History of Phoenix, Arizona facts for kids

The history of Phoenix, Arizona, stretches back thousands of years! It started with ancient people called paleo-Indians who hunted mammoths in the Salt River Valley around 7,000 BC. When their prey moved away, they followed. Later, other nomadic tribes, called archaic Indians, came to the area, mostly from Mexico and California.

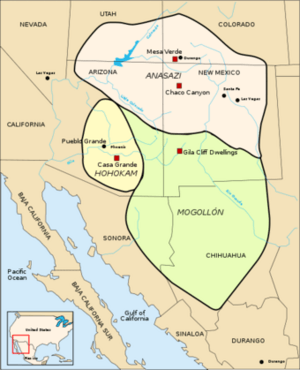

Around 1,000 BC, farming began to change things, especially with the arrival of corn. This led to the rise of the Hohokam civilization. The Hohokam settled here around 1 AD. Over 500 years, they built an amazing system of canals that helped farming grow. But for reasons still unknown, they suddenly disappeared by 1450. When the first Europeans arrived in the early 1500s, the main Native American groups living here were the O'odham and Sobaipuri tribes.

The first European explorers were Spanish, but they mostly settled in Tucson and the southern parts of Arizona before 1800. American settlers began moving into central Arizona in the early 1800s. The city of Phoenix started when these settlers moved south, and a military outpost was set up to the east.

The town of Phoenix was founded in 1867 and became an official city in 1881. It was an important farming area that relied on large irrigation systems. Before World War II, Phoenix's economy was known for the "Five C's": cotton, citrus, cattle, climate, and copper. The city also became a popular spot for winter tourists. After World War II, Phoenix grew much faster. Many soldiers who trained in the area came back with their families. The invention of air conditioning in the 1950s made the hot summers much more comfortable, attracting even more people and new industries, especially high-tech companies.

Phoenix has been one of the fastest-growing cities in the U.S. for decades. It is now the fifth largest city in the United States by population. However, in June 2023, Arizona decided to stop new housing developments in the Phoenix area that only use groundwater. This was due to concerns about water supply and climate change.

Contents

Native American History in Phoenix

Early Hunters and Gatherers

The first people in the desert southwest, including the Phoenix area, were called Paleo-Indians. They were hunters and gatherers. The word "paleo" means "ancient." They hunted huge animals like mammoths and giant bison. Evidence of these animals has been found in the Salt River Valley. Around 9,000 BC, these ancient hunters followed their prey eastward and left the area.

After the Paleo-Indians, other groups called archaic Indians moved into the American Southwest. This period lasted from about 7,000 BC until the start of the Christian era. These groups were small bands of hunters and gatherers who traveled around for thousands of years. About 3,000 years ago, their way of life began to change. They started farming, especially after corn was introduced. As farming grew, different cultures developed. From these farming cultures, a tribe known as the Hohokam emerged.

The Hohokam Civilization

Around the beginning of the Common Era, a group of archaic Indians moved north from Mexico. They brought with them farming skills, different from the hunter-gatherer ways of other tribes. Evidence of this culture has been found in the Tucson area. This group eventually became the Hohokam people. They settled in the Salt River basin around 1 AD.

The Hohokam people lived in the land that would become Phoenix for over 2,000 years. "Hohokam" is a name given to them by modern people. It comes from a Pima Indian word meaning "those who have gone."

Scientists divide the Hohokam's time in the valley into five periods. The earliest was the Pioneer Period (1–700 AD). During this time, they lived in shallow pit houses. By the end of this period, they started using canals for farming and making decorated pottery. Next was the Colonial Period (c. 700 – 900 AD). The irrigation system grew, and communities became larger. They started creating rock art and building ballcourts.

The Sedentary Period (900 to 1150 AD) saw even more growth in settlements and canals. They began building platform mounds and had more ballcourts in larger towns. The final period, the Classic Period, lasted from about 1150 AD until 1450 AD. During this time, there were fewer villages, but the ones that remained became much larger.

The Hohokam built about 135 miles (217 km) of irrigation canals. These canals made the desert land suitable for farming. Some of their ancient canal paths are still used today for modern canals like the Arizona Canal. Their irrigation system helped the Hohokam culture spread throughout the valley. By 1300 AD, the Hohokam were the largest group of people in the prehistoric Southwest. This was the biggest area of land irrigated in ancient times in North or South America, maybe even the world!

The Hohokam also traded a lot with nearby groups like the Anasazi and Mogollon. They even traded with distant civilizations like the Aztecs in Mexico. It's believed that a Hohokam person saw a very bright supernova in 1006 CE. They might have drawn it as a petroglyph (rock carving) in the White Tank Mountain Regional Park west of Phoenix. If true, this is the only known Native American drawing of that supernova.

