History of Detroit facts for kids

Detroit, the largest city in Michigan, was founded in 1701 by French colonists. It was one of the first European settlements in North America, built as a trading post for furs. In the 1800s, Detroit grew as more people settled around the Great Lakes. By 1920, it became a major industrial city, especially known for cars. It was then the fourth-largest city in the United States. It kept this important role through the middle of the 20th century.

Contents

Native American History

Evidence shows that people lived in the Detroit area about 11,000 years ago. Ancient groups known as Mound Builders created large mounds for burials and ceremonies. In the 1600s, the Huron, Odawa, Potawatomi, and parts of the Iroquois League lived here. French traders and missionaries arrived in the late 1600s. They found that many Native American villages were empty due to conflicts over the fur trade.

Early French Settlement

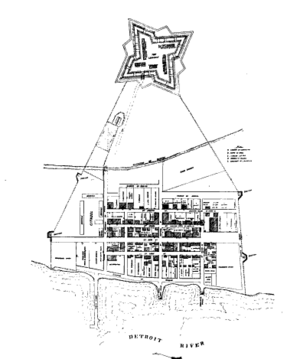

The city's name comes from the Detroit River, meaning "the strait of Lake Erie." This river links Lake Huron and Lake Erie. In 1701, Antoine Laumet de La Mothe, sieur de Cadillac, established a fort called Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit. He named it after his sponsor. Cadillac was later removed from his position because he caused problems.

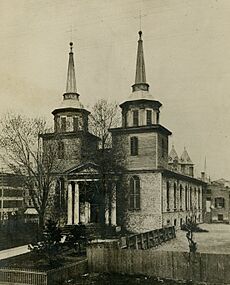

Ste. Anne de Détroit, founded in 1701, was the first building in Detroit. It is the second oldest continuously operating Catholic parish in the United States. The main business was trading furs with Native Americans. Detroit was the largest French village between Montreal and New Orleans. In 1760, the French commander surrendered Fort Detroit to the British. Control of the area went to Great Britain after the British won the Seven Years' War. The settlement was then called Detroit.

Early American Control

During the American Revolutionary War, American forces tried to reach Detroit. But travel was hard, and British-allied Native Americans stopped them. In 1783, Great Britain gave the territory, including Detroit, to the United States. However, the British kept control until 1796. In 1794, General Anthony Wayne defeated a Native American alliance. This led to a treaty where the tribes gave the Fort Detroit area to the United States.

Father Gabriel Richard arrived in 1796. He helped start schools and brought the first printing press to Michigan. In 1805, a big fire destroyed most of Detroit. Only a warehouse and some brick chimneys survived. Detroit's city motto and seal remember this fire.

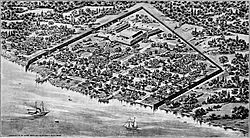

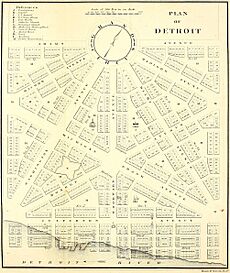

Woodward's City Plan

After the 1805 fire, Justice Augustus B. Woodward created a new city plan. It was similar to Washington, D.C.'s design. Detroit's wide avenues and traffic circles spread out from Campus Martius Park. This design helped traffic flow and created tree-lined streets and parks.

Slavery in Early Detroit

In Detroit's earliest years, slavery was practiced. Enslaved Indigenous and African people contributed to the city's development. Their labor was important for building the city and for the fur trade. Records about slavery in Detroit are not complete.

