History of Nagorno-Karabakh facts for kids

Nagorno-Karabakh is a mountainous area in the southern part of the Lesser Caucasus mountains. It's located at the eastern edge of the Armenian Highlands. The name Nagorno-Karabakh means "Mountainous Karabakh" in Russian. The word Karabakh itself comes from Persian and Turkic words meaning "black vineyard." This name was first used in the 13th and 14th centuries to describe the lowlands between the Kura and Aras rivers, and the mountains next to them.

After the Soviet Union broke apart, most of this area was controlled by the Artsakh Republic. This republic had support from Armenia but was seen by other countries as legally part of Azerbaijan. After a war in 2020, Azerbaijan took back many surrounding areas and some parts of Nagorno-Karabakh. On January 1, 2024, the Artsakh Republic officially ended.

Contents

- Ancient Times

- The Legend of Aran

- Artsakh as Part of Armenia

- Christianity and Culture

- Armenian Princedoms

- Seljuks, Mongols, and Safavids

- Armenian Melikdoms

- Karabakh Khanate

- Russian Rule

- October Revolution, 1917

- 1918-1921 Armenian-Azerbaijani Dispute

- Soviet Era, 1921–1991

- First Nagorno-Karabakh War

- 2010s

- 2023

- See also

Ancient Times

The area of Nagorno-Karabakh, between the Kura and Araxes rivers, was once home to people known as the Kura-Araxes. We don't know much about its very old history because there aren't many historical records. However, jewelry found here has the name of Adad-Nirari, a King of Assyria from around 800 BCE.

The region was first mentioned as Urtekhini in writings by Sardur II, King of Urartu, who lived from 763 to 734 BC. These writings were found in a village called Tsovk in Armenia. After that, there are no more records until the time of Rome.

Around the time of the Hellenistic period, the people living in Nagorno-Karabakh were not Armenian. They became Armenian after Armenia took control of the area. Some historians think the Armenian Orontid dynasty might have ruled Nagorno-Karabakh in the 4th century BC, but others disagree.

The Legend of Aran

Many local stories say that the two river valleys in Nagorno-Karabakh were among the first places settled by the children of Noah. An Armenian story from the 5th century CE says that a local leader named Aran was chosen by the Parthian King Vologases I to be the first governor of this region. Ancient Armenian writers say Aran was the ancestor of the people in Artsakh and the nearby province of Utik. Through his family, Aran was related to Hayk, who is considered the ancestor of all Armenians.

Artsakh as Part of Armenia

The ancient writer Strabo described "Orchistenê" (Artsakh) as the part of Armenia with the most horsemen. It's not clear exactly when Artsakh became part of Armenia. The ruins of the city of Tigranakert are found near the modern city of Aghdam. This was one of four cities built by the Armenian king Tigranes the Great around the 1st century BC. Recent digs have found parts of a fortress and many old items, similar to those found in Armenia. These discoveries show the city existed from the 1st century BC to the 13th or 14th century AD.

People living in Artsakh long ago spoke a dialect of the Armenian language. This was noted by Stepanos Siunetsi, an Armenian grammar writer from around 700 AD.

Ancient writers like Strabo and Pliny the Elder said that the Kura River was the border between Greater Armenia and Caucasian Albania. Artsakh is located south of this river. There is no clear evidence that Artsakh was part of Caucasian Albania or any other country until at least the late 4th century.

The Armenian historian Faustus of Byzantium wrote that around 370 AD, when Persia invaded Armenia, Artsakh was one of the provinces that rebelled. The Armenian military leader Mushegh Mamikonian defeated Artsakh and later took Utik back from the Caucasus Albanians, restoring the border along the Kura River.

According to the Geography by the 7th-century Armenian geographer Anania Shirakatsi, Artsakh was the 10th of 15 provinces of Armenia. It had 12 districts. However, Anania also predicted that Artsakh and nearby regions would "tear away from Armenia." This happened in 387 AD, when Armenia was divided between the Roman Empire and Persia. Artsakh, along with Utik and Paytakaran, became part of Caucasian Albania.

Christianity and Culture

Christianity began to spread in Artsakh in the early 4th century. In 469, the Kingdom of Albania became a Persian province.

In the early 5th century, Mesrop Mashtots created the Armenian alphabet. He also founded one of the first schools in Armenia at the Amaras Monastery in Artsakh. This led to a period of great cultural growth and a stronger national identity.

In 451, Armenians rebelled against Persia's attempt to force them to practice the Zoroastrian religion. Artsakh took part in this revolt, known as the Vardan war. After the rebellion was put down, many Armenians hid in Artsakh's strong fortresses and thick forests to continue fighting. This led to the Treaty of Nvarsak in 484, which confirmed Armenia's right to practice Christianity freely.

By the end of the 5th century, Artsakh and nearby Utik were united under the rule of the Aranshakhiks, led by Vachagan III. During his time, culture and science continued to grow in Artsakh. It's said that as many churches and monasteries were built as there are days in a year. In the 7th century, the Mihranids, a Persian family, took over from the Aranshakhiks. They became Christian and adopted Armenian culture.

In the 7th and 8th centuries, a unique Christian culture developed. Monasteries like Amaras, Orek, Katarovank, and Djrvshtik became very important throughout Armenia.

Armenian Princedoms

From the early 9th century, the Armenian princely families of Khachen and Dizak grew stronger. In 821, the Amaras Monastery was attacked by Arab invaders. It was later rebuilt by Yesai Arranshahik, the ruler of Dizak, who fought against the invaders. The prince of Khachen, Sahl Smbatean, also fought Arab invaders starting in 822.

During the medieval period, architecture flourished, especially religious buildings. Examples include the Church of Hovanes Mkrtich at the Gandzasar Monastery, built between 1216 and 1260. Other masterpieces of Armenian architecture are the Dadivank Monastery Cathedral Church (1214) and the Gtichavank cathedral (1241–1248).

Seljuks, Mongols, and Safavids

In the 11th century, the Seljuk invasion swept across the Middle East, including the Transcaucasia region. Nomadic Oghuz tribes, who came with this invasion, became a big part of the ancestry of modern Azerbaijanis. From then until the early 20th century, these tribes used mountainous Karabakh as their summer pastures, staying there for several warmer months.

In the 12th and 13th centuries, the Armenian Zakarian dynasty briefly controlled Khachen.

For about 30-40 years in the 13th century, the Tatar and Mongols conquered Transcaucasia. The efforts of the Artsakh-Khachen prince Hasan-Jalal helped save the land from complete destruction. However, after his death in 1261, Khachen came under Tatar and Mongol rule. The situation worsened in the 14th century when other Turkic groups, the Qara Koyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu, took over.

Nomadic groups continued to live in Artsakh and the eastern plains during this time. The large area between the Kura and Araxes rivers got its Turkic name Karabakh (meaning "black garden"). Artsakh became known as its mountainous part, or Nagorno-Karabakh in Soviet times.

The name Karabakh was first mentioned in the 13th and 14th centuries in Georgian and Persian writings. It became common after the Mongols conquered the region in the 1230s.

In the early 16th century, the Safavid Empire conquered Karabakh. They created Safavid Karabakh, which included some nearby areas, and made the city of Ganja its center. During this time, Christian Armenians in Karabakh had to pay higher taxes.

Over centuries, Armenians living under Muslim leaders adopted some elements of Persian-Turkic Muslim culture, such as language, names, and music.

