Roscoe Conkling facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Roscoe Conkling

|

|

|---|---|

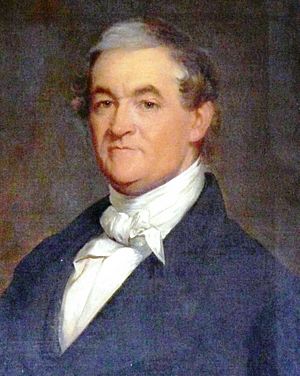

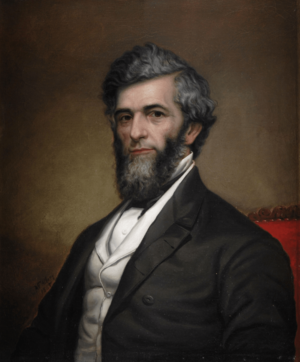

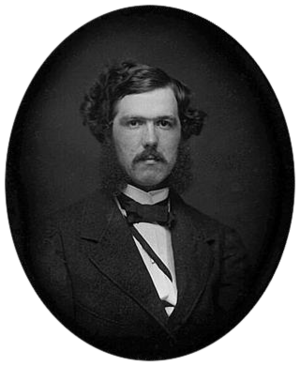

Senator Conkling, c. 1866-68

|

|

| United States Senator from New York |

|

| In office March 4, 1867 – May 16, 1881 |

|

| Preceded by | Ira Harris |

| Succeeded by | Elbridge Lapham |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New York |

|

| In office March 4, 1859 – March 3, 1863 |

|

| Preceded by | Orsamus Matteson |

| Succeeded by | Francis Kernan (redistricting) |

| Constituency | 20th district |

| In office March 4, 1865 – March 3, 1867 |

|

| Preceded by | Francis Kernan |

| Succeeded by | Alexander Bailey |

| Constituency | 21st district |

| Mayor of Utica | |

| In office March 9, 1858 – November 19, 1859 |

|

| Preceded by | Alrick Hubbell |

| Succeeded by | Charles Wilson |

| Oneida County District Attorney | |

| In office April 22, 1850 – December 31, 1850 |

|

| Preceded by | Calvert Comstock |

| Succeeded by | Samuel B. Garvin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 30, 1829 Albany, New York, U.S. |

| Died | April 18, 1888 (aged 58) New York, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | Forest Hill Cemetery Utica, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Whig (before 1854) Republican (1854–1888) |

| Spouse | Julia Seymour |

| Parents | Alfred Conkling Eliza Cockburn |

| Relatives | Frederick A. Conkling (brother) Alfred Conkling Coxe Sr. (nephew) |

| Signature |  |

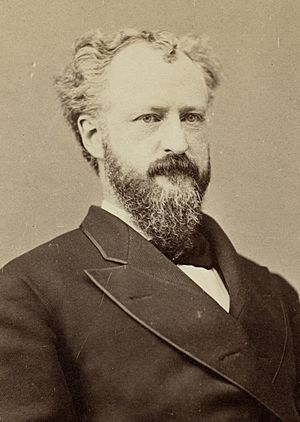

Roscoe Conkling (October 30, 1829 – April 18, 1888) was an American lawyer and Republican politician. He represented New York in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Senate. People remember him as a leader of the Republican Stalwart group. He was a very powerful figure in the Senate during the 1870s. Conkling was known for being physically fit. He exercised regularly and enjoyed boxing, which was unusual for his time. He also disliked tobacco.

While in the U.S. House, Conkling supported the Union during the American Civil War. He became a Senator in 1867. As a Radical Republican, he strongly supported equal rights for freed Black Americans. As a Senator, he became very powerful. This was because he controlled many government jobs (called patronage) at the New York Customs House. This port was one of the busiest in the world.

Conkling got along well with President Ulysses S. Grant. But he had conflicts with Presidents Rutherford B. Hayes and James A. Garfield. These conflicts were a big part of American politics in the 1870s and 1880s. Conkling openly opposed civil service reform. This reform aimed to make government jobs based on merit, not political favors. He called it "snivel service reform". He believed Senators should control who got appointed to jobs. This practice was often profitable and sometimes involved corruption.

His disagreement with President Garfield over appointments led to Conkling's resignation in 1881. He tried to get re-elected to show his power and support. But he lost the special election. This was likely due in part to President Garfield's assassination. Conkling never held elected office again. However, Garfield's death made Chester A. Arthur president. Arthur was a former New York Collector and a friend of Conkling. Their friendship ended when Arthur supported civil service reform. Arthur felt it was his duty to honor the late President Garfield. Conkling stayed active in politics and worked as a lawyer in New York City until he died in 1888.

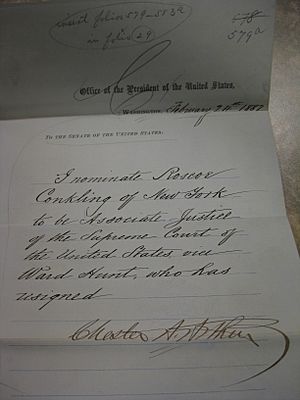

Conkling turned down two offers to join the U.S. Supreme Court. First, he declined the Chief Justice position in 1873. Then, he declined an associate justice role in 1882. In 1882, he first accepted the offer and was approved by the Senate. But he changed his mind and refused to serve. He was the last person (as of 2026) to do this.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Family Background

Roscoe Conkling was born on October 30, 1829, in Albany, New York. His father, Alfred Conkling, was a U.S. Representative and a federal judge. His mother was Eliza Cockburn. Her cousin was a famous judge in England, Sir Alexander Cockburn. Roscoe's father's family came to North America around 1635. They first settled in Salem, Massachusetts, then moved to Suffolk County, New York. Roscoe's mother's grandfather, James Cockburn, was from Scotland. He moved to the Bahamas and later to the Mohawk Valley. There, he married Margaret Frey, whose father was a powerful landowner.

Roscoe was the youngest of seven children. He had two older brothers, Frederick and Aurelian. Another brother, also named Roscoe, died before he was born. Both Roscoes were named after the British writer William Roscoe. Eliza Conkling enjoyed reading his books during her pregnancy. Roscoe's mother was known for her quick wit and brilliant conversations. Her son inherited these traits.

Childhood and Schooling

In 1839, the Conkling family moved to Auburn, New York. They traveled there using the Erie Canal. In Auburn, Roscoe loved horseback riding, which he continued to do his whole life. He wasn't very interested in schoolwork. But he had an amazing memory.

In 1842, Roscoe started at the Mount Washington Collegiate Institute in New York City. While there, he also studied public speaking with his older brother Frederick. They often practiced their speeches together. After a year, Roscoe went to the Auburn Academy for three years. Even as a schoolboy, Roscoe was impressive. His strong presence and intelligence made people pay attention. A childhood friend said Roscoe was "as large and massive in his mind as he was in his frame". He mastered his studies and social life, and his friends respected him.

Conkling first became interested in politics while at Auburn. His father was a leader in the Whig Party. Through him, Roscoe met many important people of that time. These included Presidents Martin Van Buren and John Quincy Adams. William Henry Seward, who lived in Auburn, was a friend of Conkling's father. Soon, Seward became a friend of Roscoe as well.

Starting a Law Career

In 1846, when he was seventeen, Conkling moved to Utica. He began studying law in the offices of Joshua A. Spencer and Francis Kernan. They were two of the best lawyers in the state. He became part of Utica society. He spoke publicly on many topics, especially supporting human rights and ending slavery. At eighteen, he spoke in Central New York to help those suffering from the Great Famine in Ireland. He strongly hated slavery. He called it "man's inhumanity to man". He called himself a "Seward Whig". He campaigned for Taylor and Fillmore in 1848.

Once, he wrote down a Henry Clay speech from memory so perfectly that Clay himself praised it. He also practiced public speaking by reciting parts of the Bible, Shakespeare, and British politicians. In 1849, Conkling got his first taste of political campaigning. He was chosen as a delegate for his party's meeting. He supported Joshua Spencer for a high court position.

Conkling became a lawyer in 1850. Soon after, Governor Hamilton Fish made him the temporary District Attorney for Oneida County. He was only twenty-one. He handled cases without help from older lawyers. He was nominated for re-election but lost. People mainly thought he was too young.

In 1852, Conkling started a law firm with Thomas R. Walker, a former Mayor of Utica. This partnership lasted until 1855. He became well-known in central New York. This happened after he defended Sylvester Hadcock in a forgery case. Conkling won by proving Hadcock could not read or write. In 1854, he won a case for a young woman who had been falsely accused. In 1855, he partnered with Montgomery Throop. This partnership lasted until 1862. He became one of the highest-paid lawyers in the area. He often charged over $100 per trial.

Until 1853, Conkling was a traditional Whig. In 1852, he campaigned in New York for General Winfield Scott. He criticized Franklin Pierce, saying Pierce supported slavery. As the Whig Party started to fall apart, Conkling helped form the Republican Party. He considered himself an "original Republican." In 1856, he spoke for John C. Frémont and William L. Dayton.

Mayor of Utica

In 1858, Republicans needed a candidate for Mayor of Utica. Utica was usually a Democratic city. The party chose Conkling on the first vote. After a five-day campaign, Conkling defeated Charles S. Wilson on March 2, 1858. He took office on March 9. He did not run for re-election. But he stayed mayor until he resigned on November 18, 1859. This was because the election to choose his replacement ended in a tie.

Serving in the U.S. House of Representatives

First Term in Congress

Right after being nominated for mayor, Conkling planned to run for Congress. The current Representative, Orsamus B. Matteson, was retiring. Conkling's main opponent was another Utica lawyer, Charles H. Doolittle. Conkling wanted to be elected because some people opposed his nomination. He campaigned as a friend of Senator Seward, who gave a speech for him. Conkling easily won his party's nomination.

Conkling's opponent in the main election was Judge P. Sheldon Root. Root refused to debate Conkling. Conkling campaigned alone. Conkling won the election by a good number of votes.

Conkling's first term as a Representative was quiet. He quietly opposed slavery. His speeches were mostly about legal topics. He supported John Sherman for Speaker of the House. On December 6, Conkling reportedly stood guard for Thaddeus Stevens. Stevens was criticizing Southern Representatives. People feared Stevens might be attacked. On April 17, 1860, Conkling gave a long speech. He attacked the Taney Court for its decisions on slavery. Conkling even said that Supreme Court decisions were only binding on lower courts.

In the second session of Congress, Conkling voted for a committee to deal with the growing crisis of states leaving the Union. He gave a speech against states leaving and against slavery. He voted for the Morrill Tariff. He voted against a proposed amendment that would have protected slavery.

Second Term and the Civil War

In the summer of 1860, Conkling campaigned for Abraham Lincoln and Hannibal Hamlin in New York. Conkling was disappointed that Seward wasn't nominated. But he spoke for Lincoln at a unity rally. Conkling was chosen again for Congress without anyone opposing him. He was re-elected by an even larger number of votes. As a new member of the House, he spent much of the 1860 campaign outside his own district.

President-elect Lincoln asked Conkling for advice on federal appointments. Conkling rejected a list from local Republicans. He told them, "Gentlemen, when I need your assistance... I shall let you know."

In 1861, Conkling worked with Chester A. Arthur and George W. Chadwick. They made money from wartime cotton. This business was successful and kept secret. Conkling later helped Arthur get appointed as a tax commissioner. Arthur was later appointed Collector of the Port of New York in 1871.

The 37th Congress met during the American Civil War, which started in April 1861. President Lincoln called Congress for a special meeting on Independence Day. This was to get an army ready. Conkling played a big role in this meeting. His older brother, Frederick, who was elected from Manhattan, joined him in the House. Conkling became the head of the Committee on the District of Columbia. He introduced a bill to create a watch group for Washington D.C. He also started a committee to look into a general bankruptcy law.

When Congress met again on December 3, 1861, Conkling asked the War Department to investigate a Union defeat. This was the Battle of Ball's Bluff. When George McClellan said an investigation would be bad for public service, Conkling gave a speech. He called the battle "the most atrocious military murder ever committed". This speech got national attention. His constant criticism led to the creation of a special committee. This committee oversaw the war effort.

Conkling always opposed printing paper money to pay for the war. He voted against the Legal Tender Act of 1862. He suggested selling bonds that could be paid back in gold instead. He continued to oppose increasing the money supply throughout his career.

Out of Office and Return to Congress

Conkling was nominated again by his party on September 26, 1862. He was opposed by his former law teacher, Francis Kernan. Kernan was running with his brother-in-law, Horatio Seymour, for Governor. Local Democrats used criticisms of Conkling against him. Some Republicans who were upset with Conkling also campaigned against him. He may have also lost votes because many Republican voters joined the Union Army. Also, more people were against the war. Conkling was narrowly defeated by Kernan by 98 votes. Seymour was elected Governor again.

After leaving office, Conkling went back to Utica and practiced law alone. He still gave public speeches sometimes. From 1863 to 1865, he worked informally for the War Department. He investigated claims of fraud in recruiting soldiers in western New York. In the summer of 1863, he and Kernan were opposing lawyers in a case about an Army deserter.

In 1864, Conkling strongly supported President Lincoln. He endorsed Lincoln's re-nomination and re-election. He refused requests to replace Lincoln with a more radical candidate. Conkling was nominated again by his party, despite some opposition. At the party meeting, Ward Hunt showed a letter from Lincoln. Lincoln said no other candidate "could be more satisfactory to me" than Conkling. He was nominated by a large vote but said no. A second vote was taken, and he accepted. In the fall election, with the war going better, Conkling defeated Kernan and got his seat back.

Before Conkling returned to the House, President Lincoln was inaugurated. The Civil War ended, and Lincoln was assassinated on April 14. Conkling and Seymour were part of the funeral procession from Albany to Utica.

Third Term and Key Issues

Conkling returned to Congress in December 1865. He was appointed to the powerful Committee on Ways and Means. He served with future Presidents Rutherford B. Hayes and James A. Garfield. He also served on the Joint Committee on Reconstruction. This committee wrote the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. He was one of the strongest supporters of giving freed slaves the right to vote.

Conkling's long rivalry with James G. Blaine started in his last term as a Representative. In April 1866, a bill was introduced to reorganize the army. It would have made the position of Provost-Marshal General permanent. Conkling opposed the bill. He said it would "create an unnecessary office for an undeserving public servant." He felt it would keep a "hateful instrument of war" in peacetime.

The current Provost-Marshal General, James B. Fry, responded through Blaine. Fry disagreed with Conkling's statement. He made specific accusations of wrongdoing against Conkling during his war-time legal service. These accusations were investigated. A committee found they had "no foundation in truth." But Conkling never forgave Blaine. Their personal dislike for each other affected Republican presidential politics for the next twenty years.

Conkling was re-elected over Palmer V. Kellogg in November 1866.

Serving in the U.S. Senate

Becoming a Senator

By December 1866, newspapers in New York suggested Conkling as the next Senator. Senator Ira Harris's term was ending in March. Conkling was seen as a young, modern choice. He secretly worked hard to get the seat. He studied the political situation in every county in New York. He gained the loyalty of local party leaders. The political group he built to become Senator later became the Stalwart faction of the Republican Party.

In the Republican meeting, Conkling was chosen over Noah Davis on the fifth vote. There were very few Democratic lawmakers in Albany. So, his election was almost guaranteed.

Conkling joined the Senate and became a member of several important committees. These included the Committees on Appropriations, the Judiciary, and Mines and Mining. He became popular with the press. Some even mentioned him as a possible candidate for president in 1868.

President Grant's Administration

Conkling strongly supported President Ulysses S. Grant and his policies. He was known as a key supporter of the Grant Administration.

During the Franco-Prussian War, Conkling supported Germany. He argued that Napoleon III had supported the Confederates in the Civil War. This made Napoleon III an enemy of the United States. Still, Conkling defended the administration. He argued against claims that they violated neutrality by selling weapons to France.

In 1870, New York elected its first Democratic legislature since the Civil War. This new legislature canceled its earlier vote to approve the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Conkling spoke out against this. He worked hard for the Civil Rights Act of 1875 to pass. He opposed attempts to weaken its rules.

In the 43rd United States Congress, Conkling opposed federal aid for the Boston Fire of 1872. He also opposed efforts to create a national system of bankruptcy law. He spoke against seating Republican Senator Alexander Caldwell of Kansas, who was accused of bribery and later resigned. He served on committees for Foreign Relations, Commerce, and the Judiciary. He also led the committee on revising laws.

In 1873, after the death of Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, President Grant asked Conkling to take the position. But Conkling said no. He stated, "I could not take the place, for I would be forever gnawing my chains." Instead, Grant nominated George Henry Williams, but the Senate rejected him. Conkling declined again, and Grant appointed Morrison Waite, who was approved.

Power Struggle with Reuben Fenton

In 1869, William H. Seward retired as Secretary of State. Senator Edwin D. Morgan was defeated. Suddenly, Senator Conkling became the most important Republican in New York. His new junior colleague, former Governor Reuben Fenton, quickly gained President Grant's attention. Fenton claimed to control presidential appointments in New York. Conkling and Fenton also disagreed on changes to a law about government jobs. Fenton wanted to cancel the law entirely.

Fenton's influence with Grant ended in 1870. Grant appointed Conkling’s choice, Thomas Murphy, as Collector of the Port of New York. Only Fenton and two other Republicans voted against this appointment. After this, Conkling had more influence with the Grant administration than almost any other Senator. At the 1870 state meeting, Conkling and his allies accused Fenton of a corrupt deal with Boss Tweed to control the New York City party. Many of Fenton’s supporters held easy jobs in city government. The Republicans lost the 1870 election badly. Conkling blamed Fenton's group for the loss.

In 1871, Conkling got Grant's support to change the New York City party organization. The state chairman removed Fenton's supporters. He started a new organization. This new group was led by Horace Greeley and Jackson S. Schultz. Greeley refused and joined Fenton’s group instead. This started a fight for power within the city party. The fight ended at the 1871 state meeting in Syracuse. Delegates voted to seat Conkling's group. The party platform supported President Grant and condemned "fraud and corruption in the city of New York." For the next ten years, Conkling was the clear leader of the New York Republican Party. Fenton eventually left the party in 1872. He supported the new Liberal Republican Party, which nominated Greeley for President against Grant.

President Hayes's Administration

Conkling and President Rutherford B. Hayes started off badly. Hayes named William M. Evarts as Secretary of State. Evarts was a New Yorker who opposed Conkling's political group. This appointment also stopped Conkling’s friend Thomas C. Platt from joining the cabinet. Only one cabinet member usually came from a state.

In April 1877, the Secretary of the Treasury, John Sherman, started an investigation. It looked into the New York Custom House. The investigation found many problems. It showed that federal office holders in New York were mostly political workers. Their jobs depended on their loyalty to New York City politicians.

After returning from Europe, Conkling became active in the 1877 New York state campaign. He and Platt openly criticized the Hayes administration. They passed resolutions supporting Grant. Conkling gave a long speech criticizing Hayes and praising Grant.

The conflict between Conkling and Hayes reached its peak in December 1877. Hayes nominated Theodore Roosevelt Sr. and L. Bradford Prince to replace Chester Arthur and Alonzo Cornell. They were to be the Collector and Naval Officer of the Port. These appointments were based on findings of corruption at the Port of New York. A commission of independent Republicans had found the corruption. The Senate rejected the nominations. After the vote, Conkling and Senator John Brown Gordon almost had a duel. But their friends stopped it.

Still, Hayes suspended Arthur and Cornell on July 11, 1878. He appointed Edwin Atkins Merritt and Silas W. Burt during the time Congress was not in session. Both were approved when Congress met again in February.

Garfield Administration and Resignation

Soon after James Garfield won the 1880 election, Conkling talked to friends about his future. He wanted to resign because of his disagreements with Garfield. But his friends urged him to stay. Garfield asked for his advice on "New York interests." He invited Conkling to visit him. Their private conversation remained a topic of debate for years.

Garfield chose James Blaine as Secretary of State. He also chose Thomas Lemuel James, a New York enemy of Conkling's, as Postmaster General. Garfield refused to appoint Conkling's choice, Levi P. Morton, for Secretary of the Treasury. Garfield further angered Conkling. He removed Edwin Atkins Merritt as Collector of the Port of New York. He appointed Judge William H. Robertson instead, at Blaine's urging.

Merritt's removal and Robertson's appointment made Conkling act. He resigned from the Senate. He wanted to prove his political strength. He also wanted to uphold the idea that Senators should have a say in appointments. Thomas C. Platt resigned with him.

Conkling personally attended the legislature's meetings in Albany. But Elbridge Lapham was chosen as his replacement. Any chance of Conkling's re-election ended when President Garfield was shot on July 2. The shooter, Charles Guiteau, was a fellow Stalwart. He had mentioned Blaine's appointment in threats to the President. Garfield was still alive when the election finished on July 22. But he died on September 19. Conkling's long-time friend, Chester Arthur, became president.

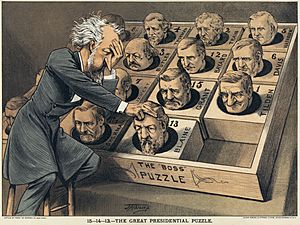

Presidential Politics

As a Senator and the leader of New York Republicans, Conkling was a "kingmaker." This meant he had a lot of power in choosing presidential candidates. He supported President Ulysses S. Grant in 1868 and 1872. In 1876, Conkling ran for president himself but lost. In 1880, he supported Grant for a third term.

Even though his chosen candidate didn't win, he successfully stopped a strong reformer from being nominated. Chester A. Arthur was nominated as vice president in 1880 to please Conkling. Arthur accepted, even though Conkling advised him not to. This led to Arthur becoming president after Garfield's assassination.

Supporting Grant in 1868 and 1872

Conkling actively supported Ulysses S. Grant's three presidential campaigns. In 1868, he campaigned for Grant against his own brother-in-law, Horatio Seymour.

As the 1872 campaign began, Conkling became one of the strongest defenders of the Grant administration. When Charles Sumner proposed a constitutional amendment to limit the presidency to one term in 1871, Conkling spoke against it.

Conkling led a speaking tour across New York state. It started in Manhattan on July 23. His speech there was used by the state party as a key part of the Republican campaign. Conkling spoke against Horace Greeley in personal terms. This drew criticism from Democratic and Liberal Republican newspapers. His next speech was on August 8. After that, he hosted a meeting with President Grant at his home in Utica. Grant easily won the election over Greeley. The Republican party won all of New York.

1876 Presidential Campaign

Soon after being re-elected to the Senate, Conkling became a top choice to succeed President Grant. He had Grant's support and the full backing of New York Republicans. A public meeting was held in Utica on March 2 to support his candidacy. The Republican state convention on March 22 endorsed Conkling for president. Conkling named Governor Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio as his second choice. This was likely to stop his rival James G. Blaine from winning the nomination.

At the Republican Convention in Cincinnati on June 14, the New York delegation worked hard to get Conkling nominated. His name was put forward by Stewart L. Woodford. Other candidates included James G. Blaine, Conkling’s rival, and Hayes.

Conkling's votes dropped after the first five ballots. Then, a delegate from Indiana started a rush to Hayes, who was nominated. New Yorker William A. Wheeler was nominated for vice president. Conkling promised to give four speeches for Hayes. But he only gave one, saying he was sick.

Conkling played an active role in solving the disputed election. Following President Grant's advice, he helped write and pass a bill. This bill created the Electoral Commission of 1877. This commission was to solve the dispute between Hayes and Samuel Tilden. He gave a powerful speech arguing for its legality. He said it would help avoid violence. But he refused to serve on the Committee himself. Conkling's own view was that neither Tilden nor Hayes should become president. This was often reported as him secretly supporting Tilden.

1880 Convention and Campaign

As the 1880 election neared, a movement grew to nominate President Grant for a third term. Conkling, along with Senators J. Donald Cameron and John A. Logan, led this movement. At the 1880 state convention, Conkling made sure New York's delegates promised to support Grant.

At the national convention, Conkling proposed that all delegates promise to support the final nominee. After James A. Garfield spoke against his proposal, Conkling wrote him a note. It said, "I congratulate you as being the 'dark horse.'" Conkling then withdrew his proposal.

On the fourth day, Conkling nominated Grant. Grant's strongest opponents were Conkling’s rivals, James G. Blaine and John Sherman. Sherman was nominated by James A. Garfield.

Conkling guided the Grant delegates through many votes. He never changed his belief that Grant should have a third term. On the fifth night, some delegates suggested Conkling himself could be nominated if he withdrew Grant’s name. He refused. The delegates who didn't support Grant struggled to find another candidate. It became clear the convention was split between pro-Grant and anti-Grant groups.

On the sixth day, James Garfield became the agreed-upon anti-Grant choice. He got enough votes on the thirty-sixth ballot. Conkling then moved to make his nomination unanimous. The Garfield campaign wanted a Stalwart for vice president. They first asked Levi P. Morton. Conkling advised Morton to decline, which he did. William Dennison Jr. asked Conkling for his choice for vice president. Conkling gave this choice to the New York delegation. They chose Chester Arthur over Stewart Woodford. The convention nominated Arthur on the first vote. Conkling advised Arthur to decline, but he did not.

During the general election campaign, Conkling noticeably avoided Garfield. He declined Garfield's invitations to meet. When Republican leaders met with Garfield, Conkling left his seat empty. When friends asked him why, he simply said, "There are some matters which must be attended to before I can enter the canvass." This comment was widely printed in newspapers. It suggested Garfield's position was weak.

Conkling only started campaigning actively after Grant and Arthur personally convinced him. Conkling gave a well-received speech in New York. Then he traveled west to give speeches in Ohio with President Grant. At the request of Grant and Senator Cameron, they stopped at Garfield’s home. During his entire visit, Conkling refused to be alone with Garfield. He gave four more speeches in Indiana. Then he returned to New York for the rest of the campaign.

Political Beliefs and Views

Conkling was a Radical Republican. He supported equal rights for former slaves. He wanted fewer rights for former Confederates. He helped create and pass laws for Reconstruction. This included the Civil Rights Act of 1875.

Conkling supported a plan to build a transcontinental telegraph to the Pacific Ocean. He also defended a broad interpretation of the ex post facto clause in the Constitution.

Money Policy

While in the House, Conkling disagreed with the Republican Party. He opposed the Legal Tender Act. This act created paper money to help fund the war. His brother, Frederick Augustus Conkling, joined him in this opposition. Both were "hard money" supporters. They argued that only precious metals (gold and silver) should be legal money. They believed the war could be won without increasing the country's debt. Instead, he argued for cutting government costs. This included reducing salaries and limiting travel expenses for Congress.

Conkling also strongly opposed the "inflation bill." This bill would have allowed an extra $46 million in bank notes. The bill passed, but President Grant vetoed it. A compromise was then reached. He actively opposed the Bland-Allison Act and any law that tried to increase the supply of silver.

Civil Rights and Women's Rights

Conkling was a lifelong supporter of civil rights for Black Americans. He continued to support Southern Reconstruction. This was even after it became less popular in the North. He supported it even after President Hayes decided to remove federal troops from Southern states.

In 1877, Conkling presented a petition. It was from citizens of New York, mostly women. It asked for an amendment to give all women the right to vote.

Later Life and Legacy

After leaving the Senate in 1881, Conkling went back to practicing law.

He was one of the original writers of the Fourteenth Amendment. In a Supreme Court case, Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad (1886), he claimed something important. He said the phrase "nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws" meant that corporations should be included. He said this because the word "person" was used. He even cited his personal diary from that time. A historian named Howard Jay Graham, an expert on the Fourteenth Amendment, called this the "conspiracy theory." He believed Conkling might have lied to help his railroad friends.

Relationship with President Arthur

Conkling and Arthur were very close. After President Garfield was assassinated, some feared that Conkling had arranged the killing. They thought he wanted Arthur to become president. This would bring back the system of political appointments based on favors. After Arthur became president in September 1881, Conkling tried to convince him to reverse Garfield's appointment of William H. Robertson. Arthur, who became a strong supporter of civil service reform, refused.

On February 24, 1882, Arthur nominated Conkling to be an associate justice of the Supreme Court. This was after Ward Hunt retired. Arthur sent the nomination to the Senate without knowing if Conkling would accept. The Senate approved him on March 2, 1882, by a vote of 39–12. But Conkling declined to serve in a letter to Arthur. He gave "reasons you would not fail to appreciate."

The friendship between Arthur and Conkling never healed. Without Conkling's leadership, his Stalwart group broke apart. However, when Arthur died in 1886, Conkling attended the funeral. People who saw him said he showed deep sadness.

Personal Life

During his first term as Senator, Conkling bought a large house in Utica. It remained his main home until he died. He decorated his walls with photos of famous people. These included Lord Byron, Daniel Webster, and Antonio López de Santa Anna.

Conkling loved reading poetry, especially the works of Lord Byron. He sometimes quoted or recited poetry in his speeches. He carefully studied British public speaking throughout his life. He particularly admired Thomas Babington Macaulay.

Conkling was a personal friend and political ally of Senator Blanche Bruce. He defended Bruce against critics. Bruce even named his son Roscoe Conkling Bruce in honor of their friendship.

Marriage and Family

Conkling married Julia Catherine Seymour on June 28, 1855. Julia was the sister of New York Governor Horatio Seymour. Horatio strongly opposed the marriage. He remained a strong political opponent of Conkling. Their marriage was not happy. Conkling focused on politics and was often distant from his wife.

Physical Fitness

Throughout his life, Conkling was known for his love of physical culture. This was an unusual hobby for a man of his time and social standing. Conkling kept his body fit by horseback riding and boxing. He took daily walks his whole life.

Stories about his boxing often appeared in newspapers. But it's not clear how accurate they were. Conkling was a big man (6’3”) and had a strong physical presence. This often drew attention from the press. Despite being proud of his body, Conkling had a strange dislike for "having his person touched."

In the summer of 1868, Conkling, Louis Agassiz, and others traveled to the Rocky Mountains. They visited Pike’s Peak. In his retirement, he became a governing member of the New York Athletic Club.

Death and Lasting Impact

On March 12, 1888, Conkling tried to walk three miles home from his law office on Wall Street. He walked through the Great Blizzard of 1888. Conkling only made it to Union Square before collapsing. He got pneumonia. Several weeks later, he developed an ear infection. After surgery to drain the infection, it spread to his brain, causing meningitis. Conkling died in the early morning hours of April 18, 1888. After leaving the Senate, Conkling had made up with his wife. Both his wife and daughter were with him when he died. Conkling is buried at Forest Hill Cemetery in Utica.

Conkling's Legacy

Roscoe Conkling's lasting impact is not very strong. He was a very important, interesting, and powerful politician in his time. But few lasting social or legislative achievements are linked to him. Chauncey Depew, a famous railroad executive and Senator from New York, commented on Conkling more than 30 years after his death. Depew said Conkling "was created by nature for a great career... he was the handsomest man of his time... his mental equipment nearly approached genius... [but] with all his oratorical power and his talent in debate, he made little impression on the country and none upon posterity... The reason for this was that his wonderful gifts were wholly devoted to partisan discussions and local issues."

A statue of him stands in Madison Square Park in New York City. Several places are named after Conkling. These include the towns of Roscoe, New York, Roscoe, South Dakota, and Roscoe, Georgia. Also, Roscoe Conkling Park in Utica, New York, is named for him. This park is 625 acres and has a zoo, golf course, and ski area. His house in Utica was made a National Historic Landmark in 1975.

Conkling was such a powerful politician that many babies were named after him. This was because people wanted to gain his favor. These names include Roscoe C. Patterson, Roscoe Conkling Oyer, Roscoe Conkling Bruce, and Roscoe C. McCulloch. However, Roscoe Conkling ("Fatty") Arbuckle's father disliked Conkling. He named his son that because he suspected the boy was not his own. He also knew about Conkling's reputation for having many relationships.

In Popular Culture

Conkling was an important character in Rosemary Simpson's 2017 detective novel What the Dead Leave Behind.

See also

In Spanish: Roscoe Conkling para niños

In Spanish: Roscoe Conkling para niños

- Seymour-Conkling family

| DeHart Hubbard |

| Wilma Rudolph |

| Jesse Owens |

| Jackie Joyner-Kersee |

| Major Taylor |