Atlantic puffin facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Atlantic puffin |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Genus: |

Fratercula

|

| Species: |

arctica

|

|

|

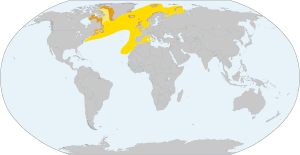

| Breeding range (orange) and winter range (yellow) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Alca arctica Linnaeus, 1758 |

|

The Atlantic puffin (Fratercula arctica), also called the common puffin, is a type of seabird in the auk family. It is the only puffin that lives in the Atlantic Ocean. Two other puffin species, the tufted puffin and the horned puffin, live in the Pacific Ocean.

Atlantic puffins breed in places like Iceland, Norway, Greenland, and parts of Canada and the United Kingdom. The largest group of puffins is found in Iceland, especially on the Westman Islands. Even though there are many puffins, their numbers have been dropping fast in some areas. Because of this, the IUCN says they are a vulnerable species.

On land, the Atlantic puffin stands upright like other auks. In the sea, it swims on the surface. It mainly eats small fish, which it catches by diving underwater. It uses its wings to help it swim fast.

This puffin has a black head and back, with light grey patches on its cheeks. Its belly is white. Its wide, colorful red and black beak and bright orange legs stand out. In winter, when it is at sea, it sheds its feathers (this is called moulting). Some of its bright face colors fade, but they return in the spring. Male and female puffins look the same, but males are usually a bit bigger. Young puffins look similar, but their cheek patches are dark grey. Their beaks are narrower and dark grey with a yellowish tip, and their legs and feet are also dark. Puffins from colder northern areas are usually larger than those from the south.

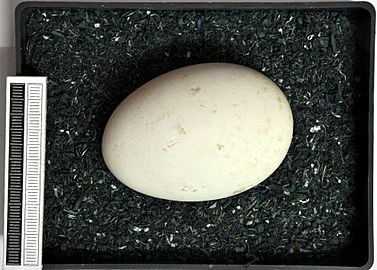

Atlantic puffins spend autumn and winter far out in the cold northern seas. They return to coastal areas in late spring to breed. They build nests in colonies on cliffs, digging burrows where they lay one white egg. The baby puffin, called a chick, mostly eats whole fish and grows quickly. After about 6 weeks, it is ready to fly (this is called fledging). It leaves the nest at night and swims away from the shore. It won't return to land for several years.

Puffin colonies are usually on islands where there are no land animals that hunt them. However, adult puffins and young chicks are still in danger from birds like gulls and skuas. Sometimes, a bird like an Arctic skua will bother a puffin carrying fish, making it drop its meal. Because of their striking looks, colorful beaks, and waddling walk, puffins are sometimes called "clowns of the sea" or "sea parrots." The Atlantic puffin is the official bird of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador.

Contents

What is an Atlantic Puffin?

The Atlantic puffin is a type of seabird that belongs to the auk family, called Alcidae. This family also includes birds like guillemots and razorbills. The Atlantic puffin is the only puffin species found in the Atlantic Ocean. Its closest relatives are the tufted puffin and the horned puffin, which live in the Pacific Ocean.

The name Fratercula comes from a Latin word meaning "friar." This is because the puffin's black and white feathers look a bit like a monk's robes. The name arctica means "northern," referring to where these birds live. The word "puffin" itself used to mean the fatty meat of a different bird, the Manx shearwater. Later, people started using it for the Atlantic puffin, probably because they both nest in similar ways. The official English name is "Atlantic puffin."

Puffins from different areas can be slightly different sizes. For example, puffins from northern Iceland are usually bigger than those from the Faroe Islands. This means that puffins in colder, northern places tend to be larger.

What Do Atlantic Puffins Look Like?

The Atlantic puffin is a strong bird with a thick neck, short wings, and a short tail. It is about 28 to 30 centimeters (11 to 12 inches) long from its beak to its tail. Its wings can spread 47 to 63 centimeters (18 to 25 inches) wide. On land, it stands about 20 centimeters (8 inches) tall. Males are usually a little bigger than females, but they have the same colors.

Their forehead, head, and back of the neck are shiny black, as are their back, wings, and tail. They have a wide black band around their neck and throat. On each side of their head, there's a large, pale grey patch. These patches almost meet at the back of the neck. Their eyes look almost triangular because of small blue-grey skin patches above and below them. Their eyes are dark brown or blue, with a red ring around them. The puffin's chest, belly, and under-tail feathers are white.

Their legs are short and set far back on their body, which makes them stand upright on land. Both their legs and large webbed feet are bright orange, with sharp black claws.

