The Pope criticized him for mixing pagan and Jewish ideas with Christianity.

Pico della Mirandola's interest in Jewish Kabbalah led to Christian Kabbalah. Johannes Reuchlin wrote an important text on this, De Arte Cabbalistica. Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa expanded Christian Kabbalah. He used it to explore ancient philosophy and science in his work De occulta philosophia libri tres.

Early esoteric thinkers like Agrippa believed in an Earth-centered universe. But after Copernicus showed the Earth orbits the Sun, understanding of the cosmos changed. Giordano Bruno adopted Copernicus's ideas into esoteric thought. His ideas were seen as heresy by the Roman Catholic Church, and he was executed.

A different type of esoteric thought grew in Germany, called Naturphilosophie. It was influenced by ancient traditions and medieval Kabbalah. But it mainly looked to two sources: Biblical scripture and the natural world. The main person in this movement was Paracelsus. He used ideas from alchemy and folk magic to challenge the common medical practices of his time. He urged doctors to learn medicine by observing nature. Later, he also focused on religious questions. His work became very popular.

One person influenced by Paracelsus was Jacob Böhme. He started the Christian theosophy movement. Böhme tried to understand why evil exists. He believed God came from a deep mystery, the Ungrund. He also thought God had a wrathful core, surrounded by light and love. Even though German authorities condemned his ideas, they spread. They formed the basis for small religious groups like the Philadelphian Society in England.

From 1614 to 1616, three Rosicrucian Manifestos were published in Germany. These texts claimed to be from a secret brotherhood founded by Christian Rosenkreutz. There's no proof that Rosenkreutz or the group existed before this. The manifestos were likely written by theologian Johann Valentin Andreae. But they sparked a lot of public interest. Many people started calling themselves "Rosicrucian" and claimed to have secret esoteric knowledge.

A real secret group, Freemasonry, started in Scotland in the late 1500s. It grew from medieval stonemason guilds. It soon spread across Europe. In England, Freemasonry became more focused on humanism and reason. But in France, it adopted new esoteric ideas, especially from Christian theosophy.

18th, 19th, and Early 20th Centuries

The Age of Enlightenment brought more secular governments and a focus on science and reason. This led to a "modernist occult" movement. Esoteric thinkers found new ways to deal with these changes. One such person was Emanuel Swedenborg. He tried to combine science and religion after seeing a vision of Jesus Christ. He wrote about his travels to heaven and hell and talking with angels. He believed the visible world mirrors an invisible spiritual world, with connections between them. After he died, his followers started the Swedenborgian New Church. His writings also influenced many other esoteric ideas.

Another important figure was Franz Anton Mesmer. He developed the idea of Animal Magnetism, later called Mesmerism. Mesmer claimed a universal life force flowed through everything, including humans. He believed illnesses were caused by blocks in this force. He created techniques to clear these blocks and restore health. One of Mesmer's followers, the Marquis de Puységur, found that Mesmerism could cause a trance state. In this state, people claimed to see visions and talk to spirits.

These trance states greatly influenced Spiritualism. This esoteric religion started in the United States in the 1840s and spread widely. Spiritualism was based on the idea that people could talk to the spirits of the dead during séances. Most Spiritualism was practical, but some developed full religious ideas. The scientific interest in Spiritualism led to the study of psychical research. Trance states also influenced early psychology and psychiatry. Esoteric ideas were in the work of early figures like Carl Gustav Jung. However, later psychology moved away from esotericism. Also influenced by artificial trance was the religion of New Thought. It was founded by Phineas P. Quimby. It focused on "mind over matter"—believing that belief could cure illness.

In Europe, a movement called occultism emerged. People tried to find a "third way" between Christianity and science. They built on ancient, medieval, and Renaissance esoteric ideas. In France, after the 1789 Revolution, figures like Éliphas Lévi and Papus were influenced by traditional Catholicism. René Guénon developed an occult idea called Traditionalism. He believed in an original, universal tradition and rejected modern ways. His ideas influenced later esotericists like Julius Evola.

In English-speaking countries, the growing occult movement was often anti-Christian. It saw wisdom coming from Europe's pre-Christian pagan religions. Many Spiritualist mediums became unhappy with existing esoteric thought. They looked for inspiration in older ideas. Helena Blavatsky called for a return to the "occult science" of the ancients. She said it could be found in both East and West. She wrote Isis Unveiled (1877) and The Secret Doctrine (1888). In 1875, she co-founded the Theosophical Society. Later leaders of the Society, Annie Besant and Charles Webster Leadbeater, saw modern theosophy as a form of Christian esotericism. They even declared Jiddu Krishnamurti as a world messiah. In response, Rudolf Steiner founded the Anthroposophical Society. Another form of esoteric Christianity is the spiritual science of the Danish mystic Martinus.

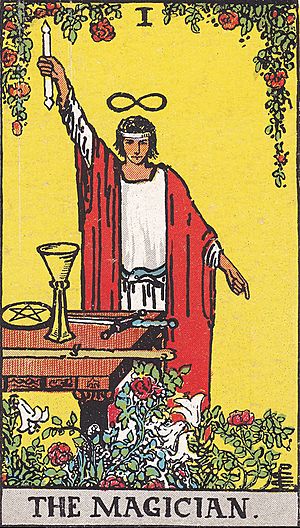

New esoteric ideas about magic also developed in the late 1800s. One pioneer was Paschal Beverly Randolph. In England, the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn was founded. It was a secret group focused on magic based on Kabbalah. Aleister Crowley was a member. He later started the religion of Thelema. Other thinkers like George Gurdjieff and P.D. Ouspensky developed esoteric ideas without magic.

Occult and esoteric systems became more popular in the early 1900s, especially in Western Europe. Secret societies grew among European thinkers who had left traditional Christianity. The spread of secret teachings and magic found many followers in Germany between the World Wars. Writers like Guido von List spread neo-pagan, nationalist ideas. Many wealthy Germans joined secret societies like the Thule Society. Some members of the Nazi Party, like Alfred Rosenberg and Rudolf Hess, were linked to the Thule Society. Adolf Hitler's mentor, Dietrich Eckart, was also a guest. After they came to power, the Nazis persecuted occultists. While many Nazi leaders like Hitler were against occultism, Heinrich Himmler used Karl Maria Wiligut as a clairvoyant. Wiligut helped set up symbols and ceremonies for the SS. However, by 1939, Wiligut was removed from the SS because he was institutionalized for mental illness. The German magic order Fraternitas Saturni was founded in 1928. It was banned by the Nazis in 1936. Its leaders left Germany to avoid prison. After World War II, the Fraternitas Saturni reformed.

Some scholars, like Hugh Urban, see Scientology as a modern form of Western Esotericism.

Later 20th Century and Today

In the 1960s and 1970s, esotericism became linked with the growing counter-culture in the West. People felt they were part of a spiritual revolution, marking the Age of Aquarius. By the 1980s, these ideas were known as the New Age movement. It became more commercial as businesses saw a market for spiritual products. However, some esoteric ideas kept their anti-commercial and counter-cultural spirit. This included the techno-shamanic movement by figures like Terence McKenna.

This time also saw the growth of modern Paganism. This movement was first led by Wicca, a religion started by Gerald Gardner. Wicca was adopted by feminists, especially Starhawk, and grew into the Goddess movement. Wicca also influenced Pagan neo-druidry and other Celtic revival groups. In response to Wicca, some groups started calling themselves followers of "traditional witchcraft." They claimed older roots than Gardner's system.

Since the 1990s, countries in the former Iron Curtain have seen a rise in different religions. Many occult and new religious movements have become popular. Gnostic revivalists, New Age groups, and Scientology splinter groups have spread in the former Soviet bloc. This happened after the Soviet Union broke apart. In Hungary, many people practice or follow new Western Esotericism. In 1997, the Fifth Esoteric Spiritual Forum was held there and was full. Later that year, the International Shaman Expo began. It was broadcast live on TV for two months. Many neo-Shamanist, Millenarian, mystic, neo-Pagan, and even UFO religion groups attended.

Studying Western Esotericism

The academic study of Western esotericism began in the early 1900s. Historians realized that pre-Christian and non-rational ideas had a big impact on European society. This was true even though earlier scholars had ignored them. The Warburg Institute in London was a key place for this study. Scholars like Frances Yates argued that esoteric thought had a greater effect on Renaissance culture than previously thought. Yates's 1964 book, Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, was very important. It helped bring more attention to how esoteric ideas influenced modern science.

In 1965, the Sorbonne created the world's first university position for studying esotericism. It was called the "History of Christian Esotericism." François Secret was the first to hold this position. In 1979, Antoine Faivre took over. The position was renamed "History of Esoteric and Mystical Currents in Modern and Contemporary Europe." Faivre is credited with making the study of Western esotericism a formal field. His 1992 work L'ésotérisme is seen as the start of this academic field.

Faivre noted two big challenges for this field. First, there was a bias against esotericism in universities. Many thought it wasn't worth studying. Second, esotericism crosses many subjects. It didn't fit neatly into one field. As Wouter J. Hanegraaff said, Western esotericism must be studied separately from religion, philosophy, science, and art. This is because it "participates in all these fields" but doesn't fit perfectly into any. He also said there was "probably no other domain in the humanities that has been so seriously neglected."

In 1999, the University of Amsterdam created a position for the "History of Hermetic Philosophy and Related Currents." Hanegraaff held this position. In 2005, the University of Exeter created a position in "Western Esotericism." Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke took this role. By 2008, there were three university positions dedicated to the subject. Amsterdam and Exeter also offered master's degree programs. A journal, Aries: Journal for the Study of Western Esotericism, started in 2001. Also in 2001, the North American Association for the Study of Esotericism (ASE) was founded. The European Society for the Study of Western Esotericism (ESSWE) was created soon after.

Within a few years, it became an established field in religious studies. Scholars from other areas of religious studies started to show interest.

|

See also

In Spanish: Esoterismo occidental para niños

In Spanish: Esoterismo occidental para niños

- Black magic

- Ceremonial magic

- Eastern esotericism

- English Qaballa

- Medieval European magic

- Medieval Inquisition

- Renaissance magic

- White magic

- Witch trials in the early modern period