Around the mid-1400s, the Hohokam culture suddenly disappeared from the area. People think this might have been because of long droughts and severe floods.

Modern Native American Tribes

After the Hohokam disappeared, groups of Akimel O'odham (also known as Pima), Tohono O'odham, and Maricopa tribes began to use the area. Parts of the Yavapai and Apache tribes were also present.

The O'odham people are thought to be related to the Sobaipuri tribe, who might have been descendants of the Hohokam. The two O'odham groups were the Akimel (river people) and Tohono (desert people). The Akimel O'odham were the main Native American group in the area. They lived in small villages and had their own well-developed irrigation systems along the Gila River Valley. They grew crops like corn, beans, squash, cotton, and tobacco. They were mostly peaceful and teamed up with the Maricopa tribe to protect themselves from the Yuma and Apache tribes.

The Tohono O'odham also lived in the region, but mostly to the south of the Pima, stretching to the Mexican border. They were originally called Papago by European settlers. The Tohono O'odham lived in small settlements and were seasonal farmers. They used rainwater for their crops, unlike the Akimel who used large-scale irrigation. They grew corn, beans, squash, and melons. They also gathered native plants like saguaro fruits and hunted deer, rabbit, and javelina.

The Maricopa people are part of the larger Yuma group. They moved east from the Colorado and Gila Rivers in the early 1800s. They settled among the Akimel O'odham communities.

The Salt River's changing water levels and its difficulty for boats meant that stable communities couldn't be built there until the United States took control of the area.

European Explorers Arrive

Spanish explorers probably traveled through the Phoenix area in the 1500s. They wrote about their journeys. They also brought European diseases like smallpox and measles. These diseases badly affected Native American tribes who had no protection against them. The Spanish set up a mission in the Tucson area but didn't build any settlements near Phoenix.

When the Mexican–American War ended in 1848, much of northern Mexico became part of the United States. The Phoenix area became part of the New Mexico Territory. In 1853, with the Gadsden Purchase, the U.S. promised to respect all land rights, including those of the O'odham. The O'odham later gained full constitutional rights.

During the American Civil War, both the North and South claimed the Salt River and Gila River Valleys. The South officially claimed Confederate Arizona in 1862. The North claimed the Salt River Valley as part of the Arizona Territory in 1863. Even though both sides claimed the area, the Confederates didn't try to control it. One reason Fort McDowell was built was to help the North keep control. However, since the Phoenix area had no military importance, it wasn't fought over during the war.

The Founding of Phoenix

In 1863, the mining town of Wickenburg was the first settlement in what is now Maricopa County. This was northwest of modern Phoenix.

After the Civil War, settlers from the north and east began moving into the Valley of the Sun. The U.S. Army set up Fort McDowell in 1865 to deal with Native American uprisings. To get hay for their horses, the fort created a camp on the south side of the Salt River in 1866. This was the first non-Native American settlement in the valley. Other nearby settlements later formed and merged to become the city of Tempe, but Phoenix was incorporated first.

The story of Phoenix truly begins with Jack Swilling. In November 1867, he visited the fort's camp and realized how good the Salt River Valley was for farming. He was inspired by the old Hohokam canals and started the Swilling Irrigating and Canal Company. Their goal was to build irrigation canals and develop the valley for farming. The next month, Swilling led 17 miners back to the valley, and they began building the canals.

No one knows for sure who named the new community. But stories say Darrell Duppa suggested the name Phoenix. Swilling had wanted to name it "Stonewall." Duppa thought of Phoenix because the town was rising again from the ruins of the Hohokam civilization, just like the mythical bird that rises from ashes. By January 1868, the name Phoenix was already being used.

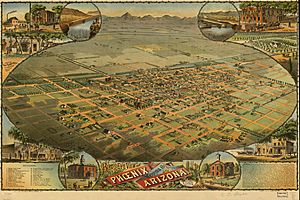

The Yavapai County Board of Supervisors officially recognized Phoenix on May 4, 1868. They created an election area for the new town. The first post office opened on June 15, 1868, in Swilling's home, with Swilling as the postmaster. As more people moved in (240 by 1870), a town site needed to be chosen. On October 20, 1870, residents met to decide where to put the town. There was a big debate between Swilling's original settlement and a new site to the west. The western site was chosen, and a 320-acre (1.3 km²) plot of land was bought in what is now downtown Phoenix.

On February 14, 1871, Anson P.K. Safford, the Governor, created Maricopa County by dividing Yavapai County. He named Phoenix the county seat, but voters had to approve it. In May 1871, Phoenix was officially chosen as the county seat. The town's first government had three commissioners.

In 1870, land lots were sold for about $48 each. The first church and store opened in 1871. The first public school class was held on September 5, 1872, in the county building. By October 1873, a small school was finished on Center Street (now Central Avenue).

By 1875, Phoenix had a telegraph office, sixteen saloons, and four dance halls. The town's government needed to change. On October 20, 1875, an election was held to choose three village trustees and other officials. The first bank opened in 1878. By 1880, Phoenix's population was 2,453.

Phoenix Becomes a City (1881)

By 1881, Phoenix had grown so much that its old village government wasn't enough. The Territorial Legislature passed "The Phoenix Charter Bill." This bill officially made Phoenix a city with a mayor-council government. Governor John C. Fremont signed the bill on February 25, 1881. Phoenix had about 2,500 people then. On May 3, 1881, Phoenix held its first city election. Judge John T. Alsap became the city's first mayor.

As Phoenix grew, so did its services. A public health department was created in the early 1880s after smallpox outbreaks. After two serious fires, a volunteer fire department was started, which led to a public water system in 1887. Other new services in this decade included a private gas lighting company (1886), a telephone company (1886), a mule-drawn streetcar system (1887), and electric power (1888).

The arrival of the railroad in the 1880s changed Phoenix's economy. A train line connected Maricopa to Tempe in 1887. Goods could now come into the city by train instead of wagons. Phoenix became a major trade center, sending its products to markets across the country. The Phoenix Chamber of Commerce was formed in 1888. City offices moved into the new City Hall in 1888. When Phoenix became the territorial capital in 1889, the temporary capital offices were also in City Hall.

The Arizona Republic newspaper became a daily paper in 1890. In 1891, Phoenix had its biggest flood ever. In 1892, the Phoenix Sewer and Drainage Department was created. The Phoenix Street Railway changed its mule-drawn streetcars to electric ones in 1893. Streetcar service continued until a fire in 1947. Also in 1893, a law was passed that allowed Phoenix to add nearby land to the city if the residents agreed. This started a process of growth that continues today. Phoenix grew from its original 0.5 square miles to over 2 square miles by 1900. On March 12, 1895, the Santa Fe, Prescott and Phoenix Railway brought its first train to Phoenix, connecting it to northern Arizona. This extra railroad helped the capital city's economy grow even faster. In 1895, Phoenix Union High School opened with 90 students.

Phoenix from 1900 to 1940

By 1900, Phoenix's population was 5,554. On February 25, 1901, Governor Murphy opened the permanent state Capitol building. It cost $130,000 to build. The Phoenix City Council approved a tax to build a public library. This helped the city get a donation from Andrew Carnegie for a library building. The Carnegie Free Library opened in 1908.

Phoenix's warm, dry weather attracted many people with tuberculosis. At that time, rest in a dry climate was the only cure for this lung disease. The Sisters of Mercy opened St. Joseph's Hospital in 1895, with rooms for tuberculosis patients. In 1910, the sisters opened Arizona's first nursing school. Today, St. Joseph's Hospital is still run by the Sisters of Mercy.

In 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt signed the National Reclamation Act. This law allowed dams to be built on western rivers for water and power. Phoenix residents quickly formed the Salt River Valley Water Users' Association in 1903 to manage water and power. This group still exists today as part of the Salt River Project. Construction on the Theodore Roosevelt Dam began in 1906. It was the first dam built under the new law to provide both water and electricity. On May 18, 1911, former President Roosevelt himself dedicated the dam. It was the largest masonry dam in the world and created new lakes.

On February 14, 1912, under President William Howard Taft, Phoenix became the capital of the newly formed state of Arizona. Phoenix was chosen as the capital because of its central location. It was smaller than Tucson at the time, but it grew to become the state's largest city in the next few decades.

In 1913, Phoenix adopted a new type of government called council-manager. This made it one of the first cities in the U.S. to use this system. After becoming a state capital, Phoenix grew quickly. By 1920, its population was 29,053. In 1920, Phoenix built its first skyscraper, the Heard Building. In 1928, Scenic Airways, Inc. bought land for an airport in Phoenix and named it Sky Harbor. It officially opened in 1929.

On March 4, 1930, former President Calvin Coolidge dedicated a dam on the Gila River named after him. Because of a long drought, the "lake" behind it had no water! Humorist Will Rogers joked, "If that was my lake I'd mow it." Phoenix's population had almost doubled in the 1920s, reaching 48,118.

After the stock market crash of 1929, Sky Harbor Airport was sold. In 1930, American Airlines started passenger and air mail service to Phoenix. In 1935, the city of Phoenix bought the airport, and it has been owned by the city ever since. In the 1930s, couples would fly into Sky Harbor just to get married at the chapel. Arizona was one of the few states that didn't have a waiting period for marriage. Also in the 1930s, Phoenix and the surrounding area began to be called "The Valley of the Sun." This was an advertising slogan to attract more tourists.

By 1940, as the Great Depression ended, Phoenix had a population of 65,000. Its economy was still based on cotton, citrus, and cattle. It also provided shopping, banking, and government services for central Arizona. Phoenix was becoming well-known as a winter tourist spot.

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 240 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,708 | 611.7% | |

| 1890 | 3,152 | 84.5% | |

| 1900 | 5,544 | 75.9% | |

| 1910 | 11,314 | 104.1% | |

| 1920 | 29,053 | 156.8% | |

| 1930 | 48,118 | 65.6% | |

| 1940 | 65,414 | 35.9% | |

| 1950 | 106,818 | 63.3% | |

| 1960 | 439,170 | 311.1% | |

| 1970 | 581,572 | 32.4% | |

| 1980 | 789,704 | 35.8% | |

| 1990 | 983,403 | 24.5% | |

| 2000 | 1,321,045 | 34.3% | |

| 2010 | 1,445,632 | 9.4% | |

| 2012 (est.) | 1,488,750 | 3.0% | |

| sources: | |||

Phoenix in the 1940s

World War II and Phoenix

During World War II, Phoenix's economy changed. It became a center for distributing goods and started to become an industrial city, making military supplies. There were three Air Force bases nearby: Luke Field, Williams Field, and Falcon Field. There were also two large pilot training camps. These military facilities brought thousands of new people to Phoenix.

Mexican-American groups in Phoenix strongly supported the war. They encouraged men to join the military and helped their families. Many civilians worked in war-related jobs, bringing more money to the community than ever before. Some projects were done with the Anglo community, but most were separate. Many future politicians got their start during the war. The G.I. Bill of Rights after the war helped thousands of veterans buy homes.

In December 1944, 25 German prisoners of war escaped from a camp at Papago Park through a secret tunnel. It took local and federal officials a month to catch them all.

During the war, public transportation was very busy because gasoline was limited. In 1943, the city's streetcars and buses carried 20 million passengers a year. A fire in 1947 destroyed most of the streetcars, and the city switched to buses.

Post-War Growth in Phoenix

Phoenix had just over 65,000 residents in 1940. By 2010, it became America's sixth largest city, with nearly 1.5 million people. Millions more lived in the surrounding suburbs.

This rapid growth after the war was due to young veterans who had seen Phoenix and liked its potential. New industries also moved in. In 1948, high-tech industry arrived when Motorola chose Phoenix for its new research center for military electronics. Motorola liked Phoenix's business-friendly attitude, its location, and the chance for engineering programs at Arizona State College (now Arizona State University). Later, other high-tech companies like Intel and McDonnell Douglas also set up operations in the Valley.

Barry Goldwater's Impact

Barry Goldwater (1909–1998) was a very important leader in Phoenix, Arizona, and the whole country. He owned the city's largest department store. He worked to improve city government and helped build the state's Republican Party. He became a well-known senator and was called "Mr. Conservative" for his strong beliefs. He ran for president in 1964, which he lost, but his campaign helped shift the Republican Party's direction.

Goldwater was born in Phoenix before Arizona became a state. His family owned Goldwater's, a large department store. He took over the family business in 1930. Even though Arizona was mostly Democratic, Goldwater became a conservative Republican. He spoke out against some government programs he didn't like. Phoenix schools were segregated at the time. Goldwater quietly supported civil rights for Black people. He was a pilot, loved the outdoors, and was a photographer. He was very interested in Arizona's nature and history.

He entered Phoenix politics in 1949 when he was elected to the City Council. He was part of a group that promised to stop widespread gambling. This group won every mayoral and council election for 20 years. Goldwater helped strengthen the Republican party. He was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1952.

The 1950s in Phoenix

Population and Industry Boom

Phoenix grew incredibly fast in the 1950s. The population tripled, and industry grew 15 times larger! This growth brought challenges like housing for minorities, traffic, and smog. It also changed the relaxed Phoenix lifestyle. By 1950, over 105,000 people lived in the city.

A big reason for the 1950s growth was better air conditioning. This made the very hot Phoenix summers much more bearable for homes and businesses. Affordable cooling led to a huge building boom. In 1959 alone, Phoenix saw more new construction than it had in over three decades before that.

In May 1953, Phoenix became home to the very first McDonald's restaurant franchise. It was located near Central Avenue and Indian School Road. This Phoenix McDonald's was also the first to feature the famous "Golden Arches." The McDonald brothers licensed their first franchise to Phoenix businessman Neil Fox for $1,000.

Phoenix from the 1960s to 1980s

Over the next few decades, Phoenix and its surrounding area continued to grow. It became a popular tourist spot because of its unique desert setting and fun activities. Nightlife and city events were mostly along Central Avenue, which soon had many skyscrapers. In 1960, the Phoenix Corporate Center opened. It was the tallest building in Arizona at 341 feet. In 1964, the Rozenweig Center (now Phoenix City Square) was finished. The unique Phoenix Financial Center was also completed in 1964. Many other office towers and residential high-rises were built during this time.

However, Phoenix's growth wasn't even. Most of it happened on the city's north side, which was almost entirely white. In 1962, an activist said that out of 31,000 new homes in this area, not one had been sold to an African-American person. Phoenix's African-American and Mexican-American communities mostly stayed on the south side of town. Segregation was so strict that even famous baseball player Willie Mays couldn't rent a place north of Van Buren Street when he was in town for spring training in the 1960s.

In 1965, the Arizona Veterans Memorial Coliseum opened. In 1968, Phoenix surprisingly got an NBA team, the Phoenix Suns. They played their home games at the Coliseum. Also in 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson approved the Central Arizona Project. This project made sure Phoenix, Tucson, and the farming areas between them would have enough water in the future. In 1969, the Catholic church created the Diocese of Phoenix.

In 1971, Phoenix adopted the Central Phoenix Plan. This plan allowed unlimited building heights along Central Avenue. However, it didn't lead to long-term development there. Instead, the downtown area saw a comeback. Many high-rise buildings were built, including the Wells Fargo Plaza, the Chase Tower (the tallest building in Phoenix and Arizona at 483 feet), and the U.S.Bank Center. By the end of the 1970s, Phoenix adopted the Concept 2000 plan. This plan divided the city into "urban villages," each with its own center where taller and denser buildings were allowed. This helped shape Phoenix into a city with many different centers, which would later be connected by freeways. In 1972, the Phoenix Symphony Hall opened.

After the Salt River flooded in 1980, damaging many bridges, the Arizona Department of Transportation and Amtrak briefly ran a train service between central Phoenix and the southeast suburbs. It was stopped because it cost too much and local officials weren't interested in funding it. On September 25, 1981, Sandra Day O'Connor made history when she became the first female justice on the U.S. Supreme Court. In 1985, the Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station, the nation's largest nuclear power plant, started producing electricity. The Arizona Science Center opened in 1984. In 1987, Pope John Paul II and Mother Teresa visited Phoenix.

Phoenix from 1990 to Today

The new 20-story City Hall opened in 1992. The Sunnyslope area, with its low-cost housing, became popular with refugee resettlement centers. By 2000, 43 different languages were spoken in local schools there, as refugees from many countries settled in the area. Valley National, Arizona's biggest and oldest bank, was bought by Banc One Corp. in 1992. In 1993, Sheriff Joe Arpaio created "Tent City" using inmate labor to help with overcrowding in the Maricopa County Jail. The famous "Phoenix Lights" UFO sightings happened in March 1997. Also in 1997, The Phoenix Gazette newspaper closed after 116 years.

In the mid-2000s, some crime sprees happened in Phoenix and nearby cities. In July 2007, a mid-air collision between two news helicopters happened at Steele Indian School Park.

Phoenix has continued to grow rapidly in recent years. In 2008, the Phoenix Light Rail began operating, connecting Phoenix, Tempe, and Mesa. Also in 2008, Squaw Peak, the city's second tallest mountain, was officially renamed Piestewa Peak. This was in honor of Army Specialist Lori Ann Piestewa, an Arizona native who was the first Native American woman to die in combat for the U.S. military. Later that same year, Phoenix was one of the cities hit hardest by the Subprime mortgage crisis. In early 2009, the average home price was $150,000, down from a peak of $262,000. Crime rates in Phoenix have gone down, and some neighborhoods that had problems, like South Mountain and Maryvale, have improved. By 2005, Downtown Phoenix was seeing new interest and growth, with many restaurants, stores, and businesses opening or moving there.

In June 2017, a heat wave was so intense that it caused more than 40 small airline flights to be grounded. American Airlines even had to limit ticket sales on some flights to make sure planes weren't too heavy for safe takeoff in the extreme heat.