Geyser facts for kids

A geyser is a special kind of hot spring that shoots out water and steam. These amazing natural fountains erupt when a lot of pressure builds up underground. Many geysers erupt at regular times, like a clock. There are about 1,000 geysers worldwide. About half of them are found in Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming, United States.

Contents

How Geysers Form and Erupt

Geysers need very special conditions deep inside the Earth. Only a few places on our planet have these conditions, which is why geysers are quite rare. One famous place is Yellowstone National Park, which is actually the remains of a huge volcano. Another is Iceland, which sits on top of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, where new Earth's crust is always forming.

Geysers are often found near active volcanoes. This is because the heat for a geyser comes from hot, melted rock called magma. Surface water, like rain or snowmelt, seeps deep into the ground, sometimes as far as 2,000 meters (about 6,500 feet). There, it meets very hot rocks. The water gets super hot, but the pressure from the ground above stops it from boiling right away.

When the water gets hot enough and the pressure builds up, it suddenly turns into steam. This steam and hot water then burst out of the ground through cracks, creating a geyser eruption!

What a Geyser Needs

Even though individual geysers don't last forever, the areas where they form can last for thousands of years. The oldest known geysers are only a few thousand years old. Geysers usually form near volcanoes because they need three main things:

- Lots of Heat: A geyser needs a huge amount of heat. This heat comes from magma that is close to the Earth's surface. Geysers need much more heat than you would normally find underground. That's why they are often found in volcanic areas.

- Water: The water that shoots out of a geyser travels deep underground. It moves through cracks in the Earth's crust where there is a lot of pressure.

- A "Plumbing" System: For the heated water to erupt, it needs a special "plumbing" system. This system holds the water while it heats up. It's made of many cracks, fissures, spaces, and sometimes even underground holes.

The most important part is that the water at the bottom of this plumbing system gets hot enough to start boiling. When steam bubbles form, they rise and burst through the geyser's opening. Some water splashes out, which makes the weight of the water column lighter. This reduces the pressure on the water below. When the pressure drops, the super-hot water quickly turns into steam and boils violently, causing the geyser to erupt!

How People Use Geysers

Geysers are not just amazing to look at; they can also be very useful! People use them for different things, like making electricity, heating buildings, and attracting tourism. Many places around the world have geothermal energy, which comes from the Earth's heat.

The geyser fields in Iceland are some of the best places to use this natural heat. Since the 1920s, hot water from geysers has been used to heat greenhouses. This allows people to grow food that would normally not survive in Iceland's cold climate. Since 1943, steam and hot water from geysers have also been used to heat homes in Iceland.

Geysers in Space

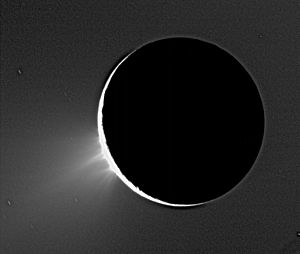

Scientists have seen jet-like eruptions on other planets and moons in our Solar System. These are often called "geysers" or "cryogeysers." But unlike Earth's geysers, these are eruptions of gas, dust, or ice particles, not liquid water.

For example, jets of water vapor have been seen near the south pole of Saturn's moon Enceladus. Eruptions of Nitrogen gas have been spotted on Neptune's moon Triton. Scientists have also seen Carbon dioxide eruptions from the southern ice cap of Mars.

Major Geyser Locations

Geysers are quite rare because they need a special mix of water, heat, and a good "plumbing" system underground. This combination is found in only a few places on Earth.

Yellowstone National Park, USA

Yellowstone National Park is the biggest geyser area in the world. It has thousands of hot springs and about 300 to 500 geysers. This means it's home to half of all the geysers on Earth! Yellowstone is mostly in Wyoming, USA, with small parts in Montana and Idaho. It also has the world's tallest active geyser, Steamboat Geyser, located in the Norris Geyser Basin.

Valley of Geysers, Russia

The Valley of Geysers (which means "Долина гейзеров" in Russian) is in the Kamchatka Peninsula of Russia. It has the second-largest number of geysers in the world. A scientist named Tatyana Ustinova discovered and explored this area in 1941. There are about 200 geysers here, along with many hot springs. The area was formed by strong volcanic activity. Many of these geysers erupt at an angle, which is quite unique.

In 2007, a huge mudflow covered two-thirds of the valley. A thermal lake started to form over the valley. Luckily, the water later went down, showing some of the buried geysers again. Velikan Geyser, one of the largest in the area, was not buried and is still active today.

El Tatio, Chile

The name "El Tatio" comes from a word in the Quechua language meaning "oven." El Tatio is located high in the Andes mountains in Chile, South America. It's about 4,200 meters (13,780 feet) above sea level and is surrounded by many active volcanoes.

This valley has about 80 geysers. It became the largest geyser field in the Southern Hemisphere after many geysers in New Zealand were destroyed. It is now the third-largest geyser field in the world. The geysers here don't erupt very high; the tallest is only about 6 meters (20 feet). However, their steam columns can reach over 20 meters (65 feet) high! The average geyser eruption at El Tatio is about 750 millimeters (2.5 feet) tall.

Taupō Volcanic Zone, New Zealand

The Taupō Volcanic Zone is on New Zealand's North Island. It is about 350 kilometers (217 miles) long and 50 kilometers (31 miles) wide. It sits over a subduction zone, where one part of the Earth's crust slides under another. Mount Ruapehu is at its southwestern end.

Many geysers in this zone were destroyed because of geothermal power plants and a dam that created a lake. However, several dozen geysers still exist. In the early 1900s, the largest geyser ever known, the Waimangu Geyser, was in this zone. It started erupting in 1900 and erupted for four years until a landslide changed the water underground. Waimangu's eruptions usually reached 160 meters (525 feet), and some huge bursts reached 500 meters (1,640 feet)! Scientists now think that the Earth's crust under this zone might be as thin as 5 kilometers (3 miles). Below that, there's a layer of magma that is 50 kilometers (31 miles) wide and 160 kilometers (99 miles) long.

Iceland

Iceland has a lot of volcanic activity, so it's home to some of the world's most famous geysers. There are about 20 to 29 active geysers in the country, plus many others that used to be active. Icelandic geysers are found in a zone that stretches from the southwest to the northeast. This zone is along the boundary between the Eurasian Plate and the North American Plate.

Most Icelandic geysers don't last forever. It's also common for many geysers here to become active again or even form new ones after earthquakes. But then they might become quiet or stop erupting after a few years or decades.

Two of Iceland's most well-known geysers are in Haukadalur. The Great Geysir, which first erupted in the 1300s, is where the word geyser comes from! By 1896, Geysir was almost quiet, but an earthquake that year made it start erupting again several times a day. However, by 1916, the eruptions mostly stopped. For much of the 1900s, it only erupted sometimes, usually after earthquakes. People even used to add soap to the spring to make it erupt for special events. Earthquakes in 2000 made the giant geyser active again for a while, but it's not erupting regularly now. The nearby Strokkur geyser erupts every 5 to 8 minutes, shooting water up to 30 meters (98 feet) high!

Geysers have also been found in at least a dozen other areas on the island. Some old geyser sites have become historical farms, which have used the hot water since medieval times.

Geyser Fields That Are No Longer Active

There used to be two large geyser fields in Nevada, USA: Beowawe and Steamboat Springs. Sadly, they were destroyed when geothermal power plants were built nearby. The drilling for these plants reduced the heat and lowered the water underground so much that the geysers could no longer erupt.

Many of New Zealand's geysers have also been destroyed by humans in the last century. Several others have stopped erupting naturally. The main remaining field is Whakarewarewa at Rotorua. Two-thirds of the geysers at Orakei Korako were flooded when the Ohakuri dam was built in 1961. The Wairakei field was lost to a geothermal power plant in 1958. The Rotomahana field was destroyed by the 1886 eruption of Mount Tarawera.

Images for kids

-

Tiny living things called hyperthermophiles create the bright colors of Grand Prismatic Spring, Yellowstone National Park

See also

In Spanish: Géiser para niños

In Spanish: Géiser para niños

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |