Edith Hamilton facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Edith Hamilton

|

|

|---|---|

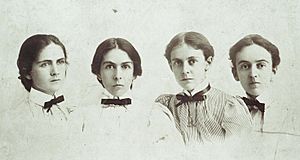

Hamilton c. 1897

|

|

| Born | August 12, 1867 Dresden, North German Confederation |

| Died | May 31, 1963 (aged 95) Washington, D.C. |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | American |

| Period | 1930–1957 |

| Subject | Ancient Greece Greek philosophy Mythology |

| Notable works | The Greek Way, The Roman Way, The Prophets of Israel, Mythology |

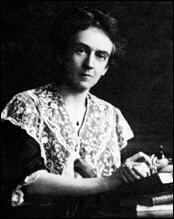

Edith Hamilton (born August 12, 1867 – died May 31, 1963) was an American teacher and a very famous author. She was known around the world as one of the best experts on ancient Greek and Roman cultures in her time.

Edith Hamilton went to Bryn Mawr College and also studied in Germany at the University of Leipzig and the University of Munich. She started her career as a teacher and later became the head of the Bryn Mawr School, a private school for girls in Baltimore, Maryland. But Edith Hamilton is most famous for her essays and popular books about ancient Greek and Roman civilizations.

Hamilton started her second career as an author after she retired from the Bryn Mawr School in 1922. She was 62 years old when her first book, The Greek Way, was published in 1930. It was an instant success! Her other well-known books include The Roman Way (1932), The Prophets of Israel (1936), Mythology (1942), and The Echo of Greece (1957).

Experts have praised Hamilton's books because they make ancient cultures feel alive and exciting. She is described as a scholar who "brought into clear and brilliant focus the Golden Age of Greek life and thought." Her writing style was powerful and simple. People say her books help modern readers find "refuge and strength in the past" during "troubled present" times. Edith's younger sister was Alice Hamilton, a pioneer in studying how workplaces affect health. Alice was also the first woman to become a professor at Harvard University.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Childhood and Family

Edith Hamilton was the oldest child of Gertrude Pond (1840–1917) and Montgomery Hamilton (1843–1909). She was born on August 12, 1867, in Dresden, Germany. Soon after she was born, her family moved back to the United States. They settled in Fort Wayne, Indiana, where Edith's grandfather, Allen Hamilton, had lived since the 1820s. Edith grew up in Fort Wayne, surrounded by her extended family.

Her grandfather, Allen Hamilton, was an Irish immigrant who came to Indiana in 1823. He became a successful businessman and bought a lot of land in Fort Wayne. Much of the city was built on land he once owned. The Hamilton family had a large estate in downtown Fort Wayne with three homes. They also built a summer home on Mackinac Island, Michigan, where they spent many summers. Edith's family, along with her aunts, uncles, and cousins, mostly lived on money they had inherited.

Edith's father, Montgomery Hamilton, loved to study but didn't work much. He went to Princeton University and Harvard Law School and also studied in Germany. He met Gertrude Pond, whose father was a rich businessman, while in Germany. They married in 1866. Montgomery Hamilton later joined a grocery business in Fort Wayne, but it failed in 1885, causing the family to lose money. After this, he stopped being involved in public life. Edith's mother, Gertrude, loved modern books and spoke several languages. She was very active in the community and had "wide cultural and intellectual interests." After her father's business failed, Edith realized she would need to earn her own living. She decided to become a teacher.

Edith was the oldest of five children. She had three sisters: Alice (1869–1970), Margaret (1871–1969), and Norah (1873–1945). She also had a brother, Arthur "Quint" (1886–1967). All of them became successful in their fields. Edith became a famous teacher and author. Alice helped create the field of industrial medicine. Margaret, like Edith, became a teacher and headmistress at the Bryn Mawr School. Norah was an artist. Edith's youngest sibling, Arthur, was 19 years younger than her. He became a writer, a professor of Spanish, and an assistant dean at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Arthur was the only sibling to marry, but he and his wife had no children.

Education

Edith's parents didn't like the public school system, so they taught their children at home. Edith once said, "My father was well-to-do, but he wasn't interested in making money; he was interested in making people use their minds." Edith learned to read very early and was an excellent storyteller. She gave her father credit for guiding her to study the classics. He started teaching her Latin when she was seven years old. Her father also introduced her to Greek language and literature. Her mother taught the children French and they had tutors for German.

In 1884, Edith started two years of study at Miss Porter's Finishing School for Young Ladies (now Miss Porter's School) in Farmington, Connecticut. Going to this school was a family tradition for the Hamilton women. Three of Edith's aunts, three cousins, and her three sisters also attended the school.

Hamilton returned to Indiana in 1886 and spent four years preparing for college. In 1891, she was accepted at Bryn Mawr College near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She studied Greek and Latin and earned a Bachelor of Arts and a Master of Arts degree in 1894. After graduation, Hamilton spent a year as a Latin fellow at Bryn Mawr College. She then received the Mary E. Garrett European Fellowship, the college's highest honor. This award gave Edith and Alice (who had finished her medical degree in 1893) money to study further in Germany for a year. Hamilton became the first woman to enroll at the University of Munich.

Studies in Germany

In the fall of 1895, the Hamilton sisters went to Germany. Alice planned to continue her studies in pathology at the University of Leipzig, and Edith wanted to study the classics and attend lectures. At that time, most North American women, including Edith and Alice, could only attend classes as "auditors," meaning they could listen but not officially participate. When they arrived in Leipzig, they found many foreign women studying at the university. They were told that women could attend lectures but were expected to be "invisible" and not join discussions.

Alice said that "Edith was extremely disappointed with the lectures she attended." Even though the lectures were detailed, they "lost sight of the beauty of literature by focusing on obscure grammatical points." So, they decided to go to the University of Munich, but it wasn't much better. At first, it was unclear if Edith would even be allowed to audit lectures there. She was given permission, but under strange conditions. Alice said that when Edith arrived at her first class, she was led to the lecture platform and seated in a chair next to the lecturer, facing the audience. This was done "so that nobody would be contaminated by contact with her." Edith reportedly said, "the head of the University used to stare at me, then shake his head and say sadly to a colleague, 'There now, you see what's happened? We're right in the midst of the woman question.'"

Career

Educator

Edith Hamilton had planned to stay in Munich, Germany, to earn a doctoral degree. However, her plans changed after Martha Carey Thomas, the president of Bryn Mawr College, convinced Hamilton to return to the United States. In 1896, Hamilton became the head administrator of Bryn Mawr School. This school was founded in 1885 as a college preparatory school for girls in Baltimore, Maryland. It was the only private high school for women in the country that prepared all its students for college. To graduate, students had to pass Bryn Mawr College's entrance exam.

Even though Hamilton never finished her doctorate, she became an "inspiring and respected head of the school." She was admired as an excellent teacher of the classics and a successful administrator. She improved student life, kept high academic standards, and brought new ideas. Hamilton was brave enough to suggest new things, like having her school's basketball team play against another girls' team from a nearby boarding school. This idea was considered scandalous at the time because news coverage would include the players' names. After Hamilton convinced the local newspapers not to cover the event, the games happened and became a yearly tradition.

In 1906, Hamilton's achievements as an educator were recognized when she was named the first headmistress in the school's history. Hamilton believed in giving students a "rigorous" (challenging) curriculum. She successfully transformed the girls' school from its "mediocre beginnings into one of the foremost preparatory institutions in the country." Her strong belief in challenging standards and different school policies led to disagreements with Dean Thomas. As Hamilton became more frustrated with the situation at the school, her health also suffered. She retired in 1922 at the age of 54, after 26 years of working at the school.

Classicist and Author

After retiring as a teacher in 1922 and moving to New York City in 1924, Hamilton started a new career. She became an author, writing essays and popular books about ancient Greek and Roman civilizations. She had studied Greek and Latin since she was young, and it remained her lifelong interest. "I came to the Greeks early," Hamilton told an interviewer when she was 91, "and I found answers in them."

For more than 50 years, her "love affair with Greece had smoldered without literary outlet" (meaning she loved the topic but hadn't written about it for the public). At the suggestion of Rosamund Gilder, an editor, Hamilton began by writing essays about Greek plays and comedies. Several of her early articles were published before she started writing the series of books on ancient Greek and Roman life that made her famous. Hamilton became America's most renowned expert on the classics of her time.

According to her biographer, Barbara Sicherman, Hamilton's life was "ruled by a passionately nonconformist vision" (a strong and unique way of looking at the world). This was also the source of her "strength and vitality" and her appeal as a public figure and author. However, Hamilton was not, and didn't claim to be, a traditional scholar. She didn't try to present too many detailed facts from the past. Instead, Hamilton focused on making her books easy to read and finding "truths of the spirit," which she discovered from ancient writers. Drawing from Greek, Roman, Hebrew, and early Christian writings, Hamilton described what ancient people were like by focusing on what they wrote about their own lives. She tried to copy the directness and perfection of ancient writers and did not include footnotes.

- The Greek Way

Hamilton was 62 when her first book, The Greek Way, was published in 1930. Some consider it her most honored work. The successful book, which Hamilton wrote after an editor encouraged her, made her a well-known author in the United States. This bestseller compared ancient Greece to modern life, with essays about famous figures from Athenian history and literature. Critics praised the book for its "vivid and graceful prose," which brought Hamilton immediate fame and established her reputation as a scholar. One biographer said that "The Greek Way makes the ancient Greek mind easy for modern readers to understand."

Hamilton believed that Greek civilization at its peak was a "flowering of the mind" that has never been equaled. The Greek Way showed that the Greeks valued things like love, athletic games, knowledge, fine arts, and intelligent conversation. In the first chapter, "East and West," Hamilton described the differences between the West and the Eastern nations that came before it. She suggested that the modern spirit of the West was "a Greek discovery, and the place of the Greeks is in the modern world."

More recent writers have used Hamilton's observations to compare Eastern and Western cultures. For example, when comparing ancient Egypt with Greece, Hamilton's writing describes their unique geography, climate, farming, and government. Historian James Golden quotes from The Greek Way that "Egyptian society was preoccupied with death." Its pharaohs built huge monuments to themselves, and priests told slaves to "look forward to an afterlife." Golden used Hamilton's research to contrast this with the Greeks, especially the Athenians. Hamilton argued that individual "perfection of mind and body" was central to Greek thought. As a result, the Greeks "excelled at philosophy and sports," and life "in all its exuberant potential" (full of life and possibilities) was a key part of Greek civilization.

- The Roman Way

The Roman Way (1932), her second book, also compared ancient Rome to present-day life. It was also chosen by the Book-of-the-Month Club in 1957. Hamilton described life as it was seen by ancient Roman poets like Plautus, Virgil, and Juvenal. She explained Roman ideas and customs and compared them to people's lives in the 20th century. She also suggested how Roman ideas still apply to the modern world.

Even though her books were successful, she admitted that "it was hopeless to persuade Americans to be Greeks." She felt that "life had become far too complex since the age of Pericles to recapture the simple directness of Greek life."

- The Prophets of Israel

Her later books covered other interesting topics, especially from the Bible. In 1936, Hamilton wrote The Prophets of Israel, which explained the beliefs of the "spokesmen for God" in the Old Testament. She didn't know Hebrew, so she used English versions of the Bible. She compared the achievements and lives of the prophets to those of 20th-century readers. She concluded that the prophets were practical and their political views fit their time, but their ideals were modern.

Hamilton also explained how this connection is important to people today: "Love and grief and joy remain the same forever beautiful" and "poetic truth is always true," as are truths of the spirit. "The prophets understand them as no men have more, and in their pages we can find ourselves." A later edition of the book, Spokesmen for God: The Great Teachers of the Old Testament (1949), added more comments on the first five books of the Old Testament.

