George Washington Julian facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

George Julian

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Indiana |

|

| In office March 4, 1849 – March 3, 1851 |

|

| Preceded by | Caleb Blood Smith |

| Succeeded by | Samuel W. Parker |

| Constituency | 4th district |

| In office March 4, 1861 – March 3, 1871 |

|

| Preceded by | David Kilgore |

| Succeeded by | Jeremiah M. Wilson |

| Constituency | 5th district (1861–69) 4th district (1869–71) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 5, 1817 Centerville, Indiana, U.S. |

| Died | July 7, 1899 (aged 82) Irvington, Indiana, U.S. |

| Political party | Whig (Before 1848) Free Soil (1848–1855) Republican (1855–1872) Liberal Republican (1872–1873) Democratic (1873–1899) |

| Spouses | Anne Finch (1845–1860) Laura Giddings (1863–1884) |

| Children | 5 |

| Signature | |

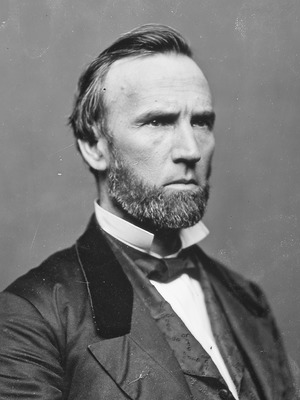

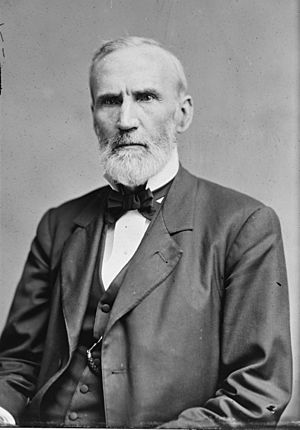

George Washington Julian (born May 5, 1817 – died July 7, 1899) was an American politician, lawyer, and writer from Indiana. He served in the United States House of Representatives during the 1800s.

Julian was a strong opponent of slavery. He was the Free Soil Party's choice for vice president in the 1852 election. During the American Civil War and the Reconstruction era, he was a key leader among the Radical Republicans.

Born in Wayne County, Indiana, Julian became a lawyer in Centerville, Indiana. He was first elected to the Indiana House of Representatives as a member of the Whig Party. He then helped create the anti-slavery Free Soil Party. He won election to the U.S. House of Representatives, but did not win a second term right away.

While in Congress, Julian strongly supported land reform, like the Homestead Acts. After leaving Congress, he ran for vice president in 1852. His ticket received nearly 5% of the popular vote.

After the Kansas–Nebraska Act was passed, Julian became a leader of Indiana's new Republican Party. He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives again in 1860. He helped pass the 1862 Homestead Act and pushed for the end of slavery. He supported President Abraham Lincoln but also disagreed with some of Lincoln's wartime plans. He preferred the Wade–Davis Bill for Reconstruction over Lincoln's ideas.

Julian voted for the Thirteenth Amendment, which ended slavery in the U.S. After the war, he criticized President Andrew Johnson and called for his impeachment. In 1868, Julian proposed a constitutional amendment for women's suffrage, giving women the right to vote.

He lost his re-election bid in 1870 and went back to practicing law. Julian opposed President Ulysses S. Grant's government and became a leader of the Liberal Republicans. After Grant won the 1872 election, Julian joined the Democratic Party. In 1885, President Grover Cleveland appointed him surveyor general of the New Mexico Territory. Julian was the father-in-law of Joshua Reed Giddings and the father of Grace Julian Clarke, a leader for women's voting rights.

Contents

Early Life and Education

George Washington Julian was born on May 5, 1817. His birthplace was near Centerville, Indiana, in Wayne County, Indiana. His parents, Isaac and Rebecca Julian, were Quakers. They had moved to Indiana from North Carolina. George's father, Isaac, died when George was only six years old. This left Rebecca to raise their six children.

Julian went to a regular school and loved to read. When he was eighteen, he briefly worked as a schoolteacher. However, he soon decided teaching was not for him. In 1839, a friend suggested he become a lawyer. Julian studied law in the office of attorney John S. Newman in Centerville. He became a lawyer in Indiana in 1840. He first opened a law practice in Greenfield, Indiana. Later, he moved back to Centerville to work with his older brother, Jacob, as a law partner.

Family and Marriages

Julian married Anne Elizabeth Finch in May 1845. This was the same year he was elected to the Indiana General Assembly. They had three children: Edward, Louis, and Frederick. Sadly, Edward and Louis died when they were young. Anne passed away from tuberculosis on November 15, 1860, at age thirty-four. Their son Frederick became an actor and died in 1911.

On December 31, 1863, Julian married Laura Giddings. Laura was the daughter of Joshua Reed Giddings, a U.S. congressman from Ohio. Joshua Giddings was also a strong opponent of slavery. Julian and Laura had two children, Grace and Paul. Laura died in 1885. Paul became a civil engineer and died in 1929.

Grace Julian Clarke became a well-known clubwoman and a leader for women's suffrage in Indianapolis. She helped start the Women's Franchise League of Indiana. Grace stayed very close to her father, even after marrying Charles B. Clarke. Charles was an attorney and served in the Indiana Senate. Grace was a talented writer and published several books. She also wrote newspaper columns for the Indianapolis Star from 1911 to 1929. Her articles helped shape public opinion on women's voting rights. Grace died in 1938.

Political Career

George Julian was a member of five different political parties during his career. He served in the Indiana General Assembly as a Whig. He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives five times. One term was as a member of the Free Soil Party, and four terms were as a Republican.

He was also the Free Soil Party's candidate for U.S. vice president in the 1852 election. However, Julian and the presidential candidate, John P. Hale, lost without winning any electoral votes. In 1872, Julian joined the Liberal Republicans. By 1884, he became a member of the Democratic Party.

Julian is most famous for his strong opposition to slavery. He also supported land reform and women's right to vote. When people criticized him for changing parties, Julian argued that the parties changed their views, especially on slavery, while his own beliefs stayed the same.

Early Political Steps as a Whig

Julian began his political career in 1845. He was elected to the Indiana House of Representatives as a Whig from Centerville. He voted for a bill about the state's large debts from its internal improvement projects. This vote, however, cost him the Whig Party's support. He did not get the Whig nomination for the Indiana Senate in 1847.

Around this time, Julian, who was raised a Quaker, started to change his religious beliefs to Unitarianism. He also became very active in Indiana's antislavery movement.

Joining the Free Soil Party

Julian helped create the Free Soil Party. He was a delegate at the party's convention in Buffalo, New York, in 1848. In December, he announced he would run for Congress. He won election as a Free Soil candidate to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1849.

Julian's election happened because of a partnership with the Democratic Party in Indiana's Fourth Congressional District. This area was known for its strong anti-slavery views, partly due to a large Quaker population. Julian's economic ideas were closer to the Democrats' views than the Whigs'. He did not support high protective tariffs or a new national bank. With Democratic support, Julian won election to the Thirty-first Congress in 1849. He was part of a small group of about twelve Free Soilers and other members.

Julian's interest in land reform began in the 1840s and lasted his whole life. He believed families should work their own farms without slave labor. He was concerned about U.S. land policies. On January 29, 1851, he gave his first House speech supporting Andrew Johnson's homestead bill. However, Congress did not approve this law.

By 1851, when Julian ran for re-election, political conditions in Indiana had changed. The state's Democratic Party became more against any limits on slavery in new territories. They supported the Compromise of 1850 and the Fugitive Slave Law. Also, a new state constitution was written. It included a rule that stopped black people from moving into the state. (This rule was removed in 1881.) Because of these changes, the Free Soil and Democratic partnership that elected Julian faced problems. Julian lost his re-election to Samuel W. Parker, a Whig.

In the 1852 presidential election, the Free Soilers (who called themselves the Free Democracy Party) chose John P. Hale for president. They needed someone from the Midwest to balance the ticket. Even though Julian was not at the convention, the party nominated him for vice-presidency. Hale and Julian did not win any electoral votes. They lost the election to Franklin Pierce and William R. King. Julian also lost a bid for Congress in 1854. This was when the Kansas–Nebraska Act brought back the debate over slavery. Julian then joined the People's Party, which later became the Republican Party in Indiana. He became a leader of its anti-slavery group.

Becoming a Republican Leader

In 1856, Julian was a delegate at the Republican convention in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. There, the Republican Party chose John C. Frémont as their candidate for President. Julian led the committee on national organization. In 1860, he was elected as a Republican to the Thirty-seventh Congress. He won re-election four more times, serving from 1861 to 1871.

Julian was one of the most radical Republicans in the U.S. House. He was a strong abolitionist, meaning he wanted to end slavery. He also supported civil rights, women's right to vote, and land reform. In 1861, he was appointed to the congressional Committee on Public Lands. He served as its chairman from 1863 to 1871.

During the American Civil War, Julian called for black people to be armed and join the Union army. In 1864, he tried to repeal the Fugitive Slave Law, but it was not passed at that time. A similar bill became law two years later. Julian also argued against those who said the war should be fought strictly within constitutional limits. He believed that the Constitution should not protect those who rebelled against the country.

As a member of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, Julian investigated military and civilian actions. This committee made recommendations for how the war should be fought. It also helped radical Republicans push their policies on the Abraham Lincoln administration. Julian investigated Confederate actions and the mistreatment of prisoners. He also pushed for the removal of Union Army general George B. McClellan, whom Julian saw as too slow in fighting the enemy.

Julian played a key role in passing the Homestead Act in 1862. He saw this law as a great victory for freedom and free labor over slave power. When he found that the law had loopholes that helped land speculators, he introduced ways to fix them. Julian also strongly criticized railroad land grants. He opposed the Morrill Act of 1862, which gave federal money to create agricultural and mechanical colleges.

Julian did not dislike Lincoln personally, but he disagreed with some of the president's policies, which were more moderate than his own. Julian was among the radical Republicans who worried that Lincoln would not issue the final Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. Julian later wrote that Lincoln had to yield to the widespread demand for such an order.

Julian also supported taking property from those who rebelled against the United States. He joined other radicals in voting for the Second Confiscation Act in 1862. Julian wanted the seized land to be divided into free homesteads. These would be given to Union soldiers or others who helped the Union during the war. Black laborers would also be able to get these free homesteads. Julian wanted these confiscations to be permanent, but Lincoln preferred to limit how long they would last. Julian introduced a bill in 1864 to create homesteads on confiscated lands in the South. It passed the House, but the U.S. Attorney General James Speed stopped the confiscations before the Senate could vote on the bill.

Julian initially supported a radical Republican challenge to Lincoln's re-election in 1864. He briefly joined the campaign to nominate U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase. However, he later supported Lincoln in the 1864 presidential election. Julian disagreed with Lincoln's Reconstruction policy. He preferred the plans in the Wade–Davis Bill of 1864. He also strongly advocated for giving former slaves the right to vote.

In January 1865, Julian voted for the Thirteenth Amendment to end slavery in the United States. He was very proud of his role in this. Julian compared those who voted for the Amendment to the signers of the Declaration of Independence. He wrote that the vote was the greatest event of the century. He described the cheering and joy in the hall when the measure passed. He felt like he was in a new country and could breathe better.

Unlike many other radical Republicans, Julian wanted former Confederates punished for their rebellion. He called for the execution of Jefferson Davis. He also suggested that the estates of former Confederate leaders should be taken. These lands, he said, should be given to poor people, both white and black, in the South, including Union soldiers.

Julian was a tall man with broad shoulders. He was known for being unwilling to compromise with more moderate colleagues. While campaigning for re-election in 1865, Julian had a serious disagreement with his opponent, Brigadier General Solomon Meredith. Meredith was a former commander in the Union Army. This dispute became known as the "Julian and Meredith Difficulty" in newspapers.

In 1866, a reporter described Julian's "worn, scarred, seamed and earnest face." The reporter noted that Julian's face was "grim and belligerent." An 1868 newspaper described Julian as a very impressive figure. It said he "towers above the people like a mountain." The paper noted that people always knew what George Washington Julian would do in any national crisis.

Julian was one of the first to call for President Andrew Johnson's impeachment. He was appointed to a seven-person House committee to draft impeachment articles against the president. However, the U.S. Senate did not pass the final impeachment article. This allowed Johnson to finish his term in office. Later, Julian thought the impeachment movement was an act of "party madness." In his memoirs, Julian downplayed his role in recommending Johnson's impeachment.

While Julian's main political goal in the 1850s and 1860s was to end slavery, he also supported women's right to vote for a long time. Julian had supported women's suffrage as early as 1847. He explained that he first learned about it from a book by Harriet Martineau in 1847. He found her arguments for women's right to vote very convincing. In 1853, Julian invited early women's suffrage advocates, Frances Dana Barker Gage and Emma R. Coe, to speak in his hometown. Julian was also good friends with Lucretia Mott, who helped organize the Seneca Falls Convention. After the Civil War, Julian returned to the issue of women's rights. In 1868, he proposed a constitutional amendment for women's suffrage, but it was defeated.

A Republican newspaper in Ohio once complained that Julian "uses vinegar when he might scatter sugar." The report also noted that he had a difficult personality and little patience for his opponents. It said that those who crossed him found his "unfortunate temper and his determination to fight to the bitter end." Among Julian's many political opponents was Oliver P. Morton, the powerful Republican governor of Indiana. Morton's views on how to treat former Confederates were similar to Julian's. However, Morton was slow to support black suffrage. As late as 1865, Morton argued that southern black people were not ready to vote. While Julian quickly broke with Johnson, Morton continued to support Johnson into early 1866.

In 1867, Morton redrew Julian's district boundaries. He replaced some of its most radical counties with pro-Democratic ones. This made Julian's re-election campaign in 1868 very difficult. He barely won, with accusations of voting fraud in Richmond, Indiana.

In 1869, Congress passed the Fifteenth Amendment, giving black men the right to vote. Julian felt that the fight against slavery had been won. In his bid for re-election to Congress in 1870, Julian faced a strong conservative opponent, Judge Jeremiah M. Wilson. Julian lost in the Republican primary and withdrew from the race. He supported the Republicans in the general election, but his endorsement came late, and he did not actively campaign.

Joining the Liberal Republicans

In 1872, two years after losing his re-election primary, Julian joined the Liberal Republicans. He became one of their leaders. Julian and other Republicans were unhappy with the corruption in Ulysses S. Grant's administration. At the Liberal Republican convention in Cincinnati, Ohio, on May 1, 1872, Horace Greeley was nominated for president. Julian was considered for the vice presidential nomination. However, Benjamin Gratz Brown became the party's vice presidential nominee. Julian supported Greeley in the 1872 presidential election. He received five electoral votes for vice-presidency. However, Grant won the presidential election.

After Grant's re-election, Julian left Washington, D.C. He returned to Centerville. In 1873, he and his family moved to Irvington, a community near downtown Indianapolis. He remained active in politics and continued to practice law there.

Becoming a Democrat

When the Liberal Republicans rejoined the Republicans, Julian did not follow them. Instead, he supported the Democrats. Julian agreed with Democratic views on tariffs, money issues, and fighting against railroads, land speculators, and monopolies. He also opposed the misuse of political power. He supported the Democratic ticket in 1877.

Julian officially became a member of the Democratic Party in 1884. He continued to support women's right to vote, temperance (limiting alcohol), and land reform. In 1885, President Grover Cleveland appointed Julian surveyor general of New Mexico. Julian served in this role from July 1885 until September 1889.

Later Years and Legacy

Unlike many older radical politicians, Julian did well in his later years. His work on the federal lands committee in the U.S. House made him a sought-after legal advisor for land cases. This earned him a good income.

In his later years, Julian lived in the Irvington community of Indianapolis. He remained active in politics and focused on writing. Julian wrote several books about the political scene of his time. He also wrote a biography of his father-in-law, Joshua R. Giddings. His memoir, Political Recollections (1884), was based partly on his diaries. His recollections are known for being honest, and he sometimes admitted his own mistakes. The memoirs mostly show Julian's strong principles and his belief that his positions were right.

Julian died on July 7, 1899, in Irvington. He is buried at Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis.

While representing Indiana in Congress, Julian was known for his strong character. He was a key figure in the anti-slavery movement during the Civil War and Reconstruction. His interests in land reform and women's suffrage are less known. An obituary published after his death described him as a "doctrinaire rather than a statesman." It remembered him as a "powerful champion" of the causes he supported. Julian was also described as "impatient," "arrogant," and "self-righteous," but also hardworking and steadfast in his beliefs.

Indianapolis Public School Number 57 was named in Julian's honor.

Published Works

- The Rebellion, The Mistakes of the Past, The Duty of the Present (1863)

- Homesteads for Soldiers on the Lands of Rebels (1864)

- Sale of Mineral Lands (1865)

- Radicalism and Conservation––The Truth of History Vindicated (1865)

- The Rights of Pre-emptors on the Public Lands of the Government Threatened, The Conspiracy Exposed (1866)

- Suffrage in the District of Columbia (1866)

- Regeneration before Reconstruction (1867)

- Biology versus Theology. The Bible: irreconcilable with Science, Experience, and even its own statements (1871)

- Speeches on Political Questions (1872)

- Political Recollections, 1840 to 1872 (1884)

- The Rank of Charles Osborn as an Anti-slavery Pioneer (1891)

- The Life of Joshua R. Giddings (1892)

Julian's daughter, Grace Julian Clarke, collected and published a book of his speeches. It was called Later Speeches on Political Questions: With Select Controversial Papers (1889). She also wrote George W. Julian: Some Impressions (1902), which shared her memories of him. Her biography, George W. Julian (1923), was the first book in the Indiana Historical Commission's Indiana biography series.