Fernando Pessoa facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Fernando Pessoa

|

|

|---|---|

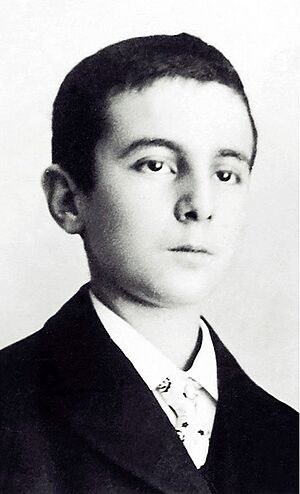

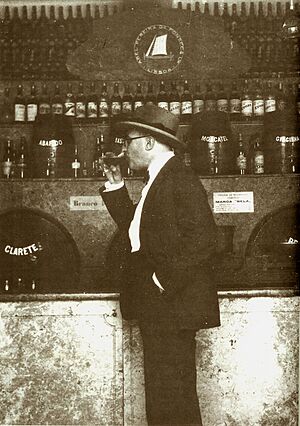

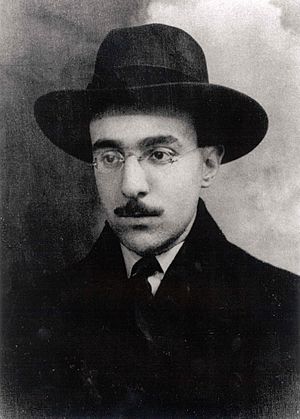

Portrait of Pessoa, 1914

|

|

| Born | Fernando António Nogueira Pessoa 13 June 1888 Lisbon, Portugal |

| Died | 30 November 1935 (aged 47) Lisbon, Portugal |

| Pen name | Alberto Caeiro, Álvaro de Campos, Ricardo Reis, Bernardo Soares, etc. |

| Occupation |

|

| Language | Portuguese, English, French |

| Nationality | Portuguese |

| Citizenship | Portuguese |

| Period | 1912–1935 |

| Genre | Poetry, essay, fiction |

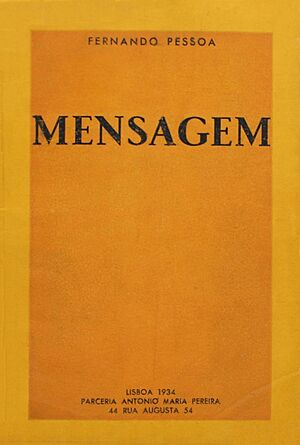

| Notable works | Mensagem (1934) The Book of Disquiet (1982) |

| Notable awards |

|

| Partner | Ofélia Queirós (girlfriend) |

| Signature | |

Fernando António Nogueira Pessoa (13 June 1888 – 30 November 1935) was a famous Portuguese poet, writer, and philosopher. Many people consider him one of the most important writers of the 20th century and one of the greatest poets in the Portuguese language. He also wrote and translated works in English and French.

Pessoa was a very busy writer. He didn't just write under his own name. He created about seventy-five other writing personalities. Three of these were very famous: Alberto Caeiro, Álvaro de Campos, and Ricardo Reis. He called them heteronyms instead of pseudonyms. This was because he felt they were like real, independent people with their own thoughts and lives. These imaginary characters sometimes had unusual or strong opinions.

Contents

Early Life of Fernando Pessoa

Fernando Pessoa was born in Lisbon, Portugal, on June 13, 1888. When he was five years old, his father, Joaquim de Seabra Pessôa, died from tuberculosis. The next year, his younger brother Jorge, who was only one, also passed away.

After his mother, Maria Magdalena Pinheiro Nogueira, married again, Fernando moved with her to South Africa in early 1896. His stepfather was a military officer who became the Portuguese consul in Durban. Durban was the capital of the British Colony of Natal at that time.

The young Pessoa went to St. Joseph Convent School, a Roman Catholic school run by Irish and French nuns. In April 1899, he started at the Durban High School. There, he became very good at English and learned to love English literature. In November 1903, he won the Queen Victoria Memorial Prize for the best English paper in a big exam. While getting ready for university, he also took night classes at the Durban Commercial High School.

During this time, Pessoa began writing short stories in English. Some of these he wrote under the name David Merrick, but many were never finished. When he was sixteen, a newspaper called The Natal Mercury published his poem "Hillier did first usurp the realms of rhyme..." on July 6, 1904. He signed it as C. R. Anon (anonymous). In December, The Durban High School Magazine published his essay "Macaulay". From February to June 1905, The Natal Mercury also published at least four of his sonnets. These included "Joseph Chamberlain" and "To England I". Pessoa started using pen names when he was very young. His first one was Chevalier de Pas. He also used names like Horace James Faber and Alexander Search.

Ten years after arriving in South Africa, Pessoa left Durban for good at age seventeen. He sailed back to Lisbon through the Suez Canal. This journey later inspired two of his poems, "Opiário" and "Ode Marítima". These were published in 1915 under his heteronym Álvaro de Campos.

Pessoa's Return to Lisbon

When Pessoa returned to Lisbon in 1905, his family stayed in South Africa. He planned to study diplomacy, but he got sick and had poor results for two years. A student strike against the government ended his formal studies. Pessoa then taught himself by reading many books at the library. In August 1907, he started working at an American business information agency.

His grandmother died in September and left him a small amount of money. He used this to start his own publishing company, "Empreza Ibis". This business didn't do well and closed in 1910. However, the name ibis, a sacred bird from Ancient Egypt, remained important to him.

Pessoa continued to study on his own, learning more about Portuguese culture. The political changes in Portugal, like the assassination of King Charles I in 1908 and the successful republican revolution in 1910, influenced his writing. His step-uncle, a poet, also introduced him to Portuguese poetry.

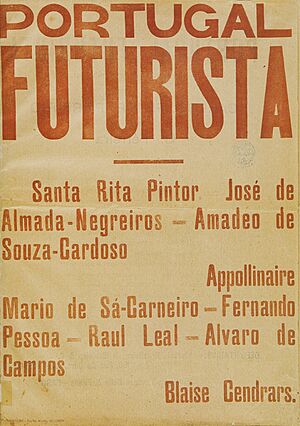

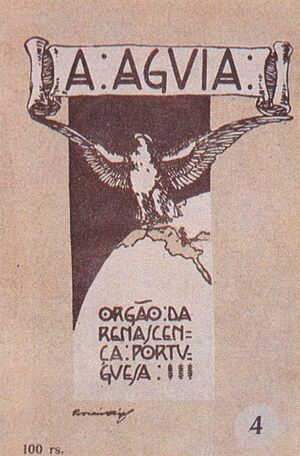

In 1912, Fernando Pessoa began his literary career with an essay in the journal A Águia. This essay started a big debate in Portuguese literature. In 1915, Pessoa and other artists and poets, including Mário de Sá-Carneiro, created the magazine Orpheu. This magazine brought modernist literature to Portugal. Only two issues were published because of money problems. Orpheu published works by Pessoa himself and his modernist heteronym, Álvaro de Campos.

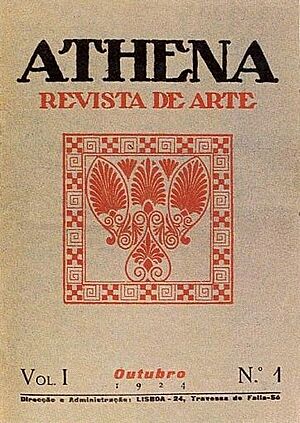

Pessoa also helped start the art journal Athena (1924–25). In this journal, he published poems under the heteronyms Alberto Caeiro and Ricardo Reis. Besides his job as a freelance translator, Fernando Pessoa wrote a lot. He was a literary critic and political analyst, writing for many journals and newspapers throughout his life.

Pessoa's Life in Lisbon

After returning to Portugal at age seventeen, Pessoa rarely left Lisbon. The city inspired his poems "Lisbon Revisited" (1923 and 1926), written by his heteronym Álvaro de Campos. From 1905 to 1920, he lived in fifteen different places in the city. He moved often because of his money situation and personal issues.

Pessoa created the character Bernardo Soares, one of his heteronyms. Soares was supposedly an accountant working in downtown Lisbon. Pessoa knew this area well from his long career as a freelance translator. From 1907 until his death in 1935, Pessoa worked for many different companies in Lisbon's downtown. In The Book of Disquiet, Bernardo Soares describes these typical places and their atmosphere. He wrote about Lisbon in the early 20th century, describing the crowds, buildings, shops, and even Fernando Pessoa himself.

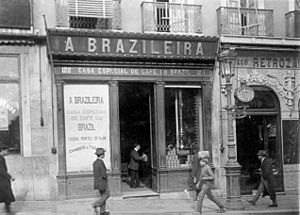

You can see a statue of Pessoa sitting at a table outside A Brasileira. This coffee house was a favorite spot for young writers and artists of the Orpheu group in the 1910s. It's close to Pessoa's birthplace in the elegant Chiado district. Later, Pessoa often visited Martinho da Arcada, another old coffee house, where he met friends.

In 1925, Pessoa wrote a guidebook to Lisbon in English, but it wasn't published until 1992.

Pessoa's Interest in Occultism

Pessoa translated many books. He translated Portuguese books into English. He also translated famous English works into Portuguese, like The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne and poems by Edgar Allan Poe. Poe, along with Walt Whitman, greatly influenced him.

Pessoa also translated books by leading theosophists like Helena Blavatsky.

From 1912 to 1914, Pessoa took part in "semi-spiritualist sessions" at home. His interest in spiritualism grew in 1915 while translating theosophist books. In March 1916, he started having experiences where he believed he became a medium. He even experimented with automatic writing, where he felt his arm moved without his control. He described these experiences in a letter to his aunt.

Pessoa also said he had "astral" or "etherial visions" and could see "magnetic auras." He was curious but also respectful of these strange events. He asked for secrecy because he felt there were "many disadvantages" to talking about them. Mediumship strongly influenced his writing. He felt "suddenly being owned by something else." When he looked in the mirror, he sometimes saw his "face fading out" and being replaced by the faces of his heteronyms.

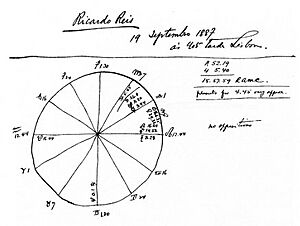

Pessoa also became very interested in astrology and was a skilled astrologer. He created hundreds of horoscopes for famous people like William Shakespeare and Napoleon I. In 1915, he created the heteronym Raphael Baldaya, an astrologer. Pessoa even made horoscopes for his heteronyms and journals like Orpheu.

Pessoa was born on June 13. The personalities of his main heteronyms were inspired by the four astral elements: air, fire, water, and earth. This meant Pessoa and his heteronyms together represented ancient knowledge. These heteronyms were designed according to their horoscopes, all including Mercury, the planet of literature. Astrology was part of his daily life, and he kept this interest until his death, which he predicted with some accuracy.

As a mysticist, Pessoa was very interested in esotericism, occultism, hermetism, numerology, and alchemy. Along with spiritualism and astrology, he also studied neopaganism, theosophy, rosicrucianism, and freemasonry. These ideas greatly influenced his literary work. He called himself a Pagan, meaning an "intellectual mystic." His interest in occultism led him to write to Aleister Crowley, another famous occultist.

Pessoa's Writing Style and Influences

In his early years, Pessoa was influenced by major English poets like Shakespeare and Milton. He also admired romantic poets such as Shelley and Byron. After returning to Lisbon in 1905, he was influenced by French symbolists and Portuguese poets like Cesário Verde. Later, he was also influenced by modernists like W. B. Yeats and James Joyce.

During World War I, Pessoa tried to get his English poems published in Britain, but they were refused. However, in 1920, a respected literary journal called Athenaeum published one of his poems. In 1918, Pessoa published two small books of English poems in Lisbon: Antinous and 35 Sonnets. In 1921, he published two more English poetry volumes. He also published books by his friends. His publishing house closed in 1923 after a scandal about some of the books it published.

Politically, Pessoa described himself as a "British-style conservative." This meant he was liberal within conservatism and against extreme reactions. He was also an outspoken elitist and against communism, socialism, fascism, and Catholicism. He supported the First Portuguese Republic at first. But when things became unstable, he supported military takeovers in 1917 and 1926 to bring back order. He wrote a pamphlet supporting the military government in 1928. However, after the New State was established in 1933, Pessoa became unhappy with the government. He wrote critically about Salazar (the leader) and fascism, opposing its censorship and control. In early 1935, Pessoa was banned by the Salazar government after he wrote in defense of Freemasonry. The government also stopped two articles where Pessoa criticized Mussolini's invasion of Abyssinia and fascism as a threat to freedom.

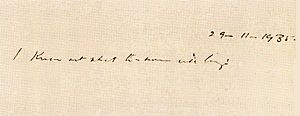

On November 29, 1935, Pessoa was taken to the hospital with stomach pain and a high fever. There, he wrote his last words in English: "I know not what tomorrow will bring." He died the next day, November 30, 1935, at age 47.

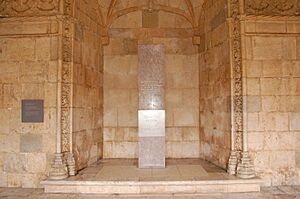

During his life, Pessoa published four books in English and only one in Portuguese: Mensagem (Message). However, he left behind a huge amount of unpublished writings in a wooden trunk. This included 25,574 manuscript and typed pages. These have been kept in the Portuguese National Library since 1988, and editing this large collection is still ongoing. In 1985, fifty years after his death, Pessoa's remains were moved to the Hieronymites Monastery in Lisbon. This is where other famous Portuguese figures like Vasco da Gama are buried. Pessoa's picture was also on the 100--escudo banknote.

Pessoa's Heteronyms

Pessoa's very first heteronym was Chevalier de Pas, created when he was just six years old. Other childhood heteronyms included Dr. Pancrácio and David Merrick. Later came Charles Robert Anon, a young Englishman who became Pessoa's alter ego. From 1905 to 1907, while Pessoa was a student, Alexander Search took Anon's place. Search was English but born in Lisbon, like Pessoa. He was a transition heteronym as Pessoa adjusted to Portuguese culture. After the republican revolution in 1910, Pessoa created another alter ego, Álvaro de Campos. Campos was supposedly a Portuguese naval engineer who studied in Glasgow.

The translator Richard Zenith notes that Pessoa created at least seventy-two heteronyms. According to Pessoa himself, there are three main ones: Alberto Caeiro, Álvaro de Campos, and Ricardo Reis. Pessoa's heteronyms are different from simple pen names. They have their own life stories, personalities, beliefs, appearances, writing styles, and even signatures. Because of this, the heteronyms often disagreed with each other and discussed literature, art, and philosophy.

Alberto Caeiro: The Simple Poet

Alberto Caeiro was Pessoa's first important heteronym. Pessoa described him as someone who "sees things with the eyes only, not with the mind." Caeiro doesn't let thoughts get in the way when he looks at a flower. A stone simply tells him it's a stone. This way of looking at things might seem "unpoetic," but Caeiro turned it into amazing poetry.

What makes Caeiro unique is how he understands life. He doesn't question anything; he calmly accepts the world as it is. His poems often show a childlike wonder at nature's variety. He is free from deep philosophical worries. For Caeiro, things are exactly what they seem; there's no hidden meaning.

He finds happiness by not asking questions, which helps him avoid doubts. He understands reality only through his senses. Octavio Paz called him the innocent poet. Paz noted that Caeiro "doesn't believe in anything. He exists."

Before Caeiro, poetry usually explained things. Poets would interpret their surroundings. Caeiro didn't do this. Instead, he tried to share his senses and feelings directly, without any interpretation.

Caeiro tried to experience nature in a new way: by simply perceiving it. Earlier poets used complex metaphors. Caeiro's goal was to show objects to the reader as directly and simply as possible. He wanted a direct experience of the things around him.

Critics have called Caeiro an anti-intellectual and an anti-poet. Caeiro simply is. He is very different from Fernando Pessoa, who was often troubled by deep questions. Caeiro avoided these worries by believing firmly that there was no hidden meaning behind things. For him, things just are.

Caeiro represents a basic, original way of seeing reality. He is like the spirit of paganism itself. The critic Jane M. Sheets believes that Caeiro was essential for Pessoa's later poetic characters. Through Caeiro, Pessoa gained a strong and universal poetic vision. After Caeiro's ideas were set, the voices of Campos, Reis, and Pessoa himself became more confident.

Ricardo Reis: The Calm Philosopher

In a letter, Pessoa wrote that to truly understand Ricardo Reis's "Odes," one would need to know Portuguese well. He said Reis's Portuguese would impress famous writers, and his style was like that of Horace. Someone even called him "a Greek Horace who writes in Portuguese."

Reis, a character and heteronym of Fernando Pessoa, summarized his life philosophy: "See life from a distance. Never question it. There's nothing it can tell you." Like Caeiro, whom he admired, Reis avoided questioning life. He was a modern pagan who encouraged people to enjoy the present and accept their fate calmly. He believed, "Wise is the one who does not seek. The seeker will find in all things the abyss, and doubt in himself." In this way, Reis was similar to Caeiro.

Reis believed in the Greek gods but lived in a Christian Europe. He felt his spiritual life was limited and true happiness was hard to find. This, along with his belief that Fate controls everything, led to his epicureanist philosophy. This philosophy suggests avoiding pain and seeking peace and calm above all else, staying away from strong emotions.

While Caeiro wrote freely and joyfully about his simple connection to the world, Reis wrote in a strict, intellectual way. His poems had a planned rhythm and structure. He paid close attention to using correct language when writing about themes like "the shortness of life, the pointlessness of wealth and struggle, the joy of simple pleasures, patience in hard times, and avoiding extremes."

His detached, intellectual approach was closer to Fernando Pessoa's constant thinking. Reis represented Pessoa's desire for balance and calmness, a world free of troubles. This was a strong contrast to Caeiro's spirit and style. While Caeiro's main feeling was joy, accepting sadness as natural, Reis was often sad about how everything changes and doesn't last.

Ricardo Reis is also the main character in José Saramago's 1986 novel The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis.

Álvaro de Campos: The Intense Dreamer

Álvaro de Campos is like a very exaggerated version of Pessoa himself. Of the three main heteronyms, he feels things the most strongly. His motto was "to feel everything in every way." He wrote, "The best way to travel is to feel." Because of this, his poetry is the most emotional and varied. He constantly balanced two main desires. On one hand, he had a strong wish to be and feel everything and everyone. He said, "in every corner of my soul stands an altar to a different god." This is similar to Walt Whitman's idea of "containing multitudes." On the other hand, he also wished for isolation and a feeling of nothingness.

As a result, his mood and beliefs changed a lot. Sometimes he was full of violent, energetic excitement, wanting to experience the whole universe within himself. In this state, he showed futuristic ideas, expressing great excitement about city life. Other times, he was in a state of sad nostalgia, seeing life as empty.

One of Campos's constant worries, as part of his changing personality, was his identity. He didn't know who he was, or he couldn't achieve his ideal identity. He wanted to be everything, and when he failed, he felt despair. Unlike Caeiro, who asked nothing of life, Campos asked too much.

Famous Works by Fernando Pessoa

Message

Mensagem (which means "Message"), written in Portuguese, is an epic poem with symbolic meanings. It has 44 short poems divided into three parts or Cycles:

The first part, "Brasão" (Coat-of-Arms), connects Portuguese historical figures to the parts of the Portuguese coat of arms. The first two poems are inspired by Portugal's physical and spiritual nature. Each of the other poems links a historical person to a part of the coat of arms. All these connections lead to the Golden Age of Discovery.

The second part, "Mar Português" (Portuguese Sea), talks about Portugal's Age of Exploration and its sea empire. This period ended with the death of King Sebastian in 1578. Pessoa brings the reader from a dream of the past to a dream of the future. He imagines King Sebastian returning, still determined to create a Universal Empire.

The third Cycle, "O Encoberto" ("The Hidden One"), describes Pessoa's vision of a future world of peace and the Fifth Empire. Pessoa believed this empire would be spiritual, not material. It would come after times of force and boredom, through understanding and the return of "The Hidden One," or "King Sebastian." The Hidden One represents the fulfillment of humanity's destiny and Portugal's purpose.

King Sebastian is very important in Mensagem. He appears in all three parts. He represents the ability to dream and believe that dreams can come true.

One of the most famous lines from Mensagem is from "O Infante": Deus quer, o homem sonha, a obra nasce (which means "God wishes, man dreams, the work is born"). Another well-known line is from "Ulysses": "O mito é o nada que é tudo" (meaning "The myth is the nothing that is all"). This poem talks about Ulysses, king of Ithaca, as the founder of Lisbon, based on an old Greek myth.

Literary Essays

In 1912, Fernando Pessoa wrote essays (later called The New Portuguese Poetry) for the cultural journal A Águia (The Eagle). This journal was started in Oporto in December 1910 by a group of republican thinkers. They wanted to renew Portuguese culture through a movement called Saudosismo. Pessoa wrote several papers for A Águia. These writings showed that Pessoa knew a lot about modern European literature. He believed that Portugal would soon produce a great poet who would make an important contribution to European culture and humanity.

Philosophical Essays

The philosophical notes Pessoa wrote when he was young, mostly between 1905 and 1912, show his interest in Philosophy. He explored many philosophical ideas and concepts. His writings varied in length, from a few lines to several pages.

Pessoa categorized philosophical systems in different ways. He discussed ideas like Pantheism, where God is everything, and Transcendentalism, which believes in a reality beyond what we can see. He thought that the most advanced philosophical system would accept contradictions as "the essence of the universe." He believed that a statement is truer the more contradiction it involves. He saw the philosophy of Hegel as a great example of this.

Pessoa used these philosophical ideas to describe the new poetry movement called Saudosismo. He also explored the social and political effects of adopting these ideas. He hinted that philosophy and religion try "to find in everything a beyond."

Works by Fernando Pessoa

- Antinous: a poem, Lisbon: Monteiro & Co., 1918.

- 35 Sonnets, Lisbon: Monteiro & Co., 1918.

- English Poems, 2 vol., Lisbon: Olisipo, 1921.

- Selected Poems, tr. Edwin Honig, Swallow Press, 1971.

- Selected Poems, tr. Peter Rickard, University of Texas Press, 1972.

- The Book of Disquiet (first published 1982; many translations exist).

- Fernando Pessoa: Self-Analysis and Thirty Other Poems, tr. George Monteiro, Gavea-Brown Publications, 1989.

- Message, tr. Jonathan Griffin, introduction by Helder Macedo, Menard Press, 1992.

- The anarchist banker and other Portuguese stories. Carcanet Press, 1996.

- The Keeper of Sheep, bilingual edition, tr. Edwin Honig & Susan M. Brown, Sheep Meadow, 1997.

- Fernando Pessoa & Co: Selected Poems, tr. Richard Zenith, Grove Press, 1999.

- Selected Poems: with New Supplement tr. Jonathan Griffin, Penguin Classics; 2nd edition, 2000.

- Sheep's Vigil by a Fervent Person: A Translation of Alberto Caeiro/Fernando Pessoa, tr. Erin Moure, House of Anansi, 2001.

- The Education of the Stoic, tr. Richard Zenith, afterword by Antonio Tabucchi, Exact Change, 2004.

- A Little Larger Than the Entire Universe: Selected Poems, tr. Richard Zenith, Penguin Classics, 2006.

- A Centenary Pessoa, tr. Keith Bosley & L. C. Taylor, foreword by Octavio Paz, Carcanet Press, 2006.

- Philosophical Essays: A Critical Edition. Edited with notes and introduction by Nuno Ribeiro. New York: Contra Mundum Press, 2012.

- The Transformation Book — or Book of Tasks. Edited with notes and introduction by Nuno Ribeiro and Cláudia Souza. New York: Contra Mundum Press, 2014.

- The Complete Works of Alberto Caeiro. Edited by Jerónimo Pizarro and Patricio Ferrari, translated by Margaret Jull Costa and Patricio Ferrari. New Directions, 2020.

- The Complete Works of Álvaro de Campos, translated by Patricio Ferrari and Margaret Jull Costa. New Directions, 2023.

See Also

In Spanish: Fernando Pessoa para niños

In Spanish: Fernando Pessoa para niños

- Geração de Orpheu

- Heteronym

- Álvaro de Campos

- The Book of Disquiet

- The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis

- Portuguese poetry

- Dreams of Speaking