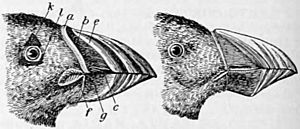

The puffin's beak is very special. From the side, it looks wide and triangular. The part near the tip is orange-red, and the part closer to the head is dark grey. A yellow line separates these two colors, and there's a yellow, wrinkled area at the base of the beak. The beak gets wider and deeper as the bird gets older. Older birds might even have grooves on the red part of their beak. Puffins have a very strong bite.

The bright orange beak and other colorful face parts grow in the spring. After the breeding season, these bright colors and extra skin pieces fall off during a partial moult. This makes the beak look less wide, less bright, and darker grey. The eye decorations also disappear, and the eyes look round. At the same time, the feathers on their head and neck are replaced, and their face becomes darker. People rarely see puffins in their winter plumage because they go out to sea after their chicks leave the nest and don't come back to land until the next breeding season.

Young puffins look like adults but are duller. They have a much darker grey face and yellowish-brown beak tip and legs. After leaving the nest, they go straight to the sea and don't return to land for several years. Each year, their beak gets wider, their face patches get lighter, and their legs and beak get brighter.

Atlantic puffins fly straight, usually about 10 meters (33 feet) above the sea. They mostly move by paddling with their webbed feet and don't fly much while at sea. They are usually quiet when at sea, making only soft purring sounds when flying. At their breeding colonies, they are quiet above ground. But inside their burrows, they make a growling sound, like a chainsaw starting up.

Where Do Atlantic Puffins Live?

The Atlantic puffin lives in the colder waters of the North Atlantic Ocean. They breed along the coasts of northwest Europe, the Arctic, and eastern North America. More than 90% of all Atlantic puffins live in Europe. Colonies in Iceland alone are home to 60% of the world's Atlantic puffins! The largest colony in the western Atlantic is in the Witless Bay Ecological Reserve in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Other big breeding spots include Norway, the Faroe Islands, the Shetland and Orkney Islands, Greenland, and Nova Scotia. Smaller groups are found in other parts of the British Isles, Russia, and Maine in the USA. Islands are very popular for breeding because they are safer from land predators.

When not breeding, puffins spread out across the North Atlantic Ocean, including the North Sea. They can even go into the Arctic Circle. In summer, they can be found as far south as northern France and Maine. In winter, they might travel as far south as the Mediterranean Sea and North Carolina. These ocean areas are huge, so it's rare to see puffins far out at sea. Scientists have attached tiny trackers to puffins' legs to learn where they go. One puffin traveled over 4,800 miles (7,700 km) in eight months!

Puffins live a long time and have only one chick each year. This means that adult puffins surviving is very important for the species. Most puffins that disappear are lost during the time they spend at sea in winter. They spread out widely in the open ocean. We don't know much about what they do or eat at sea. However, it seems that having enough food in both winter and summer helps them survive.

How Do Atlantic Puffins Behave?

Like many seabirds, Atlantic puffins spend most of the year far out in the ocean. They only come to coastal areas to breed. They are social birds and usually breed in large groups called colonies.

Life at Sea

Atlantic puffins live alone when they are out at sea. It's very hard to study them in the vast ocean. When at sea, a puffin floats like a cork, pushing itself through the water with its strong feet. It always faces the wind, even when resting or sleeping. It spends a lot of time cleaning its feathers to keep them in good condition. Its fluffy under-feathers stay dry and keep it warm. Like other seabirds, its back is black and its belly is white. This helps it hide: predators from above can't see it against the dark water, and predators from below can't see it against the bright sky.

To take off, an Atlantic puffin runs across the water, flapping its wings hard, before flying into the air. Their wings are small for their body weight because they are used for both flying and swimming underwater. To stay in the air, their wings have to beat very fast, many times per second. They fly straight and low over the water, reaching speeds of 80 kilometers (50 miles) per hour. Landing can be tricky; they might crash into a wave or do a belly flop.

While at sea, Atlantic puffins have their yearly moult. Unlike most land birds that lose a few feathers at a time, puffins lose all their main flight feathers at once. This means they can't fly for a month or two. This usually happens between January and March.

What Do They Eat?

The Atlantic puffin's diet is almost all fish. Sometimes, they also eat shrimp, other crustaceans, molluscs, and worms, especially near the coast. When fishing, they swim underwater using their partly open wings like paddles to "fly" through the water. Their feet act like a rudder. They can swim fast and dive very deep, staying underwater for up to a minute. They can eat fish up to 18 centimeters (7 inches) long, but they usually catch smaller fish, about 7 centimeters (3 inches) long. An adult puffin needs to eat about 40 small fish a day. They often eat sand eels, herring, sprats, and capelin.

Puffins hunt by sight. They can swallow small fish underwater. But they bring larger fish to the surface. They can catch several small fish in one dive. They hold the first fish in their beak with their strong, grooved tongue while catching more. Their beak is hinged in a way that allows them to hold a row of fish in place. They also have inward-pointing bumps on the edges of their beak to keep the fish from slipping. Puffins deal with extra salt from the sea by using their kidneys and special salt glands in their nostrils.

Life on Land

In the spring, adult puffins return to land, usually to the same colony where they were born. They gather for a few days on the sea before going back to their nesting spots on the cliffs. The first birds to arrive get the best spots, which are usually burrows on grassy slopes near the cliff edge, where it's easiest to take off. Puffins are usually monogamous, meaning they stay with the same partner. But this is more because they return to the same nest site each year, rather than always choosing the same mate.

Birds that arrive later might find all the good nesting spots taken. They end up nesting on the edges of the colony, where they are more at risk from predators. Younger birds might arrive even later and find no nesting spots at all. They won't breed until the next year.

Puffins are careful when they come back to the colony. They don't like to land where other puffins aren't already present. They fly around the colony several times before landing. On the ground, they spend a lot of time cleaning their feathers. They also stand by their burrow entrances and interact with other puffins. They show who's in charge by standing tall, puffing out their chest feathers, and wagging their tail. They might walk slowly in an exaggerated way, jerk their heads, or open their beaks wide. Birds that are not in charge will lower their heads, keep their bodies flat, and scurry past the dominant ones.

Puffins usually signal they are about to take off by lowering their bodies briefly. Then, they run down the slope to get enough speed. If a bird gets scared and takes off suddenly, it can cause a panic in the colony. All the birds might fly into the air and circle around. The colony is most active in the evening. Birds stand outside their burrows, rest on the grass, or walk around. Then, the slopes empty for the night as the birds fly out to sea to sleep, often choosing fishing areas so they can start hunting early.

Puffins are very good at digging and repairing their burrows. The grassy slopes can become full of tunnels. Sometimes, burrows collapse, especially if people walk carelessly over them. New colonies are unlikely to start on their own because puffins only nest where other puffins are already present. However, the Audubon Society successfully brought puffins back to Eastern Egg Rock Island in Maine after 90 years. By 2011, over 120 pairs were nesting there again.

How Do They Have Babies?

After spending the winter alone in the ocean, it's not clear if Atlantic puffins meet their partners offshore or when they return to their old nests. Once on land, they quickly start to clean and improve their burrows. Often, one puffin stands outside while the other digs, kicking out dirt and grit that showers its partner. Some puffins collect dry grass for their nests, while others don't.

Puffins are sexually mature when they are 4 to 5 years old. They nest in colonies, digging burrows on grassy clifftops or using old holes. Sometimes, they nest in cracks or among rocks. They might compete with other birds or animals for burrows. A puffin can dig its own hole or move into a burrow dug by a rabbit, and they have been known to chase away the original owner. They stay with the same partner for life and both parents help care for the chick. The male spends more time guarding the nest, while the female spends more time incubating the egg and feeding the chick.

Egg-laying begins in April in southern colonies, but not until June in Greenland. The female lays one white egg each year. If this egg is lost early in the breeding season, she might lay another. The egg is large for the size of the bird, about 61 mm (2.4 inches) long and 42 mm (1.7 inches) wide, weighing about 62 grams (2.2 ounces). Both parents share the job of keeping the egg warm (this is called incubation). They each have two bare patches on their belly that provide heat for the egg. The parent on duty in the dark nest usually sleeps, occasionally coming out to shake dust from its feathers or fly down to the sea.

The egg hatches in about 39 to 45 days. The first sign that a chick has hatched is when an adult arrives with a beak full of fish. For the first few days, the chick might be fed beak-to-beak. Later, the fish are just dropped on the nest floor for the chick to swallow whole. The chick is covered in fluffy black down, its eyes are open, and it can stand as soon as it hatches. It grows quickly, gaining about 10 grams (0.35 ounces) per day. At first, one parent stays with it, but as it gets hungrier, it is left alone more often. The chick sleeps a lot but also exercises. It moves nesting material, picks up stones, flaps its small wings, and pushes against the burrow walls. It goes to the entrance or a side tunnel to go to the bathroom. The growing chick seems to know when an adult is coming, moving closer to the entrance just before they arrive. It retreats to the nest when the adult brings fish.