- Mythology

John Mason Brown, an American drama critic, praised Hamilton's The Greek Way as one of the best modern books about ancient Greece. He also said Mythology was much better than other books on the subject. Hamilton's Mythology (1942) tells the stories of classical mythology and ancient fables. She approached mythology entirely through ancient literature. (She didn't travel to Greece until 1929 and was not an archaeologist.) The book received good reviews, was another Book-of-the-Month Club selection, and had sold more than 4.5 million copies by 1957.

- Later Works

In 1942, after moving to Washington, D.C., Hamilton continued to write. At the age of 82, she offered new ideas about the New Testament in Witness to the Truth: Christ and His Interpreters (1948). She also wrote a follow-up to The Greek Way, called The Echo of Greece (1957). This book discusses the political ideas of teachers and leaders like Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, Demosthenes, and Alexander the Great.

Hamilton continued traveling and giving lectures in her eighties. She also wrote articles, reviews, and translated Greek plays, including The Trojan Women, Prometheus Bound, and Agamemnon. She also helped edit The Collected Dialogues of Plato (1961).

Companion Doris Reid

Doris Fielding Reid (1895–1973) was an American stockbroker. She was the daughter of Harry Fielding Reid, a geophysicist, and Edith Gittings Reid, who wrote biographies. Doris was a student of Edith Hamilton. Reid worked for an investment company starting in 1929. Reid and Hamilton became lifelong companions. They lived together in Gramercy Park, Manhattan, and Sea Wall, Maine. During this time, they raised and home-schooled Reid's nephew, Francis Dorian Fielding Reid. After Hamilton's death, Reid published a book called Edith Hamilton: An Intimate Portrait (1967). Reid died on January 15, 1973. Both women are buried at Cove Cemetery in Hadlyme, Connecticut.

Later Years and Honors

Hamilton and Doris Reid lived in New York City until 1943, then moved to Washington, D.C.. They spent their summers in Maine. In Washington, Reid managed the local offices of an investment firm. Hamilton continued to write and often hosted friends, writers, government officials, and other important guests at her home. Famous visitors included Isak Dinesen, Robert Frost, and labor leader John L. Lewis.

After moving to Washington, Hamilton became a commentator on education projects and started receiving honors for her work. She also recorded programs for television and Voice of America, traveled to Europe, and continued to write books, articles, and reviews.

Hamilton considered a trip to Greece at age 90 in 1957 to be the highlight of her life. In Athens, she saw her translation of Aeschylus's Prometheus Bound performed at the ancient Odeon theater. As part of the evening's ceremonies, King Paul of Greece gave her the Golden Cross of the Order of Benefaction—one of Greece's highest honors. The mayor of Athens made her an honorary citizen of the city. News media in the US, including Time magazine, covered the event. An article described the event in Hamilton's honor: floodlights lit up the Parthenon, the Temple of Zeus, and, for the first time, the Stoa. Hamilton called the ceremony "the proudest moment of my life."

Modern Influences

Many facts in The Greek Way (1930) have surprised modern readers. One reviewer explained Hamilton's idea that "the spirit of our age is a Greek discovery, and that the Greeks were really the first Westerners, and the first intellectualists." The reviewer also noted that Hamilton's book showed how modern ideas of play and sport were common activities for the Greeks. They enjoyed exercise and athletic events, including games, races, music, dancing, and wrestling competitions.

One person influenced by Hamilton's writings was U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy. In the months after his brother, President John F. Kennedy, died, Robert was very sad. Former First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy gave him a copy of The Greek Way, believing it would help him. A political commentator reported that Hamilton's essays helped him understand and recover from his brother's tragic death. Hamilton's writings remained important to him and changed Kennedy's life. He carried his worn, underlined copy with him for years, reading parts aloud and could recite passages from Aeschylus that Hamilton had translated.

Reviewers said that Hamilton's The Prophets of Israel (1936) was similar to her earlier books about Greeks and Romans. It made the prophets' messages important to readers today. She did this by showing that "behind all great thought stands an individual mind, fired by passion and possessed of an eye that sees deeply into humanity." The views of the prophets, it adds, are very similar to those in modern times.

Death

Hamilton died in Washington, D.C., on May 31, 1963, when she was almost 96 years old. Four years after her death, Doris Fielding Reid published Edith Hamilton: An Intimate Portrait. As of 2017, this book is still the only full biography of Hamilton.

Reid died on January 15, 1973. Both women are buried at Cove Cemetery in Hadlyme, Connecticut. This is the same cemetery where Hamilton's mother, her sisters (Alice, Norah, and Margaret), and Margaret's close friend, Clara Landsberg, are buried. Hamilton's adopted son, Dorian, who studied chemistry, died in January 2008, at age 90.

Legacy

Hamilton was recognized as a great expert on the classics of her time. Her popular books were especially notable because they were easy for many people to read. They also presented the Greeks as an important source of cultural inspiration for American society before and after World War II.

Although Hamilton's fame as an author is mostly linked to her writings about Greece, much of her professional life focused on Latin. She "claimed special expertise in Greek," but after graduating from Bryn Mawr College, where she studied Greek and Latin, she spent another year there as a Latin fellow and another year studying Latin in Germany. Hamilton also taught Latin to high school girls during her 26-year career at Bryn Mawr School. However, except for The Roman Way, Hamilton's written works mainly focused on Athens in the 4th and 5th centuries BC. Hamilton's letters and papers are kept at the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College.

Honors and Recognition

In 1906, Hamilton became the first headmistress of the Bryn Mawr School in Baltimore, Maryland.

In 1950, Hamilton received honorary degrees (Doctor of Letters) from the University of Rochester and the University of Pennsylvania. She also received an honorary degree from Yale University in 1960. In addition, Hamilton was chosen to be part of the American Institute of Arts and Letters in 1955 and the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1957.

Hamilton received the National Achievement Award in 1951. This award honored her as a distinguished classical scholar and author. She received the award along with Anna M. Rosenberg, Assistant Secretary of Defense. The award was created in 1930 to honor accomplished women and inspire others.

Hamilton was given the Golden Cross of the Order of Benefaction, Greece's highest honor, and became an honorary citizen of Athens in 1957.

In 1957 and 1958, she was interviewed by NBC television. In 1957, The Greek Way and The Roman Way were chosen by the Book of the Month Club as summer readings. John F. Kennedy invited her to his inauguration, but she declined. He also sent a representative to her home to ask for advice about a new cultural center.

In 1958, the Women's National Book Association gave her an award for her contributions to American culture through books. George V. Allen, director of the United States Information Agency (USIA), said that her explanation of the democratic spirit of ancient Greece defined "the fundamental of the democratic ideal itself." He also noted that USIA included seven of her books in its overseas libraries to help people in other countries understand American ideals.

Doris Fielding Reid wrote a biography about her, called Edith Hamilton: An Intimate Portrait.

Robert F. Kennedy quoted from Hamilton's translated works in what is perhaps his most memorable speech. This was during a campaign rally on April 4, 1968, in Indianapolis, Indiana, as sad news spread across the country. Kennedy quoted from memory several lines from Hamilton's translation of Aeschylus's tragedy, Agamemnon, telling the grieving crowd: "In our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God." Kennedy also used another line from Hamilton's writing, "her representation of an ancient Greek inscription," in his closing remarks: "Let us dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago––to tame the savageness of man and make gentle the life of this world." According to one expert, that line about "taming the savageness of man" was created by Hamilton herself, combining ideas from different ancient texts.

In 2000, the city of Fort Wayne, Indiana, put up statues of two Hamilton sisters, Edith and Alice, along with their cousin, Agnes, in the city's Headwaters Park.

Selected Published Works

- The Greek Way (1930)

- The Roman Way (1932)

- The Prophets of Israel (1936)

- Three Greek Plays (1937)

- Mythology: Timeless Tales of Gods and Heroes (1942)

- The Great Age of Greek Literature (1942)

- Witness to the Truth: Christ and His Interpreters (1948)

- Spokesmen for God (1949)

- The Echo of Greece (1957)

- The Collected Dialogues of Plato, Including the Letters (1961), edited by Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns

- The Ever Present Past (1964), collected essays and reviews

See also

In Spanish: Edith Hamilton para niños

In Spanish: Edith Hamilton para niños