1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery facts for kids

Quick facts for kids 1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery |

|

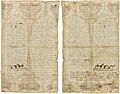

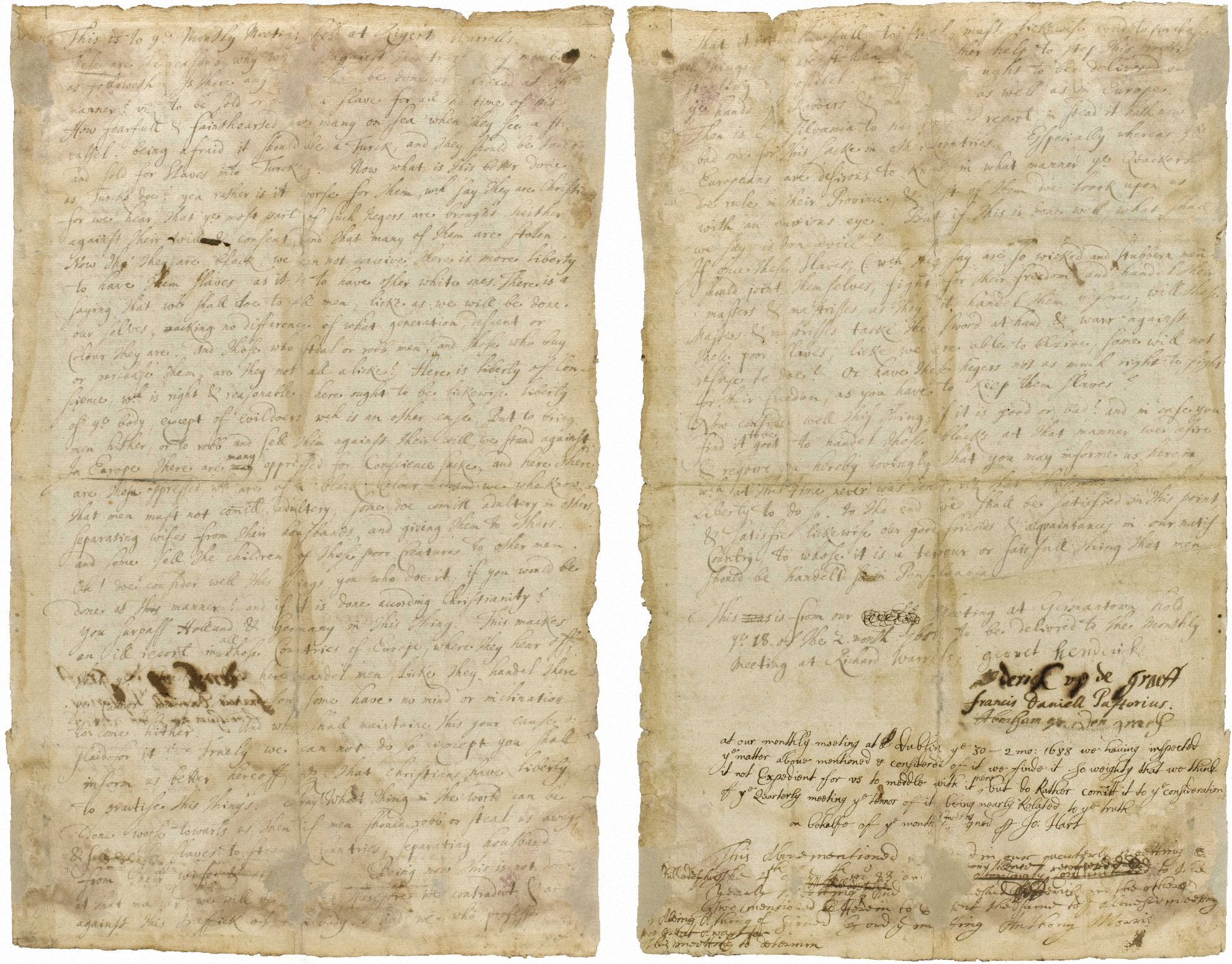

The petition was the first American public document to protest slavery. It was also one of the first written public declarations of universal human rights.

|

|

| Created | April 1688 |

| Location | Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections |

| Signers | Francis Daniel Pastorius, Garret Hendericks, Derick op den Graeff, and Abraham op den Graeff |

| Purpose | Protest against the institution of slavery. |

The 1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery was a very important document. It was the first time a religious group in the Thirteen Colonies officially protested against the enslavement of Africans. Francis Daniel Pastorius wrote this petition. He and three other Quakers from Germantown, Pennsylvania (which is now part of Philadelphia), signed it. They signed it for their local Quaker group, called the Germantown Meeting.

This document was quite controversial. The Quakers sent it up their leadership chain, from local to regional to yearly meetings. But none of these groups officially approved or rejected it. The petition then disappeared for 150 years! In 1844, a historian named Nathan Kite found it. Later, people who wanted to end slavery published it to help their cause.

Contents

Pennsylvania's Beginnings

The colony of Pennsylvania was started in 1682 by William Penn. He wanted it to be a place where people from any country or faith could live freely. They would not face religious persecution there. King Charles II gave Penn a large piece of land west of New Jersey to pay a debt. The King named this land Pennsylvania after Penn's father.

William Penn became a friend of George Fox, who started the Society of Friends. People often called them "Quakers" because they sometimes trembled during worship. Penn became a Quaker himself and was even put in jail for his beliefs. King Charles II let Penn create a special colony. Penn would choose the governor and judges. But the colony also had a democratic system. It offered freedom of religion, fair trials, elected representatives, and a clear separation of church and state.

Quakers in Europe

From 1660 to 1680, several Quakers, including William Penn, visited the Dutch Republic and the Rhine valley in what is now Germany. They held meetings and shared their Quaker beliefs. Many people, including some Mennonites from Krefeld and Kriegsheim, became Quakers.

One of these new Quakers was Francis Daniel Pastorius. He was a young German lawyer from a wealthy family. Pastorius felt that his job was not fulfilling. He wanted a purer life, free from the "sins of the European world." He was drawn to Penn's colony because it offered religious freedom. In Europe, Mennonites and Quakers were often fined or jailed. This was because they practiced a faith different from the official churches.

In 1681, Penn invited people from Europe to his new colony. He arrived in 1682. He had the land surveyed and planned Philadelphia as a welcoming city. It had a grid layout and many green spaces. Penn made money by selling land lots. Soon, the city was busy. Streets were laid out, houses were built, and churches for different faiths appeared. The city and nearby areas grew and became successful.

Germantown: A New Home

In 1683, Pastorius was asked to buy land in Pennsylvania. He was representing a group of men from Frankfurt who planned to move there. Pastorius traveled to Philadelphia in August 1683. He bought land from Penn's agent for the Frankfurt group.

In October 1683, thirteen German-Dutch families from Krefeld arrived. They had their own land claim. Pastorius saw a chance to create a German-speaking town. He worked with Penn to combine the two land claims. The Frankfurt Company people never actually moved to the colony. But more Quakers and Mennonites came from the Rhine valley. Pastorius's dream of a German-speaking town near Philadelphia came true.

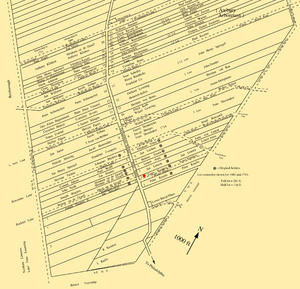

Pastorius designed a simple town plan. Lots were set up along one long main road where settlers could build homes. He needed land that was good for farming. This was because the new settlers would need to grow their own food. Pastorius and Penn became good friends. They often talked about plans for the new settlement.

The land Pastorius was promised was supposed to be flat and near a river. He had paid for 6,000 acres (24 km2) of connected land. But there was no suitable flat land near Philadelphia on the Delaware River. Most of it had already been sold. Penn suggested land near the Schuylkill Falls, but it was too steep. So, Penn suggested land a bit further east, on a gentle hill between two creeks. Pastorius agreed.

Germantown was founded along a Lenni Lenape trail. It was four miles (6 km) north of Philadelphia. The first families lived in downtown Philadelphia during the first winter. They worked hard to clear the land for their log houses. Germantown became a separate town with Dutch and German speakers.

The first thirteen Krefelder families were Mennonites who became Quakers in Holland. They had faced persecution for their beliefs. So, they understood how important a community based on religious toleration was. They were not rich, but they were skilled workers. They knew they would have to work hard. They were carpenters, weavers, dyers, tailors, and shoemakers. They were not fully ready for the hard work of clearing the forest. In their first year, they cleared land and planted crops. They also grew flax for weaving. They set up looms and soon made linen cloth. This cloth sold well throughout the colonies.

The Problem of Slavery

Some early settlers in Philadelphia and nearby towns were wealthy. They bought African slaves to work on their farms. Many of these slaveowners had also moved to escape religious persecution. But they did not see a problem with owning slaves themselves.

By 1500, serfdom (a type of forced labor) had ended in northwestern Europe. But other forms of servitude were still common. Many immigrants to the new colony were indentured servants. They agreed to work for several years to pay for their trip to the colony. Slavery was widespread in the American colonies. Local slave markets made it easy to buy slaves. The Atlantic slave trade was growing fast. Many settlers thought it was needed for the colonies' economy. Ship owners and captains made huge profits transporting slaves from Africa to the Caribbean and mainland North America. William Penn himself noted that Philadelphia had received ten slave ships in one year.

More Quaker and Mennonite families from Krisheim joined the first settlers in Germantown. They were German but spoke a similar language to the Krefelders. Some of them attended the local Quaker Meetings. These meetings were held in the new homes of immigrants. They became involved and accepted in the Philadelphia Quaker community. But in some ways, they still felt like outsiders. This allowed them to question the social values in the new colony. Some attended Quaker meetings temporarily. They waited for a Mennonite minister to arrive. Then they helped build the first Mennonite Meetinghouse. The town grew and became successful. A Quaker Meeting was organized at Thones Kunders's house. By 1686, a Quaker Meetinghouse was built near the current Germantown Friends Meeting.

The German-Dutch settlers were not used to owning slaves. They understood why slavery was used for economic success. Slaves and indentured servants were valuable because they were not paid. Yet, the German-Dutch settlers refused to buy slaves. They quickly saw that the slave trade and forced labor were wrong. In their home countries, only people convicted of a crime could be forced to work.

The Germantown settlers had a revolutionary idea. They saw a basic connection between being free from religious persecution and being free from forced labor. They believed everyone had the right to be free.

The Petition's Message

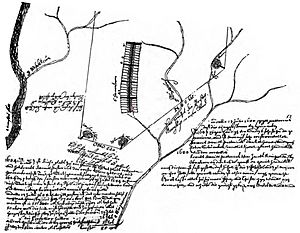

In 1688, five years after Germantown was founded, Pastorius and three other men wrote a petition. They gathered at Thones Kunders's house. Their petition was based on the Bible's Golden Rule: "Do unto others as you would have them do unto you." They urged the Quaker Meeting to abolish slavery.

This document was unusual. It did not start with a typical greeting to fellow Quakers. It also did not mention Jesus or God. Instead, it argued that every human, no matter their beliefs, color, or ethnicity, has rights that should not be violated.

The petition used the Golden Rule to argue against slavery and for universal human rights. At first, the argument might seem indirect. It did not directly ask the Meeting to condemn slavery. Instead, it used sarcasm. The men asked why Christians were allowed to buy and own slaves. They wanted slaveowners to see their own contradiction. This approach was very clever and effective. They strongly argued that in their society, capturing and selling people as slaves, separating families, would not be tolerated. Again, they referred to the Golden Rule.

The four men also said that slaves would have the right to revolt, according to the Golden Rule. They suggested that slavery would make it hard to attract new settlers. In the Caribbean colonies, there had been many slave revolts. So, the possibility was real. But the petition's point was deeper. Any slave revolt would be justified by the Golden Rule. This idea strengthened the concept of universal rights. These rights applied to all humans, not just "civilized" people. The petition used many strong arguments to challenge slave-owning readers.

The petition can be a bit hard to understand today. First, its grammar and spelling are old-fashioned. This shows the Krefelders' limited English and how spelling used to vary. For example, it uses "ye" for "the."

Second, the petition mentions Turks taking people into slavery. This refers to stories about Barbary pirates. These pirates operated from North Africa for hundreds of years. They attacked ships and captured slaves. Many Europeans were taken as slaves to North Africa or Turkey. Some English, French, and Germans paid to be freed. They brought back stories of these pirate attacks. When the petition was written, some Quakers were enslaved in Morocco. The petition used this comparison to make the Atlantic slave trade seem wrong. The authors believed slaves had social and political equality with free citizens.

Third, the petition uses the word "negers" for black slaves. In 1688, this German and Dutch word simply meant "black" or "negro." It was not meant to be offensive then. The petition shows respect for enslaved people and calls them equals.

The Petition's Impact

The four men presented their petition to the local Quaker Meeting. They were accepted by Quakers, but they were outsiders. They did not speak English perfectly. They also had a new view on slavery. They likely knew it would be hard to make the whole colony abolish slavery. Many believed the colony's success depended on it.

The local Meeting decided the issue was important and fair. But it was too difficult for them to judge. So, they sent it to the Philadelphia Quarterly Meeting. This group also sent it to the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting (PYM). The PYM met in Burlington, NJ. No Meeting wanted to make a decision on such a "weighty matter." The PYM recorded that they would send the petition to the London Yearly Meeting. But there is no proof they actually did. The London Yearly Meeting records do not mention the petition directly.

Slavery continued in Quaker society after 1688. Some authors of the petition kept protesting, but their efforts were rejected for a decade. Germantown continued to grow and prosper. It became known for its paper and woven cloth. Some of the original Krefelders later rejoined the Mennonites. They moved away from Germantown partly because they did not want to be associated with slave-owners.

Other Quaker petitions against slavery were written later. But many of these were based on racist or practical arguments. They often got mixed up with politics and religion. So, the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting dismissed them. It took almost 30 years for another Quaker petition to be as thoughtful as the 1688 Germantown one. But the Germantown settlers' strong stand against slavery influenced other Quakers and Philadelphia society.

Over the next century, many dedicated Quakers worked to end slavery. People like Benjamin Lay, John Woolman, and Anthony Benezet helped convince Quakers that slavery was wrong. Many Quaker abolitionists published articles in Benjamin Franklin's newspaper. In 1776, the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting banned slave ownership. By then, many Quaker meetings helped freed slaves. They gave money for businesses and encouraged education. Villages were set up, like in Lima, Pennsylvania, where freed slaves could settle with support.

Why This Document Matters

The 1688 petition was the first American document of its kind. It called for equal human rights for everyone. It pushed for higher standards of fairness and equality. This idea grew in Pennsylvania and other colonies. It led to the Declaration of Independence. It also influenced the abolitionist and suffrage movements. Later, Abraham Lincoln referred to human rights in the Gettysburg Address.

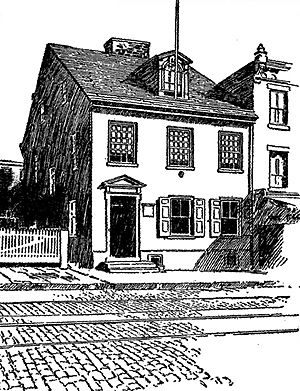

The 1688 petition was forgotten until 1844. When it was found, it became a key part of the growing movement to end slavery in the United States. After being public for a century, it was misplaced again. It was found once more in March 2005 at the Arch Street Meetinghouse.

At that time, the document was in bad shape. It had tears and old tape. Its ink was fading. To save it, experts at the Conservation Center for Art and Historic Artifacts (CCAHA) in Philadelphia worked on it. They removed old repairs and cleaned the paper. They fixed tears with special Japanese papers. Then, they photographed it and sealed it between clear films to protect it.

The petition was shown at an exhibit of rare American documents in 2007. Today, it is kept at Haverford College Quaker and Special Collections. The 1688 petition reminds us about the importance of freedom and equality for all people.

Images for kids

-

The Arch Street Friends Meeting House, where the original Petition Against Slavery was found again in 2005.

| Lonnie Johnson |

| Granville Woods |

| Lewis Howard Latimer |

| James West |