Demagogue facts for kids

A demagogue (pronounced DEM-uh-gog) is a political leader in a democracy who becomes popular by getting ordinary people excited against the elites (people with power or wealth). They often do this by using strong speeches that stir up emotions. They might blame certain groups for problems, make dangers seem worse than they are, or even lie to get people to feel a certain way.

Demagogues often ignore or break the usual rules of how politics should work. They might promise to change everything or even threaten to do so.

Historian Reinhard Luthin described a demagogue as a politician who is good at speaking, flattering, and insulting others. They avoid talking about important issues and promise everything to everyone. They appeal to people's feelings rather than their logic, and they stir up prejudices based on race, religion, or social class. A demagogue wants power more than anything and will do whatever it takes to control the masses. This type of leader has existed for centuries, almost as long as Western civilization itself.

Demagogues have appeared in democracies since ancient Athens. They take advantage of a weakness in democracy: since the people hold the final power, it's possible for them to give that power to someone who appeals to the simplest desires of a large group. Demagogues usually push for quick, strong action to solve a crisis. They often accuse their calm and thoughtful opponents of being weak or disloyal. Many demagogues who have been elected to high office have tried to remove the limits on their power and turn their democracy into a dictatorship, sometimes succeeding.

Contents

What the word "demagogue" means

A demagogue, in the strict signification of the word, is a 'leader of the rabble'.

—James Fenimore Cooper, "On Demagogues" (1838)

The word demagogue first came from ancient Greece. It originally meant a leader of the common people and didn't have a bad meaning. However, it later came to describe a troublesome kind of leader who sometimes appeared in Athenian democracy. Even though democracy gave power to ordinary people, elections often still favored the wealthy class, who preferred careful discussion and good manners.

Demagogues were a new kind of leader who came from the lower classes. They constantly pushed for action, often violent, right away and without much thought. Demagogues directly appealed to the feelings of the poor and less educated. They sought power, told lies to create panic, used crises to gain more support for their calls for immediate action and more authority, and accused moderate opponents of being weak or disloyal to the nation.

The word demagogue has been used to criticize leaders who are seen as manipulative, harmful, or prejudiced. It's hard to draw a clear line between demagogues and non-demagogues, as democratic leaders exist on a scale. What makes someone a demagogue is how they gain or keep power: by exciting the strong feelings of the lower classes and less-educated people in a democracy, leading them toward quick or violent actions, and breaking established democratic rules like the rule of law.

In 1838, James Fenimore Cooper identified four main traits of demagogues:

- They act like they are just ordinary people, against the powerful elites.

- Their politics relies on a very strong emotional connection with the people, much more than normal popularity.

- They use this connection and the huge popularity it brings for their own benefit and goals.

- They threaten or openly break established rules, institutions, and even laws.

The main feature of a demagogue's style is persuading people through strong emotions. This stops people from thinking carefully and considering other options. While many politicians might sometimes bend the truth a little to stay popular, demagogues do this all the time, without holding back. Demagogues "play on strong feelings, prejudices, narrow-mindedness, and lack of knowledge, rather than on reason."

Why demagogues keep appearing

In every age the vilest specimens of human nature are to be found among demagogues.

—Thomas Macaulay, The History of England from the Accession of James II (1849)

Demagogues have appeared in democracies from ancient Athens to today. Even though most demagogues have their own unique personalities, their ways of influencing people have stayed the same throughout history.

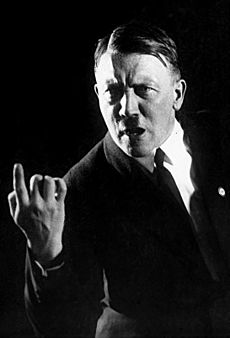

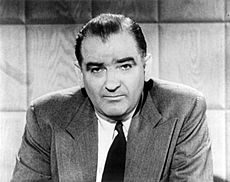

Often called the first demagogue, Cleon of Athens is remembered for his harsh rule and how he almost destroyed Athenian democracy. He did this by appealing to the "common-man" and ignoring the calm traditions of the wealthy elite. More recent demagogues include Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, Huey Long, and Joseph McCarthy. All of them gained many followers in the same way Cleon did: by exciting the strong feelings of the crowd against the calm, thoughtful traditions of the powerful people of their time. All of them, ancient and modern, fit Cooper's four traits: they claimed to represent ordinary people, stirred up strong emotions, used those reactions to gain power, and broke or threatened established political rules, though each in different ways.

Demagogues take advantage of a constant weakness in democracies: the larger number of votes from the lower classes and less-educated people. These are the people most likely to be whipped into a frenzy and led to bad actions by a speaker who is good at stirring up such feelings. Democracies are made to protect freedom for everyone and give people control over the government. Demagogues turn the power they get from popular support into a force that harms the very freedoms and rule of law that democracies are meant to protect. The Greek historian Polybius believed that democracies are always ruined by demagogues. He said that every democracy eventually turns into "a government of violence and the strong hand," leading to "noisy meetings, killings, and banishments."

While many people think of democracy and fascism as complete opposites, ancient political thinkers believed that democracy naturally tended to lead to extreme populist governments. They thought it gave dishonest demagogues the perfect chance to seize power.

How demagogues work

Below are some ways demagogues have influenced and excited crowds throughout history. Not all demagogues use all these methods, and no two use the exact same ones to become popular. Even regular politicians use some of these techniques sometimes; a politician who couldn't stir any emotions would likely not get elected. What these techniques have in common, and what makes a demagogue's use of them different, is that they are used constantly to stop careful thinking by creating overwhelming strong feelings.

Sometimes, a true statesman (a politician genuinely focused on good policies) might need to use some demagogic tactics to stop a real demagogue – to "fight fire with fire." A real demagogue uses these tactics without limits. A statesman, however, only uses them to prevent greater harm to the nation. Unlike a demagogue, a statesman's usual way of speaking tries "to calm rather than excite, to bring people together rather than divide, and to teach rather than flatter."

Blaming others

The most basic demagogic technique is scapegoating: blaming a group's problems on another group. This other group is usually different in ethnicity, religion, or social class. For example, Joseph McCarthy claimed that all of the problems in the U.S. came from "communist spies." Denis Kearney blamed all the problems of workers in California on Chinese immigrants. Hitler blamed Jews for Germany's defeat in World War I and the economic problems that followed. This was a key part of his appeal: many people said they liked Hitler only because he was against the Jews. Blaming the Jews gave Hitler a way to increase nationalism and unity.

The claims made about the blamed group are often similar, no matter who the demagogue is or which group is being blamed. The message is often: "We" are the "true" people (Americans, Germans, Christians, etc.), and "they" (Jews, bankers, communists, foreigners, elites, etc.) have cheated "us" ordinary folk and are living in luxury off wealth that should be "ours." "They" are plotting to take over, are quickly gaining power, or are already secretly running the country. "They" are less than human, and if "we" don't get rid of them right away, disaster is coming.

Creating fear

Many demagogues have gained power by making their audiences afraid. This fear is used to push people to act and stop them from thinking things through.

Lying

While any politician needs to point out dangers and criticize opponents' policies, demagogues choose their words for emotional impact on the audience. They usually don't care about the facts or how serious the danger really is. Some demagogues are opportunists, watching the people and saying whatever will create the most excitement at that moment. Other demagogues might be so uninformed or prejudiced themselves that they truly believe the lies they tell.

When one lie doesn't work, the demagogue quickly moves on to more lies. Joe McCarthy first claimed to have "here in my hand" a list of 205 members of the Communist Party working in the State Department. Soon this number changed to 57 "card-carrying Communists." When asked for names, McCarthy then said that while the records weren't available to him, he knew "absolutely" that "about" 300 Communists were supposed to be fired, but only "about" 80 actually were. When challenged on that, he said he had a list of 81, which he would use in the following weeks. McCarthy never found even one Communist in the State Department.

Emotional speeches and personal charm

Many demagogues have shown amazing skill at moving audiences to deep emotional levels during a speech. Sometimes this is because they are excellent speakers, sometimes because they have great personal charm, and sometimes both. Hitler showed both. His eyes seemed to have a hypnotic effect on many people, making them feel stuck and overwhelmed. Hitler usually started his speeches slowly, in a deep, powerful voice. He would talk about his life in poverty after World War I, suffering in the chaos and shame of post-war Germany, and his decision to awaken Germany again. Gradually, he would raise the tone and speed of his speech, ending in a peak where he screamed his hatred of Bolsheviks, Jews, Czechs, Poles, or whatever group he felt was in his way. He would mock them, make fun of them, insult them, and threaten them with destruction. Normally reasonable people got caught up in the strange connection Hitler made with his audience, believing even the most obvious lies and nonsense while under his spell. Hitler was not born with these speaking skills; he learned them through long and careful practice.

A more typical smooth-talking demagogue was James Kimble Vardaman (Governor of Mississippi 1904–1908, Senator 1913–1919). Even his opponents admired his speaking gifts and colorful language. For example, when responding to Theodore Roosevelt inviting black people to a reception at the White House, Vardaman said: "Let Teddy take coons to the White House. I should not care if the walls of the ancient edifice should become so saturated with the effluvia from the rancid carcasses that a Chinch bug would have to crawl upon the dome to avoid asphyxiation." Vardaman's speeches often had little real content. He spoke in a formal style even in serious meetings. His speeches mostly served as a way to show off his personal charm, pleasant voice, and graceful delivery.

The charisma and emotional speeches of demagogues often helped them win elections even when the press was against them. The news media gives voters information, and this information is often damaging to demagogues. Demagogic speeches distract, entertain, and captivate, turning followers' attention away from the demagogue's usual history of lies, abuses of power, and broken promises. The invention of radio allowed many 20th-century demagogues' skill with spoken words to overpower the written words of newspapers.

Accusing opponents of weakness and disloyalty

Cleon of Athens, like many demagogues after him, constantly pushed for harshness to show strength. He argued that showing compassion was a sign of weakness that enemies would just use against them. He said, "It is a general rule of human nature that people despise those who treat them well and look up to those who make no concessions." During the Mytilenian Debate about whether to take back the order he had given the day before to kill and enslave everyone in Mytilene, he was against the idea of debate itself. He called it a lazy, weak, intellectual pleasure: "To feel pity, to be carried away by the pleasure of hearing a clever argument, to listen to the claims of decency are three things that are entirely against the interests of an imperial power."

To distract from his lack of proof for his claims, Joe McCarthy kept suggesting that anyone who opposed him was a communist supporter. G.M. Gilbert summed up this way of speaking as "I'm against Communism; you're against me; therefore you must be a communist."

Promising the impossible

Another basic demagogic technique is making promises just for their emotional effect on audiences. They don't care how these promises might be achieved or if they even plan to keep them once in office. Demagogues state these empty promises simply and dramatically, but they are very unclear about how they will achieve them, because usually they are impossible. For example, Huey Long promised that if he were elected president, every family would have a home, a car, a radio, and $2,000 yearly. He was vague about how he would make that happen, but people still joined his Share-the-Wealth clubs. Another type of empty demagogic promise is to make everyone rich or "solve all the problems." The Polish demagogue Stanisław Tymiński, running as an unknown "outsider" based on his past success as a businessman in Canada, promised "immediate prosperity." He took advantage of the economic problems of workers, especially miners and steelworkers. Tymiński forced a second round of voting in the 1990 presidential election, almost defeating Lech Wałęsa.

Personal insults and ridicule

Many demagogues have found that making fun of or insulting opponents is a simple way to stop careful discussion of different ideas, especially with an audience that isn't very educated. "Pitchfork Ben" Tillman, for example, was very good at personal insults. He got his nickname from a speech where he called President Grover Cleveland "an old bag of beef" and said he would bring a pitchfork to Washington to "poke him in his old fat ribs." James Kimble Vardaman often called President Theodore Roosevelt a "coon-flavored miscegenationist" and once put an ad in a newspaper for "sixteen big, fat, mellow, rancid coons" to sleep with Roosevelt during a trip to Mississippi.

A common demagogic technique is to give an opponent an insulting epithet (a descriptive nickname). They do this by saying it repeatedly, in speech after speech, when saying the opponent's name or instead of it. For example, James Curley called Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., his Republican opponent for Senator, "Little Boy Blue." William Hale Thompson called Anton Cermak, his opponent for mayor of Chicago, "Tony Baloney." Huey Long called Joseph E. Ransdell, his elderly opponent for Senator, "Old Feather Duster." Joe McCarthy liked to call Secretary of State Dean Acheson "The Red Dean of Fashion." Using epithets and other funny insults distracts followers' attention from seriously thinking about how to solve important public issues, getting easy laughs instead.

Rude and shocking behavior

Legislative bodies (like parliaments or congresses) usually have calm standards of behavior that are meant to quiet strong feelings and encourage careful discussion. Many demagogues break these standards in shocking ways. They do this to clearly show they are disrespecting the established order and the polite ways of the upper class, or simply because they enjoy the attention it brings. Ordinary people might find the demagogue disgusting, but the demagogue can use the upper class's dislike for him to show that he won't be shamed or scared by powerful people.

For example, Huey Long famously wore pajamas to very formal events where others were dressed very elegantly. Long was "intensely and solely interested in himself. He had to dominate every scene he was in and every person around him. He craved attention and would go to almost any length to get it. He knew that an audacious action, although it was harsh and even barbarous, could shock people into a state where they could be manipulated." He was "...so shameless in his pursuit of publicity, and so adept at getting press coverage, that he was soon attracting more attention from the press and the galleries than most of the rest of his colleagues combined."

In ancient Greece, Aristotle pointed out Cleon's bad manners more than 2,000 years ago: "[Cleon] was the first who shouted on the public platform, who used abusive language and who spoke with his cloak girt about him, while all the others used to speak in proper dress and manner."

Acting like an ordinary person

Demagogues often pretend to be down-to-earth, ordinary citizens, just like the people whose votes they want. In the United States, many took folksy nicknames: William H. Murray (1869–1956) was "Alfalfa Bill"; James M. Curley (1874–1958) of Boston was "Our Jim"; Ellison D. Smith (1864–1944) was "Cotton Ed"; the husband-and-wife demagogue team of Miriam and James E. Ferguson went by "Ma and Pa"; Texas governor W. Lee O'Daniel (1890–1969) was "Pappy-Pass-the-Biscuits."

Georgia governor Eugene Talmadge (1884–1946) put a barn and a henhouse on the executive mansion grounds. He loudly explained that he couldn't sleep at night unless he heard the sounds of farm animals. When he was with farmers, he chewed tobacco and faked a rural accent, even though he was college-educated. He would complain about "frills." Talmadge defined "furriner" (foreigner) as "Anyone who attempts to impose ideas that are contrary to the established traditions of Georgia." His grammar and vocabulary became more refined when speaking to city audiences. Talmadge was famous for wearing bright red galluses (suspenders), which he would snap for emphasis during his speeches. On his desk, he kept three books that he loudly told visitors were all a governor needed: a bible, the state financial report, and a Sears–Roebuck catalog.

Huey Long emphasized his humble beginnings by calling himself "The Kingfish" and drinking pot likker (liquid from cooked greens) when visiting northern Louisiana. He once sent out a press release demanding that his name be removed from the Washington Social Register. "Alfalfa Bill" made sure to remind people of his rural background by talking in farming terms: "I will plow straight furrows and blast all the stumps. The common people and I can lick the whole lousy gang."

Making things too simple

Demagogues often treat complicated problems, which need careful thought and analysis, as if they come from one simple cause or can be solved by one simple fix. For example, Huey Long claimed that all of the U.S.'s economic problems could be solved just by "sharing the wealth." Hitler claimed that Germany had lost World War I only because of a "Stab in the Back." Blaming others (above) is one way of making things too simple.

Attacking the news media

Because factual information reported by the press can weaken a demagogue's hold over followers, modern demagogues have attacked the press very strongly. They might call for violence against newspapers that opposed them, claim that the press was secretly working for rich interests or foreign powers, or say that leading newspapers were just personally trying to get them. Huey Long accused the New Orleans Times–Picayune and Item of being "bought," and had his bodyguards rough up their reporters. Oklahoma governor "Alfalfa Bill" Murray (1869–1956) once called for a bomb to be dropped on the offices of the Daily Oklahoman. Joe McCarthy accused The Christian Science Monitor, the New York Post, The New York Times, the New York Herald Tribune, The Washington Post, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and other leading American newspapers of being "Communist smear sheets" controlled by the Kremlin.

Demagogues in power

The shortest way to ruin a country is to give power to demagogues.

—Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Antiquities of Rome, VI (20 BC)

Taking over and breaking laws

When in a powerful executive office, demagogues often quickly try to increase their power. They do this both officially (by passing laws to expand their authority) and unofficially (by building networks of corruption and informal pressure to make sure their orders are followed, no matter what the constitution says).

For example, within two months of becoming chancellor, Hitler removed all constitutional limits on his power. He did this through almost daily acts of chaos, making the state unstable and giving stronger and stronger reasons to justify taking more power. Hitler was appointed on January 30, 1933. On February 1, the Reichstag (German parliament) was dissolved. On February 27, the Reichstag building burned. On February 28, the Reichstag Fire Decree gave Hitler emergency powers and suspended civil liberties. On March 5, new general elections were held. On March 22, the first concentration camp opened, taking political prisoners. On March 24, the Enabling Act was passed, giving Hitler full law-making powers. This ended all constitutional limits and made Hitler an absolute dictator. He continued to gain power even after that.

Even local demagogues have created one-person rule, or something very close to it, over their areas. "Alfalfa Bill" Murray, a demagogue elected governor of Oklahoma by appealing to poor rural people against "greedy rich people," promised to "make an open season on millionaires." Even though he had led Oklahoma's constitutional convention, Murray often broke the constitution. He ruled by executive order whenever the legislature or courts got in his way. When federal courts ruled against him, he won by using the National Guard. He even wore a military hat and pistol and personally commanded the troops, making sure the event was filmed by movie cameras. Murray tried to expand the governor's powers with four new ideas: replacing existing income-tax law with his own, giving him power to appoint all members of the board of education, taking land owned by corporations, and giving him huge power over the budget, but these were defeated.

Appointing unqualified friends; corruption

Demagogues often appoint people to high office based on personal loyalty, without caring if they are good at the job. This opens up many ways for dishonest gain and corruption. During "Alfalfa Bill" Murray's campaign for governor, he promised to crack down on corruption and favoritism for the rich. He also promised to get rid of half the clerk jobs at the State House, not to appoint family members, to reduce the number of state-owned cars from 800 to 200, never to use prison labor to compete with regular workers, and not to misuse the power to pardon. Once in office, he appointed wealthy supporters and 20 of his relatives to high office, bought more cars, used prisoners to make ice for sale and clean the capitol building, and broke all his other promises. When the State Auditor pointed out that 1,050 new employees had been added to the state payroll, Murray simply said, "Just damned lies." For each abuse of power, Murray claimed he had a mandate from "the sovereign will of the people."

Famous historical demagogues

Ancient history

Cleon

The Athenian leader Cleon is often called a demagogue because of three events described in the writings of Thucydides and Aristophanes.

First, after a failed revolt by the city of Mytilene, Cleon convinced the Athenians to kill not just the Mytilenean prisoners, but every man in the city, and sell their wives and children as slaves. The Athenians changed their minds the next day when they thought more clearly.

Second, after Athens had completely defeated the Peloponnesian fleet in the Battle of Sphacteria, and Sparta was begging for peace, Cleon convinced the Athenians to reject the peace offer.

Third, he made fun of the Athenian generals for not ending the war in Sphacteria quickly. He accused them of being cowards and said he could finish the job himself in twenty days, even though he knew nothing about the military. They gave him the job, expecting him to fail. Cleon was scared to make good on his boast and tried to get out of it, but he was forced to take command. He actually succeeded, by getting the general Demosthenes to do it. He treated Demosthenes with respect after previously slandering him. Three years later, Cleon and his Spartan opponent Brasidas were killed at the Battle of Amphipolis. This allowed peace to return until the Second Peloponnesian War started.

Modern historians believe that Thucydides and Aristophanes might have exaggerated how bad Cleon really was. Both had personal disagreements with Cleon, and The Knights is a funny play that doesn't even mention Cleon by name. Cleon was a tradesman, a leather-tanner. Thucydides and Aristophanes came from the upper classes, and they tended to look down on people from the business classes. Nevertheless, their descriptions define the classic example of a "demagogue" or "rabble-rouser."

Alcibiades

Alcibiades convinced the people of Athens to try to conquer Sicily during the Peloponnesian War. This led to terrible results. He led the Athenian assembly to support making him commander by claiming victory would be easy. He appealed to Athenian pride and pushed for action and courage over careful thought. Alcibiades's expedition might have succeeded if he had not been removed from command by his rivals' political tricks.

Gaius Flaminius

Gaius Flaminius was a Roman consul most known for being defeated by Hannibal at the Battle of Lake Trasimene during the second Punic war. Hannibal was able to make key decisions during this battle because he understood his opponent. Flaminius was described as a demagogue by Polybius in his book The Histories: "...Flaminius possessed a rare talent for the arts of demagogy..." Because Flaminius was not well-suited for command, he lost 15,000 Roman lives, including his own, in the battle.

Modern era

Adolf Hitler

The most famous demagogue of modern history, Adolf Hitler, first tried to overthrow the Bavarian government by force in a failed attempt in 1923. While in prison, Hitler chose a new plan: to overthrow the government democratically, by building a mass movement. Even before his failed attempt, Hitler had rewritten the Nazi party's goals to specifically target the lower classes of Germany. He appealed to their anger at wealthier classes and called for German unity and more central power. Hitler was very happy with the sudden increase in popularity.

While Hitler was in prison, the Nazi party's votes had fallen to one million, and they continued to fall after Hitler was released in 1924 and started to rebuild the party. For the next several years, Hitler and the Nazi party were generally seen as a joke in Germany, no longer taken seriously as a threat. The prime minister of Bavaria lifted the region's ban on the party, saying, "The wild beast is checked. We can afford to loosen the chain."

In 1929, with the start of the Great Depression, Hitler's populism began to work. Hitler updated the Nazi party's goals to take advantage of the economic hardship of ordinary Germans. He rejected the Versailles Treaty, promised to get rid of corruption, and pledged to give every German a job. In 1930, the Nazi party went from 200,000 votes to 6.4 million, making it the second-largest party in Parliament. By 1932, the Nazi party had become the largest in Parliament. In early 1933, Hitler was appointed Chancellor. He then used the Reichstag fire to arrest his political opponents and gain control of the army. Within a few years, using the democratic support of the masses, Hitler turned Germany from a democracy into a total dictatorship.

Huey Long

Huey Long, nicknamed "The Kingfish," was an American politician. He served as the 40th governor of Louisiana from 1928 to 1932 and as a member of the United States Senate from 1932 until he was killed in 1935. He was a populist member of the Democratic Party and became nationally famous during the Great Depression. He openly criticized President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal from a left-wing point of view. As the political leader of Louisiana, he had many supporters and often took strong actions. Long was a controversial figure; he is celebrated as a populist who helped ordinary people or criticized as a fascist demagogue.

In 1928, even before Long became governor of Louisiana, he was already overseeing political appointments to make sure he had loyal support for all his plans. As governor, he removed public officials who were not personally loyal to him. He took control away from state commissions to ensure that all contracts would be given to people in his political machine. In a disagreement over natural gas with managers of the Public Service Corporation, he told them, truthfully, "A deck has 52 cards and in Baton Rouge I hold all 52 of them and I can shuffle and deal as I please. I can have bills passed or I can kill them. I'll give you until Saturday to decide." They gave in to Long and became part of his growing political machine.

When Long became a senator in 1932, his enemy, Lieutenant Governor Paul N. Cyr, was sworn in as governor. Long, without official power, ordered state troopers to surround the governor's mansion and arrest Cyr as an imposter. Long put his ally Alvin O. King in as governor, who was later replaced by O.K. Allen. These governors served as puppets for Long. So, even in Washington, without official authority, Long kept dictatorial control over Louisiana. When the Mayor of New Orleans, T. Semmes Walmsley, began to oppose Long's extreme power over the state, Long used a judge who supported him to justify an armed attack, claiming he was cracking down on illegal activities. By Long's order, Governor Allen declared martial law and sent National Guardsmen to seize the Registrar of Voters, supposedly "to prevent election frauds." Then, by stuffing ballot boxes, Long made sure his chosen candidates won elections for Congress. Long's own illegal operations then grew. With his loyal legislature, armed militias, taxes used as a political weapon, control over elections, and weakened court authority to limit his power, Huey Long kept control in Louisiana similar to that of Hitler in Germany or Stalin in the Soviet Union.

Joseph McCarthy

Joseph McCarthy was a U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 to 1957. Although he wasn't a great speaker, McCarthy became nationally famous in the early 1950s by claiming that high-ranking officials in the United States federal government and military were "filled" with communists. This contributed to the second "Red Scare" (a period of intense fear of communism). Eventually, his inability to provide proof for his claims, as well as his public attacks on the United States Army, led to the Army–McCarthy hearings in 1954. These hearings, in turn, led to his official criticism by the Senate and a loss of popularity.

Can demagoguery be good?

Strategic demagoguery

Some experts have questioned the idea that demagoguery is always a bad type of leadership and speaking. For example, in Demagogues in American Politics, Charles U. Zug argues that demagoguery can be fair and even good if it's part of a larger plan for political change and if it's supported by strong reasons for that change. Zug compares older ideas about demagoguery, which assumed that demagogues had bad intentions (like wanting too much power), with a modern view that focuses on the public words and actions demagogues use to achieve political goals.

Similarly, Melissa Lane, a classicist from Princeton, has argued that in ancient times before Socrates, demagogues were not seen as naturally good or bad. Instead, they were viewed as supporters of the common people (as opposed to the wealthy few). Zug has argued that thinking of demagoguery as always negative encourages politicians to unfairly label others as "demagogues." As a result, innocent people, like the supposed leader of Shays' Rebellion, Daniel Shays, can be wrongly called vicious, dishonest leaders.

Demagoguery in official roles

Zug also argues that demagoguery means different things when used by public officials in different government roles. For example, American federal judges should be watched more carefully for using demagoguery than lawmakers should. This is because judging well (solving legal disputes) doesn't require directly appealing to the public. In contrast, being an effective member of Congress requires speaking up for the people they represent and getting re-elected. These responsibilities, in turn, sometimes require direct public appeals, and sometimes, demagoguery.

See also

In Spanish: Demagogo para niños

In Spanish: Demagogo para niños

- Authoritarianism

- Big lie

- Charismatic authority

- Cleophon

- Cult of personality

- Demades

- Firehosing

- Hyperbolus

- It Can't Happen Here

- Lachares

- Majoritarianism

- Narcissistic leadership

- Ochlocracy

- Social dominance orientation

- Strongman (politics)

- Toxic leader

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |