William Monroe Trotter facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

William Monroe Trotter

|

|

|---|---|

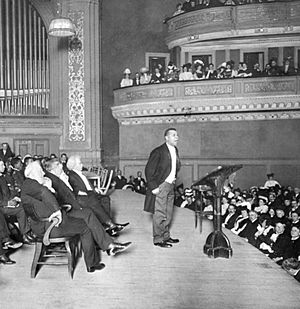

1915 photograph

|

|

| Born |

William Monroe Trotter

April 7, 1872 near Chillicothe, Ohio, U.S.

|

| Died | April 7, 1934 (aged 62) Boston, Massachusetts

|

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

| Spouse(s) | Geraldine "Deenie" Pindell |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Civil rights, real estate |

| Institutions | Boston Guardian |

| Influences | James Monroe Trotter (father), William Lloyd Garrison |

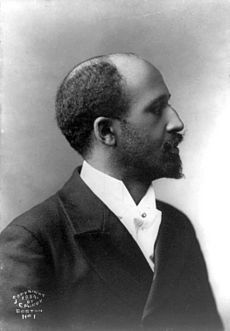

William Monroe Trotter (April 7, 1872 – April 7, 1934) was an important American civil rights activist. He was also a newspaper editor and a real estate businessman in Boston, Massachusetts. Trotter strongly disagreed with the ideas of Booker T. Washington, another leading African-American figure. Washington believed in a slower approach to gaining equal rights, focusing on economic progress first.

In 1901, Trotter started the Boston Guardian newspaper. He used it to speak out against racial inequality and push for immediate civil rights for African Americans. He was active in many protest movements in the early 1900s. He also helped create the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), a major civil rights organization.

Trotter came from a wealthy family and grew up in Hyde Park, Massachusetts. He went to Harvard University and was the first Black man to earn a Phi Beta Kappa key there, which is a sign of excellent academic achievement. As he saw more segregation happening, even in the North, he decided to dedicate his life to activism. He joined W. E. B. Du Bois to form the Niagara Movement in 1905. This group was a step towards the NAACP. Trotter's strong opinions sometimes caused disagreements, and he later left the Niagara Movement to lead the National Equal Rights League.

In 1914, Trotter had a famous meeting with President Woodrow Wilson. He protested Wilson's decision to separate Black and white workers in federal government offices. Trotter also worked to stop racist plays and movies. He died on his 62nd birthday.

Contents

Early Life and Education

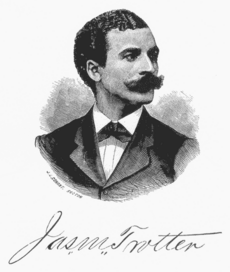

William Monroe Trotter was the third child of James Monroe Trotter and Virginia (Isaacs) Trotter. He was the first of their children to live past infancy. His father, James, was born into slavery in Mississippi. James's mother and her children were freed by their owner and moved to Cincinnati, Ohio. Cincinnati had a strong community of free Black people. James Trotter later joined the United States Colored Troops during the American Civil War. He was the first Black man to become a lieutenant in the 55th Regiment of the Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry.

Virginia Isaacs, William's mother, was also of mixed race and born free in 1842. Her mother was born into slavery at Monticello, the home of Thomas Jefferson. Virginia's father bought her mother's freedom. The family moved to Chillicothe, Ohio, where Virginia grew up in a lively Black community. There, she met and married James Trotter.

After the Civil War, the Trotter family moved from Ohio to Boston, Massachusetts. William Monroe Trotter was born on April 7, 1872, when his parents briefly returned to Virginia's family farm in Ohio. When he was seven months old, the family moved back to Boston. They lived in the South End and later in Hyde Park, which was a mostly white neighborhood.

William's father, James, faced and overcame many racial barriers. He often spoke out against unfair treatment. While in the army, he protested unequal pay for Black and white soldiers. In Boston, he was the first Black man to work for the United States Post Office Department. He left this job because he was repeatedly denied promotions due to unfair policies. James Trotter was also active in politics. He was a leading Black Democrat in New England. In 1886, he was appointed Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia. This was the highest federal position held by Black men at that time. This job paid well, and the Trotter family lived comfortably.

Young William, often called "Monroe," grew up in this environment. He met Archibald Grimké, another active Black leader who lived nearby. Monroe was an excellent student. He graduated from Hyde Park High School as the top student and class president. He then went to Harvard University, where he continued to do very well. He received scholarships after his father died. He was the first Black man to earn a Phi Beta Kappa key at Harvard, which shows high academic achievement. He earned his bachelor's degree in 1895 and his master's degree in 1896. He worked many small jobs to pay for his studies.

While at Harvard, he was also active in the Baptist church and even thought about becoming a minister.

Marriage and Early Career

After graduating, Trotter became part of the upper-class Black society in Boston. Many members of this group had ancestors who were free before the Civil War. He joined a special literary club that met at the home of educator Maria Louise Baldwin. On June 27, 1899, Trotter married Geraldine Louise ("Deenie") Pindell. She came from another activist family and had known Trotter since childhood. She helped him throughout his career until she died in the 1918 flu pandemic. They did not have any children.

Trotter's first jobs were not very successful. He tried to get jobs at banks and real estate companies but couldn't. He ended up with lower-paying office jobs. In 1898, he finally got a job at a white-owned real estate firm. But the next year, he decided to open his own business selling insurance and arranging mortgages. During these years, he wasn't very active in civil rights. However, his strong beliefs about racial equality were clear in a paper he wrote in 1899. In it, he urged Black Americans to seek higher education. At that time, many people tried to steer Black Americans away from college towards industrial training. Trotter's business did well enough for him to buy properties for investment.

Trotter became more and more concerned about the ideas of Booker T. Washington. Washington was a very important Black leader in the 1890s and founded the Tuskegee Institute. Washington's approach was called the Atlanta Compromise. In a famous speech in 1895, he suggested that Black Americans in the South should not demand political rights, like the right to vote or equal treatment, if they were given economic opportunities and basic legal rights. Washington believed that once Black Americans proved they were productive members of society, they would gain full political rights.

Trotter, Grimké, W. E. B. Du Bois, and other activists in the North disagreed. They argued that Black Americans needed to fight for equal treatment and full constitutional rights right away. They believed this would bring other benefits. By the early 1900s, Black Americans in the South had largely lost their right to vote due to violence and new voting rules.

Boston was more welcoming than other parts of the country. But Trotter and others felt that Washington's ideas were causing more racist attitudes to spread, even in Boston. Trotter wrote that he worried his business success could be at risk "if race prejudice and persecution and public discrimination from mere color was to spread up from the South."

The Guardian Newspaper

My vocation has been to wage a crusade against... disenfranchisement, peonage, public segregation, injustice, denial of service in public places for color, in war time and peace.

Trotter's activism grew stronger in 1901. He helped start the Boston Literary and Historical Association, which became a place for strong opinions on race. He also joined the Massachusetts Racial Protective Association, another local group working for equality. Through this group, Trotter gave his first big protest speech in October 1901. He attacked Washington's approach, saying, "Washington's attitude has ever been one of servility."

In 1901, Trotter co-founded The Guardian, a weekly newspaper, with George W. Forbes. Trotter paid for the newspaper and was its managing editor. Forbes, who had experience in publishing, handled the daily operations. The Guardian became a place for a more direct and strong way to achieve racial equality. Its articles and editorials, mostly written by Trotter, often criticized Washington. Other Black newspapers criticized the Guardian for its strong stance.

The Guardian did not have a huge number of readers, but it was very important. It was one of only about 200 Black publications in the country. The newspaper struggled financially because Trotter was not good at managing money and was busy with other things. Forbes left the business in 1904 because of legal challenges from Booker T. Washington's supporters. Trotter's wife and later his sister helped him publish the paper.

The Guardian was bitter, satirical, and personal; but it was earnest, and it published facts. It attracted wide attention among colored people; it circulated among them all over the country; it was quoted and discussed. I did not wholly agree with the Guardian, and indeed only a few Negroes did, but nearly all read it and were influenced by it.

In 1907, Trotter deliberately moved the Guardian's offices to the same building that once housed William Lloyd Garrison's Liberator. Trotter greatly admired Garrison, who was a leading activist against slavery before the Civil War. Trotter studied Garrison's methods and often wrote to Garrison's sons.

The Guardian was never profitable. By 1910, Trotter sold all his properties in Boston to get money for the newspaper. He was also not strict about collecting payments from his readers. In his later years, the newspaper's quality went down. A local community group had to raise money to keep it going.

Challenging the Establishment

In the early 1900s, Trotter noticed that racial segregation was increasing in Boston. More hotels, restaurants, and other public places were refusing service to Black Americans. He realized that to make real change, his strong message needed to go beyond Boston. So, he started organizing protest meetings across New England in 1903.

His main goal was to change the policies of the National Afro-American Council. This was the only national organization for Black Americans at the time. At the group's yearly meeting in Louisville, Kentucky, Trotter and others proposed ideas for more activism. But supporters of Booker T. Washington, who controlled the council, voted against them. The Guardian newspaper said the meeting was "dominated to death by one man." However, the actions of Trotter and his group at the meeting did get them some national attention. Trotter kept criticizing Washington in the Guardian. His attacks were very strong and personal, making the disagreement very bitter.

During this time, the Great Migration of Black Americans from the South to the North was beginning. Black people in the two regions faced different situations. Most Black Americans still lived in the South, many in rural areas. They had lost their right to vote due to new laws and state constitutions. This situation would continue for many decades. Washington believed he had to help this population within their difficult environment. He also secretly paid for legal challenges against voting restrictions. Trotter and other activists usually came from the North. There, Black Americans had more rights, including the right to vote. They lived more in cities and had achieved more in work and education, but they still faced discrimination.

After failing to push their ideas in Louisville, Trotter and his group looked for another way to challenge Booker T. Washington. An opportunity came when Washington was scheduled to speak in Boston in July 1903. When Washington was introduced to a hostile crowd, a commotion started. Trotter, who had prepared several challenging questions for Washington, tried to read them over the noise. He was among those arrested, and the "Boston riot" was reported in newspapers across the country. Trotter later said there was no plan to break up the meeting. Washington's supporters pressed charges against Trotter for disturbing the meeting. Trotter was defended by Archibald Grimké. He was found guilty and spent thirty days in jail. Even though Washington's supporters hoped to discredit Trotter, the trial actually gave him more publicity. After the trial, Trotter founded the Boston Suffrage League in 1903. When a New England Suffrage League was formed in 1904, Trotter was elected its president.

Washington fought back against Trotter's attacks in several ways. He took legal action against Trotter, including a libel lawsuit and criminal charges. He also used his network to pressure Trotter's supporters at their jobs. Washington also had people secretly attend and report on activist meetings organized by Trotter. He also helped fund other newspapers in Boston to counter Trotter's strong voice. Because of these actions, Trotter's printer stopped working with him. But Trotter found another printer and continued to publish the Guardian.

Niagara Movement and the NAACP

In early 1905, Booker T. Washington tried to create a large organization to include all major Black leaders. W. E. B. Du Bois and Archibald Grimké were two of the most radical leaders invited. However, both refused to join Washington, feeling he would control the group too much. Du Bois, Trotter, and two others organized a meeting of activists from across the country. They met in July just across the border in Fort Erie, Ontario, Canada. There, they founded the Niagara Movement. The group was set up so that no single person could control it. They created a strong statement of principles, written by Trotter and Du Bois. It called for fighting for equal economic opportunities and full civil rights for Black Americans. The organization soon faced internal disagreements and Washington worked against its growth from the outside.

In early 1906, disagreements started between Du Bois and Trotter about allowing women to join the organization. Du Bois supported it, and Trotter was against it, but he eventually agreed. The issue was resolved during the 1906 meeting. Their differences became more serious when Trotter disagreed with Clement G. Morgan, a long-time supporter and Movement member, over Massachusetts politics and control of the local Movement chapter. Du Bois sided with Morgan. When the Movement met in Boston in 1907, Du Bois reappointed Morgan to a leading position. Attempts to fix the disagreement failed, and Trotter resigned from the Movement. Because of these problems, the organization had mostly fallen apart by 1908. The break between Trotter and Du Bois was permanent, and they never worked together directly again. Du Bois wrote in 1909 that it was "utterly impossible to work with Mr. Trotter."

Even though the Niagara Movement failed, its goals appealed to white people who supported racial equality. These supporters helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). This new group brought together Black and white people. Trotter and Du Bois were both at meetings in 1909 where the NAACP was planned. Some of Trotter's ideas were accepted, like addressing segregated transportation. However, others were not. Trotter was not invited to be on the organization's executive committee. Booker T. Washington, who boycotted the effort, was also not invited.

Trotter never played a big role in the NAACP. In its early years, he actively competed with it. In 1911, Trotter's group and the NAACP both held rallies in Boston to celebrate the 100th birthday of abolitionist Charles Sumner. Trotter was involved with the NAACP for a few years, but he did not like how much white people were involved in the group. His disagreement with Du Bois was deep, so he rarely contributed to the NAACP at the national level. He was also concerned by the attitudes in the Boston chapter. He told NAACP leader Joel Elias Spingarn that it needed more "radical, courageous activity." He eventually drifted away from the NAACP.

National Equal Rights League

After Trotter left the Niagara Movement, he helped organize a meeting of like-minded activists in Philadelphia in April 1908. He was the chairman of this meeting. In this role, he did not allow anyone to attend whose racial ideas he opposed. He also excluded those who supported Republican William Howard Taft in the upcoming 1908 United States presidential election. Trotter opposed Taft because he was tired of what he saw as the Republican Party's hands-off approach to race issues. This meeting led to the formation of the Negro-American Political League, which later became known as the National Equal Rights League (NERL). Trotter described this group as "of the colored people and for the colored people and led by the colored people."

NERL, which one writer called Trotter's "personal fief," could not attract famous members like the NAACP did. Trotter did not want white members and found it hard to work with other Black leaders. NERL and the NAACP, while both working towards similar goals, often argued with each other.

As the NAACP gained more money and talented people, it became the main center for civil rights activities that opposed Booker T. Washington. Trotter and the NERL became less important. Trotter would not have such a prominent role in the civil rights discussion again. By 1921, the League had shrunk to only a few of Trotter's supporters.

Trotter and President Wilson

Trotter's opposition to Booker T. Washington put him at odds with Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft. These Republican presidents relied on Washington for advice and had wide support from Black Americans. Trotter supported the Southern Democrat Woodrow Wilson in the 1912 election. Wilson met briefly with Trotter and other NERL members and made vague promises about fair treatment for Black Americans. However, Wilson gave in to pressure from Southerners in his cabinet and agreed to separate federal offices by race.

The NAACP and NERL protested this decision. Trotter arranged a meeting with Wilson at the White House in November 1913. Wilson claimed his policies were not segregationist, but Trotter called Wilson's denial "preposterous" (meaning absurd or ridiculous).

Trotter continued his protests and got a second invitation to the White House in November 1914. This meeting with Wilson ended with a heated argument. Wilson said he was dealing with a "human problem" that should be kept separate from politics. He suggested that Trotter's group could always vote for someone else in the next election. Trotter continued to argue that the segregation policy was humiliating for Black Americans. Wilson responded, "If you take it as a humiliation, which it is not intended as, and sow the seed of that impression all over the country, why the consequences will be very serious." After Trotter said this was an insult, Wilson angrily told him to leave. He said, "If this organization wishes to approach me again, it must choose another spokesman... your tone, sir, offends me."

Trotter's second meeting with the President was widely reported in the news. It was on the front page of The New York Times and other major newspapers. A white Texas newspaper described Trotter as "not a Booker T. Washington type of colored man." Northern papers also criticized him for being "insolent" (rude or disrespectful) to the president. The Boston Evening Transcript agreed that Wilson's policy was segregationist. It also noted that while Trotter was mostly right, he "offends many of his own color by his... untactful belligerency." Black Americans had mixed reactions to the incident. Some said he did not represent them, while others, like Du Bois, admired Trotter's boldness. Du Bois wrote that Wilson was "insulting & condescending" in the meeting. Trotter used the publicity to give a series of speeches. In them, he denied being "impudent, insolent, or insulting to the President."

Trotter continued to protest the Wilson administration's segregation policies. When the country began recruiting many soldiers for World War I, Trotter opposed creating separate officer training facilities for Black soldiers. Because of his influence, fewer Black men enlisted in the Boston area than expected. During World War II, the military integrated its officer corps. Later, President Harry S. Truman fully integrated the armed services.

When World War I ended, Trotter wanted to use the 1919 Paris Peace Conference to raise international awareness of how the U.S. government treated Black Americans. He felt that segregation did not fit with Wilson's goal to "make the world safe for Democracy." Trotter organized a meeting in Washington, DC about the peace conference. He and ten other Black delegates were chosen to attend. However, the State Department refused to give passports to these delegates. They also refused passports to Black Americans planning to attend a Pan-African Congress that Du Bois was organizing in Paris at the same time.

To get to Europe, Trotter pretended to be a seaman looking for work in New York. He got a job as a cook on the SS Yarmouth to travel to France. He arrived in Paris alone, with little more than his cook's clothes. He found that the main peace talks had already happened. The world powers did not include any statement about racial equality. Trotter attracted the French press with his stories of racial mistreatment in the United States. However, he could not get access to any of the official delegations at the peace conference. He also missed Du Bois' Pan-African Congress, which was held in February 1919 while he was still trying to get passage.

Trotter returned to the United States in July 1919. He learned about race riots happening in major cities across the country. After the war, economic and social tensions had exploded. Black people fought back against white violence in cities like Chicago and Omaha. Trotter quickly supported active resistance to white violence against Black people. He wrote, "Unless the white American behaves, he will find that in teaching our boys to fight for him he was starting something that he will not be able to stop." His writings led to calls in Congress for censoring Black newspapers. South Carolina Congressman James F. Byrnes accused Trotter of "doing his utmost to incite riots and bloodshed." Massachusetts Senator Henry Cabot Lodge gave Trotter a chance to speak during Senate discussions about the Treaty of Versailles. Lodge opposed the treaty for other reasons than Trotter's. Lodge's opposition was successful, and the Senate never approved the treaty.

Later Protests and Years

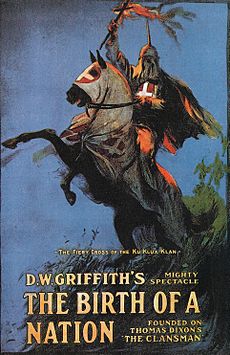

Trotter led a campaign against Thomas Dixon's play The Clansman when it opened in Boston in 1910. The play showed the Ku Klux Klan as heroes during the Reconstruction era. His protests succeeded in closing the production. While on a speaking tour in early 1915, he learned that D. W. Griffith's movie, The Birth of a Nation, which was based on The Clansman, would open in Boston. He quickly returned to lead protests against the film. In April, the Tremont Theatre refused to sell tickets to Trotter and a group of Black Americans. When they refused to leave the lobby, police moved in. Trotter and ten others were arrested. Other protests happened both inside and outside the theater. Trotter, working with other parts of the Black community, tried but could not get the film banned in Boston. This united effort, along with the death of Booker T. Washington later in 1915, temporarily reduced disagreements within Boston's Black community.

The KKK saw a revival for about ten years after 1915, especially in industrial cities. In 1921, Trotter successfully stopped new showings of The Birth of a Nation in Boston. He worked with Roman Catholic organizations, who also opposed the KKK's anti-Catholic views in the 20th century. These Catholic groups were strong in Boston due to many Irish and Italian immigrants.

Trotter's wife died in the 1918 influenza pandemic. She had been a partner in all his activities, and he missed her greatly.

Through the 1920s and 1930s, Trotter lived in quiet poverty. He continued to use the Guardian as a voice of protest.

In 1923, Trotter reached a difficult agreement with the NAACP. However, his efforts to promote his style of activism were overshadowed by younger leaders. One such leader was Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican immigrant in New York City and leader of the UNIA.

During these years, Trotter regularly wrote in the Guardian about cases of racial injustice.

William Monroe Trotter died on the morning of April 7, 1934, his 62nd birthday. He was buried in Boston's Fairview Cemetery.

Legacy and Honors

- Several schools and academic places were named after him: the William Monroe Trotter Elementary School in Dorchester, the William Monroe Trotter Institute at the University of Massachusetts Boston (a research center for Black history and culture), and the William Monroe Trotter Multicultural Center (also known as Trotter House) at the University of Michigan.

- Trotter's first home in Dorchester, the William Monroe Trotter House, was named a National Historic Landmark. This recognized his importance in the civil rights movement.

- In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante included William Monroe Trotter in his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |