Domesday Book facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Domesday Book |

|

|---|---|

| The National Archives, Kew, London | |

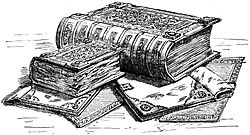

Domesday Book: an engraving published in 1900. Great Domesday (the larger volume) and Little Domesday (the smaller volume), in their 1869 bindings, lie on their older "Tudor" bindings.

|

|

| Also known as | Great Survey Liber de Wintonia |

| Date | 1086 |

| Place of origin | England |

| Language(s) | Medieval Latin |

The Domesday Book is a very old record book from England. It was finished in 1086. King William I, also known as William the Conqueror, ordered it to be made. He wanted to know everything about his new kingdom.

The book was originally called Liber de Wintonia. This means "Book of Winchester". It was kept in the royal treasury there. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says that in 1085, the king sent people all over England. Their job was to list everything the king owned. They also recorded what money or goods were owed to him.

The Domesday Book was written in Medieval Latin. It used many short forms of words. It also included some English words that had no Latin translation. The main goal was to record the yearly value of every piece of land. It also listed the land, people, and animals that made up this value.

The name "Domesday Book" started being used in the 12th century. Richard FitzNeal wrote in 1179 that its decisions were final. No one could change them, like the decisions of the Last Judgement.

Today, the Domesday Book is kept at The National Archives in Kew, London. It was first fully printed in 1783. In 2011, it became available to view online.

This book is a very important source for historians. It helps them understand what England was like long ago. No other survey like it was done in Britain until 1873. That later survey was sometimes called the "Modern Domesday."

Contents

What's Inside the Domesday Book?

The Domesday Book is made of two main parts. They were originally two separate books. "Little Domesday" covers Norfolk, Suffolk, and Essex. "Great Domesday" covers most of the rest of England. It also includes parts of Wales near English counties. Some northern areas were not included. These were places like Westmorland and Northumberland. They did not pay the national land tax, which was called the geld.

"Little Domesday" is smaller in size but has more details. For example, it lists the number of farm animals owned by lords. Great Domesday is shorter and more organized.

How the Book is Organized

Both books are divided into sections. Each section lists the lands held by a "tenant-in-chief". These were people who held land directly from the king. They included bishops, abbots, and powerful lords from Normandy. Some English lords were also included.

The richest lords owned hundreds of manors. A manor was a large estate. These manors were often spread across England. For example, Baldwin the Sheriff had 176 manors in Devon. He also had four nearby in Somerset and Dorset.

The king was the ultimate owner of all land in England. Everyone else "held" land from him. This was part of the feudal system. The king's own lands were listed first in each county. Then came the lands of bishops, abbeys, and other religious groups. After that, the lands of lay (non-religious) lords were listed.

Some towns had their own special sections. A few sections listed land disputes. These were called clamores (claims).

People, Places, and Resources

The Domesday Book counts 268,984 heads of households. This means about 1.2 to 1.6 million people lived in England then. Some people, like those in cities, were not counted.

The book names 13,418 places. It has interesting details about many towns. These details often relate to the king's rights. For example, it mentions markets and places where coins were made. It also records old payments to the king, like honey.

The Domesday Book lists 5,624 mills. These were watermills used for grinding grain. This number is likely low, as the book is not complete. A century earlier, fewer than 100 mills were recorded. This shows a big increase in bread eating. The book also lists 28,000 slaves. This was a smaller number than in 1066.

The scribes who wrote the Domesday Book used spelling that was influenced by French.

Why Was the Survey Made?

There were several reasons why King William ordered this huge survey.

Finding Out About Taxes

The main reason was to understand the king's financial rights. This included the national land-tax called geldum. It also covered other payments and income from royal lands.

After the Norman Conquest, many English lands changed hands. William wanted to make sure he still received all the money owed to the Crown. He also wanted to know the value of his new kingdom. This helped him compare it to older tax records.

Understanding the Kingdom's Wealth

The survey recorded the annual value of all land. It listed the value at different times. These times were:

- When Edward the Confessor died (before William became king).

- When the new owners received the land.

- When the survey was done.

It also estimated the future value. William wanted to know how rich his kingdom was. The Domesday Book mostly focuses on rural estates. These were the main source of wealth back then.

The book lists the amount of arable land (land for farming). It also records the number of plough teams. Each team had eight oxen. It describes meadows, woodlands, and pastures. It also mentions fisheries, water-mills, and salt-pans. The different types of peasants are listed. Finally, it estimates the yearly value of everything.

Controlling His Lords

The survey also helped William understand his new lords. It showed how much land each baron owned. It also showed who their "under-tenants" were. These were people who held land from the barons.

This information was important for William. It helped him for military reasons. It also helped him make sure everyone was loyal to him. He wanted under-tenants to swear loyalty directly to him.

The survey gave the king information about where to get money. It listed income sources. It did not list expenses, like castles. But it might mention castles if they caused changes in land ownership. For example, if houses were knocked down to build a castle.

How the Survey Was Done

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says the planning for the survey began in 1085. The book itself says the survey was finished in 1086. It is believed that one person copied out Great Domesday. Six scribes worked on Little Domesday.

Royal officers visited most counties. They held public meetings called shire courts. Representatives from every town attended these meetings. Local lords were also there.

The survey focused on areas called "Hundreds." These were smaller divisions within each county. Twelve local jurors swore to the truth of the information. Half of these jurors were English, and half were Norman.

Some original records from these surveys still exist. For example, the "Cambridge Inquisition" for Cambridgeshire. The Exon Domesday covers Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset, and part of Wiltshire. These records show the full details collected by the survey.

Historians have figured out that the survey was done in six main "circuits" or areas. Little Domesday was a seventh circuit.

- Berkshire, Hampshire, Kent, Surrey, Sussex

- Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset, Wiltshire

- Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Cambridgeshire, Hertfordshire, Middlesex

- Leicestershire, Northamptonshire, Oxfordshire, Staffordshire, Warwickshire

- Cheshire, land between Ribble and Mersey (now Lancashire), Gloucestershire, Herefordshire, Shropshire, Worcestershire

- Derbyshire, Huntingdonshire, Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, Rutland, Yorkshire

The Name "Domesday"

The original books did not have a formal title. People called it a "description" or the king's "writings." Around 1100, it was called the "book" or "charter" of Winchester. This was because it was kept there.

The English people greatly respected the book. They started calling it "Domesday Book." This name refers to the Last Judgment. It meant that the book's records were final and could not be changed. The old English word "doom" meant a law or judgment. It did not mean disaster back then.

The name "Domesday" was officially used in 1221.

Some people later thought the name came from the Latin phrase Domus Dei. This means "House of God." They thought it referred to the church in Winchester where the book was kept. This led to the spelling "Domesdei" for a while.

Today, scholars usually call it "Domesday Book" or just "Domesday."

Where the Book Has Been Kept

From the late 11th century to the early 13th century, the Domesday Book was kept in the royal treasury at Winchester. This was the capital city of the Norman kings.

Later, the treasury moved to the Palace of Westminster in London. The Domesday Book moved with it. It stayed in Westminster for centuries. Sometimes it was moved for safety. For example, it went to Nonsuch Palace after the Great Fire of London in 1666.

From the 1740s, it was kept in the chapter house of Westminster Abbey. In 1859, it moved to the new Public Record Office in London. Today, it is at The National Archives in Kew. The old chest where it was stored is also there.

The books have rarely left the London area in modern times. They were sent to Southampton for copying in 1861–63. During the First World War and Second World War, they were moved to prisons for safety.

How the Book Was Bound

The Domesday Book has been rebound many times. This means new covers were put on it. Little Domesday was rebound in 1320. Both books got new covers in the Tudor period. They were rebound twice in the 19th century. In 1952, they were rebound again. For the 900th anniversary in 1986, they were rebound once more. Great Domesday was split into two books then. Little Domesday was split into three.

How the Book Was Published

The government started printing the Domesday Book in 1773. It came out in two volumes in 1783. It was printed in a special font to look like the original writing. Later, indexes and extra volumes were added. These included other old surveys.

In 1861–1863, photographic copies were made for each county. Today, you can find many versions of the Domesday Book. They are often separated by county.

In 1986, the BBC created the BBC Domesday Project. This was a new survey to mark the 900th anniversary. In 2006, the Domesday Book was put online. You can look up place names and see the original entries. You can also download pages.

Still Used in Law Today

Even today, the Domesday Book is sometimes used in law courts. It can help prove old property rights. For example, it was used in 1960 to show legal use rights on a foreshore. In 2010, it helped prove a manor's sporting rights. In 2019, it was used to support a market's rights.

Why the Domesday Book is Important

The Domesday Book is very important for understanding the past. Clifford Darby said it is the oldest "public record" in England. He called it "the most remarkable statistical document in the history of Europe." No other country has such a detailed description of its land from that time.

Historians can learn so much from it. They can see details about people, farms, woodlands, and other resources. It gives the earliest survey of each town or manor. It also helps trace how land ownership changed over time.

However, the book is not perfect. The clerks who wrote it sometimes made mistakes. They forgot things or got confused. Using Roman numerals also led to errors. There are also some missing parts and unclear descriptions. So, while it's an amazing record, it's important to remember these challenges when studying it.

See also

In Spanish: Libro Domesday para niños

In Spanish: Libro Domesday para niños