Armenian Melikdoms

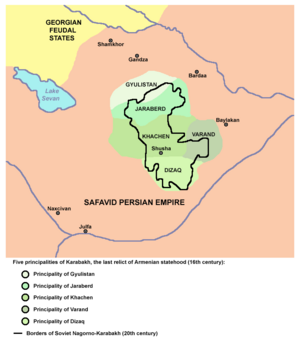

The princedom of Khachen existed until the 16th–17th centuries, then it split into five smaller princedoms, called "melikdoms":

- Giulistan or Talish melikdom

- Dzraberd or Charaberd melikdom

- Khachen melikdom

- Varanda melikdom

- Dizak melikdom

These melikdoms were known as khamsa, which means "five" in Arabic.

Even though they were under the rule of Safavid Persia, the Armenian meliks had a lot of freedom in Upper Karabakh. They kept a kind of self-rule for four centuries. In the early 18th century, the Persian ruler Nadir Shah took Karabakh away from the Ganja Khanate and put it directly under his control. He also gave the Armenian meliks command over neighboring areas because they had helped defeat the Ottoman Turks in the 1720s.

Some historians say that only the melik-Hasan-Jalalyans of Khachen were originally from Karabakh. However, modern scholars like Robert Hewsen and Cyril Toumanoff have shown that all these meliks were descendants of the House of Khachen.

The idea of Armenian independence in Karabakh from Persia first appeared in the late 17th century, thanks to the meliks. Armenians tried both armed struggle and diplomacy, seeking help from Europe and then Russia. Leaders like Israel Ori and Catholicos Yesai Jalalian led the people.

In the 18th century, Persia faced political problems, and its unity was threatened. Both Turkey and Russia hoped to gain territory if Persia broke apart. Russia sought support from Armenians and Georgians.

In 1722, Peter the Great's war with Persia began. Russian forces quickly took Derbent and Baku. Armenians, encouraged by Russia, joined with Georgia and formed an army in Karabakh. However, Russia did not provide the promised help. Instead, Peter the Great advised Armenians to move to areas where Russian power was established. Russia then signed a treaty with Turkey in 1724, giving Turkey control over Transcaucasia.

Ottoman troops invaded that year. The Armenian people of Karabakh, led by their meliks, fought for their independence but did not receive Russian support. Still, Peter the Great's actions encouraged the Armenians to continue their fight.

In the 1720s, the Armenian army in Karabakh gathered in three military camps. These camps, known as Skhnakhs, were strongholds. The Armenian army was a people's army, with military leaders and the Catholicos of Gandsasar having great influence. The meliks shared their power with other commanders, and everyone had equal rights in military councils. This Armenian force resisted the Ottoman army for a long time.

In 1733, Armenians, encouraged by Nadir Shah of Persia, attacked and defeated Ottoman troops in Karabakh. After this, the area's previous status was restored. Nadir Shah then freed the Khamsa meliks from the Ganja khans and appointed Avan, melik Dizak, as their ruler, giving him the title of khan. However, Avan Khan soon died.

Karabakh Khanate

In 1747, a Turkic ruler named Panah Ali Khan Javanshir, who was a skilled warrior, returned to his homeland in Karabakh. He had been unhappy with Nader Shah. Panah Ali declared himself a ruler (khan) and was soon recognized in most of the region. The new ruler of Persia, Adil Shah, officially recognized Panah Ali as the Khan of Karabakh.

Melik Shahnazar II of Varanda, who had disagreements with other meliks, was the first to accept Panakh Khan's rule. Panakh Khan built the fortress of Shusha in a location suggested by Melik Shahnazar and made it the capital of the Karabakh khanate.

Agha Mohammad Khan of the Qajar dynasty later brought the region back under strong Iranian control. However, he was killed a few years later, leading to more political problems.

The meliks did not want to accept the new situation. They hoped for help from the Russians and sent letters to Catherine II of Russia. But the khan, Ibrahim Khalil Khan, learned of this. In 1785, he arrested some meliks, attacked Gandzasar monastery, and imprisoned its Catholicos. This led to the final collapse of the Khamsa melikdoms.

Ibrahim Khalil Khan made the Karabakh khanate a semi-independent princedom, which only formally recognized Persian rule.

In 1797, Karabakh was invaded by the armies of Persian shah Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar. Shusha was under attack, but Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar was killed by his own servants. In 1805, Ibrahim-khan signed the Treaty of Kurakchay with Imperial Russia. Under this treaty, the Karabakh Khanate became a protectorate of Russia. However, the next year, Ibrahim-Khalil was killed by the Russian commander in Shusha, who suspected him of trying to escape to Persia. Russia then appointed Ibrahim-Khalil's son, Mekhti-Gulu, as his successor.

In 1813, the Karabakh Khanate, Georgia, and Dagestan became part of Imperial Russia through the Treaty of Gulistan. The rest of Transcaucasia joined the Empire in 1828 under the Treaty of Turkmenchay, after two wars between Russia and Persia. In 1822, Mekhti-khan fled to Persia and returned in 1826 with Persian armies to invade Karabakh. But they could not take Shusha, which was strongly defended by Russians and Armenians. The Karabakh Khanate was then dissolved, and the area became part of the Russian Empire.

Russian Rule

The Russian Empire took control of the Karabakh Khanate in 1806. Its power was solidified after the Treaty of Gulistan in 1813 and the Treaty of Turkmenchay in 1828. Persia recognized that Karabakh and other areas were now part of Russia.

Russia dissolved the Karabakh khanate in 1822. A survey from 1823 showed that all Armenians in Karabakh lived in the highland part, where the five traditional Armenian princedoms were. They made up the majority of the population in those lands. For example, the district of Khachen had twelve Armenian villages and no Muslim villages.

During the 19th century, Shusha became a very important city in Transcaucasia. By 1900, it was the fifth-largest city in the region, with a theater and printing houses. Carpet making and trade were especially well-developed. According to a Russian census in 1823, Shusha had more Azerbaijani families (72.5%) than Armenian families (27.5%). However, the 1897 census showed that 56.5% of its 25,656 inhabitants were Armenian, and 43.2% were Azerbaijani.

During the first Russian revolution in 1905, there were violent clashes between Armenians and Azerbaijanis.

October Revolution, 1917

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, a temporary Russian government was set up. Later, the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic was formed, and Karabakh became a part of it.

After the October Revolution, a local government called the National Council of Baku was established in Baku, led by an Armenian named Stepan Shaumyan.

Armenians held a national congress in October 1917. Muslim Azerbaijani National Councils also created a defense plan and a local government structure for Transcaucasia.

1918-1921 Armenian-Azerbaijani Dispute

From 1918 to 1919, Nagorno-Karabakh was mostly controlled by the local Armenian Karabakh Council, as most of its people were Armenian. Azerbaijan tried many times to take control of the region. The British governor of Baku appointed Khosrov bey Sultanov as governor-general of Karabakh and Zangezur, planning to make Karabakh part of Azerbaijan. In 1919, under threat of violence, the Karabakh Council agreed to temporarily recognize Azerbaijan's rule until the status could be decided at the Paris Peace Conference.

Independent States, May 1918

In May 1918, the Transcaucasian Republic split into three separate countries:

Both Armenia and Azerbaijan claimed Nagorno-Karabakh and had strong reasons for doing so.

Armenia saw Nagorno-Karabakh as its natural border, the easternmost part of the Armenian Plateau. Losing it would break the physical connection of Armenia. Armenia also pointed to Karabakh's historical ties as a place where Armenian statehood and nationalism grew. Armenians were the majority in the mountainous parts of Karabakh. Armenia also saw Karabakh as a barrier between Azerbaijan and Turkey.

Azerbaijan also used history to support its claim. It argued that Nagorno-Karabakh had been part of Muslim khanates, even with some self-rule. Azerbaijanis and Kurds made up a significant minority in the heart of Nagorno-Karabakh. Azerbaijan believed that separating the mountains and plains of Karabakh would harm the many Azerbaijani nomads who moved between them. Economically, Karabakh was connected to Azerbaijan, with most major roads leading east to Baku.

Ethnic and Religious Tension, March 1918

In March 1918, tensions between Armenians and Azerbaijanis grew, and conflict began in Baku. There were armed clashes, and many Azerbaijanis and other Muslims were killed in what became known as the March Days. At the same time, there was heavy fighting between the Baku Commune and the advancing Ottoman army.

The government of Azerbaijan declared that Karabakh was now part of the newly formed Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. However, Nagorno-Karabakh and Zangezur refused to recognize Azerbaijan's authority. Armenian local councils took power and led the fight against Azerbaijan.

Armenian "People's Government," July 1918

On July 22, 1918, the First Congress of Armenians in Karabakh declared Nagorno-Karabakh independent. They elected a National Council and a people's government. This government had five administrators for different areas like foreign affairs, military, and finances.

In September, the People's Government was renamed the Armenian National Council of Karabakh, but its structure remained similar. On July 24, they adopted a declaration outlining the goals of their new government.

Armistice of Mudros, October 1918

On October 31, 1918, the Ottoman Empire lost World War I, and its troops left Transcaucasia. British forces arrived in December and took control of the area.

British Mission

The Azerbaijani government tried to take Nagorno-Karabakh with British help. The British command wanted to include Nagorno-Karabakh into Azerbaijan even before the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. They wanted to control Baku oil and separate Transcaucasia from Russia, with Azerbaijan acting as a barrier against Soviet influence.

The Allied powers seemed to favor Azerbaijan. The Karabakh problem was delayed, hoping that the situation would become better for Azerbaijan, possibly by changing the ethnic makeup of Nagorno-Karabakh.

On January 15, 1919, the Azerbaijani government, with British approval, appointed Khosrov bey Sultanov as governor-general of Nagorno-Karabakh. They demanded that the Karabakhian National Council recognize Azerbaijan's power. On February 19, 1919, the 4th Congress of Armenians in Karabakh strongly rejected this demand. They stated that the Armenian people of Karabakh would never accept Azerbaijani rule.

The British mission issued a statement saying that Sultanov was appointed as a temporary governor and that the final decision on the territories would be made at a Peace Conference.

The National Council of Karabakh responded that they could not accept being dependent on Azerbaijan due to past violence. They believed that Armenian Karabakh was not under any state's control until the Peace Conference decided. They asked for a British general-governor instead.

However, despite these protests, the British continued to help Azerbaijan take control of Armenian Karabakh. The British commander in Baku, Colonel Digby Shuttleworth, warned the Karabakhian people that any actions against Azerbaijan would be seen as actions against England.

Shusha, April 1919

When threats and force didn't work, Shuttleworth personally came to Shusha in April 1919 to make the National Council of Karabakh recognize Azerbaijan's power. On April 23, the Fifth Congress in Shusha rejected his demands.

Rejected by the Congress, Sultanov decided to use force. Almost the entire Azerbaijani army gathered at the borders of Nagorno-Karabakh. In early June, Sultanov tried to block the Armenian parts of Shusha, attacked Armenian positions, and organized attacks on Armenian villages. Nomads led by Sultanov's brother killed 580 Armenians in the village of Gayballu. British troops left Nagorno-Karabakh to give Azerbaijani troops a free hand.

The Sixth Congress of Karabakh Armenians was supposed to discuss relations between Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan before the Paris Peace Conference. However, the English mission and Azerbaijani government arrived after the Congress had finished. A commission found that Karabakh could not defend its independence in a war. So, under threat of attack from Azerbaijan, the Congress felt forced to start negotiations.

Peace Conference, August 1919

To gain time to gather its forces, the Congress met on August 13, 1919, and reached an agreement on August 22. Under this agreement, Nagorno-Karabakh considered itself within the borders of the Azerbaijani Republic until the problem was solved at the Peace Conference in Paris. However, the Azerbaijani armies were in peacetime status. Azerbaijan could not send its army into the area without the National Council's permission. Disarming the population was also stopped until the peace conference.

In February, Azerbaijan began to gather military and irregular groups around Karabakh.

1920–1921

On February 19, 1920, Sultanov demanded that the National Council of Karabakh Armenians "urgently... solve the question of the final incorporation of Karabakh into Azerbaijan."

The Eighth Congress of Karabakh Armenians, from February 23 to March 4, 1920, rejected Sultanov's demand. The Congress accused Sultanov of breaking the peace agreement many times, sending armies into Karabakh without permission, and organizing murders of Armenians.

However, the wishes of the Azerbaijani population of Karabakh were also often ignored by Armenian inhabitants, who, according to some, did not have the right to represent the will of the entire region's population.

The Congress decided to inform the Allied representatives and the provisional governor-general that if these events happened again, Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh would use "appropriate means for defense."

Nagorno-Karabakh War, 1920

In March–April 1920, there was a short war between Azerbaijan and Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh. It started on March 22, when Armenian forces attacked Askeran and Khankendi unexpectedly. The Armenians thought Azerbaijanis would be celebrating Nowruz (a holiday) and wouldn't be ready to defend themselves. However, their attack on the Azerbaijani garrison in Shusha failed.

In response to the attack, Azerbaijanis burned down the Armenian part of Shusha and attacked its people.

The attack and expulsion of Shusha's Armenian population was the biggest escalation of the conflict so far. Armenian sources report different numbers of casualties, from 500 to 35,000, with most saying 20,000–30,000. Estimates for burned homes range from two thousand to seven thousand. According to the Greater Soviet Encyclopedia, 20% of Nagorno-Karabakh's population was lost, which means about 30,000 people, mostly Armenians, who made up 94% of the area's population.

The Paris Peace Conference didn't solve the land disputes in Transcaucasia. So, Armenia decided to free Karabakh from Azerbaijan. An uprising in Karabakh, planned for the Azerbaijani Novruz celebrations, failed because of poor planning. Azerbaijani troops remained in Shushi and nearby Khankend, and an attack followed in Shusha. Azerbaijani soldiers and residents burned and looted half of the city.

After the uprising, the Armenian government ordered its forces to help the Karabakh rebels. Azerbaijan moved its army west to crush the Armenian resistance, even with the 11th Red Army of Bolshevik Russia approaching from the north. By the time Azerbaijan became Soviet, Azerbaijani forces still controlled the central cities of Karabakh, Shusha and Khankend. The surrounding areas were controlled by local fighters and Armenian army help. The Bolshevik army eventually defeated the Armenian army and drove them from the region. Armenians in Karabakh felt safer returning to Russian control.

Armenian Declaration, April 1920

In April 1920, the Ninth Congress of Karabakh Armenians declared Nagorno-Karabakh part of Armenia. They stated that the agreement with Azerbaijan was broken due to Azerbaijani attacks on Armenian civilians.

However, with direct involvement from Russian troops, Azerbaijan regained control of the area.

Soviet Era, 1921–1991

On July 4, 1921, a meeting of the Communist Party decided to make Karabakh part of Armenia. However, the next day, Joseph Stalin stepped in and decided to keep Karabakh in Soviet Azerbaijan. This decision was made without asking the local people. As a result, the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) was created within the Azerbaijan SSR in 1923. Many Armenians still blame Stalin for this decision, saying it went against their national interests.

For 65 years, Armenians in the NKAO felt limited by Azerbaijan. They were unhappy that Azerbaijan cut ties between the region and Armenia. They also felt that Azerbaijan was trying to reduce Armenian culture, encourage Azeri settlement, push Armenians out of the NKAO, and ignore their economic needs. The 1979 census showed that out of 162,200 people in the NKAO, 123,100 were Armenians (75.9%) and 37,300 were Azerbaijanis (22.9%). Armenians compared this to 1923 data, which showed 94% Armenian. They also noted that 85 Armenian villages (30%) had disappeared by 1980, while no Azerbaijani villages had. Armenians accused the Azerbaijani government of a "purposeful policy of discrimination." They believed Baku wanted to remove all Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh.

On the other hand, Azerbaijani residents of the NKAO complained of discrimination by the Armenian majority and economic problems. While the NKAO's economy was better than Azerbaijan's overall, it was worse off than Armenia.

When the Soviet Union began to break up in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the issue of Nagorno-Karabakh came up again. On February 20, 1988, the NKAO local government looked at the results of an unofficial vote, a petition signed by 80,000 people, asking for Nagorno-Karabakh to join Armenia. Based on this, the NKAO government asked the Soviet Union, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to allow Karabakh to leave Azerbaijan and join Armenia.

This angered the neighboring Azerbaijani population, who started gathering to "put things in order" in Nagorno-Karabakh. On February 24, 1988, a clash happened near Askeran, on the road between Stepanakert and Aghdam. About 50 Armenians were wounded, and two Azerbaijanis were killed. As a result, an attack against Armenian residents began in the city of Sumgait, where many Azerbaijani refugees lived. This attack lasted three days. The exact number of deaths is debated, but the US Library of Congress reported over 100 Armenian victims.

Similar attacks on Azerbaijanis happened in Armenian towns like Spitak and Gugark. Many refugees left both Armenia and Azerbaijan as these attacks against minority groups began. In late 1989, growing conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh led Moscow to give Azerbaijani authorities more control over the region. However, this backfired when the Armenian Soviet Republic and the Nagorno-Karabakh National Council declared that Nagorno-Karabakh was uniting with Armenia. In mid-January 1990, Azerbaijani protesters in Baku attacked the remaining Armenians there. Moscow only intervened after almost no Armenian population was left in Baku. They sent army troops, who stopped the Azerbaijan Popular Front and installed Ayaz Mutallibov as president.

In a December 1991 vote, which most local Azerbaijanis did not participate in, the Armenian population, still a majority in Nagorno-Karabakh, voted to create an independent state. However, the Soviet Constitution only allowed the fifteen Soviet Republics to vote for independence, and Nagorno-Karabakh was not one of them. A Soviet proposal for more self-rule for Nagorno-Karabakh within Azerbaijan did not satisfy either side, which led to the war between Armenia-backed Nagorno-Karabakh and Azerbaijan.

First Nagorno-Karabakh War

The conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh grew worse after both Armenia and Azerbaijan became independent from the Soviet Union in 1991. By the end of 1993, the war had caused thousands of deaths and created hundreds of thousands of refugees on both sides. The UN estimated that almost one million Azerbaijani refugees and displaced people were in Azerbaijan by late 1993. Russia, Kazakhstan, Iran, and organizations like the UN tried to mediate, but peace talks often failed, and cease-fires broke down.

In mid-1993, Azerbaijani President Əliyev tried to negotiate directly with the Karabakh Armenians. His efforts led to several longer cease-fires in Nagorno-Karabakh. However, outside the region, Armenians took control of large parts of southwestern Azerbaijan near the Iranian border in August and October 1993. Iran and Turkey warned the Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians to stop their attacks that threatened to spill into other countries. The Armenians said they were pushing back Azerbaijani forces to protect Nagorno-Karabakh from shelling.

In 1993, the UN Security Council called for Armenian forces to stop their attacks and leave several Azerbaijani regions. In September 1993, Turkey increased its forces near its border with Armenia and warned Armenia to withdraw its troops from Azerbaijan immediately. At the same time, Iran conducted military exercises near the Nakhichevan Autonomous Republic, which was seen as a warning to Armenia. Iran suggested creating a 20-kilometer security zone along the Iranian-Azerbaijani border to protect Azerbaijanis. Iran also helped provide shelter and food for up to 200,000 Azerbaijanis fleeing the fighting.

Fighting continued into early 1994. Azerbaijani forces reportedly won some battles and regained some lost territory. In January 1994, Əliyev promised that occupied land would be freed, and Azerbaijani refugees would return home. At that point, Armenian forces controlled about 14% of the area recognized as Azerbaijan, with Nagorno-Karabakh itself making up 5%.

However, in the first three months of 1994, the Nagorno-Karabakh Defense Army launched a new offensive. They captured more areas, creating a wider safety zone around Nagorno-Karabakh. By May 1994, Armenians controlled 20% of Azerbaijan's territory. At this point, the Government of Azerbaijan for the first time recognized Nagorno-Karabakh as a third party in the war and began direct talks with Karabakh authorities. As a result, a cease-fire was reached on May 12, 1994, through Russian negotiations. This cease-fire lasted until the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war.

As a result of the first Nagorno-Karabakh war, Azerbaijanis were forced out of Nagorno-Karabakh and nearby areas. With Soviet/Russian military support, Azerbaijanis forced tens of thousands of Armenians out of the Shahumyan region. Armenians kept control of the Soviet-era autonomous region and a strip of land called the Lachin corridor, which connected it to Armenia. They also controlled seven surrounding districts of Azerbaijan. The Shahumyan region remained under Azerbaijan's control.

2010s

On May 23, 2010, people in the territory voted to elect the state's parliament. More than 70 international observers were present.

2023

On March 5, three Armenian police officers and two Azerbaijani soldiers were killed during border clashes near the Lachin Corridor. Both sides blamed each other. On March 25, Russia accused Azerbaijan of breaking the 2020 cease-fire agreement. This happened after Azerbaijani forces crossed the Line of Contact in Artsakh and took control of dirt roads near the Lachin corridor.

On July 11, Azerbaijan temporarily closed the Lachin corridor, the only road between Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh. They claimed there was smuggling by the Armenian Red Cross Society. The corridor was reopened on July 17 to allow the Red Cross to move patients from Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia.

On September 9, Samvel Shahramanyan was elected president of the territory in a 22-1 vote.

On September 19, Azerbaijan launched an attack on Nagorno-Karabakh. They blamed Armenian groups for an incident where four Azerbaijani police officers and two civilians were killed by mine explosions. Azerbaijan demanded that Armenian forces leave the region and that the Artsakh government dissolve itself.

The next day, September 20, Armenian forces in Nagorno-Karabakh surrendered and agreed to a Russian cease-fire proposal. Azerbaijan then called for the "total surrender" of ethnic Armenian forces and ordered the Artsakh government to dissolve itself.

Peace talks between Azerbaijan and the separatists were set for the next day in Yevlakh. Russian peacekeepers helped coordinate the cease-fire. After the surrender, thousands of Artsakh residents gathered at Stepanakert Airport, seeking evacuation.

On September 21, delegates from Azerbaijan and Artsakh met in Yevlakh. No formal agreement was made after two hours of talks.

The Artsakh government announced on September 24 that most of its people would leave after Azerbaijan took control. Armenia confirmed that 1,050 refugees from Artsakh had arrived. The number of refugees fleeing to Armenia reached 6,500 by the next day.

On September 29, Samvel Shahramanyan, the president of the breakaway Artsakh Republic, signed a paper to dissolve all state institutions of Artsakh starting in 2024.

By October 3, the number of refugees fleeing Artsakh to Armenia reached 100,617, which was most of the region's population. Davit Ishkhanyan and three former presidents of Artsakh were detained by Azerbaijan's State Security Service and taken to Baku.

|

See also

- Demographics of the Republic of Artsakh

- List of massacres in Azerbaijan

- Republic of Artsakh

- Timeline of Artsakh history