Lawrence Bragg facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Lawrence Bragg

|

|

|---|---|

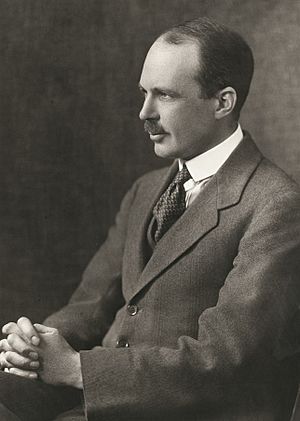

Bragg in 1915

|

|

| 3rd Director of the National Physical Laboratory | |

| In office 1937–1938 |

|

| Preceded by | Frank Edward Smith (acting) |

| Succeeded by | Charles Galton Darwin |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

William Lawrence Bragg

31 March 1890 Adelaide, Colony of South Australia |

| Died | 1 July 1971 (aged 81) Ipswich, England, UK |

| Education |

|

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | Bragg's law (1913) |

| Title |

|

| Spouse(s) |

Alice Hopkinson

(m. 1921) |

| Children | 4, including Stephen |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives | Charles Todd (grandfather) |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | X-ray crystallography |

| Institutions |

|

| Academic advisors |

|

| Doctoral students |

|

| Other notable students |

|

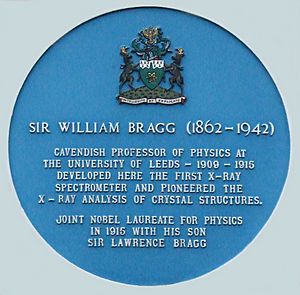

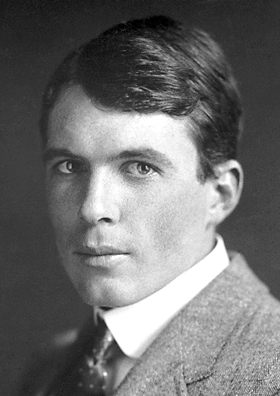

Sir William Lawrence Bragg was a brilliant British physicist, born on March 31, 1890, and passed away on July 1, 1971. He is famous for sharing the 1915 Nobel Prize in Physics with his father, William Henry Bragg. They won for their amazing work on understanding crystal structure using X-ray crystallography. This was a huge step in science!

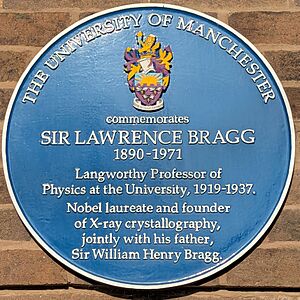

Lawrence Bragg was incredibly young when he won the Nobel Prize – just 25 years old. As of 2025, he is still the youngest person ever to win a Nobel Prize in any science field. Later, he led the Cavendish Laboratory at Cambridge. It was there, under his leadership, that James D. Watson and Francis Crick discovered the famous structure of DNA in 1953.

Contents

Learning and Early Life

William Lawrence Bragg was born in Adelaide, South Australia. His father, William Henry Bragg, was a professor of mathematics and physics at the University of Adelaide. His mother, Gwendoline, was the daughter of Charles Todd, a government astronomer.

Lawrence went to Queen's School, North Adelaide and then St Peter's College, Adelaide. At just 16, he started studying mathematics, chemistry, and physics at the University of Adelaide, finishing in 1908. That same year, his family moved to England because his father became a professor at the University of Leeds.

In 1909, Bragg began studying at the University of Cambridge at Trinity College, Cambridge. He was very good at mathematics, even taking an exam while sick with pneumonia and still earning a scholarship! Later, he switched to physics and graduated with top honors in 1911. In 1914, he became a Fellow of Trinity College.

Besides his studies, Bragg loved collecting seashells. He gathered specimens from about 500 different species in South Australia. He even discovered a new type of cuttlefish, which was named Sepia braggi after him!

Scientific Discoveries and Career

Understanding Crystals with X-rays

In 1912, while he was a young research student at Cambridge, Lawrence Bragg had a brilliant idea. He realized that when X-rays hit a crystal, they would bounce off the layers of atoms inside. If the X-rays hit at just the right angle, they would reflect in a way that created a clear pattern on a film. This pattern could then be used to figure out how the atoms were arranged in the crystal.

He developed a simple but powerful formula called the Bragg equation. This equation connects the wavelength of the X-ray, the distance between the atomic layers in the crystal, and the angles at which the X-rays would reflect.

His father built a special machine called an X-ray spectrometer. With this, they could rotate a crystal and measure the reflected X-rays. Together, they measured the distances between atomic layers in many simple crystals. This work was crucial for understanding the hidden structures of materials. Lawrence wished his contribution was more clearly recognized in early reports.