Puffins often hunt for fish 100 kilometers (60 miles) or more from their nests. But when feeding their chicks, they only go about half that distance. Adults bringing fish to their chicks often arrive in groups. This helps them avoid kleptoparasitism, where birds like the Arctic skua harass puffins until they drop their fish. Arriving in groups also helps reduce attacks from the great skua.

In the Shetland Islands, sand eels are usually 90% of the food fed to chicks. In years when there weren't many sand eels, many chicks starved. In Norway, herring is the main food. When herring numbers dropped, so did puffin numbers. In Labrador, puffins were more flexible. When their usual food, capelin, was scarce, they found other types of fish for their chicks.

Chicks take 34 to 50 days to fledge, depending on how much food is available. In years with little fish, the whole colony might take longer to fledge. The normal time is 38 to 44 days, by which time chicks are about 75% of their adult weight. The chick might come to the burrow entrance to go to the bathroom, but it usually doesn't come out into the open. It seems to dislike light until it's almost ready to fledge. Even though adults bring less fish in the last few days, the chick is not abandoned. Sometimes, an adult is seen bringing food even after the chick has left. In its last few days underground, the chick loses its downy feathers, and its juvenile feathers appear. Its beak and legs are dark, and it doesn't have the white face patches of an adult.

The chick finally leaves its nest at night, when it's safest from predators. It comes out of the burrow, often for the first time, and walks, runs, and flaps its way to the sea. It can't fly properly yet, so going down a cliff is dangerous. Once it reaches the water, it paddles out to sea and might be 3 kilometers (2 miles) from shore by morning. It doesn't join other puffins and won't return to land for 2 to 3 years.

Who Hunts Atlantic Puffins?

Atlantic puffins are probably safer when they are out at sea. In the water, dangers often come from below, and puffins sometimes put their heads underwater to look for predators. Seals and large fish have been known to kill puffins. Most puffin colonies are on small islands, which helps them avoid land animals like foxes, rats, stoats, weasels, cats, and dogs. When puffins come ashore, they are still at risk, mainly from birds of prey.

Birds that hunt Atlantic puffins from the air include the great black-backed gull and the great skua. These birds can catch a puffin in flight or attack one on the ground. When puffins see danger, they take off and fly to the safety of the sea or hide in their burrows. If caught, they fight back fiercely with their beaks and sharp claws. When many puffins are flying around the cliffs, it's hard for a predator to focus on just one. But any puffin alone on the ground is in greater danger. Smaller gulls like the European herring gull usually can't take down a healthy adult puffin. However, they walk through the colony, taking any eggs that have rolled out of burrows or young chicks that have wandered too far. They also steal fish from puffins returning to feed their young. The Arctic skua is a specialized thief that bothers puffins in the air, forcing them to drop their fish, which the skua then snatches.

Puffins can also have tiny creatures living on them, like ticks and fleas.

Puffins and People

Protecting Puffins

The Atlantic puffin lives in a huge area, covering over 1.6 million square kilometers (620,000 square miles). Europe is home to over 90% of the world's puffins, with about 9.5 to 11.6 million adults. In 2015, the International Union for Conservation of Nature changed the puffin's status from "least concern" to "vulnerable." This was because their numbers were dropping quickly in Europe. In 2018, the total world population was estimated at 12 to 14 million adult birds.

Some reasons for the decline in puffin numbers include more predators like gulls and skuas, new animals like rats and cats on nesting islands, pollution, getting caught in fishing nets, less food, and climate change. On the island of Lundy in the UK, puffin numbers dropped from 3,500 pairs in 1939 to just 10 pairs in 2000. This was mainly because of rats eating their eggs and chicks. After the rats were removed, the puffin population started to recover.

Puffin numbers actually increased a lot in the late 20th century in the North Sea, including on the Isle of May and the Farne Islands. In 2013, nearly 40,000 pairs were counted on the Farne Islands. This is still much smaller than the Icelandic colonies, which have five million pairs. In the Westman Islands in Iceland, puffins were almost wiped out by too much hunting around 1900. A 30-year ban on hunting helped them recover. Now, hunting is managed to be sustainable. However, since 2000, puffin numbers have dropped sharply in Iceland, Norway, the Faroe Islands, and Greenland. A similar trend has been seen in the United Kingdom. Experts believe the European population could drop by 50–79% between 2000 and 2065.

SOS Puffin is a project in Scotland to help puffins on islands in the Firth of Forth. On Craigleith island, a large plant called tree mallow grew everywhere, stopping puffins from finding good places to nest. Volunteers have been cutting back the plants, and puffins are returning in larger numbers to breed. Another project encourages drivers to check under their cars in late summer. Young puffins, confused by street lights, sometimes land in towns and hide under vehicles.

Project Puffin started in 1973 to bring Atlantic puffins back to nesting islands in the Gulf of Maine in the USA. Eastern Egg Rock Island had puffins until 1885, when they disappeared due to overhunting. Scientists moved 10- to 14-day-old puffin chicks from Great Island in Newfoundland to Eastern Egg Rock. The young puffins were placed in artificial burrows and fed fish daily. This was done every year until 1986, with 954 young puffins moved in total. Each chick was tagged before it fledged. The first adults returned to the island by 1977. Puffin models were placed on the island to make it look like an active colony. In 1981, four pairs nested on the island. By 2014, 148 pairs were nesting there. This project showed that it's possible to bring seabirds back to nesting sites, and that using models and recordings can help.

Pollution and Climate Change

Since Atlantic puffins spend winters in the open ocean, they are at risk from things like oil spills. Oiled feathers don't keep the bird warm and make it less able to float. Many birds die, and others get sick from trying to clean the oil off. This can harm their bodies and affect their ability to have babies. Oil spills in winter might affect them less than birds closer to shore, as crude oil slicks break up in the waves. However, after a big oil spill in 1967, the number of puffins breeding in France dropped to only 16% of what it was before.

Atlantic puffins are good indicators of the health of the ocean. They eat fish, which can contain high levels of pollution like heavy metals (mercury, arsenic). Scientists can test puffin eggs, feathers, or organs to see how much pollution is in the environment.

Climate change can also affect seabirds in the northern Atlantic. Warmer sea temperatures might help some puffin colonies in the north. But breeding success depends on having enough food when chicks are growing. In northern Norway, young herring are the main food for chicks. The number of young herring depends on water temperature, which affects the tiny sea creatures they eat. So, puffin breeding success is linked to the sea temperatures of the previous year.

In Maine, warmer sea temperatures are causing fish populations to shift. This means there aren't enough herring, which are the main food for puffins there. Some adult puffins have become very thin and died. Others have brought large butterfish to the nest, but these are often too big for the chicks to swallow, causing them to starve. Maine is at the southern edge of the puffin's breeding range, and with changing weather, their breeding area might move further north.

Puffins and Tourism

Atlantic puffin breeding colonies are a great sight for bird watchers and tourists. For example, 4,000 puffins nest each year on islands off the coast of Maine. Visitors can see them from tour boats in the summer. The Project Puffin Visitor Center in Rockland provides information about the birds and conservation efforts. You can even watch the colony on Seal Island National Wildlife Refuge through live cameras during breeding season. Similar tours are available in Iceland, the Hebrides, and Newfoundland.

Hunting Puffins

In the past, Atlantic puffins were caught and eaten fresh, salted, or smoked. Their feathers were used for bedding, and their eggs were eaten, though they were harder to get from the nests than other seabird eggs. Today, in most countries, Atlantic puffins are protected by law. In countries where hunting is still allowed, strict rules prevent too many from being caught. Even though some people have called for a complete ban on hunting puffins in Iceland due to concerns about fewer chicks surviving, they are still caught and eaten there and on the Faroe Islands.

Puffins in Culture

The Atlantic puffin is the official bird symbol of the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. It has also been proposed as a symbol for a political party in Canada. The Norwegian town of Værøy has an Atlantic puffin as its town symbol. Puffins have many nicknames, like "clowns of the sea" and "sea parrots." Young puffins are sometimes called "pufflings."

Several islands have been named after the bird. The island of Lundy in the United Kingdom might get its name from the Norse words lund-ey, meaning "puffin island." Lundy even issued its own coins and stamps with "puffins" as the currency. Many other countries and places have featured Atlantic puffins on their stamps. A French bird protection charity uses a pair of Atlantic puffins as its symbol.

The publisher Penguin Books started a line of children's books called Puffin Books in 1939. These books were very popular, and Puffin Book Clubs were started in schools to encourage reading. There was even a children's magazine called Puffin Post.

On the Icelandic island of Heimaey, there's a tradition where children rescue young puffins. These pufflings sometimes get confused by street lights when they leave their nests and land in the village. The children collect them and release them safely into the sea. This tradition is featured in the children's book Nights of the Pufflings.

Images for kids

-

Puffin Island, County Kerry, Ireland, a dedicated puffin conservation area

-

Outside burrow on Skomer Island

See also

In Spanish: Frailecillo atlántico para niños

In Spanish: Frailecillo atlántico para niños