Annexation of Santo Domingo facts for kids

|

Santo Domingo City

Watercolor by James E. Taylor 1871 |

|

| Date | 1869 – 1871 |

|---|---|

| Location | Washington, D.C. |

| Participants | United States, Dominican Republic |

| Outcome | Treaty defeated in the U.S. Senate - June 30, 1870 |

The annexation of Santo Domingo was a plan by the United States to take over the country now known as the Dominican Republic. This happened between 1869 and 1871. At that time, the Dominican Republic was often called "Santo Domingo."

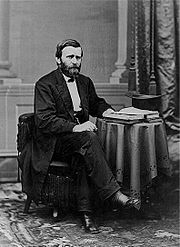

U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant started this plan. He wanted Santo Domingo to become a United States territory, with the chance to become a U.S. state later. President Grant was worried that European countries might try to take over the island. This would go against the Monroe Doctrine, a U.S. policy that warned European powers to stay out of the Americas. Grant also thought that owning Santo Domingo could help end slavery in places like Cuba. He also believed it could offer a new home for African Americans who faced unfair treatment in the U.S.

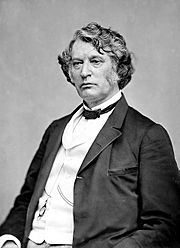

In 1869, President Grant sent his helper, Orville E. Babcock, to talk with the Dominican president, Buenaventura Báez. They worked on a treaty, which is a formal agreement between countries. However, this plan caused a lot of arguments in the U.S. Senate. Important senators like Charles Sumner and Carl Schurz strongly spoke against it. They said the treaty was only for the benefit of a few rich people.

While the treaty was being discussed, President Grant used the U.S. Navy to protect the Dominican Republic. This was to stop attacks from neighboring Haiti. President Báez in Santo Domingo believed his country would be safer and more successful as a U.S. protectorate (a country protected and partly controlled by a stronger one). He held a special vote, called a plebiscite, where almost everyone voted to join the U.S. Only 11 people voted against it. The Dominican Republic had a difficult past with many invasions and civil wars.

The treaty was written by Secretary of State Hamilton Fish. It said the U.S. would take over the Dominican Republic. It also included buying Samaná Bay for two million American dollars. This bay was important for ships. The treaty also said the Dominican Republic could apply to become a U.S. state.

When the treaty was discussed in the Senate, Senator Sumner strongly opposed it. He thought the plan was unfair and that the Dominican Republic was too unstable. He also believed President Báez was a bad leader. Sumner said that Grant's use of the U.S. Navy to protect Santo Domingo was against the law. He also worried that the U.S. might try to take over the entire island, including the independent black nation of Haiti. Senator Schurz also opposed the plan. He did not want people of different races to become U.S. citizens.

In the end, the treaty did not get enough votes to pass in the Senate. It needed two-thirds of the votes, but it ended in a tie. To try and prove that annexation was a good idea, Grant sent a special committee to investigate. This committee included the famous African American leader Frederick Douglass. Their report supported the idea of annexation. However, it still wasn't enough to change the Senate's mind.

The treaty failed because not many people outside of President Grant's close group supported it. This failure caused a big split in the Republican party. This split affected the presidential election of 1872. Grant's supporters were called Radical Republicans. His opponents, including Sumner and Schurz, formed the Liberal Republicans.

Contents

Why the U.S. Wanted Santo Domingo

Before President Grant, in 1867, the Dominican government had already asked the U.S. to annex them. They were worried about being invaded by Haiti. But the U.S. Congress at that time was not interested.

In April 1869, a businessman from New England, Joseph W. Fabens, spoke for the Dominican Republic. He asked Secretary of State Hamilton Fish if the U.S. would annex Santo Domingo. At first, President Grant wasn't very interested. But he changed his mind when he learned that the U.S. Navy wanted Samaná Bay. This bay would be a good place for ships to refuel.

Secretary Fish sent someone to check on the Dominican Republic's money problems and if its people truly wanted to join the U.S. But that person got sick. So, President Grant sent his helper, Orville E. Babcock, instead. Babcock was given a special letter from Grant to show President Báez.

President Grant saw that the Dominican Republic had many valuable resources. He believed it could create thousands of jobs for African American workers. It could also help U.S. farms and factories by increasing exports. Grant also thought that if African Americans from the Southern United States had a choice to move to the island, violent groups like the Ku Klux Klan in the South might stop their attacks. This was because they would not want to lose their cheap workers. However, Grant was careful not to openly suggest African Americans move there. He also worried that Britain might try to take control, so he stressed the importance of the Monroe Doctrine.

The Annexation Treaty

In September 1869, Babcock returned to Washington with a rough draft of the annexation treaty. President Grant's advisors were surprised because they didn't know Babcock was going to create a treaty. Grant asked Secretary Fish to write a formal treaty, as Babcock didn't have the official power to do so.

Secretary Fish was ready to quit because he hadn't been involved in the process. But Grant convinced him to stay. They agreed that Fish would support the Dominican annexation. In return, Grant would not support Cuban rebels during the Ten Years' War.

On October 19, 1869, Fish wrote the official treaty. It said the United States would annex the Dominican Republic. The U.S. would also pay $1,500,000 (which is about $35 million today) to help with the Dominican Republic's national debt. The treaty also offered the Dominican Republic the chance to become a U.S. state. Finally, the U.S. would rent Samaná Bay for $150,000 per year for 50 years. Grant's biographer, Jean Edward Smith, noted that Grant made a mistake by not getting public support and by keeping the treaty a secret from the Senate.

Grant and Senator Sumner

On January 2, 1870, before the treaty was officially sent to the Senate, President Grant did something unusual. He visited Senator Charles Sumner at his home in Washington, D.C.. Grant told Sumner about the treaty and hoped for his support. Sumner was a very powerful senator. He was the Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. His support was very important for the treaty to pass.

What exactly was said during their meeting has been debated ever since. Different people remember it differently. However, Grant left the meeting feeling hopeful, believing Sumner would support his plan. Sumner later said he only told Grant he was "a Republican and an Administration man," meaning he generally supported the president.

Treaty Fails in the Senate

On January 10, 1870, President Grant officially sent the treaty to the U.S. Senate. The treaty was delayed until Sumner's Foreign Relations Committee started discussions in mid-February 1870. Secretary Fish noticed that the Senate was not eager to pass anything started by the President. Many senators also opposed the idea of adding a nation with so many black and mixed-race people.

Sumner allowed the treaty to be discussed openly in his Committee. But he did not share his own opinion at first. However, on March 15, in a private meeting, Sumner's Committee voted against the treaty 5 to 2. On March 24, in another private meeting, Sumner strongly spoke against the treaty. He believed annexation would be too expensive. He also thought it would create an American empire in the Caribbean. He worried it would reduce the number of independent Hispanic and African republics in the Western Hemisphere.

President Grant met with many senators to try and get their support, but it didn't work. Grant refused to remove the part of the treaty that allowed the Dominican Republic to become a state.

Finally, on June 30, 1870, the Senate voted on the treaty. It was defeated by a tie vote of 28 to 28. Eighteen Republican senators joined Sumner to vote against the treaty.

| Vote to ratify the treaty | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| June 30, 1870 | Party | Total votes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Democratic | Republican | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yea | 0 | 28 | 28 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nay | 9 | 19 | 28 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Not Voting | 13 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

What Happened Next

President Grant was very angry that the treaty failed. He blamed Senator Sumner for its defeat. Grant believed Sumner had promised to support the treaty during their meeting. In response, Grant fired John Lothrop Motley, who was the U.S. Ambassador to Britain and a close friend of Sumner. Then, in March 1871, Grant used his influence to get his allies in the Senate to remove Sumner as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Grant also managed to get Congress to approve a special investigation. A group was sent to the Dominican Republic to see if annexation would be good for both countries. This group, sent in 1871, included the civil rights activist Frederick Douglass. Their report said that annexing the Dominican Republic would be a good idea for the United States. However, this report still didn't create enough support in the Senate to overcome the opposition. Also, the local vote in the Dominican Republic only included about 30% of the people who could vote. So, the whole plan might not have truly reflected what the people wanted.

See Also

- Dominican Republic–United States relations

- Ostend Manifesto

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |