Antonin Raymond facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Antonín Raymond

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born |

Antonín Reimann

10 May 1888 Kladno, Kingdom of Bohemia, Austria-Hungary

|

| Died | 25 October 1976 (aged 88) Langhorne, Pennsylvania, U.S.

|

| Nationality | Czechoslovak, later American |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards | Medal of Honor by the New York Chapter of American Institute of Architects, The Third Order of Merit of the Rising Sun by Emperor Hirohito |

| Buildings | Reinanzaka House, Golconde Dormitory, Reader’s Digest Offices, Nanzan University |

Antonin Raymond (born Antonín Reimann on May 10, 1888 – October 25, 1976) was a famous Czech American architect. He was born and studied in Bohemia, which is now part of the Czech Republic. Later, he worked in the United States and Japan.

Raymond was also the Consul for Czechoslovakia in Japan from 1926 to 1939. This was a special role where he represented his home country.

His early work with American architects Cass Gilbert and Frank Lloyd Wright taught him a lot. He learned how to use concrete in new and interesting ways. Throughout his long career, he kept improving these skills.

In his studios in New Hope, Pennsylvania and Tokyo, he mixed old Japanese building ideas with the newest American methods. He used these ideas for many different projects. These included homes, businesses, churches, and schools. He built them in Japan, America, India, and the Philippines.

Many people see Raymond as one of the key figures in modern architecture in Japan. He shares this honor with British architect Josiah Conder.

Contents

- Antonin Raymond's Early Life

- Building in Japan Between the Wars

- The Golconde Dormitory in India

- The New Hope Experiment

- World War II Years

- Raymond & Rado

- The Reader's Digest Building

- New Ideas in Tokyo

- Noémi Raymond's Influence

- Raymond's Concrete Legacy

- Selected Works

- Awards

- See Also

- Images for kids

Antonin Raymond's Early Life

Antonin Raymond was born on May 10, 1888, in Kladno, Bohemia. This area is now part of the Czech Republic. His father was Alois Reimann, and his mother was Růžena.

After his mother passed away and his father's shop closed, his family moved to Prague in 1905. Raymond went to secondary school in Kladno and then in Prague.

In 1906, Raymond started studying at the Czech Polytechnic Institute. He finished his studies in Trieste in 1910. Soon after, he moved to New York City.

In New York, he worked for Cass Gilbert for three years. He helped design parts of famous buildings like the Woolworth Building. He also worked on the Austin, Nichols and Company Warehouse in Brooklyn. This work taught him a lot about how concrete could be used for building.

In 1912, he started studying painting. But he had to stop a painting trip to Italy because World War I began. On his way back to New York, he met Noémi Pernessin. They got married in 1914. In 1916, he became an American citizen and changed his name to Antonin Raymond.

Working with Frank Lloyd Wright

Raymond first saw Frank Lloyd Wright's work in 1908. He was very impressed by Wright's designs. Raymond felt that Wright had new ideas about how buildings should be made. He admired how Wright made spaces flow and blended buildings with nature.

In May 1916, Raymond started working for Frank Lloyd Wright. Raymond and Noémi first worked at Wright's home and studio, Taliesin, in Spring Green, Wisconsin.

In 1917, Raymond joined the United States Army. He served overseas during World War I. After the war, Wright asked him to come to Tokyo. He wanted Raymond to help him build the Imperial Hotel.

Raymond was Wright's main assistant for a year. However, he soon felt that Wright's design for the Imperial Hotel did not fit Japan. He thought it didn't suit the climate, traditions, or people. Also, Wright often covered concrete with brick, but Raymond saw more potential in concrete itself.

Raymond left Wright's team in January 1921. The next month, he started his own company in Tokyo. It was called the American Architectural and Engineering Company.

Building in Japan Between the Wars

Raymond's early work in Japan, like the Tokyo Woman's Christian College (started in 1924), still showed Wright's influence. It had low, sloped roofs and wide eaves, like Wright's "Prairie Houses." This work also showed his interest in Czech Cubism.

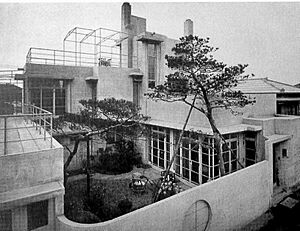

After their own house was destroyed in the Great Kantō earthquake, Raymond designed a new one. This was the Reinanzaka House in Azabu, Tokyo. He wanted to create his own style, different from Wright's. He explored how living, working, and dining areas could connect. He also used folding screens to close off spaces.

The Reinanzaka House was built mostly from concrete. Raymond's workers were excited about using this new material. They compared it to the strong walls of traditional Japanese storehouses called kura. The house also had metal windows and rain chains instead of drainpipes. Inside, it was very modern, with furniture made of steel tubes.

After some changes, his company was renamed Antonin Raymond, Architect.

Czechoslovak Consul in Japan

Even though he became an American citizen, Raymond also served as the honorary consul for the Czechoslovak Republic. This role gave him influence beyond just architecture. From 1928 to 1930, he designed and updated the American, Soviet, and French embassies.

He also worked for the Rising Sun Petroleum Company. He designed 17 earthquake-proof and fireproof homes for employees. He also designed their main office building, the manager's home, and two gas stations. All these buildings were in a modern style.

Inspired by Le Corbusier

Raymond became very interested in the work of Swiss architect Le Corbusier. In 1930, Kunio Maekawa joined Raymond's team. Maekawa had just worked for Le Corbusier in Paris. He brought many of Corbusier's ideas to the firm. Raymond then used these ideas with traditional Japanese architecture.

For example, he designed a summer house for himself in Karuizawa, Nagano. He based it on an unbuilt design by Le Corbusier for a house in Chile. Corbusier had used rough stone and a special roof. Raymond used cedar wood and a larch thatch roof, fitting the Japanese style.

In 1922, Raymond joined the Tokyo Golf Club. When the club moved in 1932, he was asked to design its new building. His connections to golfer Shiro Akaboshi also led to him designing several homes.

In 1937, Antonin, Noémi, and several Japanese architects, including Junzō Yoshimura, formed a new company in Tokyo. It was called Reymondo Kenchiku Sekkei Jimusho.

The Golconde Dormitory in India

In January 1938, Raymond, Noémi, and their son left Tokyo for America. Their six-month trip included visits to India and Europe, even a stop in Prague.

In 1935, Raymond's office was asked to design a dormitory for the Sri Aurobindo Ashram in Pondicherry, India. George Nakashima visited the site, and the first designs were ready in 1936. Raymond thought the building would take six months to build. However, Sri Aurobindo wanted the ashram residents to build it themselves to avoid noise.

Nakashima, Francois Sammer (another architect), and Chandulal (an engineer) first built a full-size model of the dormitory. This helped them test the design and improve building methods. Nakashima made very detailed drawings. Residents even donated brass cooking tools to be melted down for door handles and hinges.

Raymond designed the Golconde dormitory to suit the hot climate of Pondicherry. The main walls faced north and south to catch the cool breezes. It had movable window covers and sliding teak doors. This allowed air to flow through while keeping privacy. The building is still used today and was the first modernist building in India.

The New Hope Experiment

In 1939, Raymond started his architecture practice in the United States. He bought and changed a farm and studio in New Hope, Pennsylvania. He and his wife wanted to create a place that showed their modern design ideas. They wanted to mix new styles with traditional Japanese crafts. They hoped to live a simpler life, closer to nature, similar to Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin Fellowship.

The Raymonds changed their house to have an open layout. They used Japanese fusuma partitions and shōji screens to divide rooms. The rooms were filled with art, including rugs designed by Noémi.

Raymond invited young architects to come and live and study at New Hope. At least 20 students joined him. They learned practical design skills and also worked hands-on with building. They even helped with farm work. Famous visitors like Eero Saarinen and Alvar Aalto came to the farm.

Once the students were settled, Raymond found real projects for them. They worked on houses and additions in New Jersey, Connecticut, and Long Island.

In May 1943, the Raymonds helped George Nakashima and his family. They helped them leave a Japanese internment camp in Idaho so they could live at the New Hope farm.

World War II Years

As World War II approached, Raymond moved back to New York. The New Hope experiment ended. He started a new company with other engineers. Because the country was focused on the war, the company worked on projects for the US army.

Their work included building prefabricated houses at army camps in New Jersey and New York. In 1943, Raymond was asked to design Japanese-style homes. These homes were used by the Army to test how well building materials would stand up to different conditions. These houses were built at the Dugway Proving Ground, known as "Japanese Village." Raymond later said he was not proud of this work.

Raymond & Rado

After the war, Raymond started a new company with Slovak architect Ladislav Leland Rado. It was called Raymond & Rado. This company lasted until Raymond's death in 1976. However, Raymond worked mostly in Tokyo, and Rado worked in the New York office.

Raymond explored pottery and sculpture during this time. Rado focused on a more structured, logical design style.

Projects in the United States in the late 1940s helped Raymond get back to work in Japan. This helped restart building after the war. He used his old contacts and new ones from New York.

The Great River Station in New York showed Raymond's love for simple, cheap materials. It had stone walls and a flat roof supported by redwood posts. Large windows made it look like a modern glass building.

In the St. Joseph the Worker Chapel, Victorias, in the Philippines, Raymond worked with artist Ade Bethune. They created mosaic art and a special lacquerware tabernacle inside the concrete church. The church also had colorful paintings by Alfonso Ossorio. This church was a social center for sugar refinery workers. It is seen as one of the first modern church buildings in the Philippines.

The company also designed many parks and recreation buildings across the United States in the late 1940s. These were often built to celebrate the war victory.

The Reader's Digest Building

In 1947, Raymond asked General MacArthur for permission to return to Japan. He wanted to help rebuild the country after the war. His staff had kept his office drawings safe during the war, so Raymond reopened his office.

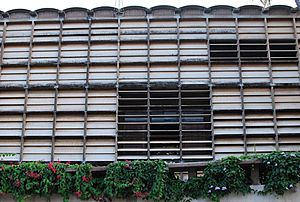

Raymond was asked to design the Reader's Digest Building in Tokyo in 1949. The company wanted a building that showed the best of American design. The building was planned for a site across from the Imperial Palace. Many Japanese people were upset because they felt this important site should have been a park.

Raymond responded by designing the building within beautiful gardens. He included sculptures by Japanese American artist Isamu Noguchi. The building was long and two stories tall. It had a unique frame supported by concrete columns that tilted outwards. Large windows on the second floor opened onto a balcony. It used new American ideas like sound-absorbing ceilings and special lighting.

This building is seen as the first large project where Raymond used his ideas of simplicity and light design. Raymond even said that the Hiroshima Peace Museum by Kenzo Tange looked similar to his Reader's Digest Building.

Even though it won awards, the Reader's Digest Building was torn down in 1963. A new, larger office building was built in its place.

New Ideas in Tokyo

Raymond bought land in the Nishi Azabu area of Tokyo. He built his new office and home there. The office used traditional Japanese post and beam construction with rough wooden logs. This office was a testing ground for new American building ideas. These included plywood and metal ducts for heating.

Raymond used the traditional Japanese ken (a unit based on the size of tatami mats) to plan the building. He used fusuma partitions and shoji screens in a modern way to divide spaces.

Raymond wanted to use the design of his office to create ideas for new homes. These homes would help rebuild Japan after the war.

In 1955, Raymond designed a Music Centre in Takasaki, Gunma. It was for the Gunma Symphony Orchestra. He wanted the building to be affordable and fit the historic site. He designed it with a simple structure, good views and sound for every seat, and a low roof. He achieved this using thin, reinforced concrete ribs that stretched 60 meters.

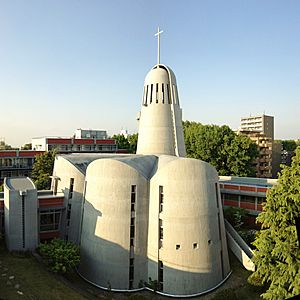

In 1961, he was asked to design the Catholic Nanzan University in Nagoya. This was one of his biggest projects. The campus was built on rolling hills, and its eight buildings were placed to fit the land. Concrete was used throughout the campus. Each building had its own concrete shape, some with columns and others with curved shells.

Near the Nanzan Campus is the Divine Word Seminary Chapel (1962). This building shows how flexible concrete can be. Two curved concrete shells form a bell tower. These shells have vertical openings that let light shine along the curved inner walls.

Noémi Raymond's Influence

Noémi Pernessin was born in 1889 in Cannes, France, to Swiss-French parents. She moved to New York in 1900. She studied Fine Art and Philosophy at Columbia Teachers College. There, she was inspired by artist Arthur Wesley Dow.

When Raymond was training as a painter, Noémi supported them. She did graphic design work for newspapers like the New York Sun. When they moved to Taliesin, she became interested in 3D design. She also learned a lot about Japanese crafts. She even helped clients like Rudolph Schindler's wife find Japanese art.

Noémi had a big influence on Raymond's work. She encouraged him to develop his own style, different from Wright's. She helped him explore the design of the Reinanzaka House. She also became very interested in Japanese art and ideas, like ukiyo-e woodblock prints. She introduced Raymond to important people, including the philosopher Rudolf Steiner.

Noémi also designed textiles, rugs, furniture, glass, and silverware. She had exhibitions of her work in Tokyo in 1936 and New York in 1940. Her textiles were even chosen by famous American designers like Louis Kahn for their furniture.

Noémi also helped design Raymond's studio in Nishiazabu. She contributed to several of Raymond's villa designs in the 1950s, including the Hayama Villa (1958).

Raymond's Concrete Legacy

When Raymond started his own office, he focused on using reinforced concrete. He knew about its texture from Cass Gilbert and its strength from Frank Lloyd Wright. He also knew it was good for resisting earthquakes. His first big project in 1921 was the Hoshi Pharmaceutical School. This was one of the first concrete buildings in Tokyo. Raymond used precast concrete for decorations like window frames. He also tried to make wood textures on the concrete, but he later covered it up.

For the Reinanzaka House, skilled workers helped Raymond press the texture of cedar wood onto the concrete. He explored this more on other houses, where the concrete walls had cypress wood textures. At the Karuizawa Studio, workers polished the concrete to show the texture of the stones inside. At Nanzan University, some concrete walls had checkerboard patterns.

Raymond's concrete techniques were very popular in Japan. In 1958, a Japanese architecture magazine editor said that concrete was handled with great care in Japan. He felt that exposed concrete fit Japanese ideas of beauty. Later architects like Tadao Ando became famous for their use of exposed concrete.

Raymond's use of a traditional post and beam structure, but made from concrete, for the Reinanzaka House was a technique adopted by Japanese architects after the war, like Kenzo Tange.

The Golconde dormitory in India used a solid concrete structure with deep overhangs and window covers. This helped the building adapt to the local climate. This building was a pioneer in using reinforced concrete in India.

Antonin Raymond passed away on October 25, 1976, at the age of 88. His wife Noémi died four years later. Raymond Architectural Design Office still operates in Tokyo today.

Selected Works

- Tokyo Woman's Christian College, Tokyo (1921–1938)

- Reinanzaka House, Tokyo (1924)

- Hoshi University Main Building, Tokyo (1924)

- Ehrismann Residence, Yamate, Yokohama (1927)

- Italian Embassy Villa, Nikko (1929)

- Troedsson Villa, Nikko (1931)

- Tokyo Golf Club, Asaka (1932)

- Summer House, Karuizawa (1933)

- Akeboshi Tetsuma House, Tokyo (1933)

- Morinosuke Kawasaki House, Tokyo (1934)

- Tokyo Woman's Christian College Chapel/Auditorium (1934)

- Raymond Farm, New Hope (1939)

- The Huyler Building, Buffalo, New York (interior) (1939–1940)

- St. Joseph the Worker Church, Victorias City, Negros, the Philippines (1949)

- Raymond House and Studio, Azabu (1951)

- Reader's Digest Offices, Tokyo (1951)

- Cunningham House, Tokyo (1954)

- St. Anselm's Church, Tokyo (1954)

- Yawata Steel Otani Gymnasium, KitaKyushu (1955)

- Yaskawa Head Offices, KitaKyushu (1954)

- St. Alban's Church, Tokyo (1956)

- Hayama Villa, Hayama (1958)

- Moji Golf Club, KitaKyushu (1959)

- St. Michael's Church, Sapporo (1960)

- New Studio, Karuizawa (1962)

- St. Paul Church, Shiki (1963)

- St. Paul's Chapel, Rikkyo Niiza Junior and Senior High School, Niiza Campus, Saitama (1963)

- Nanzan University Campus (1964)

- Chapel and Lecture Hall, Rikkyo Boys Primary School, Tokyo (1966)

Awards

- 1952 Architectural Institute of Japan Award for the Reader's Digest Building

- 1956 Medal of Honor by the New York Chapter of American Institute of Architects

- 1957 First Honor Award of the American Institute of Architects and the Yawata Steel Worker's Union Memorial Hall Award of Merit

- 1964 Third Class, Order of the Rising Sun by Emperor Hirohito

- 1965 Design Award from the Architectural Institute of Japan for his design of Nanzan University, Nagoya

See Also

In Spanish: Antonin Raymond para niños

In Spanish: Antonin Raymond para niños

- Czech Republic–Japan relations

- Junzō Yoshimura

Images for kids

| Jewel Prestage |

| Ella Baker |

| Fannie Lou Hamer |