Bongo (antelope) facts for kids

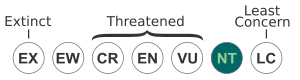

The Bongo (scientific name: Tragelaphus eurycerus) is a large antelope that mostly comes out at night (this is called nocturnal). There are two main types, or subspecies: the western (or lowland) bongo and the eastern (or mountain) bongo. The western bongo is currently 'near threatened,' meaning its numbers are getting low. The eastern bongo is 'critically endangered,' which means it's in serious danger of disappearing forever.

Bongos are herbivores, so they only eat plants. They live in the thick forests of Africa. You can only find eastern bongos living wild in Kenya. Just like the west African giraffe, the eastern (or mountain) bongo is one of Africa's most endangered animals. Bongos live both in the wild and in special animal parks or zoos. Both male and female bongos grow horns as they get older.

Quick facts for kids Western/Lowland Bongo |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Subphylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Genus: |

Tragelaphus

|

| Species: |

T. eurycerus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Tragelaphus eurycerus Ogilby, 1837

|

|

Contents

Where Bongos Live and Their Homes

Bongos live in warm, wet jungles in Central Africa. They like places with lots of thick plants and can be found up to 4,000 meters (13,000 feet) high in mountains. You can find them in countries like Kenya, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. They also live in the Ivory Coast, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and South Sudan.

Long ago, bongos lived in three separate parts of Africa: East, Central, and West. Today, the areas where they live have become much smaller. This is because people are cutting down forests for farms and wood. People also hunt bongos for their meat.

Bongos prefer forests that have been disturbed, like by elephants eating plants, fires, or floods. These changes create new, low-growing plants for them to eat. They can even live in forests made of bamboo.

What Bongos Look Like

Bongos are some of the biggest antelopes that live in forests. They have a deep reddish-brown coat with bright white stripes on their sides. These stripes help them blend in with the trees and shadows, which is called camouflage.

Both male and female bongos are similar in size. An adult bongo stands about 1.1 to 1.3 m (3.6 to 4.3 ft) tall at the shoulder. They are about 2.15 to 3.15 m (7.1 to 10.3 ft) long, including their tail, which is about 45–65 cm (18–26 in). Female bongos weigh around 150–235 kg (331–518 lb), while males are heavier, weighing about 220–405 kg (485–893 lb).

Both male and female bongos have heavy, spiral horns. The male's horns are usually longer and thicker. All bongos living in zoos today came from a small group in the Aberdare Mountains of central Kenya.

Their Coat and Body

Bongos have a shiny reddish-brown or chestnut coat. Their neck, chest, and legs are usually darker than the rest of their body. As male bongos get older, their coats become even darker, turning a deep mahogany-brown. Female bongos usually have brighter colored coats than males. Eastern bongos are generally darker than western bongos, especially older males.

The color from their coat can rub off easily. Some people have even said that rain running off a bongo can look reddish! Their smooth coat has 10 to 15 white-yellow stripes running down their sides, from their neck to their back. The number of stripes is rarely the same on both sides. They also have a short, stiff, brown ridge of hair along their back, and the white stripes go into this ridge.

Bongos have a white V-shape between their eyes and two big white spots on each cheek. Another white V-shape is found where their neck meets their chest. Their large ears help them hear very well. Their unique colors might help bongos recognize each other in the dark forest. Bongos don't have special scent glands, so they don't rely on smell as much as other antelopes to find each other. A bongo's lips are white, and its nose is black.

Their Horns

Bongos have two heavy, slightly spiraled horns that curve back over their shoulders. Both male and female bongos have horns, which is special because most other antelopes only have horns on the males. Bongo horns look like a lyre (a type of harp) and are similar to the horns of other antelopes like nyalas and kudus.

Unlike deer, which grow new antlers every year and then shed them, bongos and other antelopes keep their horns for their whole lives. Male bongos have very large, swept-back horns, while females have smaller, thinner horns that are more straight. The horns can be between 75 and 99 cm (29.5 and 39 in) long and twist once.

Like all antelope horns, the inside of a bongo's horn is hollow. The outside layer is made of keratin, which is the same material as human fingernails and hair. Bongos can run very fast and gracefully through thick plants, laying their heavy horns back on their shoulders so the branches don't get in the way. Sadly, people sometimes hunt bongos for their horns.

How Bongos Live Together and Behave

Bongos are not often seen in large groups. Male bongos, called bulls, usually live alone. Female bongos with their young live in small groups of six to eight. It's rare to see a herd of more than 20 bongos. A female bongo is pregnant for about 285 days (about 9.5 months) and usually has one baby at a time. The baby drinks milk from its mother for about six months. Bongos become adults and can have their own babies when they are about 24–27 months old.

Because their forest home is so thick and hard to move through, not many people from Europe or America saw bongos until the 1960s. When young male bongos grow up and leave their mothers' groups, they usually live alone. Sometimes, they might join an older male. Adult males of similar size tend to avoid each other. If they do meet, they might have a gentle "sparring" match with their horns, but serious fights are rare. Instead, they try to scare each other away by puffing out their necks, rolling their eyes, and holding their horns straight up while walking slowly back and forth.

Males only look for females when it's time to mate. When a male is with a group of females, he doesn't try to control them or stop them from moving, unlike some other antelopes.

Bongos are mostly active at night (nocturnal), but sometimes they are active during the day. They are shy and easily scared. If a bongo gets scared, it runs away very fast, even through thick bushes. Once they find a hiding spot, they stay alert and face away from whatever scared them, peeking back now and then to check. A bongo's back end is harder to see than its front, which helps it escape quickly from this position.

When a bongo is in trouble, it makes a sound like a bleat. They don't make many different sounds, mostly grunts and snorts. Female bongos make a soft "mooing" sound to call their babies. Female bongos like to have their babies in certain safe areas. Newborn calves hide for a week or more, and their mothers visit them briefly to feed them milk.

The baby bongos grow quickly and can soon join their mothers in the groups. Their horns grow fast and start to show in about 3.5 months. They stop drinking milk after six months and can have their own babies when they are about 20 months old.

What Bongos Eat

Like many forest animals with hooves, bongos are herbivores that eat plants. They munch on leaves from trees and bushes, vines, bark from rotting trees, grasses, roots, and fruits.

Bongos need salt in their food, so they often visit natural salt licks. Scientists have found charcoal from burnt trees in bongo droppings. It's thought that they eat this charcoal to get salts and minerals. This behavior is also seen in the okapi, another forest animal. Like the okapi, bongos have a long, flexible tongue that they use to grab grasses and leaves.

Bongos need to live in places where there is always water available. Since they are large animals, they need a lot of food. This means they can only live in areas where there are plenty of herbs and low bushes growing all year round.

Bongo Numbers and How We Protect Them

It's hard to count exactly how many bongos there are. Experts guess there are around 28,000 bongos in total. Only about 60% of them live in protected areas. This means the actual number of lowland bongos might only be in the low tens of thousands. In Kenya, their numbers have dropped a lot. On Mt. Kenya, they disappeared completely in the last ten years because of illegal hunting with dogs. Even though we don't have all the information, lowland bongos are not currently considered endangered.

Bongos can get sick from diseases like rinderpest, which almost wiped them out in the 1890s. They can also suffer from a condition called goitre, where their thyroid glands get very big. This might happen because of their genes and things in their environment.

Leopards and spotted hyenas are the main natural hunters of bongos. Pythons sometimes eat baby bongos. Humans also hunt bongos for their fur, horns, and meat. Bongo populations have been greatly reduced by hunting and poaching, but there are some safe places for bongos to live.

Many people who lived near bongos used to believe that if they ate or touched a bongo, they would have shaking fits, like epileptic seizures. Because of this old belief, bongos were not harmed as much as expected in their native homes. However, these old beliefs are said to be gone now, which might be why more bongos are being hunted by people today.

Zoo Programs to Help Bongos

Zoos around the world keep a special record book to help manage bongos in captivity. Because of their bright colors, bongos are very popular in zoos and private collections. In North America, there are thought to be over 400 bongos in zoos. This number is probably even higher than the number of mountain bongos living in the wild!

In 2000, the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) started a special plan for bongos called a Species Survival Plan. This plan helps make sure that bongos in zoos have healthy babies and keep their genetic diversity. The goal for zoos in North America is to have 250 bongos. Thanks to the hard work of these zoos, there are plans to reintroduce bongos born in zoos back into the wild in Kenya.

One project has already sent bongos from North American zoos back to Africa. In 2004, 18 eastern bongos born in zoos in North America were brought together at White Oak Conservation in Yulee, Florida. From there, they traveled with staff members to a special holding area on Mt. Kenya. They stayed there until they were ready to be released into the wild.

Images for kids

-

A skeleton of the bongo exhibited at the Museum of Veterinary Anatomy FMVZ USP, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science, University of São Paulo

-

A baby eastern bongo at Louisville Zoo in Kentucky

See also

In Spanish: Tragelaphus eurycerus para niños

In Spanish: Tragelaphus eurycerus para niños

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |