History of Colchester facts for kids

Colchester is a historic city in Essex, England. It was once the first capital of the United Kingdom and is known as the oldest recorded town in Britain. Vikings attacked it in the 800s and 900s. It was also a very important place for making and trading cloth in the Middle Ages.

Contents

Ancient Times

The hill where Colchester stands was shaped by an ancient river. Very old flint tools, like handaxes, have been found here. These tools were made by early hunter-gatherers. Archaeologists have also found many pieces of pottery from the Stone Age, Bronze Age, and early Iron Age.

Around Colchester, there are ancient monuments built before the town existed. These include a Stone Age henge and large Bronze Age burial mounds called barrows. Some barrows can still be seen near the University of Essex.

Iron Age Fortress and Roman City

Iron Age Camulodunon

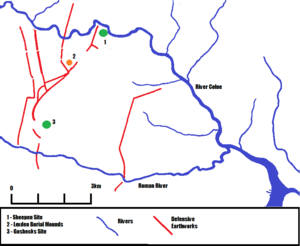

The Celtic fortress of "Camulodunon" means Stronghold of Camulos, a Celtic god. It's first mentioned on coins from around 20-10 BC. This fortress had many earthwork defenses, like ditches and banks, built from the 1st century BC onwards. These were some of the biggest defenses of their kind in Britain.

The settlement was protected by rivers on three sides. The earthworks mostly closed off the western side. Important areas inside these defenses included Gosbecks farm, a large settlement with a religious site, and Sheepen, a river port and industrial area.

Originally, Camulodunon was a stronghold of the Trinovantes tribe. Later, the Catuvellauni tribe took control. The Roman writer Strabo said that Britain traded a lot with Rome, selling things like grain, gold, iron, and slaves. Iron bars and slave chains found at Sheepen show this trade.

The Catuvellauni king, Cunobelinus, ruled from Camulodunon. He controlled a large part of southern Britain and was called "King of the Britons" by the Romans. Under him, Camulodunon became the most important place in Britain before the Romans arrived.

Around 40 AD, Cunobelinus had a disagreement with his son, Adminius, who went to Rome for help. After Cunobelinus died, his sons, Togodumnus and Caratacus, took over. They started expanding their power. Another British king, Verica, who was a friend of Rome, asked the Emperor Claudius for help.

In 43 AD, Emperor Claudius needed a military victory. He saw Verica's request as a perfect reason to invade Britain. Aulus Plautius led four Roman legions to Britain, aiming for Camulodunon. They defeated Togodumnus. Claudius then arrived with more soldiers, including elephants, and led the attack on Camulodunon. Caratacus escaped and became a hero for resisting Rome. After this battle, many British kings surrendered to Claudius in Camulodunon.

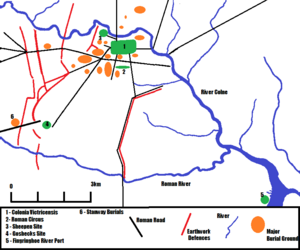

Roman Camulodunum

After the Roman invasion in 43 AD, a Roman army base, called a castrum, was built inside Camulodunon. This was the first permanent Roman army base in Britain. It was home to the Twentieth Legion. Around 49 AD, the army left, and the base was turned into a town. Many army barracks became houses.

The town's official name became Colonia Victricensis, and it was settled by retired Roman soldiers. A Roman writer named Tacitus said the town was a "strong colonia of ex-soldiers" meant to protect against rebels and teach locals about Roman law.

A huge Roman temple, the biggest classical-style temple in Britain, was built there in the 50s AD. It was dedicated to Emperor Claudius after he died. The base of this temple is now part of Colchester Castle. It's the oldest large stone Roman building you can still see in Britain.

Colchester became the capital of the Roman province of Britain. Its temple was the center of the Roman Imperial Cult (worship of the emperor). But problems grew between the Roman settlers and the local British people. In 60/61 AD, the Romans took land from the Iceni tribe after their king, Prasutagus, died. His widow, Boudica, led an uprising.

The Iceni rebels were joined by the Trinovantes, who had many complaints against the Romans in Colchester. These included Romans taking their land, forcing them to work on the Temple of Claudius, and demanding back loans. Colchester was the first target of the rebels because it was a symbol of Roman rule.

The rebels destroyed the city and killed its people. Archaeologists have found layers of ash, showing Boudica's army burned the city. After the revolt was crushed, the Roman capital moved to Londinium (London).

After being destroyed, Colchester was rebuilt even bigger. It grew to 108 acres and reached its peak in the 2nd and 3rd centuries. Its official name was Colonia Claudia Victricensis, but people still called it Camulodunum.

The city became a major industrial center. It was the only place in Britain for a while that made samian ware pottery, along with glass and metal items. Roman brick-making and wine-growing also happened nearby. Colchester had many large houses with beautiful mosaics, heating systems (hypocausts), and good water pipes.

The town had a large Roman Temple, two theaters (one was Britain's largest), several Romano-British temples, Britain's only known chariot circus, and the first town walls in Britain. It might have had a population of 30,000 people at its busiest.

In the late 3rd and 4th centuries, the Roman Empire faced problems, including raids by Saxon pirates. Forts were built along the coast to protect the town. The town walls were strengthened, and some gates were blocked.

Like many Roman towns, Colchester shrunk in size in the 4th century. However, it remained important. Many large houses were replaced by smaller ones. But between 275 and 325 AD, there was a small "building boom" with new houses and redesigned old ones. Many of the town's mosaics are from this time.

The pottery industry declined, but bone-working for furniture and jewelry increased. Glass-making also happened. Large parts of the southern town were used for farming. Public buildings became bigger and grander. The Temple of Claudius was rebuilt in the early 4th century. A large hall at Culver Street might have been a storage barn for taxes paid in grain.

An early Christian church was built outside the town walls at Butt Road. It had a cemetery with over 650 graves, some containing rare Chinese silk. This church might be one of the earliest in Britain.

Sub-Roman Town

The Roman government officially left Britain around 409–411 AD. Activity in Colchester continued at a much smaller level in the 5th century. Some burials from the 5th century have been found inside the town walls.

Coin hoards from the late 4th and early 5th centuries have also been discovered. Post-Roman and early Saxon burials from the 5th, 6th, and 7th centuries have been found outside the walls, suggesting people continued to live and bury their dead here. Archaeologists have found evidence of dwellings and pottery from this period. Some historians believe a post-Roman settlement existed here, possibly linked to the legend of Camelot.

Saxon and Viking Era

Fifth to Eighth Centuries

Archaeological evidence shows that after the Romans left, a Saxon culture became dominant in Colchester around 440–450 AD. This was a small community mainly around Head Street and High Street, which followed the old Roman roads.

During this time, London was the capital of the Kingdom of Essex. Colchester might have been an important local center for northern Essex. Evidence for Saxons includes huts, burials (some with weapons), jewelry, coins, and pottery. The Saxon river port was located at Old Heath and Blackheath.

Colchester is mentioned in old texts like the Historia Brittonum as Cair Colun. Later, it was called "Colenceaster" and "Colneceastre" in the 900s.

Ninth to Eleventh Centuries

Viking raids became very serious in 865 AD when a large Danish army invaded. In 869, the King of East Anglia was killed, and eastern England came under Danish control. Colchester became part of the Danelaw, an area ruled by Danes. Many Scandinavian place names, like Kirby and Thorpe, are found around Colchester.

The Kings of Wessex fought against the Danes. Finally, Edward the Elder's English army recaptured Colchester in 917 AD. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says that Edward's army "beset the town, and fought thereon till they took it, and slew all the people." Later that year, King Edward returned to "repair and renew the town, where it was broken down before."

After being restored to English rule, Colchester grew into a successful small town called a burh. It had special rights for its citizens. However, being several miles upriver meant it wasn't as good for sea trade as Maldon or Ipswich. A new port at Hythe helped, and foreign trade increased in the 900s. Colchester also had a mint for making coins from 991 AD.

Important meetings of wise men, called Witans, were held in Colchester by kings like Æthelstan and Edmund I. Six of the town's churches date from the Saxon period, including St Peter's and Holy Trinity with its 11th-century tower. A chapel and a large hall were built in front of the ruins of the Roman Temple of Claudius.

Medieval Era

Norman Colchester

After the Norman conquest of England in 1066, Colchester faced very high taxes. In 1069, a Danish fleet attacked the east coast, damaging Colchester. Around this time, the town was given to Eudo Dapifer, a powerful Norman lord.

Eudo oversaw the building of Colchester Castle (around 1073–1080) on the remains of the Roman Temple of Claudius. This was meant to be a royal castle, important for defending eastern England. It is the largest Norman castle ever built and the first stone Keep in England.

Under Eudo, the town grew, reaching about 2,500 people. Eudo also founded several religious places. The most important was St. John's Abbey (built 1095–1116), a Benedictine monastery. The Abbot of Colchester even had a seat in the House of Lords. Eudo was buried there in 1120.

Eudo also founded the Hospital of St Mary Magdalen in 1100, outside the walled town, to care for lepers. Another important building was St Botolph's Priory, the first Augustinian monastery in Britain. It was built outside South Gate on the site of an older Saxon church.

Secular buildings (non-religious) in Norman Colchester included the Moot Hall, which was rebuilt in 1160. It was unusually fancy for a non-religious building of that time, with carved stone doors and windows. Many houses were built using stones from old Roman ruins.

Colchester's merchants traded with Europe, sending corn to Holland. Iron working and pottery were also important industries. The town's citizens had many rights and privileges, including grazing rights, fishing rights, and protection for their market. These rights were formally written down in the 1189 Charter.

Early Medieval History

Colchester was the largest town in Essex throughout the Middle Ages. Its port at Hythe was one of the biggest in England in the early 1200s, but it later lost status to Chelmsford.

In the early 1200s, Colchester was involved in the First Barons' War. King John had to send forces to take the castle from rebellious barons in 1216. Later, a baronial army attacked and damaged the town.

The 13th and early 14th centuries saw many conflicts between the town's citizens and St. John's Abbey, as well as local lords, over their rights. For example, in 1253, Colchester citizens attacked the Abbey's gallows and ships. Later, in 1312, they fought with the powerful FitzWalter family over land and hunting rights.

The Black Death plague hit Colchester in 1348–49, killing up to 1,500 people, including the Abbot of St. John's Abbey. A second outbreak happened in 1360–61.

Late Medieval History

Despite the plague, Colchester grew due to the cloth trade from the mid-1300s. By 1377, its population reached 7,000, making it the eighth largest town in England. It grew to 9,000 by the early 1400s. Many immigrants came to the town, including from the Low Countries (modern-day Belgium and Netherlands).

Colchester was a center of the Peasants' Revolt in 1381. One of the rebel leaders, John Ball, had been a priest in Colchester. Peasants gathered here before marching to Stepney. Those who stayed attacked the Moot Hall and St John's Abbey. After the revolt was defeated, survivors attacked Colchester's Flemish population.

Disputes between the townspeople and the Abbey continued. The town was also a center for Lollardy, a Christian movement considered heretical. Lollard books were confiscated, and a tailor was burned at the stake in 1428 for being a heretic.

Colchester avoided the fighting of the Wars of the Roses. The town had strong support for the House of York. By the end of the Middle Ages, Colchester's population had started to decline to about 5,000 by 1520, due to a shrinking cloth trade.

The Medieval Town

Town Government

Colchester received its first town charter in 1189 from Richard the Lionheart. This document formally recognized the rights of Colchester's citizens, called burgesses. The charter set out how the town's leaders (bailiffs and justices) were elected.

The burgesses had many rights, including:

- Sole right to fish and shellfish in the River Colne.

- Right to use the river bank.

- Freedom from tolls when traveling in the borough.

- Right to graze animals on common land.

- Right to hunt foxes, hares, and polecats.

- A share of the town's income from fees and fines.

- The right to vote on certain matters.

The town's government changed over time. Originally, two "reeves" were the highest officials, later replaced by two "bailiffs." These bailiffs collected taxes and ran the town courts. In 1372, a new system was introduced with tighter election rules and new officials called "chamberlains" to manage the town's money.

The town was divided into four areas: North, East, South, and Head Wards. A council of 24 burgesses was formed, and from them, the town's officials were chosen. From 1295, two Members of Parliament represented Colchester.

Law

Jury courts met regularly at the Moot Hall. They heard cases about trespassing, illegal hunting, blocking or polluting water sources, theft, and damaging town walls. Prisoners waited for trial in a jail under the Moot Hall. The town's gallows were located outside the town on "Gallow's Street."

Blocking and polluting public water was a big problem. Tanners were prosecuted for dumping waste in streams. The town also protected its markets, closing down illegal ones. Poaching deer from royal forests was a serious issue. Gambling in taverns was also discouraged.

Religious Institutions

The largest and richest religious place in medieval Colchester was St John's Abbey. It was a Benedictine monastery founded in 1095. Since ordinary people couldn't worship inside, St Giles church was built nearby for them.

Other important religious places included the Augustinian St Botolph's Priory and the Franciscan Greyfriars, whose spire was the tallest building in town. There were also hospitals for the sick, like St Mary Magdalene's for lepers. Colchester had many parish churches, including St Mary-at-the-Walls, St Peter's, and Holy Trinity.

Many guilds (groups of people with the same trade or interest) were linked to churches. The biggest was the Guild of St Helena, named after Colchester's patron saint.

Colchester also had a Jewish community with its own council and synagogue in the 1200s. However, like Jews elsewhere in England, they were expelled by King Edward I in 1290.

Economy of Medieval Colchester

Colchester was the main market town for North East Essex and South West Suffolk. Local goods like grain, fish, cattle, and sheep, as well as beer, bread, and cloth, were traded here. These were also sent to other markets like Ipswich and Great Yarmouth.

Colchester pottery, including special ceramic vents called louvers, was made here and used across Essex. Roof and floor tiles were also produced.

The wool trade was the most important industry from the 1200s to the 1400s. Colchester's wool industry grew a lot after the Black Death, with many immigrants from Britain and the Low Countries. Each bale of cloth involved up to fifty people, from shepherds to merchants.

Colchester exported 40,000 bales of cloth annually, especially a grey-brown cloth called russet. The quality of Colchester's russets made them popular. Wool was exported from Colchester's Hythe port to places like Zeeland, Flanders, and Germany. In return, Colchester imported wine, spices, furs, and silk.

The wool trade changed in the 1400s with new laws to regulate it. However, wars and population decline in Europe caused the trade to shrink in the late 1400s. Despite this, the cloth industry would boom again later.

Other industries included leather working, fishing, and oyster cultivation. Colchester's oysters were sold in other towns. Clockmakers from Colchester repaired clocks in churches across Essex and Suffolk. Some wealthy Jewish residents were involved in moneylending, which was forbidden for Christians.

Layout of the Medieval Town

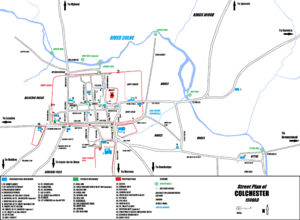

Medieval Colchester grew from the Saxon town, which was built inside the old Roman town walls. Suburbs also developed along the main roads leading out of town.

Inside the Walls

Most of the medieval town was inside the Roman walls, which were strengthened with towers in the Middle Ages. Of the original six Roman gates, two were blocked up. This left Hed Gate (modern Head Gate) as the main entrance, along with North Gate, Suth Gate (South Gate), and Est Gate (East Gate). Four new gates were also cut through the walls.

Hed Street (modern Head Street) followed the old Roman north-south road, continuing as North Street (North Hill). High Street followed the old Roman east-west road. The west end of High Street was called Corn Hill, where the corn market was. High Street was the main market area, with different sections for butter, fish, meat, and vegetables.

The Moot Hall was a stone building with fancy carvings. It had a jail in its cellar. Many inns were located on High Street, like the George and the Angel. St Nicholas and All Saints churches still stand on High Street.

North of High Street were West Stockwell Street, East Stockwell Street, and Maidenburgh Street, which led to public wells. St Martin's church was on West Stockwell Street, and St Helena's Chapel was on Maidenburgh Street. The Castle, with its buildings, was north of High Street. It served as the County Jail.

Houses were typically timber-framed with a main hall and side rooms. They often had ovens, wells, and yards. Local roof tiles and Flemish-style floor tiles were used in larger houses. Behind the street fronts were large yards, gardens, and industrial areas like metal casting pits.

The Medieval Hythe Port

Magdalene Street connected Colchester to the Hythe port. The road into the Hythe was called Hethstreet (Hythe Hill). Although separate, the Hythe was legally part of the town. It had cranes, warehouses, and boat-building sheds.

Most large ships couldn't reach the Hythe, so they unloaded cargo at Brightlingsea near the river mouth. Smaller boats then took the goods to the Hythe. Because of this, Brightlingsea became a member of the medieval Cinque Ports alliance. The Hythe was the richest parish in town due to its trade.

Trade at the Hythe increased in the late 1300s but declined in the late 1400s due to less overseas trade. Most shipping then went through London.

Dutch Quarter

Between 1550 and 1600, many Protestant weavers and clothmakers from Flanders (now Belgium) came to Colchester. They were called the 'Dutch' and were famous for making Bays and Says cloth. An area in Colchester town center is still known as the Dutch Quarter, and many buildings there are from the Tudor period. During this time, Colchester was one of England's wealthiest wool towns.

Jane Taylor, who wrote the poem Twinkle Twinkle Little Star, lived in the Dutch Quarter in the late 1700s and early 1800s.

Siege of Colchester

In 1648, Colchester was caught in the Second English Civil War. A large Royalist army entered the town, which mostly supported Parliament. They were chased by Parliament's New Model Army. The Parliamentarians besieged the town for 76 days.

During the siege, many old buildings like St. Mary's Church and the gate of St. John's Abbey were partly destroyed. The people in the town ran out of food and had to eat candles and boots. When the Royalists surrendered, their leaders, Sir Charles Lucas and Sir George Lisle, were shot at Colchester Castle. An obelisk marks the spot today.

Plague

Daniel Defoe wrote in 1722 that Colchester lost 5,259 people to the plague in 1665. This was more than many other places, even London, for its size. However, by the time he wrote this, the population had grown to about 40,000.

Colchester Earthquake

On April 22, 1884, at around 9:20 AM, the Colchester area was hit by the UK's most destructive earthquake. It was estimated to be 5.2 on the Richter Scale and lasted about 20 seconds. The quake was felt across southern England and even into Europe. Over 1,200 buildings were damaged or destroyed.

The Times newspaper reported widespread damage in villages near Colchester. Many people lost their homes. Buildings like Langenhoe church were destroyed, and a child died in Rowhedge. You can find a report on this earthquake at the Colchester local library.

Oyster Feast

The Oyster Feast is a big event in Colchester's yearly calendar. It celebrates the "Colchester Natives," which are local oysters from the Colne river. The feast has been happening since the 1300s and is held in the Moot Hall.

Colchester Army Garrison

The Colchester Garrison has been an important military base since Roman times. The first permanent army base was set up by the Roman Twentieth Legion in 43 AD. Colchester was a key barracks during the Napoleonic Wars and the Victorian era. During the First World War, many soldiers of Kitchener's Army trained there.

Today, there are plans to build a new, modern barracks outside the town. This will free up land in the town center and replace the old Victorian buildings. People hope that some of the original architecture will be saved for history.

Colchester Town Watch

Colchester Town Watch was started in 2001. It's a group of volunteers who act as a ceremonial guard for the mayor and for town events.

The Watch follows old laws from 1253 that created the first police force in the UK. Today's Watch is purely ceremonial; the Essex Constabulary handles law and order.

The Watch wears uniforms based on late Elizabethan clothing, in the town's colors of red and green. They wear helmets and body armor, and carry spears called partizans or half-pikes.

The Watch connects Colchester to its history at many events. Their special day is the Marching Watches. On the Saturday closest to the Vigil of St. John The Baptist, the Watch "walk the walls." They complete a circuit of Colchester's town wall (the oldest in Britain, with Roman parts). This ceremony, like "beating the bounds," marks the area they protect. The walk is about 3 kilometers long and ends at a local pub for refreshments. Mayors and other important people often join them.

Colchester Co-op

The Colchester and East Essex Co-operative Society was founded in 1861. Today, it is the largest independent retail chain in the region, with assets worth £65 million.

Paxman Engines

Paxman, an engine manufacturer, has been in Colchester since 1865. James Noah Paxman started a company called 'Davey, Paxman, and Davey' and opened the Standard Ironworks in the town center. In 1876, the company moved to a new site on Hythe Hill.

In 1925, Paxman made its first spring injection oil engine. The company later became part of GEC. Since the 1930s, Paxman has mainly made diesel engines. Paxman engines are famous worldwide. They are used in fast naval boats, submarines, and high-speed trains. At its busiest, the Paxman factory covered 23 acres and employed over 2,000 people.

Paxman became part of MAN Diesel in 2000. In 2003, the company planned to move manufacturing to Stockport. Production in Colchester was reduced, and the last engine was completed on September 15, 2003. However, the Stockport plant couldn't make the popular VP185 engine well, so production restarted in Colchester in 2005.

|