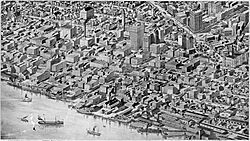

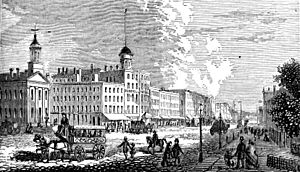

A City Emerges

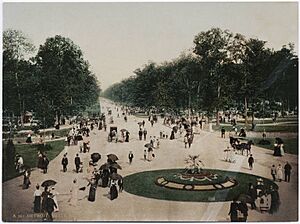

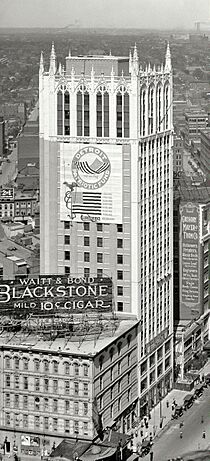

After Detroit rebuilt in the early 1800s, it became a busy center for business and industry. By the American Civil War, over 45,000 people lived in the city. The city grew along Jefferson Avenue, with many factories using the river and rail lines. In the late 1800s, Detroit was sometimes called the Paris of the West for its architecture. Many tall buildings were built downtown throughout the 1900s.

After World War II, the car industry grew quickly, and suburbs expanded. The Detroit metropolitan area became one of the largest in the United States. Immigrants and people moving from other parts of the country greatly helped Detroit's economy and culture. Later in the century, changes in industry led to fewer jobs and people. Since the 1990s, the city has been working to become strong again. Many parts of the city are now listed as historic places.

Civil War Era

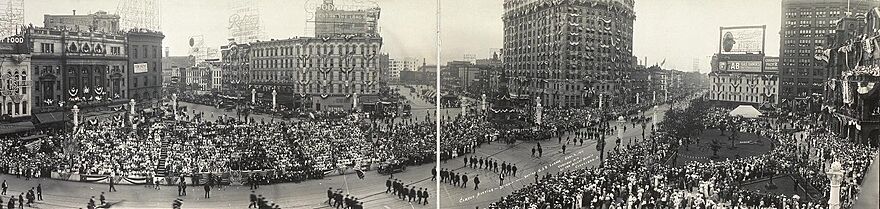

Before the American Civil War, Detroit was an important stop on the Underground Railroad. This network helped enslaved people escape to freedom in Canada. The Michigan Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument honors Michigan's role in the Civil War. Thousands of Detroiters joined volunteer regiments.

The Detroit conflict of 1863 happened on March 6, 1863. It was the city's first major incident of its kind. It resulted in deaths, injuries, and buildings being burned or damaged.

Rise of Industry and Commerce

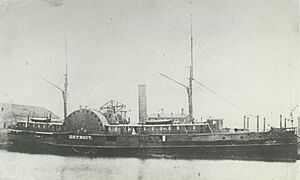

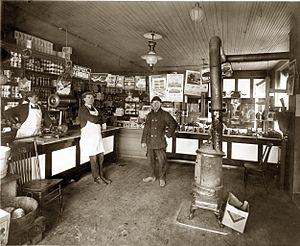

Detroit's location in the Great Lakes Region helped it become a major center for trade. It became a U.S. transportation hub. Pharmaceutical companies and tobacco manufacturers set up businesses. In the late 1800s, making cast-iron stoves became Detroit's top industry. The city was known as the "Stove Capital of the World."

The growth of manufacturing created a new group of wealthy business owners. Some built large homes east of downtown. Detroit began to expand. Other citizens built homes north of downtown along Woodward Avenue. The city has many restored historic Victorian buildings. Wealthy residents also paid for many churches.

Immigrants in the 19th Century

Detroit has always been a city of immigrants. Early French settlers came in the 1600s and 1700s. In the 1840s, Irish immigrants settled in the Corktown neighborhood. Germans were the largest group. Many German and Polish immigrants came to Detroit between 1860 and 1890.

Irish Catholics found many opportunities. They were successful in politics and construction. They built many churches. European immigrants started businesses and built communities. German immigrants built German-speaking churches on the east side of the city. Polish immigrants also arrived and built Catholic churches. Catholics were very active in building churches, schools, and hospitals.

By 1900, most Detroiters lived in single-family homes. European immigrants often owned their homes. Homeownership grew quickly in Detroit's immigrant neighborhoods.

Hazen Pingree

In 1889, Hazen S. Pingree became mayor. He worked to pave streets, which were in poor condition. He pushed for lower prices from Detroit's streetcar, gas, electric, and telephone companies. This made him very popular. He also supported a city-owned electric light plant. When a big economic downturn happened in 1893, he helped by opening empty lots for people to grow food. Pingree was an important American mayor in the 1890s. He later became governor of Michigan.

20th Century

Henry Ford and the Automobile Industry

Henry Ford changed the car industry when he created the assembly line in 1910. This invention transformed mass production. Detroit's location made it easy for car makers to get money and sell their products. The car industry grew fast, making Detroit the Motor City.

In 1914, Ford started paying workers five dollars a day. This was about double the usual rate. This attracted workers and increased productivity. By the 1920s, Ford faced competition from General Motors, which offered more choices. In 1935, the United Auto Workers labor union was founded in Detroit.

The car industry's growth needed many workers. New laws reduced foreign workers. So, Ford started hiring African Americans. Many moved to Detroit from the South during the Great Migration. This large number of new workers made Detroit's population soar. The city also expanded its borders. This led to a shortage of homes.

The rise of cars also meant rethinking city transportation. Bridges were built to separate train and car traffic.

Progressive Movement

The Progressive Era began in the 1890s. People worked to improve society and fix problems. Reinhold Niebuhr, a minister, spoke out against harsh working conditions in the car industry. He believed that factory work was hard for workers.

Gilded Age

At the start of the 1900s, wealthy areas led to even fancier neighborhoods. Many beautiful churches were built. Wealth from the car industry led to a boom in downtown Detroit. Many tall buildings, called skyscrapers, were built. The Guardian Building (1928) and The Fisher Building (1928) are notable examples.

Shopping areas grew along Park Avenue and Woodward. The J. L. Hudson Department Store became a huge complex. Many hotels and grand movie theaters were built. Public buildings like Orchestra Hall (1919) and the Detroit Public Library (1921) were also constructed.

Immigrants in the 20th Century

The car industry's growth brought many immigrants from Europe and Canada. It also brought Black people from the South. These new residents filled the demand for workers. They changed neighborhoods and brought jobs and money to local communities. Social class and race became more important in how neighborhoods were organized.

Early immigrants came from Greece and Italy. By 1914, Jewish people from Eastern Europe also settled in Detroit. African Americans, many of whom moved from the South during World War II, faced challenges. Many lived in crowded and poorly maintained homes.

Detroit's population grew from 265,000 in 1900 to over 1.5 million in 1930. Polish immigrants contributed to this growth. The Great Depression and World War II brought more people to the city, mostly from within the United States. By 1960, African Americans made up over a quarter of the city's residents. After 1970, Arabs, especially Palestinians, also moved to Detroit.

Detroit also grew in size during the 1900s. It added nearby villages and land. Detroit's growth owes a lot to the car industry. The promise of jobs attracted people from many places. Today, Detroit is still a large city. But it has lost some of its diversity to the suburbs. The remaining citizens face social and economic challenges.

Local Politics

Local politics shifted from ethnic communities to business leaders in the early 1900s. In 1918, the city council changed, reducing the power of ethnic groups. After 1930, the Democratic Party grew strong again, joining with the United Auto Workers union. In 1974, Coleman Young was elected mayor. He was the first Black mayor and represented the city's new majority.

Women in the 20th Century

Most young women worked before marriage. Nursing became a professional career in the late 1800s. Women's clubs promoted community involvement, focusing on public health and safety.

World War II encouraged women to take on more active roles in society. As men joined the military, women worked in factories. More women became the main earners for their families. However, women still faced barriers. They were often kept out of jobs usually done by men. Employers paid women less and offered fewer benefits. African American women faced unfair treatment based on both their race and gender.

Great Depression

The Great Depression hit Detroit hard. Car sales dropped, and many people lost their jobs. Mayor Frank Murphy promised no one would go hungry. He set up relief efforts. In 1933, Frank Couzens became mayor. He improved the city's finances and got federal money for relief.

Labor Unions

As Detroit became more industrial, workers formed labor unions like the United Auto Workers. These unions helped workers with wages and benefits. By 1950, over 50% of Detroit's workers belonged to a union. This gave them more power.

However, unions were less helpful for people of color. Their rules sometimes allowed unfair hiring practices. Over time, unions became more diverse. They worked with African American churches and civil rights groups. This helped African American workers get more benefits and jobs.

World War II and the "Arsenal of Democracy"

When the United States entered World War II, Detroit's factories made tanks, jeeps, and bombers. Detroit made a huge contribution to the war effort. It was called America's Arsenal of Democracy.

Detroit's wartime boom attracted many Southern Black people. They sought jobs and freedom from unfair Jim Crow laws. The military draft caused a worker shortage. Car plants had to hire Black workers.

As Detroit's Black population grew, housing became very scarce. Some landlords charged very high rents in Black neighborhoods. Homes in Black neighborhoods became run-down. Some white homeowners unfairly blamed Black poverty. This made them want to keep neighborhoods separate.

Local housing policies made Black neighborhoods even more separate. Practices like "redlining" limited where Black people could live. Racially unfair housing rules further limited options. Tensions over limited housing grew as veterans returned. This led to conflicts in the 1950s and 1960s.

Postwar Era

From 1945 to 1970, the car industry had its most prosperous quarter-century. People wanted cars to drive from work to spacious homes in the suburbs. Highways were built for cars, which had more funding than public transportation.

Replacing Detroit's large electric streetcar network with buses and highways was controversial. Mayor Albert Cobo supported freeways. He urged the city council to sell the city's modern streetcars. On April 8, 1956, the last streetcar ran down Woodward Avenue.

White ethnic groups enjoyed good wages and suburban lifestyles. Black people started in unskilled jobs, making them vulnerable to layoffs. A large, well-paid Black middle class grew. They also wanted to own homes and moved out of crowded areas.

As mayor from 1957 to 1962, Louis Miriani completed many large city improvement projects. He also took steps to address rising crime. Tensions grew, leading to the 1967 conflict. The 1970s brought high gasoline prices. American car makers faced strong competition from imported cars.

Civil Rights and the Great Society

In June 1963, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. gave an important speech in Detroit. Detroit played a big role in the civil rights movement of the 1960s. The Model Cities Program tried new anti-poverty programs. This program helped create a new generation of mostly Black city leaders.

Detroit saw growing tensions between the mostly white police force and Black people in the inner city. This led to a large conflict in July 1967. It started in mostly Black neighborhoods. The result was 43 people dead, 467 injured, and over 2,000 buildings destroyed. Thousands of small businesses closed or moved. The affected area was in ruins for decades.

Coleman Young, Detroit's first Black mayor, explained the long-term effects. He said the conflict led to economic problems and many people leaving the city.

Milliken v. Bradley

In 1970, the NAACP sued Michigan state officials, claiming public schools were separated by race. The Supreme Court ruled that schools were controlled locally. Suburbs could not be forced to solve problems in the city's school district. This decision made it harder to integrate schools in northern cities. It protected suburbs from integration by ignoring how their neighborhoods became racially separate.

1970s and 1980s

In 1970, 55 percent of Detroiters were white. By 1980, this dropped to 34 percent. The move of white people to the suburbs left Black people in control of a city with less tax money and fewer jobs. Detroit faced high unemployment and poverty rates throughout the 1980s.

In the 1973 mayoral election, Black voters mostly supported Coleman Young. White voters mostly supported John Nichols. Young, the new mayor, worked with Detroit's business leaders. He supported building the Joe Louis Arena and improving public transportation. He won re-election many times, serving 20 years as mayor.

In 1987, Northwest Airlines Flight 255 crashed near Detroit, killing almost everyone on board.

Decline of Detroit

Detroit has experienced a major decline in recent decades. The city's population has fallen from 1,850,000 in 1950 to 680,000 in 2015. Crime rates have been high, and large areas of the city show severe urban decay. In 2013, Detroit filed the largest city bankruptcy case in U.S. history. It successfully exited bankruptcy in December 2014.

As of 2017, the average household income is rising. Crime is decreasing by 5% each year.

Contributors to Decline

The loss of industries in Detroit has been a major reason for the city's population decline.

Role of the Automobile Industry

Before cars, Detroit was a small manufacturing center. The car industry grew to be the biggest in the city. It brought many new residents. The car industry also created many high-paying management jobs. These workers began moving to suburbs.

City planning focused on cars. Money went to building expressways for cars. This hurt public transportation and inner-city neighborhoods.

By 1960, Detroit had a mostly African American inner city. It was surrounded by mostly white outer areas and suburbs. The car industry also started moving away from Detroit. This was easier as the "Big Three" (General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler) controlled most car production. They moved production out of central Detroit.

When car factories moved out, it hurt Detroit's economy. The city lost tax money and population. Closed car plants were often left empty. By the mid-1960s, the city's decline was linked to the car industry leaving.

By the 1970s and 1980s, the car industry faced more problems. Gas prices rose sharply. There was strong competition from imported cars. Detroit residents had fewer good-paying car manufacturing jobs. Detroit's leaders did not diversify the city's industries beyond cars.

Racial Housing Segregation

During World War II, more jobs opened for Black workers. But white workers often opposed racial integration. White middle-class residents used unfair practices to keep neighborhoods separate. They limited where Black people could live and own homes.

After the war, economic problems and high rents made life hard for Black communities. These areas became run-down. The New Deal tried to expand homeownership. But its housing policies did not help Black homeownership equally. Practices like "redlining" limited where Black Detroiters could move. This protected property values for white middle-class homes.

Neighborhood associations, made of white homeowners, also worked to keep neighborhoods separate. They used "restrictive covenants." These were legal rules that prevented Black people from buying homes in certain areas. These rules protected property values in white neighborhoods. In the mid-1900s, the Supreme Court ruled that restrictive covenants were unconstitutional. Neighborhood associations then found other ways to prevent Black families from moving in.

Neighborhood associations also influenced politics. They supported politicians who opposed public housing and racial integration. This led to continued racial separation. The unfair exclusion of Black families from homeownership meant they missed out on economic benefits.

Open Housing Movement

In 1948, the Supreme Court ruled that enforcing racially unfair housing rules was illegal. This encouraged efforts for integrated neighborhoods. Wealthy African Americans began moving into white neighborhoods. Many white residents feared that if Black people moved in, their home values would drop. Some real estate agents used this fear to trick white people into selling their homes cheaply. Many white residents then moved to the suburbs. This "white flight" took away residents and tax money from the city.

1950s Job Losses

After the war, Detroit lost nearly 150,000 jobs to the suburbs. Major companies closed or shrank. In the 1950s, unemployment was around 10 percent.

1950s to 1960s Freeway Construction

By the late 1940s, unfair housing rules had hurt living standards for many African Americans. Their neighborhoods were seen as "slums" that needed to be cleared. In 1949, buildings in Black Bottom began to be torn down. When new highways were planned, Black Bottom and Paradise Valley were chosen. Many residents were forced to move and faced greater poverty. The effects of highway construction are still felt by Black businesses in Detroit today.

Detroit Conflicts

The Detroit conflict of 1943 resulted in deaths, injuries, and property damage. In the summer of 1967, Detroit saw five days of major conflict. Forty-three people died, and many were injured. Over 2,000 buildings were destroyed.

Economic and Social Impact of the 1967 Conflicts

After the 1967 conflicts, thousands of small businesses closed or moved. The affected district remained in ruins for decades. The conflict led to economic problems and many people leaving the city.

1970s and 1980s

By 1980, the white population in Detroit had dropped significantly. The move of white people to the suburbs left Black people in control of a city with less tax money and fewer jobs. Detroit faced high unemployment and poverty rates. Detroit also faced challenges with safety. Residents sometimes set fires to empty houses. The city now organizes "Angel's Night" every year, with volunteers patrolling high-risk areas.

Problems

Urban Decay

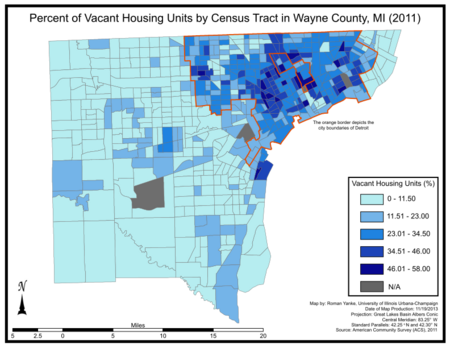

Detroit has experienced significant urban decay. This is when a city falls into disuse and disrepair. It often has empty land, abandoned buildings, high unemployment, and high crime rates. Many homes and businesses are empty. The city's large size makes urban decay worse. The mayor proposed tearing down old buildings to improve city services.

The average price of homes sold in Detroit in 2012 was very low. Many property owners did not pay taxes. A study in 2014 found about 50,000 abandoned structures.

Between 2000 and 2010, Detroit lost a quarter of its population. However, from 2010 to 2018, Detroit saw growth in racial diversity. White residents moved into downtown and midtown. But African American neighborhoods still lack good public services. The city's poverty rate is still much higher than the national average.

Population Decline

Detroit has seen a big drop in population, losing over 60% of its people since 1950. Most of this loss was due to industries leaving Detroit. Factories moved to the suburbs. This was combined with "white flight." Many white families moved from Detroit's urban areas to the suburbs. This caused overcrowding in the inner city and led to racial separation in housing.

Highway construction after World War II also contributed to white flight. This allowed white families to easily drive to work in the city from the suburbs. This made existing racial separation worse.

As a result of white flight, Detroit's racial makeup changed greatly. By the 1980s, Detroit became a majority-Black city for the first time. This had political, social, and economic effects. The city's tax money greatly decreased. This led to more home foreclosures and unemployment. It eventually led to the city's bankruptcy in 2013.

Detroit's population continues to decline today. This affects its mostly poor, Black population the most. Unfair loan policies contributed to white flight. The remaining poor, Black city residents faced a lack of investment and public services. Detroit has the highest property tax of any major U.S. city.

White flight seems to be slowing down since the 1990s. Wealthy white families are returning to the city. But this has caused problems with people being displaced. This affects minority communities more. Real estate development leads to higher rents. This pushes out minority groups and poorer residents.

Data shows that Detroit's population loss is slowing. As of 2021, the population declined further to 630,000.

Social Issues

Unemployment

According to the U.S. Department of Labor, the unemployment rate was 8.3% as of October 2017.

Poverty

The U.S. Census Bureau reported that Detroit had the highest percentage of people living below the poverty level among 71 U.S. cities in 2012.

City Finances

On March 1, 2013, Governor Rick Snyder announced that the state would take financial control of Detroit. The city was found to be "clearly unable to pay its bills." It faced a large budget deficit and long-term debt. On July 18, 2013, Detroit filed for bankruptcy. It was the largest U.S. city ever to do so. On December 10, 2014, Detroit successfully exited bankruptcy.

In March 2014, the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department began cutting off water to homes with unpaid bills.

The city's financial crisis led to Michigan taking administrative control. The city's plan for exiting bankruptcy was approved. It allowed the city to remove debt and invest in improved city services. The Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) helped fund the city's recovery.

