Badger, Shropshire facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Badger |

|

|---|---|

Town Pool, in the village of Badger, Shropshire |

|

| Population | 126 (2011) |

| OS grid reference | SO768995 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority |

|

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Wolverhampton |

| Postcode district | WV6 |

| Dialling code | 01746 |

| Police | West Mercia |

| Fire | Shropshire |

| Ambulance | West Midlands |

| EU Parliament | West Midlands |

| UK Parliament |

|

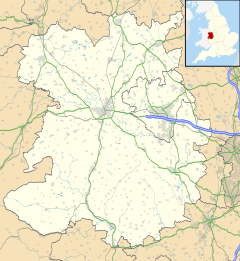

Badger is a small village and civil parish in Shropshire, England. It's about six miles north-east of Bridgnorth. In 2011, about 126 people lived here.

Badger Parish is located at map reference SO 768 995. It includes the village, part of Badger Dingle, and Badger Heath Farm. The parish is about 2.7 kilometers (1.7 miles) wide at its widest point.

The village and its beautiful surroundings, especially the Dingle, are popular places to visit. Their current look is thanks to careful planning and landscaping done in the 1700s.

Contents

What's in a Name? (Etymology)

The name Badger comes from the Old English language, used by the Anglo-Saxons. It has nothing to do with the animal we call a badger today! In fact, in the 1870s, people sometimes spelled it Bagsore.

Experts believe the name has two parts:

- The first part, Bæcg, was an Anglo-Saxon person's name. Maybe it belonged to one of the Angles who settled in the kingdom of Mercia.

- The second part, ofer, means a "hill spur." This is a long, narrow ridge of land that sticks out from a larger hill. At Badger, the village sits to the east of a perfect hill spur. This spur rises behind Badger Farm and slopes down towards the Dingle and the River Worfe.

Badger Through Time (History)

Early Beginnings (Medieval Origins)

Badger likely started in the Anglo-Saxon period. The first clear record is from the Domesday survey in 1086. This survey compared England before and after the Norman Conquest.

The record for Badger says:

- "Osbern, son of Richard, holds BADGER from Earl Roger, and Robert from him.

- Bruning held it; he was a free man.

- 1/2 hide which pays tax. Land for 2 ploughs. In lordship 1 plough; 4 smallholders with 1 plough. Woodland for fattening 30 pigs.

- The value was 7s; now 10s."

This means that before the Normans arrived, an Anglo-Saxon named Bruning owned Badger. It was worth 10 shillings a year. After the Normans, it belonged to Roger de Montgomerie, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury. Osbern fitz Richard, a baron, held it from Earl Roger but let it to someone named Robert.

The population was very small, with only four "smallholders" (farmers with small plots) and their families. A "hide" was a way to measure how much tax land owed. Half a hide was a very small amount. Badger was a tiny village, managed by someone two levels below the powerful Earl Roger.

Later, around the 1100s, the ownership became a bit complex. By the late 1100s, the Prior of Wenlock Priory became the main landlord.

The families who actually lived on and farmed the land, called "terre tenants," had a simpler history. The de Badger family owned it from the mid-1100s until 1402. After that, it was shared by members of the Elmbridge family. In 1560, Dorothy Kynnersley, who was an Elmbridge, passed it to her son, Thomas Kynnersley.

In medieval times, the village was probably surrounded by open fields where everyone farmed together. These fields were later called Batch, Middle, and Uppsfield. Woods were to the west and north, and heathland to the east. The village layout was likely similar to today, with the church, rectory, and hall grouped together, and other houses along the road to the south.

Badger probably got its own church and priest around the mid-1100s. By 1246, the church was known as a rectory. The lord of the manor could choose the priest, but had to pay the Prior of Wenlock a small fee each year. Because Wenlock Priory was connected to an abbey in France, the king often took control of it during the Hundred Years War. This meant the king often chose the priests for Badger.

Badger and nearby Beckbury were part of the Diocese of Hereford until 1905, when they moved to the Diocese of Lichfield. Many early priests were sons of the local lords. The priest earned money from tithes (a portion of crops or income) and Easter offerings, and also had some glebe land (land belonging to the church).

Changes in the Early Modern Period

Under the Kynnersley family, the manor stayed in the same hands for over 200 years. However, there was a disagreement about who could choose the priest. After the dissolution of the monasteries, the king technically had the right to choose. But the Kynnersleys continued to pay to keep their old right.

In 1614, King James I chose Richard Froysall as the new priest without asking Francis Kynnersley, the lord of the manor. Francis fought back! He tried to stop Froysall from entering the church and told villagers not to attend. He even took Froysall's tithes and planted trees on church land. He reportedly threatened to throw Froysall's head in Badger Pool! Francis even got the priest put in prison in Shrewsbury. But Froysall had supporters who stole some of Francis's oxen.

Francis seemed to win his point. The Kynnersley lords slowly became more important locally. Thomas Kynnersley was High Sheriff of Staffordshire and later High Sheriff of Shropshire. His grandson, John, was High Sheriff of Shropshire too. Around 1719, John Kynnersley tore down the old timber-framed manor house and built a new, simpler hall just north of the old spot.

Starting in 1662, farming in Badger changed a lot. A large part of the eastern parish became a separate estate called Badger Heath. Then, a big area of common land (land shared by everyone) was divided up. After this, the old "open field system" was stopped, and the land was enclosed (fenced off into private fields). Heathland was cleared and farmed. By 1748, even the Heath estate was mostly farmland. This farming pattern continues today, with mostly crops but also some pasture for animals.

Badger's population remained small. In the mid-1600s, fewer than 50 adults lived there. Because the village was so small, most priests didn't spend much time there. They often lived elsewhere and had other jobs that paid more. For example, Thomas Hartshorn, who was priest from 1759 to 1780, also held two other church positions near Wolverhampton.

John Kynnersley died without children, so the manor went to his unmarried brother, Clement, who died in 1758. It then passed to his nephew, also named Clement. Both Clements lived near Uttoxeter and didn't live in Badger. They rented the manor house to William Ferriday, an ironmaster. So, for many years, neither the lords of the manor nor the priests lived in the village. The second Clement decided to sell Badger in 1774.

Building the Modern Village

The buyer was Isaac Hawkins Browne, a wealthy industrialist and politician from Derbyshire. After traveling around Europe, Browne decided to live as a country gentleman on his estates in Badger and Malinslee. He helped publish his father's poetry. Browne became well-liked by the local wealthy families. He served as High Sheriff in 1783 and was a member of parliament for Bridgnorth from 1784 to 1812.

Browne spent a lot of money on Badger Hall. Between 1779 and 1783, he made it much bigger, with a museum, library, and conservatory. It had fancy plasterwork and paintings. Then, Browne focused on the landscape.

His work on the landscape made the biggest and most lasting change to Badger. He improved the valley along the Batch Brook, on the south side of the village. This reshaped area, called Badger Dingle, became a famous example of the "picturesque" style of landscaping. It had two miles of walking paths, waterfalls created by damming the brook, a "temple," and other special features. The pools in the village itself, which flow into the Dingle, were also made larger and reshaped at this time.

Browne was a kind landlord and employer. He gave coal to villagers and helped the poor. He likely started and paid for the main village school, which provided primary education until 1933.

Browne also wanted the parish to have better spiritual care. For at least 100 years, none of the priests had actually lived in Badger, and church services were rare. This bothered Browne. He even spoke in parliament about making absent clergy pay for replacement priests. Dr. James Chelsum was the priest from 1780. He also held other church jobs and didn't live in Badger. Browne eventually arranged for Chelsum to leave in 1795. In his place, Browne chose William Smith, who was a dedicated priest for 42 years. Smith was almost never absent from the parish. Browne valued Smith so much that he left him the right to choose his own successor. Smith later sold this right back to Browne's widow in 1820.

Browne's first wife, Henrietta Hay, died in 1802. The next year, he married Elizabeth Boddington. When Browne died in 1818, he left the hall to his wife for her lifetime. She lived for another 21 years and continued Browne's good deeds, making sure the school stayed open. She also paid most of the cost to rebuild the parish church, dedicated to St. Giles.

In 1833, work began on rebuilding the church. The old materials were used where possible, and more sandstone was quarried from the estate. Five years later, a new rectory (the priest's house) was built. When William Smith died in 1837, Elizabeth chose a relative, Thomas F. Boddington, as the new priest. He lived in Shifnal for at least part of his time.

- The parish church of St. Giles

Changes and Growth (Decline and Recovery)

After Browne's wife died in 1839, the estate went to his nephew, Robert Henry Cheney. Cheney was an artist who specialized in buildings and landscapes. He also became a pioneer photographer. He opened the Dingle to visitors for the first time, and people from industrial towns started coming to walk there. He died without children in 1866 and left the estate to his brother Edward.

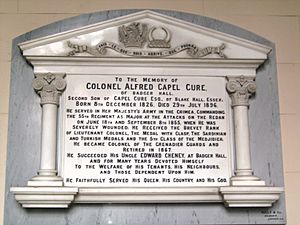

When Edward died in 1884, Badger went to their nephew, Alfred Capel Cure. He was a hero from the Crimean War and was wounded in 1855. He learned photography from his uncle and became a skilled photographer, especially of buildings. His photos are so important that they've been shown in museums like MoMA in New York! He added a private family chapel to the north side of the church. After owning Badger for 12 years, he died in an accident while trying to blow up tree stumps on another estate. The Capel Cure family owned the estate until after World War II.

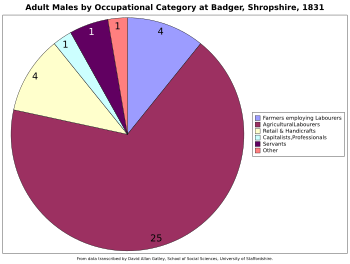

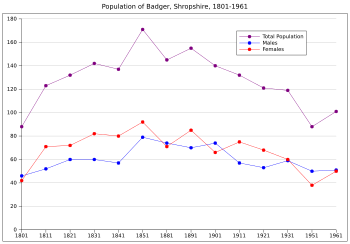

Badger's population grew in the first half of the 1800s. It went from 88 people in 1801 to 142 in 1831. In 1831, a census showed what men did for work. Out of 37 adult men, 25 (more than two-thirds) were farm laborers, and four were farmers. Most people in the village depended on agriculture.

The population kept rising to a peak of 178 in 1861. After that, like many farming villages, it started to shrink. By 1951, it was back down to 88 people, the same as in 1801. This happened because farming needed fewer workers. Farm sizes grew, new crops and methods were used, and machines took over jobs.

As the population declined, some village institutions struggled. The school closed in 1933 after the teacher, Emma Grainger, and the school's supporter, Francis Capel Cure, both died. After that, children went to schools in Beckbury or Worfield.

In 1952, the long-serving priest, Rev. Archibald Dix, retired. The parish was then combined with Beckbury. Later, it became part of a group of six parishes. Archibald Dix's daughter, Margaret Dix, a famous surgeon, bought the rectory and lived there until she died in 1992. She was known for her work in brain and ear medicine. She left the house for Christian purposes. It was used as a holiday home by a charity until it was sold as a private home in 2005.

Around the same time, the old, decaying Hall and estate were sold to John Swire and Sons, a huge company that deals with property, finance, shipping, and airlines. Sir Adrian Swire is now the lord of the manor. Most of the Hall was torn down in 1953. A smaller building and gatehouse were renamed Badger Hall and still stand today. They are grand enough to make visitors think the original Hall is still there.

However, the 1950s marked a turning point. With more cars available, villages like Badger became more attractive places to live. New houses were built, and the village has almost doubled in size since World War II. This means Badger has changed from a working village to mostly a residential community. Despite these changes, the village still looks old and picturesque, which continues to attract visitors.

Badger's Landscape (Geography)

Where is Badger? (Location and Boundaries)

The village of Badger is located where the River Worfe (also called the Cosford Brook) meets one of its smaller streams, known as the Batch, Heath, or Snowdon Brook. The Snowdon Brook roughly forms the eastern and southern borders of the parish. The western boundary is close to the River Worfe. These streams were likely the exact boundaries before their courses changed slightly over time. Both the Worfe and the Snowdon flow into the much larger River Severn. The Worfe flows south and west to join the Severn just above Bridgnorth.

The village is about 65 meters (213 feet) above sea level. However, the hill spur to the west, which probably gave the village its name, rises to about 95 meters (312 feet). The parish is about 2.5 kilometers (1.5 miles) from east to west and 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) from north to south, covering an area of 374 hectares (924 acres).

What's Under the Ground? (Geology)

The village and the area to its north sit on Upper Mottled Sandstone. This type of rock was formed during the Triassic period and is found in many parts of the West Midlands. This sandstone has been widely used for building in the village, including St. Giles church. You can see it clearly in the Dingle, along the Snowdon Brook, where there are rock outcrops, cliffs, and caves. These were cleverly shown off and improved during the 1700s landscaping of the valley. The eastern side of the parish has boulder clay, sand, gravel, or "till," which are deposits left behind by glaciers during the ice ages.

How People Get Around (Communications)

Badger has always depended on roads. Historically, the most important road ran south from Beckbury and then sharply east to Pattingham. This road has been changed so that traffic now mainly turns south towards Stableford. There, a smaller road connects to a B-road that links Telford with the Black Country. Old maps show that until Victorian times, a road also crossed the Dingle directly to Ackleton, but this has now become just a footpath.

Things to See (Features)

Here are some interesting or attractive places to see around Badger today:

The Village Pools

There are four pools in the village, but two are very noticeable: the Church Pool and the Town Pool. These pools were created by damming a small stream that flows down to the Snowdon Brook in the Dingle. They got their current look in the late 1700s, thanks to the landscaping ordered by Isaac Hawkins Browne. However, they had been a main feature of the village for centuries before, as shown by Francis Kynnersley's threat in 1614 to throw the priest into the pond! 52°35′37″N 2°20′39″W / 52.5935°N 2.3441°W

St. Giles' Parish Church

The parish church is a small but beautiful example of Gothic Revival architecture. It was rebuilt starting in 1833, using the original site and materials as much as possible. Inside, you can find remarkable funeral art, including pieces by famous sculptors like Francis Leggatt Chantrey, John Flaxman, and John Gibson. Location: 52°35′38″N 2°20′37″W / 52.5938°N 2.3437°W.

- Funerary art in St. Giles church

Badger Dingle

Badger Dingle is a special place listed as Grade II in Historic England's Register of Parks and Gardens. It's a great example of picturesque landscape architecture. This narrow valley south of the village was opened to the public in 1851. While it has had periods of neglect, it's now quite easy to visit. Paths are good in dry weather, and a new bridge over the Upper Pool makes it possible to do circular walks. The best entrances are across from the village cemetery. Badger Dingle is thought to be the inspiration for "Badgwick Dingle" in the Blandings novels by P.G. Wodehouse, whose family lived nearby when he was young. Location: 52°35′32″N 2°20′45″W / 52.5921°N 2.3457°W.

- Badger Dingle

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |