Fresco facts for kids

Fresco is a special way of painting pictures directly onto walls. A true fresco is painted onto plaster that is still wet and fresh. The word fresco comes from Italian, meaning "fresh." This method makes the paint become part of the wall itself.

Contents

Why Artists Love and Hate Frescoes

The Good Side of Fresco Painting

Fresco painting is great for walls. It's easier to spread paint on fresh, damp plaster than on dry plaster. When paint goes onto dry plaster, it just soaks right in.

Another good thing is how the paint mixes with the plaster. This means the colors won't rub off easily. Frescoes can last for hundreds of years. If they are kept clean and dry, their colors stay bright for a very long time.

Fresco is also a "green" way to paint. It doesn't use harmful chemicals. The water, a material called calcite, and the colors don't cause pollution.

The Challenges of Fresco Painting

The main challenges with frescoes come from the plaster itself. It must be mixed fresh every day. Then it needs to be put on the wall and allowed to dry a little.

As the plaster starts to dry, or "set," the artist can begin painting. The artist must work very quickly and carefully. If a mistake is made, the wet plaster has to be scraped off.

While the plaster sets, it can get hot and release gases. This can make working on a fresco uncomfortable. Also, frescoes are painted on walls or ceilings. This means they cannot be moved or rearranged like other paintings.

How Artists Create Frescoes

Artists plan their fresco work very carefully. They start with a small drawing of the picture. Then, they make a large drawing called a cartoon. This helps them figure out the best order to paint the picture. A big fresco might take more than a week to finish. Each day's work is called a giornata, which means "day" in Italian.

When a day's work begins, the artist needs to be fast. So, there is usually an assistant who mixes the plaster and helps.

The artist pins up the drawing. They use a sharp tool to mark the lines of the drawing onto the wet plaster. Then, they paint the outlines of the picture. Being accurate is very important. The artist needs to get it right on the first try.

As the painting dries, the artist goes over the whole giornata again. They add small details to faces and clothing. They also paint shadows to make the picture look more real.

At the start of the next day, the edge of the last giornata is scraped. This helps the new plaster join smoothly. Often, you can see these joins. They show how many days it took to create the painting.

A Journey Through Fresco History

Ancient Frescoes: Art from Long Ago

Not all old wall paintings are true frescoes. For example, many wall paintings in Ancient Egypt were done on dry plaster. So, they are not true frescoes.

The Royal Palace at Knossos in Crete, around 1500 BC, had many frescoes. A famous one shows athletes dancing with a bull.

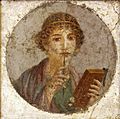

Many Ancient Roman wall paintings can be seen at Pompeii from the 1st century AD. However, these are also not true frescoes.

The Sigiriya Frescoes in Sri Lanka, painted around 485 AD, use a method called "fresco lustro." This is a bit different from pure fresco. It includes a mild binding material. This makes the frescoes extra strong. They have lasted for nearly 1500 years, even though they were exposed to the weather.

Medieval Frescoes: Stories on Church Walls

Many frescoes come from the late Middle Ages, from about 1000 to 1400 AD. During this time, it was popular to paint the inside of churches. Artists painted people and stories from the Bible. The artists and priests carefully planned the order of the pictures.

Above the altar, you often see a picture of Jesus. On the west wall, there is often a powerful picture of The Last Judgement. This was meant to remind people to follow Jesus. Many frescoes like these can be found in Greece, Spain, Portugal, Serbia, Armenia, Romania, and Russia. A few are in Germany, France, and Italy.

Renaissance Frescoes: A New Era of Art

In Italy, around 1300 AD, the artist Giotto painted frescoes that were incredibly lifelike. People were amazed by them. Each picture felt like looking at a stage where real people were telling a story. This was the start of a period in art history called the Renaissance. Giotto's frescoes became very famous. He had many students and followers.

Giotto's most famous frescoes are in the Arena Chapel in Padua. He also painted in the Church of St. Francis at Assisi and at Santa Croce (Church of the Holy Cross) in Florence.

A hundred years later, around 1400 AD, two artists named Masolino and Masaccio worked in Florence. They painted a chapel together. Their names mean "Little Tom" and "Fat Tom." Masaccio's painting style brought the biggest change since Giotto. His two crying, naked figures of Adam and Eve were especially impactful. Everyone thought Masaccio was one of the greatest painters. But he died at only 27 years old. These frescoes are in the Church of the Carmine, in Florence.

In the 1400s, many other Italian artists were hired to paint churches or chapels. They were paid by patrons, who were rich people who could afford to support artists. The most important patron was the Pope. Pope Sixtus IV had built a new chapel in the Vatican in Rome. In 1481, he asked some of Italy's best artists to decorate the walls. You can read more about this at Sistine Chapel.

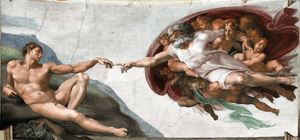

In 1508, work continued in the Sistine Chapel. Pope Julius II asked the great artist Michelangelo to come to Rome and paint the ceiling. It took Michelangelo four years. He even got sick from the hard work and the smell. But when he finished, he had created one of the greatest artworks in the world. Then, from 1537 to 1541, he painted the west wall of the same chapel with The Last Judgement.

For the next 200 years, painted ceilings were very popular. But artists soon found it easier to paint with oil on canvas and then attach it to the ceiling. This was simpler than painting directly onto the ceiling using fresco. Because of this, the popularity of fresco painting slowly began to fade.

More Amazing Fresco Art

-

Etruscan fresco. Detail of two dancers from the Tomb of the Triclinium in the Necropolis of Monterozzi 470 BC, Tarquinia, Lazio, Italy

-

A Roman fresco of a young man from the Villa di Arianna, Stabiae, 1st century AD.

-

Fresco by Giotto, Scrovegni Chapel in Padua. Sky and blue mantle of Maria were painted a secco, and large part of the painting is now lost

-

The first known Egyptian fresco, Tomb 100, Hierakonpolis, Naqada II culture (c. 3500–3200 BCE)

-

The Fisherman, Minoan Bronze Age fresco from Akrotiri, on the Aegean island of Santorini (classically Thera), dated to the Neo-Palatial period (c. 1640–1600 BC). The settlement of Akrotiri was buried in volcanic ash (dated by radiocarbon dating to c. 1627 BC) by the Minoan eruption on the island, which preserved many Minoan frescoes like this

-

Etruscan fresco of Velia Velcha from the Tomb of Orcus, Tarquinia

-

View of a woman's face in the central chamber of the Ostrusha mound built in the 4th century BC in Bulgaria

-

Frescos in the Monastery of Saint Moses the Abyssinian, Syria

-

Interior view with the frescoes dating back to 1259, Boyana Church in Sofia, UNESCO World Heritage List landmark.

-

Pantocrator from Sant Climent de Taüll, in MNAC Barcelona

-

Myrrhbearers on Christ's Grave, c 1235 AD, Mileševa monastery in Serbian

-

Fernando Leal, Miracles of the Virgin of Guadalupe, Fresco Mexico City

-

The 18th-century BC fresco of the Investiture of Zimrilim discovered at the Royal Palace of ancient Mari in Syria

-

Dante in Domenico di Michelino's Divine Comedy in Duomo of Florence

-

Frescoes from the Byzantine and two distinct Bulgarian Periods under the Dome of the Church of St. George, Sofia

See also

In Spanish: Fresco para niños

In Spanish: Fresco para niños