Australian Aboriginal religion and mythology facts for kids

Australian Aboriginal religion and mythology is about the special spiritual stories told by Indigenous Australians. These stories are shared in ceremonies by different language groups across Australia. Aboriginal spirituality includes ideas like the Dreamtime, songlines, and stories passed down orally.

These spiritual stories often describe the local land and its features. They give deeper meaning to Australia's landscape through oral history from ancestors. Many of these spiritual beliefs belong to specific groups, but some are known across the whole continent.

Contents

Ancient Stories and Science

A linguist named R. M. W. Dixon studied Aboriginal myths in their original languages. He found amazing links between details in some myths and what scientists discovered about the same places.

For example, on the Atherton Tableland, myths tell how Lake Eacham, Lake Barrine, and Lake Euramoo were formed. Scientists found that these lakes were created by volcanic explosions more than 10,000 years ago! Fossil pollen from the lake bottoms showed that when the craters formed, eucalyptus forests grew there, not the tropical rainforests we see today. This matches the Aboriginal stories.

Dixon realized that these myths about the Crater Lakes could be accurate for events that happened 10,000 years ago. Because of this, the Crater Lakes myth was added to Australia's Register of the National Estate and included in the wet tropical forests' World Heritage nomination. It's seen as an "unparalleled human record" of events from the Pleistocene era (Ice Age).

Dixon also found other Aboriginal myths that accurately describe ancient landscapes, including:

- The Port Phillip myth: This story says that Port Phillip Bay was once dry land, and the Yarra River flowed differently.

- The Great Barrier Reef coastline myth: This myth from Yarrabah tells of a past coastline at the edge of the current Great Barrier Reef. It even names places now underwater after the trees that used to grow there.

- The Lake Eyre myths: These stories say that the deserts of Central Australia were once fertile plains with lots of water, and the area around Lake Eyre was like a continuous garden. This matches what geologists know about a wet period in the early Holocene era, when the lake would have had permanent water.

Other ancient volcanic eruptions in Australia, like Mount Gambier and Kinrara, might also be recorded in Aboriginal myths.

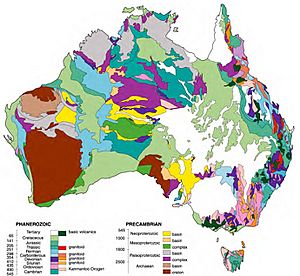

Aboriginal Mythology Across Australia

Aboriginal myths tell important truths about each group's local cultural landscape. They add deep meaning to the entire Australian continent. These stories share the wisdom and knowledge of Aboriginal ancestors from "time immemorial" (a very long time ago).

David Horton's Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia says that a "mythic map of Australia would show thousands of characters, varying in their importance, but all in some way connected with the land." Many of these characters could change shape, turning into humans, animals, plants, or natural features like rocks. They all left some of their spiritual essence in the places mentioned in their stories.

Australian Aboriginal mythologies are like a mix of a religious guide, a history book, a geography lesson, and a bit of a guide to the universe.

Many Different Stories

There are about 900 different Aboriginal groups in Australia. Each group has its own unique name, language, or way of speaking. Each language has its own myths, with special words and names.

Because there are so many different Aboriginal groups, languages, and beliefs, it's hard for experts to describe all the myths under one simple idea. However, The Encyclopaedia of Aboriginal Australia notes that there's a fascinating mix of differences and similarities in myths across the whole continent.

Learning About Aboriginal Views

The Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation created a booklet called Understanding Country. It helps non-Indigenous Australians learn about Aboriginal views on the environment. It says that Aboriginal myths:

- Generally describe the journeys of ancestral beings, often giant animals or people, over what was once a flat land.

- Mountains, rivers, waterholes, animals, plants, and other natural things came to be because of events during these Dreamtime journeys.

- Their existence in today's landscapes confirms these creation beliefs for many Indigenous peoples.

The paths taken by these Creator Beings across land and sea connect many sacred sites in a network of "Dreaming tracks" that criss-cross the country. These tracks can be hundreds or even thousands of kilometers long, from the desert to the coast. Different groups whose lands the tracks pass through often share these stories.

Myths and Society

Experts who study human societies suggest that Aboriginal myths help people understand their daily lives. They shape people's ideas and influence their behavior. These stories often include and "mythologize" historical events to serve these social purposes in a changing world.

It's a common belief that the Law (Aboriginal law) comes from ancestral peoples or Dreamings and is passed down through generations. The connection between the foundational Dreamings and certain landscapes is seen as eternal. People's rights to places are strongest when they feel a spiritual connection to one or more Dreamings of that place. The Dreaming is always there, while humans are temporary.

Aboriginal Views on Stories

Aboriginal experts believe that all Aboriginal myths across Australia, when put together, are like an unwritten (oral) library. Through these stories, Aboriginal people learn about the world and see a special Aboriginal "reality." This reality is based on ideas and values very different from those in Western societies.

Aboriginal people learned from their stories that society should be focused on the land, not just humans. This helps them remember their source and purpose. Humans can be exploitative if they don't remember they are connected to all creation. They are reminded that they are only here for a short time, and past and future generations must be considered.

People come and go, but the Land and its stories stay. This wisdom comes from a lifetime of listening, watching, and experiencing. There's a deep understanding of human nature and the environment. Some places hold "feelings" that can't be described physically. These are subtle feelings that resonate through the bodies of Aboriginal people. This is the "intangible reality" of these people.

Sacred Sites

Aboriginal people consider some places to be sacred. This is because these places are very important in the myths of the local people.

Myths Across Australia

Rainbow Serpent

In 1926, a British expert on Aboriginal cultures, Professor Alfred Radcliffe-Brown, noticed something interesting. Many Aboriginal groups across Australia seemed to share similar myths about a powerful, often creative, and sometimes dangerous snake or serpent. This huge snake was often linked to rainbows, rain, rivers, and deep waterholes.

Radcliffe-Brown called this common myth the 'Rainbow Serpent'. He found that the main character in this myth had different names in different places, like Kanmare, Tulloun, Kurreah, and Bunyip.

The 'Rainbow Serpent' is usually described as an enormous snake living in the deepest waterholes of Australia's waterways. It is believed to come from a larger being seen as a dark streak in the Milky Way. It appears to people as a rainbow when it moves through water and rain. It shapes landscapes, names places, and sings about them. It can also swallow and sometimes drown people. It can give knowledgeable people powers to make rain and heal, but it can also cause illness and death.

Even Australia's 'Bunyip' was identified as a type of 'Rainbow Serpent' myth. The term 'Rainbow Serpent' is now widely used by government groups, museums, art galleries, Aboriginal organizations, and the media. It refers to this specific pan-Australian Aboriginal myth and is also a general term for Australian Aboriginal mythology.

Captain Cook

Experts have also documented another common Aboriginal myth found across Australia. In these stories, a mythical, foreign (often English) character arrives from the sea. This character brings Western ways, sometimes offering gifts, but often causing great harm to the ancestors of the storytellers.

This main mythical character is often called "Captain Cook." This is a name shared with the wider Australian community, who also see James Cook as important in the colonization of Australia. However, in Aboriginal stories, Captain Cook is usually seen as a villain who brings British rule, and his arrival is not celebrated.

The many Aboriginal versions of Captain Cook are usually not direct memories of encounters with the real Lieutenant James Cook. The real James Cook explored and mapped Australia's east coast in 1770 on his ship, HM Bark Endeavour. The Guugu Yimithirr people did meet James Cook when his ship was being repaired near Cooktown. They even got some place names from this time.

However, the pan-Australian Captain Cook myth tells of a general, symbolic British character who arrives from across the oceans after the Aboriginal world was formed. This Captain Cook brings big changes to the social order, leading to the world that people live in today.

In 1988, anthropologist Kenneth Maddock collected several versions of this Captain Cook myth from different Aboriginal groups:

- Batemans Bay, New South Wales: Percy Mumbulla told how Captain Cook arrived on a big ship at Snapper Island. He came ashore and offered clothes and hard biscuits. But Mumbulla's ancestors threw the gifts into the sea.

- Cardwell, Queensland: Chloe Grant and Rosie Runaway said Captain Cook and his group seemed to rise from the sea with white skin, like returning ancestral spirits. He offered a pipe and tobacco (which was rejected as a "burning thing"), then boiled tea (rejected as "dirty water"), then baked flour (rejected as "stale"), and finally boiled beef (which tasted okay). Captain Cook then left, and the ancestors were sad to see the spirits depart.

- South-eastern Gulf of Carpentaria, Queensland: Rolly Gilbert told how Captain Cook sailed to Australia and tricked two of Rolly's ancestors into showing him the main camping area. After that, Europeans "shot people down, just like animal." Many old and young people were killed so Europeans could run their stock.

- Victoria River: A Captain Cook story says he sailed from London to Sydney to take land. He brought bullocks and men with firearms, leading to massacres of Aboriginal people in Sydney. He then went to Darwin and sent armed horsemen to hunt Aboriginal people in the Victoria River country. He set up Darwin and gave orders to police and cattle station managers on how to treat Aboriginal people.

- Kimberley: Many Aboriginal storytellers say Captain Cook is a European hero who landed in Australia. He used gunpowder and set a bad example for how Aboriginal people were treated. When he returned home, he claimed he hadn't seen any Aboriginal people and said the country was empty, so settlers could claim it. In this myth, Captain Cook introduced "Cook's Law," which settlers use. But Aboriginal people say this law is new, unfair, and false compared to Aboriginal law.

Views on Death

Aboriginal people's response to death might seem similar to European traditions, like holding a ceremony and mourning. However, the similarities are only on the surface. In death, Aboriginal spirituality focuses on the land. The deceased person is strongly linked to the land. "For Aboriginal people when a person dies some form of the persons spirit and also their bones go back to the country they were born in." They believe they share their being with their country. So, when a person dies, their country suffers, and trees might die or become scarred because they are believed to be connected to the deceased.

When an Aboriginal person dies, families have death ceremonies called "Sorry Business." During this time, the family and whole community mourn for days, crying and sharing their grief. Often, the deceased person's family stays together in one room to mourn.

It is often considered disrespectful to say a person's name after they die, as it might disturb their spirit. Photos of the deceased are also often not allowed for the same reason. A smoking ceremony might be done, using smoke on the belongings and in the home of the deceased. This is believed to help release the spirit. The cause of death, which is often seen as spiritual, might be determined by Aboriginal elders.

Ceremonies and mourning periods can last for days, weeks, or even months, depending on the person's social status. It is not culturally appropriate for a non-Aboriginal person to tell the family that someone has passed away. When someone dies, the family often moves out of their house, and another family moves in. Some families move to "sorry camps," which are usually further away. Mourning includes special chants, songs, dances, body paint, and cuts on the mourners' bodies. In some Aboriginal cultures, the body is placed on a raised platform for several months, covered in plants, or put in a cave or tree. When only the bones are left, family and friends scatter them or place them in a special spot.

Many Aboriginal people believe in a "Land of the Dead," also known as the "sky-world" (the sky). If certain rituals were done during their life and at their death, the deceased can enter this place. The spirit of the dead also becomes part of different lands and sites, making those areas sacred. This is why Aboriginal people protect their sacred sites.

The rituals performed allow an Aboriginal person to return to the "womb of all time," which is "Dreamtime." It connects the spirit to nature, ancestors, and their own meaning in life. "The Dreamtime is a return to the real existence for the Aborigine." Life is seen as a temporary phase, a gap in eternity. The experience of Dreamtime, through ritual or dreams, helps in daily life. The person who enters the Dreamtime feels connected to their ancestors. The strengths from the timeless past help with present needs. The future feels less uncertain because life is seen as a continuous link between past and future. Through Dreamtime, the limits of time and space are overcome. For Aboriginal people, dead relatives are still very much a part of life. It's believed that in dreams, dead relatives communicate their presence and can even bring healing. Death is seen as part of a life cycle: one emerges from Dreamtime through birth, returns to the timeless, and then emerges again. It's also a common belief that a person's spirit leaves their body during sleep and temporarily enters the Dreamtime.

Link to Astronomy

Many songlines include references to stars, planets, and the Moon. These complex systems of Australian Aboriginal astronomy also help with practical things, like navigation.

Stories of Specific Groups

Yolngu People

The Yolngu people have their own rich culture, law, and mythology.

Murrinh-Patha People

|

Murrinh-Patha people's country |

The Murrinh-Patha people, who live near Wadeye, have a Dreamtime that experts believe is a religious belief system as important as other major religions.

Scholars say the Murrinh-Patha have a strong unity in their thoughts, beliefs, and way of life. They see all parts of their lives and culture as being under the constant influence of their Dreaming. In this Aboriginal religion, there's no difference between spiritual and material things, or between sacred and everyday things. Instead, all life is 'sacred', all actions have 'moral' meaning, and all meaning in life comes from this eternal, ever-present Dreaming.

The natural world and the sacred world are perfectly matched. This means all of nature is filled with sacred meaning, and the sacred is everywhere in the physical landscape. Myths and mythic tracks cross thousands of miles, and every part of the land has a detailed 'story' behind it.

The Murrinh-Patha mythology is based on a philosophy that life is "a joyous thing with maggots at its centre." This means life is good, but there are many painful sufferings that each person must understand and go through as they grow. This is the main message in Murrinh-Patha myths. This philosophy gives the Murrinh-Patha people purpose and meaning in life.

For example, the following Murrinh-Patha myth is performed in ceremonies to initiate young men into adulthood:

- "A woman, Mutjinga (the 'Old Woman'), was in charge of young children. But instead of watching them, she swallowed them and tried to escape as a giant snake. The people followed her, spearing her and taking the undigested children from her body."

In this myth and its performance, young, uninitiated children must first be swallowed by an ancestral being (who turns into a giant snake), then brought back out. Only then are they accepted as young adults with all the rights and privileges that come with it.

Pintupi People

|

Pintupi people's country |

Experts who study the Pintupi people, who live in Australia's Gibson Desert, believe they have a very "mythic" way of thinking. For them, events happen and are explained by the pre-planned social structures and orders told in their superhuman mythology. They don't explain things by looking at the actions or decisions of individuals. This way of thinking effectively "erases" history.

The Dreaming provides a moral authority that is outside of individual choices and human creation. Even though the Dreaming, as an order of the universe, probably came from historical events, its origin is denied.

These human creations are seen as principles or examples for the immediate world. So, current actions are not understood as the result of human alliances, creations, and choices. Instead, they are seen as being controlled by a large, cosmic order.

In the Pintupi world view, three long geographical tracks of named places are very important. These are related chains of significant places named and created by mythical characters on their journeys through the Pintupi desert during the Dreaming. This complex mythology of stories, songs, and ceremonies is known to the Pintupi as Tingari. It is most fully told and performed by Pintupi people at larger gatherings in Pintupi country.

Newer Belief Systems

It's hard to know exactly how many Aboriginal people follow traditional beliefs compared to other religions like Christianity. The official census in Australia doesn't list traditional Aboriginal beliefs as a religion. Also, it often includes Torres Strait Islanders, who are a separate group of Indigenous Australians, in most counts.

In the 1991 census, almost 74% of Aboriginal people said they were Christian, up from 67% in 1986. The way the question was asked changed in 1991, and fewer people answered it. The 1996 census reported that almost 72% of Aboriginal people practiced some form of Christianity, and 16% said they had no religion. The 2001 census didn't have similar updated information.

A small number of Aboriginal people also follow other major religions.

Images for kids

-

The Djabugay language group's mythical being, Damarri, transformed into a mountain range, is seen lying on his back above the Barron River Gorge, looking upwards to the skies, within north-east Australia's wet tropical forested landscape.

See Also

In Spanish: Mitología aborigen australiana para niños

In Spanish: Mitología aborigen australiana para niños