Resurgence

By the late 2010s, many saw Detroit's economy and culture improving. This was due to private and public investments. Detroit gained new interest through reinvestment. It serves as a model for other areas to revitalize their cities. In 2024, the United States Census Bureau reported a slight population increase in Detroit's 2023 estimates. This was the city's first recorded growth since 1957.

Evidence of Detroit's resurgence is clear in the Midtown Area and Central Business District. Dan Gilbert has invested heavily in improving historic buildings downtown. The focus is on making downtown attractive for technology companies. Public transportation downtown has also seen private investment. Gilbert has also invested in improving safety downtown, working with local police.

However, some people have concerns. They argue that private money downtown has changed the city's character. Some claim a few powerful investors might have too much control. Residents worry about having to move because rents are increasing. Many long-time residents also fear new money could reduce their political power.

Other investors, like John Hantz, are trying urban agriculture. Hantz focuses on run-down neighborhoods. He proposed tearing down old homes and planting trees to create a large urban farm. The city government approved his plan.

Detroit's resurgence is also driven by partnerships between public, private, and nonprofit groups. These groups protect and maintain Detroit's valuable assets, like the Detroit Riverfront.

Over the past seventy years, Detroit has seen a big drop in population and economic well-being. This has caused financial problems for many residents. Property taxes are often too high. This leads to more home foreclosures. These properties are often bought by wealthy investors.

Supporters of such investment say it helps by improving empty areas. However, this can cause people to be displaced. It can also lead to "cultural displacement." This means long-time residents lose their sense of belonging. While new money brings jobs, opponents say it only benefits the wealthy. They fear rising property values will hurt existing populations.

In 2015, activists started a community land trust (CLT). This aims to provide affordable housing. The CLT helps residents by covering property taxes and other costs. Residents pay one-third of their income in rent. Sales caps keep homes affordable for future buyers.

Some are unsure about CLTs because they rely on outside money. This can take away their independence.

Metropolitan Region

The Detroit area became a major metropolitan region with the building of many freeways in the 1950s and 1960s. The 1950s, 60s, and 70s saw the rise of U.S. muscle cars. Freeways made it easy to travel. People moved from the city to the suburbs for newer housing and schools. Downtown Detroit has seen a comeback in the 21st century. It is now a business and entertainment center, with three casino hotels. In 1940, Detroit had about one-third of Michigan's population. Today, the metropolitan region has roughly half of the state's population. The city completed major improvements in the 1990s and early 2000s. Immigration continues to help the region grow.

21st Century

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the city began to improve. Much of this was in Downtown, Midtown, and New Center. Mike Ilitch and Marian Ilitch moved Little Caesars' headquarters downtown. One Detroit Center (1993) was built. The city has three casino hotels. New downtown stadiums Comerica Park and Ford Field were built for the Detroit Tigers and Detroit Lions. Little Caesars Arena opened in 2017 for the Detroit Red Wings and Detroit Pistons. This makes Detroit the only North American city with all major professional sports teams based downtown. The city has hosted major sports events, leading to many improvements.

The city's International Riverfront is a focus of much development. In 2007, Detroit finished major parts of the River Walk. The Renaissance Center was greatly renovated in 2004. New developments aim to boost tourism.

Campus Martius, a new park downtown, opened in 2004. It is considered one of the best public spaces. In 2001, the first part of the International Riverfront redevelopment was finished.

In 2004, Compuware established its world headquarters downtown, followed by Quicken Loans in 2010. Significant landmarks like the Fox Theatre have been restored. Many downtown centers attract visitors.

In September 2008, Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick resigned after problems. His actions cost the city money. About half of Detroit's property owners did not pay their 2011 tax bills.

In July 2013, Michigan's state-appointed emergency manager asked a federal judge to place Detroit into bankruptcy protection. In March 2014, the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department began cutting off water to homes with unpaid bills.

The city's financial crisis led to Michigan taking administrative control. On July 18, 2013, Detroit became the largest U.S. city to file for bankruptcy. It successfully exited bankruptcy on December 11, 2014. The plan allowed the city to remove debt and invest in improved city services. The Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) helped fund the city's recovery.

2010s and Revitalization

One of the biggest efforts after bankruptcy was fixing the city's broken street lighting. Construction finished in December 2016. Detroit is the largest U.S. city with all LED street lighting.

In the 2010s, citizens and new residents started projects to improve the city. These included volunteer renovation groups and urban gardening. Miles of parks and landscaping have been completed.

Michigan Central Station, once a symbol of decline, was renovated. In 2018, Ford Motor Company bought the building. Several other landmark buildings have been privately renovated. Detroit is seen as a city of rebirth.

The city has seen an increase in new development. This has brought wealthy families. But it has also caused some long-time residents to be displaced. Areas outside downtown have lower average incomes. Rents and living costs in developed areas rise each year. This pushes out minority groups and poorer residents.

Data shows that Detroit's population loss is slowing. As of 2021, the population declined further to 630,000.

Timeline

| Historical populations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Census | City | Metro | Region | |

| 1810 | 1,650 | N/A | N/A | |

| 1820 | 1,422 | N/A | N/A | |

| 1830 | 2,222 | N/A | N/A | |

| 1840 | 9,102 | N/A | N/A | |

| 1850 | 21,019 | N/A | N/A | |

| 1860 | 45,619 | N/A | N/A | |

| 1870 | 79,577 | N/A | N/A | |

| 1880 | 116,340 | N/A | N/A | |

| 1890 | 205,877 | N/A | N/A | |

| 1900 | 285,704 | 542,452 | 664,771 | |

| 1910 | 465,766 | 725,064 | 867,250 | |

| 1920 | 993,678 | 1,426,704 | 1,639,006 | |

| 1930 | 1,568,662 | 2,325,739 | 2,655,395 | |

| 1940 | 1,623,452 | 2,544,287 | 2,911,681 | |

| 1950 | 1,849,568 | 3,219,256 | 3,700,490 | |

| 1960 | 1,670,144 | 4,012,607 | 4,660,480 | |

| 1970 | 1,514,063 | 4,490,902 | 5,289,766 | |

| 1980 | 1,203,368 | 4,387,783 | 5,203,269 | |

| 1990 | 1,027,974 | 4,266,654 | 5,095,695 | |

| 2000 | 951,270 | 4,441,551 | 5,357,538 | |

| 2010 | 713,777 | 4,296,250 | 5,218,852 | |

| *Estimates Metro: Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) Region: Combined Statistical Area (CSA) |

||||

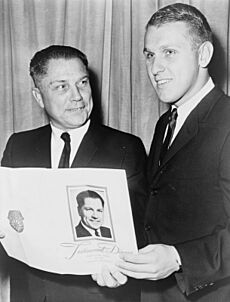

Keys to the City

Numerous people have been awarded the key to the city of Detroit. Some notable recipients include:

- Sammy Davis Jr. – Entertainer (awarded 1961 by Mayor Louis Miriani)

- Stevie Wonder – Motown recording artist (awarded 1974 by Mayor Coleman Young)

- Martha Jean Steinberg – Radio broadcaster and pastor

- Santa Claus – Given annually at the city's Thanksgiving Day Parade

- James Earl Jones – Actor

- Elmo – Sesame Street character

- Benjamin Carson – Neurosurgeon

- Jerome Bettis – Football player (awarded 2006 by Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick)

- Big Sean – Rapper

- Steve Yzerman – Retired ice hockey player (awarded 2007 by Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick)

- Mike Ilitch – Businessman and sports team owner (awarded 2008 by Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick)

- Saddam Hussein – former Iraqi president (awarded 1980 in recognition of large donations to a church)

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Detroit para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Detroit para niños

| Tommie Smith |

| Simone Manuel |

| Shani Davis |

| Simone Biles |

| Alice Coachman |