Helping During Wartime

When World War I began, Bragg joined the Royal Horse Artillery. In 1915, he was asked to help the Royal Engineers develop a way to find enemy artillery. The challenge was that big guns made very low-frequency sounds, hard for microphones to pick up.

Sadly, his brother died during the war in 1915. Soon after, Lawrence and his father received the Nobel Prize in Physics. Lawrence was only 25, making him the youngest science Nobel winner ever.

After much hard work, Bragg and his team invented a special "hot wire air wave detector." This device could detect the low-frequency sounds of distant guns. This new method, called sound ranging, was very effective. The British Army used it, and later, the Americans adopted it too. For his important contributions during the war, he received the Military Cross and was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE).

He also served as an adviser during World War II, where his sound ranging methods were still used.

Leading Research Labs

Between the two World Wars, from 1919 to 1937, Bragg worked as a professor of physics at the Victoria University of Manchester. He then became the director of the National Physical Laboratory in 1937.

After World War II, Bragg returned to Cambridge and led the famous Cavendish Laboratory. He believed that the best research teams were small, with about six to twelve scientists.

He supported a young researcher named Max Perutz, who was studying large biological molecules like hemoglobin. This work was paused during the war, but after it, Bragg helped secure funding for Perutz's research.

Bragg was honored with a knighthood in 1941, becoming Sir Lawrence. After his father passed away in 1942, he continued to contribute to scientific efforts. He also helped create the International Union of Crystallography and became its first president.

The Discovery of DNA

One of the most exciting events during Bragg's time at the Cavendish Laboratory was the discovery of the structure of DNA. He encouraged and supported the work of James Watson and Francis Crick. In 1953, they announced that DNA had a double helix shape, which was a monumental breakthrough in biology.

Bragg shared this amazing news at a scientific conference in Belgium in April 1953. He later gave a public talk in London, which led to a newspaper article titled "Why You Are You. Nearer Secret of Life." This helped share the news with the public.

He nominated Crick, Watson, and Maurice Wilkins for the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Wilkins' award recognized the important X-ray work done by scientists at King's College London, including Rosalind Franklin. Franklin's famous "photograph 51" was key to showing DNA's double helix structure. Sadly, she passed away before the prize was awarded.

At the Royal Institution

In 1953, Sir Lawrence and Lady Bragg moved to the Royal Institution in London, where his father had also worked. He had given lectures there before and now took on a leadership role. He worked hard to strengthen the Institution, bringing in support from companies and hosting special events.

He also started popular "Schools' Lectures" for young people, using exciting demonstrations to teach about science, like electricity.

Bragg continued his research, focusing on understanding the structures of complex molecules. For example, in 1965, scientists at the Royal Institution, led by David Chilton Phillips, solved the structure of an enzyme called lysozyme. This was another big achievement in understanding how biological molecules work.

His work helped X-ray analysis become a widely used method for studying proteins. Many Nobel Prizes have been awarded for discoveries made using this technique. He retired in 1966.

Personal Life and Hobbies

In 1921, Lawrence Bragg married Alice Hopkinson. They had four children: Stephen Lawrence, David William, Margaret Alice, and Patience Mary. Alice was also very active in public life and worked on important social issues. She even served as the Mayor of Cambridge from 1945 to 1946.

Bragg enjoyed many hobbies, including drawing, painting, reading, and especially gardening. He loved gardening so much that when he moved to London and didn't have his own garden, he secretly worked as a part-time gardener for someone else!

Sir Lawrence Bragg passed away on July 1, 1971, at the age of 81. He is buried at Trinity College, Cambridge.

Awards and Recognition

Lawrence Bragg received many honors for his scientific contributions:

- He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1921, which is a very high honor for scientists.

- He was knighted by King George VI in 1941, becoming Sir Lawrence.

- He received prestigious awards like the Copley Medal and the Royal Medal from the Royal Society.

- From 1939 to 1943, he was the President of the Institute of Physics in London.

- In 1967, Queen Elizabeth II appointed him a Member of the Order of the Companions of Honour.

To remember his legacy, the Institute of Physics has awarded the Lawrence Bragg Medal and Prize since 1967. Also, the Australian Institute of Physics awards the Bragg Gold Medal for Excellence in Physics to top PhD students in Australia, honoring both Lawrence and his father.

Here are some of his major awards:

- Nobel Prize in Physics (1915)

- Matteucci Medal (1915)

- Hughes Medal (1931)

- Dalton Medal (1942)

- Royal Medal (1946)

- Copley Medal (1966)

An area in South Australia, the Electoral district of Bragg, was named after both William and Lawrence Bragg in 1970.

See also

In Spanish: William Lawrence Bragg para niños

In Spanish: William Lawrence Bragg para niños

- List of Nobel laureates in Physics

- Tactical artillery terms from World War I

- Tube Alloys

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |