History of Saxony facts for kids

The history of Saxony began with a small tribe called the Saxons. They lived near the North Sea, between the Elbe and Eider Rivers in what is now Holstein. The Greek writer Ptolemy first wrote about them. The name Saxons comes from the Seax, a type of knife they used as a weapon.

In the 3rd and 4th centuries, many large tribes lived in Germany. These included the Alamanni, Bavarians, Thuringians, Franks, Frisii, and Saxons. Unlike other tribes, the Saxons did not have one king. Instead, they were split into many groups, each with its own leader. If there was a war, these leaders would choose one person to lead them until the fighting ended.

During the 3rd and 4th centuries, the Saxons moved west. Their territory grew to reach the old border of the Roman Empire, almost to the Rhine River. Only a small area on the right bank of the Rhine stayed with the Frankish tribe. To the south, the Saxons reached the Harz Mountains. Over time, they took over most of Thuringia. To the east, their power first reached the Elbe and Saale Rivers, and later spread even further. Most of the North Sea coast belonged to the Saxons, except for the part west of the Weser River, which the Frisians kept.

Contents

Early Saxon History

Ptolemy's Geographia, written in the 2nd century, might be the first time the Saxons were mentioned. Some copies of his book talk about a tribe called Saxones near the lower Elbe River. But other copies call them Axones. This might be a mistake for Aviones, another tribe mentioned by Tacitus in his book Germania.

However, some experts like Gudmund Schütte believe "Saxones" is correct. He noted that old writings often lost the first letter of names. He also pointed out that this area was later called "Old Saxony." This fits with what Bede wrote, saying Old Saxony was near the Rhine, north of the river Lippe. This area is now part of Westphalia in Germany.

By the 8th century, the Saxons were divided into four main groups:

- The Westphalians, living between the Rhine and the Weser.

- The Engern or Angrians, living on both sides of the Weser.

- The Eastphalians, living between the Weser and the Elbe.

- The Transalbingians, living in what is now Holstein.

Only the name Westphalians is still used today for a region in Germany.

Saxons and the Franks

The Frankish King Clovis I (who ruled from 481 to 511) brought together different Frankish tribes. He conquered Roman Gaul (modern-day France) and became a Christian. The new Frankish kingdom managed to bring almost all other Germanic tribes under its control and make them Christian. But the Saxons resisted. For over a hundred years, the Franks and Saxons fought almost constantly.

After a long and bloody war that lasted thirty years (from 772 to 804), the Saxons were finally defeated by the Emperor Charlemagne. Charlemagne's main goal was to stop the Saxons from raiding the Rhine area every year. He also strongly pushed for the Saxons to become Christian. This meant he put down their old religion. For example, in 782, he ordered the execution of 4,500 Saxons at Verden.

Medieval Duchy of Saxony (880–1356)

When the Frankish kingdom was divided by the Treaty of Verdun in 843, the land east of the Rhine became the Kingdom of the East Franks. This kingdom later grew into modern Germany. There was no strong central ruler for a while. So, each German tribe had to defend itself from attacks by Norsemen from the north and Slavs from the east. Because of this, the tribes chose their own dukes to rule them again.

The first Saxon duke was Otto the Illustrious (880–912). He was able to expand his power over Thuringia. Otto's son, Henry the Fowler, was chosen as king of Germany (919–936). Many call him the true founder of the German Empire. His son, Otto I (936–973), was the first German king not from the Carolingian family to be crowned Roman emperor by the pope in 962. His son Otto II (973–983) and grandson Otto III (983–1002) followed him.

The line of Saxon emperors ended with Henry II (1002–1024). Henry I had been both King of Germany and Duke of Saxony. He fought hard against the Slavs on his eastern border to protect his ducal lands. Emperor Otto I was also Duke of Saxony for most of his rule. He divided the lands he gained into several smaller areas called margraviates. The most important ones were the North Mark, which later became the Kingdom of Prussia, and the Margraviate of Meissen, which led to the Kingdom of Saxony. Each mark had fortified castles for military, political, and church purposes.

Otto I also set up the church in this area. He made the main fortified places into centers for dioceses (church districts). In 960, Otto I gave the ducal power over Saxony to Margrave Hermann Billung. Hermann had fought well against the Slavs. The title of duke then became hereditary in Hermann's family. This old Duchy of Saxony became a center of opposition from German princes against the emperor's power. When Duke Magnus died in 1106, the Billung ducal family ended.

Emperor Henry V (1106–25) gave the Duchy of Saxony to Count Lothair of Supplinburg. Lothair became King of Germany in 1125. When he died in 1137, he passed the Duchy of Saxony to his son-in-law, Duke Henry the Proud.

Later, Henry the Lion refused to help Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa in a war in 1176. Because of this, in 1180, Henry was banned from the empire. In 1181, the old Duchy of Saxony was broken up into many smaller parts at the Diet of Gelnhausen. A large part of its western area became the Duchy of Westphalia, given to the Archbishopric of Cologne. The Saxon bishops and many local counts and cities became "immediately subject" to the emperor. This meant they reported directly to the emperor, not to a duke.

The Diet of Gelnhausen was very important for Germany's history. Emperor Frederick made a big legal change there. But splitting up the large Saxon country into many small states was one reason why Germany later had so many small, separate states. The old duchy never again used the name Saxony. The large western part became Westphalia. However, people still used "Lower Saxony" for areas near the lower Elbe, like Hanover and Hamburg. "Upper Saxony" referred to the Kingdom of Saxony and Thuringia.

From the time the Saxons became Christian until the 16th century, religious life in the medieval Duchy of Saxony was very rich. Art, learning, poetry, and history writing grew strong in the many monasteries. Important learning centers included the cathedral and monastery schools of Corvey, Hildesheim, Paderborn, and Münster. This time also saw beautiful churches built in the Romanesque style, like the cathedrals of Goslar, Soest, and Brunswick. Many of these buildings are still standing today.

Palatinate of Saxony

King Otto I created the "Palatinate of Saxony" in the southern part of the Duchy of Saxony. This was in the Saale-Unstrut region. The first Saxon count palatine was Burchard, who ruled from 1003 to 1017. The family line of these counts palatine ended in 1179.

That same year, Emperor Frederick Barbarossa gave the Palatinate of Saxony to Louis the Pious. He then passed it to his brother Hermann in 1181. After Hermann died in 1217, the Palatinate went to his son Louis.

When Louis IV died in 1227 during a crusade, his brother Henry Raspe took over for Louis's young son, Hermann II. Hermann II died at 19 in 1241, and Henry Raspe officially became the ruler. Since Henry Raspe had no children, he arranged for his nephew, Henry the Illustrious of the House of Wettin, to inherit the Palatinate of Saxony along with the Landgraviate of Thuringia.

After Henry the Illustrious died, Duke Henry I became Count Palatine of Saxony. In 1363, a new area called Saxony-Allstedt was mentioned for the first time.

Electorate of Saxony (1356–1806)

The Protestant Reformation in the 16th century started with the support of the electors of Saxony. In 1517, Martin Luther famously posted his 95 Theses at the castle church in Wittenberg. The Electorate of Saxony remained a key place for religious conflicts during the Reformation and the later Thirty Years' War.

After the old medieval Duchy of Saxony was broken up, the name Saxony was first used for a small part of the duchy. This area was located on the Elbe River around the city of Wittenberg. In 1356, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV issued the Golden Bull. This important law set out how the emperor would be elected. The Duchy of Saxe-Wittenberg became one of the seven electorates and was renamed the Electorate of Saxony. This gave it more power than its small size might suggest. Also, being an electorate meant that the land would be passed down to the oldest child (called primogeniture). This stopped the land from being divided among many heirs, which kept the country together.

After the Thirty Years' War, Saxony's rulers and people were mostly Lutheran. However, in the 18th century, Frederick Augustus I became a Roman Catholic. He did this so he could be crowned King of Poland as Augustus II. This union between Poland and Saxony lasted until Augustus III died in 1763. During this time, most people in Saxony remained Protestant.

In 1756, Saxony joined Austria, France, and Russia against Prussia. Frederick II of Prussia attacked first, invading Saxony in August 1756. This started the Seven Years' War. The Prussians quickly defeated Saxony and forced the Saxon army to join the Prussian army. However, the Prussians made a mistake by keeping the Saxon units together instead of mixing them with their own. Many Saxon units then deserted. At the end of the Seven Years' War, Saxony became an independent state again.

In 1806, when Napoleon's French Empire went to war with Prussia, Saxony first sided with Prussia. But later, Saxony joined Napoleon and became part of the Confederation of the Rhine. The Electorate of Saxony became the Kingdom of Saxony, and Elector Frederick Augustus III became King Frederick Augustus I.

Kingdom of Saxony (1806–1918)

The new Kingdom of Saxony was an ally of France in all the Napoleonic wars from 1807 to 1813. At the start of the big German Campaign of 1813, the king of Saxony did not immediately pick a side. But when Napoleon threatened to treat Saxony as an enemy, the king joined forces with France.

At the Battle of Leipzig (October 16–18, 1813), Napoleon was completely defeated. Most of the Saxon troops switched sides and joined the allied forces. The King of Saxony was captured by the Prussians and taken to a castle near Berlin.

The Congress of Vienna (1814–15) took a large part of Saxony's land and gave it to Prussia. This included about 7,800 square miles (20,200 km2) with about 850,000 people. The ceded land included the old Duchy of Saxe-Wittenberg and parts of Lusatia. What Prussia gained, along with some older Prussian areas, became the Province of Saxony.

The Kingdom of Saxony was left with only about 5,789 square miles (14,990 km2) and 1.5 million people. With these smaller borders, it joined the German Confederation in 1815. King John (1854–73) sided with Austria in its struggle with Prussia for power in Germany. So, in the War of 1866, when Prussia won, Saxony's independence was again in danger. Only the Austrian Emperor's help saved Saxony from being completely taken over by Prussia. However, the kingdom had to join the North German Confederation, which Prussia led. In 1871, Saxony became one of the states of the newly formed German Empire.

King John was followed by his son King Albert (1873–1902). Albert was succeeded by his brother George (1902–04). George's son was King Frederick Augustus III.

The Kingdom of Saxony was the fifth largest state in the German Empire by area and third largest by population. In 1905, it was the most densely populated state in the empire and even in all of Europe. This was because many people moved there for jobs in manufacturing. In 1910, the population was over 5.3 million. Most were Evangelical Lutherans, but there were also about 218,000 Catholics and 14,000 Jews.

The Catholic population in Saxony grew mostly due to people moving there in the 19th century. Only a small part of the Catholic population could trace their faith back before the Reformation. This was in the Bautzen area. Here, some villages and two cities (Ostritz and Schirgiswalde) had mostly Catholic populations.

About 1.5% of Saxony's people were from a Slavic tribe called Wends (or "Serbjo" in their own language). These Wends, about 120,000 people, lived in Saxon and Prussian Lusatia. They were surrounded by German people, so their language and customs were slowly disappearing. About 50,000 Wends lived in the Kingdom of Saxony, and about 12,000 of them were Catholic.

Saxony After 1918

After 1918, Saxony became a state in the Weimar Republic. In October 1923, the Communist Party of Germany joined the government in Dresden. The national government, led by Chancellor Gustav Stresemann, sent troops into Saxony to remove the Communists from power.

Saxony continued to exist during the Nazi era and under Soviet occupation after World War II. However, it was dissolved in 1952. Its territory was divided into three smaller districts based in Leipzig, Dresden, and Karl-Marx-Stadt. But in 1990, when Germany reunited, Saxony was re-established with slightly changed borders.

Today, the Free State of Saxony also includes a small part of what was once Prussian Silesia. This area is around the town of Görlitz. It remained German after the war and was added to Saxony because it was too small to be a separate state. This part had only been part of Silesia after 1815. Before that, it belonged to Bohemia until 1623, and then to Saxony between 1623 and 1815.

Prussian Province of Saxony

The Prussian Province of Saxony was created in 1815. It included about 8,100 square miles (21,000 km2) of land taken from the Kingdom of Saxony. It also included some areas that already belonged to Prussia. These important areas were the Altmark, where the state of Prussia began, and the former lands of the Archbishopric of Magdeburg and the Bishopric of Halberstadt. Prussia had gained these lands in 1648 at the end of the Thirty Years' War. It also included the Eichsfeld, with the city of Erfurt and its surroundings.

Until 1802, the Eichsfeld and Erfurt had belonged to the Archbishopric of Mainz. Because of this, a large part of the population in these areas remained Catholic during the Reformation. For church matters, the Province of Saxony was assigned to the Diocese of Paderborn by a papal order in 1821.

The province had three church administrative divisions:

- The episcopal commissariat of Magdeburg, which covered the entire Magdeburg government department. It had four deaneries and 25 parishes.

- The "ecclesiastical Court" of Erfurt, which included the Merseburg government department and the eastern half of the Erfurt government department. It had two deaneries (Halle and Erfurt) and 28 parishes.

- The episcopal commissariat of Heiligenstadt, which covered the western half of the Erfurt government department, called the Upper Eichsfeld. It had 16 deaneries and 129 parishes.

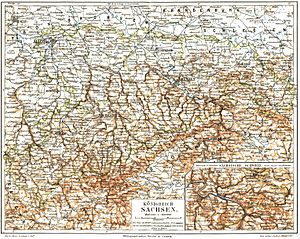

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Sajonia para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Sajonia para niños

- Electorate of Saxony

- Lower Saxony – a modern German state that is partly a successor

- Ottonian dynasty

- Rulers of Saxony

- Wettin (dynasty)

- History of cities in Saxony

- Timeline of Chemnitz

- Timeline of Dresden

- Timeline of Leipzig

| Valerie Thomas |

| Frederick McKinley Jones |

| George Edward Alcorn Jr. |

| Thomas Mensah |