History of Knoxville, Tennessee facts for kids

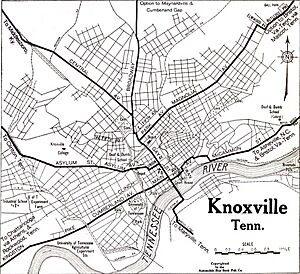

The History of Knoxville, Tennessee began when James White's Fort was built in 1786. This fort was chosen as the capital of the Southwest Territory in 1790. The city was named Knoxville in honor of Secretary of War Henry Knox the next year.

Knoxville became the first capital of Tennessee in 1796. It grew steadily in the early 1800s as a stop for people moving west. It also became a trading center for nearby mountain towns. When the railroad arrived in the 1850s, Knoxville's population and businesses grew a lot.

Even though it was a Southern city, many people in Knoxville supported the Union during the American Civil War. The city was divided during the war. Confederate forces held the city until September 1863, when Union troops arrived. Later that year, Confederate forces tried to take the city but failed during the Battle of Fort Sanders.

After the war, new business leaders, many from the North, started big iron and textile factories in Knoxville. The city became a major trading hub, connecting rural mountain towns with large manufacturing centers. Tennessee marble, found nearby, was used in many famous buildings across the country. This earned Knoxville the nickname, "The Marble City."

Knoxville's economy slowed down in the early 1900s. Political disagreements made it hard to improve the city for a long time. However, new federal groups like the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) in the 1930s and the growth of the University of Tennessee helped keep the economy stable. Starting in the late 1960s, city leaders became more open to change. Economic growth, city improvements, and hosting the 1982 World's Fair helped Knoxville become more lively.

Contents

Early history of Knoxville

Native American settlements

The first people to live in what is now Knoxville arrived during the Woodland period (around 1000 B.C. to 1000 A.D.). Two important ancient structures are burial mounds from this time. One is in Sequoyah Hills, and the other is on the University of Tennessee campus. Larger village sites from the Mississippian culture (around 1100 to 1600 A.D.) have been found nearby.

The Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto likely traveled through this area in 1540. He may have visited a village near modern Lenoir City. Another Spanish trip led by Juan Pardo might have visited villages in 1567. Records from these trips suggest the area was part of a larger Native American chiefdom called Chiaha.

By the 1700s, the Cherokee tribe was the main group in East Tennessee. They often fought with the Creeks and Shawnee. The Cherokee called the Knoxville area kuwanda'talun'yi, meaning "Mulberry Place." Most Cherokee people lived in settlements southwest of Knoxville, along the Little Tennessee River.

Building White's Fort

In 1786, a man named James White moved to the future site of Knoxville. He and James Connor built a fort there, which became known as White's Fort. The fort was on a hill, with the river to the south and creeks on the east and west. It had four strong log cabins connected by a tall fence. White also built a mill nearby to grind grain.

White's Fort was the western edge of the State of Franklin. This was a new state that Tennessee settlers tried to form in 1784. James White supported this new state. However, the U.S. government never recognized the State of Franklin. By 1789, its supporters rejoined North Carolina.

In 1789, James White, William Blount, and John Sevier helped North Carolina approve the U.S. Constitution. After this, North Carolina gave its Tennessee land to the federal government. In May 1790, the United States created the Southwest Territory. President George Washington made Blount the governor.

Knoxville is founded

Governor Blount moved to White's Fort because it was in a central location. He worked to settle land arguments between the Cherokee and white settlers. In the summer of 1791, he met with Cherokee chiefs to sign the Treaty of Holston. This treaty moved the border of Cherokee lands further west.

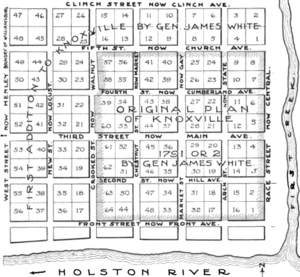

Blount first wanted the capital to be where the Clinch and Tennessee rivers met. But he couldn't get the Cherokee to give up that land. So, he chose White's Fort as the capital. James White set aside land for a new town. His son-in-law, Charles McClung, surveyed the land and divided it into 64 lots. Land was also set aside for a church, cemetery, courthouse, jail, and a college.

On October 3, 1791, people bought lots in the new city. It was named "Knoxville" to honor Secretary of War Henry Knox. Important people who bought land included merchants, a newspaper publisher, a minister, and a tavern owner.

Life in Knoxville in the 1790s

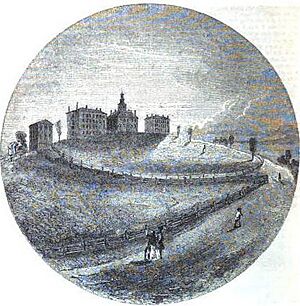

After selling the lots, Knoxville's leaders built a courthouse and jail. Federal soldiers built a blockhouse (a small fort) in 1792. The first general store opened in August 1792. The city's first newspaper, the Knoxville Gazette, started in November 1791. In 1794, Blount College, which later became the University of Tennessee, was started.

Early Knoxville was a busy frontier town. A group of Cherokee, called the Chickamaugas, did not accept the Holston treaty. They were a constant threat. In September 1793, a large force of Chickamaugas attacked a nearby settlement. A visitor in 1794 noted that Knoxville had many taverns but no churches.

In 1795, James White set aside more land for the growing city. A count that year showed Tennessee had enough people to become a state. In January 1796, leaders from across Tennessee met in Knoxville. They wrote a constitution for the new state. Tennessee joined the United States on June 1, 1796. Knoxville was chosen as the first state capital.

Knoxville before the Civil War

A growing frontier capital

Knoxville's population grew steadily in the early 1800s. Many new people were travelers passing through on their way west. About 200 travelers came through the town every day by 1807. Cattle drovers, who moved herds of cattle to markets, also visited often. City merchants got goods from distant cities using wagon trains.

A French botanist visited Knoxville in 1802. He reported about 100 houses and 10 "well-stocked" stores. He noted that trade was active, but the only industries were tanneries and blacksmiths. In 1812, a big celebration was held in the city for the start of the War of 1812.

On October 27, 1815, Knoxville officially became a city. The city's new rules set up a government where elected officials chose a mayor. This system lasted until the early 1900s. In January 1816, Judge Thomas Emmerson became Knoxville's first mayor. Knoxville remained the capital of Tennessee until 1817.

Challenges of being isolated

Knoxville's economic growth was slow in the early 1800s because it was isolated. The mountains made road travel difficult. Wagon trips to distant cities took months. Flatboats carried goods to New Orleans as early as 1795. But river dangers near Muscle Shoals made these trips risky.

In the 1790s, several roads were built to connect Knoxville to other settlements. These roads often followed old Native American trails. Kingston Pike was built in 1792. Around 1810, stagecoach service started in Knoxville. This helped break the isolation, but trips were still long and rough.

State leaders from East Tennessee often argued with leaders from other parts of the state. They wanted more money for roads and river improvements. In 1828, a steamboat, the Atlas, finally made it upriver to Knoxville. River improvements in the 1830s helped. But by then, city merchants were focused on building railroads.

Life in Knoxville, 1816–1854

In 1816, a new newspaper, the Knoxville Register, was started. It also published books, including one of the state's first histories. The Register celebrated when East Tennessee College moved to a new location in 1826. It also encouraged the Knoxville Female Academy to start classes in 1827.

In 1842, an English writer visited Knoxville. He said the city had a university, an academy, a "ladies' school," three churches, two banks, two hotels, and many stores. He also noted several "handsome country residences" owned by wealthy people.

In 1816, a merchant built a grand hotel on Gay Street. It was later known as the Lamar House Hotel. This hotel was a popular meeting place for the city's important people for many years. In 1848, the Tennessee School for the Deaf opened in Knoxville. This helped the city's economy. In 1854, land was given for Market Square. This created a place for farmers to sell their goods.

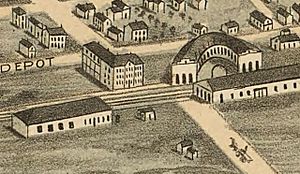

The arrival of railroads

As early as the 1820s, Knoxville's business leaders saw railroads as a way to end the city's isolation. They wanted a rail line connecting Knoxville to Cincinnati, Ohio, and Charleston, South Carolina. The Hiwassee Railroad was planned to connect with another line in Georgia.

Despite great excitement, a financial downturn in the late 1830s stopped the railroad plans. Construction of the Hiwassee Railroad was delayed. It was renamed the East Tennessee and Georgia Railroad in 1847. Construction finally began the next year. The first train arrived in Knoxville on June 22, 1855, to a huge celebration.

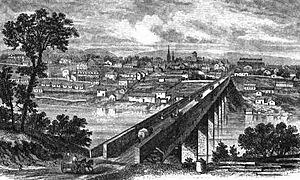

With the railroad, Knoxville grew quickly. The city's population jumped from about 2,000 in 1850 to over 5,000 in 1860. Local crop prices went up. The number of wholesale businesses grew from 4 to 14. Two new factories were built: one for steam engines and one for railroad cars. By 1859, the city had four hotels, at least seven factories, six churches, three newspapers, four banks, and over 45 stores.

Knoxville and the Civil War

Slavery in Knoxville

By 1860, enslaved people made up 22% of Knoxville's population. This was higher than the rest of East Tennessee but lower than other Southern areas. Most farms in Knox County were small. They focused on livestock, which did not require as much labor.

Most of Knoxville's leaders, even those who opposed leaving the Union, supported slavery at the start of the Civil War. Some had always supported slavery. Others, who had once been against slavery, changed their views by the 1850s.

One historian suggests that strong actions by Northern abolitionists pushed some Southerners to support slavery. By the late 1850s, most of Knoxville's leaders supported slavery.

The secession debate

The election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860 made the debate about leaving the Union much stronger in Knoxville. City leaders met on November 26 to discuss it. Those who wanted to leave the Union believed it was the only way to protect Southern rights. Those who opposed leaving believed East Tennesseans would be controlled by Southern plantation owners.

In February 1861, Tennessee voted on whether to hold a meeting to consider joining the Confederacy. In Knoxville, 77% voted against this, showing support for the Union.

Throughout early 1861, Union and Confederate leaders argued in newspapers and speeches. Both sides held recruiting rallies on Gay Street. After the attack on Fort Sumter in April, Governor Isham Harris moved to align Tennessee with the Confederacy. Union supporters in East Tennessee formed a group that met in Knoxville. They told Governor Harris his actions were wrong.

In a second statewide vote on June 8, 1861, most East Tennesseans still rejected leaving the Union. However, the measure passed in other parts of Tennessee, and the state joined the Confederacy. In Knoxville, the vote was 777 to 377 in favor of leaving. But many Confederate soldiers from outside the county were allowed to vote. Without their votes, Knoxville would have voted against leaving. After the vote, Union supporters asked to form a separate, Union-aligned state. This was rejected, and Governor Harris sent Confederate troops into the region.

Civil War in Knoxville

Confederate control

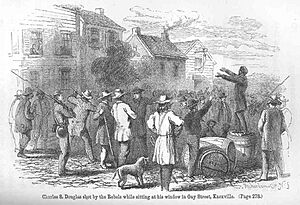

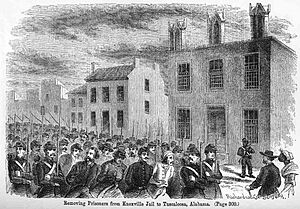

The Confederate commander in East Tennessee, Felix Zollicoffer, was at first easy on Union supporters. But in November 1861, Union fighters destroyed several railroad bridges. This led Confederate leaders to declare martial law (military rule). People suspected of burning bridges were tried and executed. Hundreds of other Union supporters were jailed, making the county jail very crowded.

Confederate commanders in East Tennessee changed often. In June 1862, George Wilson, one of Andrews' Raiders, was tried and found guilty in Knoxville. In July 1862, 40 Union soldiers captured by Nathan Bedford Forrest were marched down Gay Street.

Knoxville's district sent representatives to both the U.S. Congress and the Confederate Congress. Union supporters like Horace Maynard and Andrew Johnson kept asking President Lincoln to send troops into the region. For almost two years, Union generals ignored orders to march on Knoxville. On June 20, 1863, Union cavalry briefly tried to take Knoxville, but Confederate citizens defended the city.

Union control

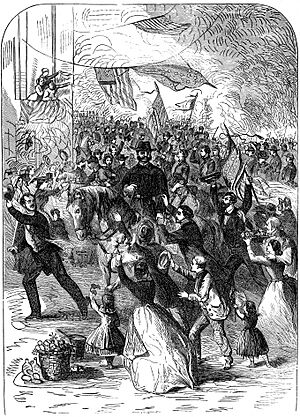

In August 1863, the last Confederate commander in Knoxville left the city. On September 1, Union General Ambrose Burnside's troops entered the city to a big welcome. Union supporters cheered, and the pro-Union mayor raised a large American flag he had saved. Burnside set up his headquarters in a house on Gay Street.

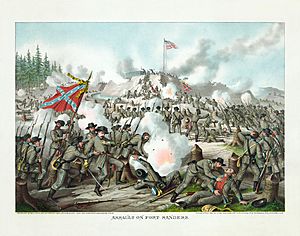

Burnside and his engineer, Orlando Poe, quickly built forts and trenches around the city. In November 1863, Confederate General James Longstreet moved north to try and force Burnside out of Knoxville. Burnside's forces delayed Longstreet at the Battle of Campbell's Station on November 16. But they had to retreat back to Knoxville with Longstreet following. General Sanders was badly wounded on November 18 while delaying the Confederates. Fort Loudon, one of the city's forts, was renamed "Fort Sanders" in his honor.

Longstreet's forces surrounded Knoxville for two weeks. The Union Army was able to get supplies to Burnside by river. On the morning of November 29, 1863, Longstreet attacked Fort Sanders. The Confederate attackers struggled against the Union trenches and gunfire. They had to retreat after only 20 minutes. On December 2, Longstreet ended the siege and left for Virginia. Knoxville remained in Union hands until the end of the war.

After the war

In April 1864, the East Tennessee Union Convention met again in Knoxville. Many supported recognizing the Emancipation Proclamation. Business leaders from both sides began working together to rebuild the city. However, some Union leaders were still angry. They took property from Confederate leaders and forced Confederate supporters out of the city.

Some acts of Civil War-related violence continued in Knoxville for years after the war ended.

Knoxville's growth after the Civil War (1866–1920)

Economic boom

Knoxville grew from a town to a city between 1870 and 1900. Many new people from the North, with help from local business leaders, started the city's first big industries. The Knoxville Iron Company was started in 1868. The next year, leaders bought the city's two main railroads. They combined them into the East Tennessee, Virginia and Georgia Railway. This railway eventually controlled over 2,500 miles of tracks in five states. The city's textile industry grew with the start of Knoxville Woolen Mills and Brookside Mills in the 1880s.

Knoxville had long been a trading center for the surrounding mountain region. Rural merchants bought goods for their stores from Knoxville wholesalers. With the railroad, the city's wholesale business grew quickly. By 1896, there were 50 such firms. In 1866, a Knoxville company was the most profitable in the state. By the late 1890s, Knoxville had the third-largest wholesale market in the South.

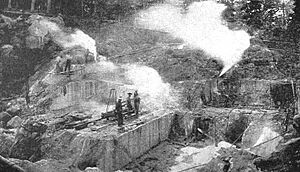

The railroad also led to a boom in quarrying and producing Tennessee marble. This type of stone was found in large amounts around Knoxville. By the early 1890s, 22 quarries and three finishing mills were operating in Knox County. The industry made over a million dollars in profits each year. Tennessee marble was used in many large buildings across the country. This earned Knoxville the nickname, "The Marble City." The Flag of Knoxville, Tennessee uses white to symbolize marble and shows a derrick used in mining.

Changes in population

Before the 1850s, Knoxville's population was mostly European-American Protestants. There was also a small community of free African Americans and enslaved people. Railroad construction in the 1850s brought many Irish Catholic immigrants. They helped start the city's first Catholic church in 1855. Swiss immigrants were also important in the 1800s. Welsh immigrants brought mining and metalworking skills in the late 1860s and 1870s.

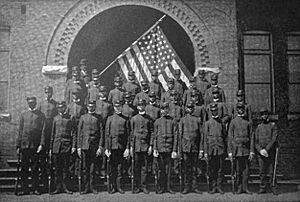

After the Civil War, African Americans played a bigger role in the city's politics and economy. Cal Johnson, born enslaved, became one of the wealthiest African Americans in the state. Attorney William F. Yardley was Tennessee's first black candidate for governor in 1876. Knoxville College was founded in 1875 to provide education for the city's black community.

Greek immigrants began arriving in the early 1900s. Knoxville's Greek community is known for its restaurant owners, like the Regas and Paskalis families. Jewish immigrants also contributed to the city, including jewelers and department store owners. Many people also moved to Knoxville from nearby rural areas. They often looked for jobs in factories. Many of Knoxville's leaders in the 1900s came from these rural areas.

Knoxville in the Gilded Age

A Swiss immigrant named Peter Staub built Knoxville's first opera house, Staub's Theatre, on Gay Street in 1872. This was one of the first major buildings designed by architect Joseph Baumann. He designed many important buildings in the late 1800s. The Lamar House Hotel was a popular gathering place for the city's wealthy people. It hosted fancy parties and served expensive food and drinks.

Market Square started as a place for farmers to sell goods. By the 1870s, it became a commercial and cultural center. A famous business there was Peter Kern's ice cream shop. The square also attracted street preachers, early country musicians, and political activists. Women's rights activist Lizzie Crozier French gave speeches on Market Square as early as the 1880s.

After the Civil War, Thomas William Humes became president of East Tennessee University. He got government funds for the school, allowing it to grow. In 1886, the Lawson McGhee Library was established. It became the basis of Knox County's public library system. In 1873, Knoxville started a public school system.

City expansion (1869–1917)

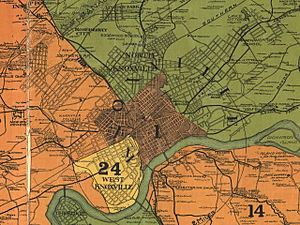

Knoxville's first big expansion after the Civil War was in 1869. It added East Knoxville, an area that had become a city in 1856. In 1883, Knoxville added Mechanicsville. This area had grown as a village for factory workers. In the 1870s and 1880s, Knoxville's streetcar system led to the rapid growth of suburbs. Neighborhoods like Fort Sanders, Fourth and Gill, Old North Knoxville, and Parkridge all started as "streetcar suburbs" during this time.

In 1888, the Fort Sanders area and the University of Tennessee campus became the City of West Knoxville. In 1889, Old North Knoxville and Fourth and Gill became the City of North Knoxville. Knoxville added both of these areas in 1897. In 1907, Parkridge and other neighborhoods became Park City. Lonsdale, a factory village, and Mountain View also became cities that year. Oakwood, which grew near the Southern Railway yard, became a city in 1913. In 1917, Knoxville added these four cities, along with Sequoyah Hills and parts of South Knoxville. This more than doubled the city's population and greatly increased its land area.

As Knoxville grew, city leaders promoted it as an industrial boom town. They wanted to attract big companies. In 1910 and 1911, two large national fairs, the Appalachian Expositions, were held at Chilhowee Park. A third fair, the National Conservation Exposition, was held in 1913. These fairs showed the economic trend of the "New South," where the South changed from farming to industry. The fairs also promoted using natural resources responsibly.

City challenges

Knoxville's fast growth in the late 1800s led to more pollution, mainly from using more coal. It also led to a rise in crime, made worse by many people moving to the city for low-paying jobs. The city had suffered serious outbreaks of diseases like cholera and smallpox. So, it created a health department in 1879 and a city hospital in 1883. Activists and business leaders also started groups to help the poor.

After World War I, the United States faced an economic downturn. Knoxville, like many cities, saw many people move there looking for work. Tensions between different racial groups increased as poor white and black people competed for jobs. Both the Ku Klux Klan and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) opened chapters in the city. On August 30, 1919, these tensions exploded in the Riot of 1919. This was the city's worst race riot.

Knoxville becomes a modern city (1920–1960)

Louis Brownlow and city government

In 1912, Knoxville changed its government system. It elected five commissioners, and one of them was chosen as mayor. After the 1917 annexations, the city struggled to provide services to the new areas. The new government was not good at handling the city's money problems. In 1923, the city voted to change its government again. A city council would be elected, and they would hire a city manager to run the city's daily business.

The first city manager hired was Louis Brownlow. He had been a successful city manager in Virginia. When Brownlow arrived in Knoxville, he was shocked by the city's condition. He later wrote that he found "something new and more disturbing" every day. There were no paved roads connecting Knoxville to other major cities. The city's water tank was leaking. The city hospital was deeply in debt and couldn't buy medicine. City Hall was dirty and disorganized.

Brownlow immediately started working to fix things. He got better loan rates and made sure all purchases were carefully checked. He also convinced the city to buy the old Tennessee School for the Deaf building to use as a new City Hall. Brownlow had some success, but he faced strong opposition, especially when he asked for a tax increase. After a less friendly city council was elected in 1926, Brownlow resigned.

Economic challenges

While Knoxville grew a lot in the late 1800s, its economy started to slow down in the early 1900s. The natural resources nearby were used up, or people didn't need them as much. The decline of railroads also hurt the city's wholesale business. Population growth also slowed.

One historian suggests that the city's leaders were too old-fashioned and didn't like change. Also, many new people from rural areas and African Americans were suspicious of government. This combination led to the city often rejecting major reform efforts. Since Knoxvillians were against tax increases, the city had to rely on borrowing money for services. More and more money went to paying off these debts, leaving little for city improvements. Older neighborhoods and downtown areas became run down. Those who could afford it moved to new suburbs.

During the Great Depression, Knoxville's six largest banks either failed or merged. Construction dropped by 70%, and unemployment tripled. African Americans were hit hardest, as businesses started hiring white workers for jobs that black workers traditionally held. The city had to pay its employees with special paper money and begged lenders to let it delay debt payments.

Federal programs and new construction

In the 1930s and early 1940s, several big federal programs helped Knoxvillians during the Depression. The Great Smoky Mountains National Park, which wealthy Knoxvillians helped create, opened in 1932. In 1933, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) was started with its main office in Knoxville. Its goal was to control floods, improve river travel, and provide electricity. During World War II, the building of Manhattan Project facilities in nearby Oak Ridge brought many federal workers to the area. This helped Knoxville's economy.

Kingston Pike saw a lot of tourism in the 1930s and 1940s. It was part of two major cross-country routes, the Dixie Highway and the Lee Highway. Traffic to the Great Smoky Mountains also led to development along Chapman Highway in South Knoxville. In the late 1920s, land was donated for McGhee Tyson Airport, named for a World War I pilot. In 1947, Knoxville replaced its streetcar system with buses. The TVA's completion of Fort Loudoun Dam in 1943 changed Knoxville's riverfront.

In 1946, a travel writer visited Knoxville and called it the "ugliest city" in America. He also made fun of its strict laws about selling alcohol and showing movies on Sunday. While Knoxvillians defended their city, his comments led to discussions about the city's appearance and laws. The rule against Sunday movies was removed in 1946. Knoxville allowed packaged alcohol sales in 1961, though it remained a debated issue for years.

Knoxville's rebirth (1960–present)

Knoxville in the 1960s

In 1960, several Knoxville College students, led by Robert Booker, held sit-ins to protest segregation at lunch counters downtown. This action led downtown department stores to desegregate. By the end of the decade, most other downtown businesses had followed. City schools also slowly desegregated during this time.

Between 1945 and 1975, the University of Tennessee's student body grew from under 3,000 to nearly 30,000. The campus expanded, and the Fort Sanders neighborhood largely became student housing. By the mid-1970s, the University of Tennessee employed over 4,000 people, boosting the city's economy. The school's popular sports teams led to the expansion of Neyland Stadium and the building of Thompson–Boling Arena.

While unemployment dropped in the 1960s, many jobs paid low wages. This slowed the growth of the city's service industry. Large parts of downtown continued to decline. Nearly half of all houses in older neighborhoods were considered in bad condition. One area was ranked very low among urban neighborhoods for its housing.

Downtown improvements

Starting in the 1950s, Knoxville tried hard to make its downtown area better. One major effort was replacing the large Market House on Market Square with a pedestrian area. The city also tried to bring shoppers back to Gay Street. But downtown stores continued to struggle. When West Town Mall opened in 1972, downtown retail collapsed. Many major stores and theaters closed by 1978.

In 1962, Knoxville added several large communities, including Fountain City, Inskip, Bearden, and West Hills. This brought many new voters into the city. In the early 1970s, Mayor Kyle Testerman and the city council created the "1990 Plan." This plan aimed to create a financial district downtown, with a mix of homes, offices, and unique shops, instead of trying to bring back large retailers.

In 1978, voters in Knoxville and Knox County again voted on combining the city and county governments. Despite support from many leaders, the idea failed. Most Knoxville voters supported it, but most Knox County voters did not.

1982 World's Fair

In 1974, a local business leader suggested hosting an international exposition in Knoxville. Mayor Testerman supported the idea, though the city council and citizens were at first unsure. A key supporter was banker Jake Butcher, who helped the city raise important funds.

To get ready for the World's Fair, major highways were widened. The old L&N rail yard along Second Creek was chosen for the fair site. Three hotel chains built large hotels downtown, expecting many visitors. The fair, called the International Energy Exposition, was open from May 1 to October 31, 1982. It attracted over 11 million visitors. Its success surprised many, including the Wall Street Journal, which had called Knoxville a "scruffy little town" and predicted the fair would fail.

While the fair made money, it left Knoxville in debt. It also did not lead to the big redevelopment that its promoters hoped for. The day after the fair closed, federal officials investigated Butcher's banks. This led to the collapse of his banking business and threatened the city's financial stability. Testerman became mayor again in 1983 and tried to restart downtown redevelopment plans.

1980s, 1990s, and 2000s

The second Testerman administration stabilized the city's finances. It started urban renewal projects in some neighborhoods. It also combined Knoxville City and Knox County schools. With help from entrepreneur Chris Whittle, Testerman created a new downtown redevelopment plan in 1987. This plan called for more improvements to Market Square and Gay Street.

Victor Ashe, Testerman's successor, continued redevelopment efforts. He focused on parks and run-down areas in East and North Knoxville. Since the town of Farragut had stopped Knoxville's westward expansion, Ashe focused on "finger" annexations. This meant adding small pieces of land at a time. Ashe made hundreds of these annexations during his 16 years as mayor, expanding the city by over 25 square miles.

Efforts to preserve historic buildings in Knoxville have grown. Many historic areas have been protected. Developers like Kristopher Kendrick and David Dewhirst have bought and restored many old buildings. This has slowly brought residents back to the downtown area. In the 2000s, Knoxville's planners focused on developing mixed neighborhoods (like the Old City). They also worked on shopping centers (like Turkey Creek) and a downtown area with unique shops, restaurants, and entertainment. These efforts have been very successful. In 2020, many Knoxville businesses closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Learning about Knoxville's history

The East Tennessee Historical Society publishes a journal with many articles about Knoxville. The Society has also published two detailed histories of Knoxville and Knox County. Other histories include Standard History of Knoxville (1900) and Knoxville (2003).

The Civil War in Knoxville is a very well-covered topic. Early accounts include diaries and books written by people who lived through the war. Modern books include Divided Loyalties: Fort Sanders and the Civil War (1963) and Lincolnites and Rebels (2006).

Knoxville's history from the Civil War to modern times is covered in books like Knoxville, Tennessee: Continuity and Change in an Appalachian City (1983). Mark Banker's Appalachians All (2010) discusses Knoxville and other East Tennessee communities.

The history of Knoxville's African American community is covered in Robert Booker's Two Hundred Years of Black Culture in Knoxville, Tennessee: 1791 to 1991 (1994). Booker's The Heat of a Red Summer: Race Mixing, Race Rioting in 1919 Knoxville (2001) describes the Riot of 1919. Merrill Proudfoot's Diary of a Sit-In (1962) tells about the 1960 Knoxville sit-ins.

Since the early 1990s, Jack Neely has written many articles about the interesting and forgotten parts of the city's history. His articles have been put into books like The Secret History of Knoxville (1995). Other books cover topics like Knoxville's Jewish community and the city's radio stations. Dr. Marcy Conway's book The Sunsphere City (2022) also talks about Knoxville's history and current culture.

The Junior League of Knoxville's Knoxville: 50 Landmarks (1976) describes historical buildings. A more detailed look at the city's architecture is in "Historic and Architectural Resources of Knox County" (1994). The National Register of Historic Places includes over 100 buildings and districts in Knoxville and Knox County.

Images for kids

| William Lucy |

| Charles Hayes |

| Cleveland Robinson |