History of Zürich facts for kids

Zürich has been a place where people lived for a very long time, ever since the Romans were around. A small Roman town called Turicum was started in 90 AD. It was built where a Celtic tribe, the Helvetians, already had a settlement.

Even after the Western Roman Empire ended in the 400s, Roman culture stayed strong. Later, during the time of Charlemagne's family (the Carolingians), a royal castle was built on the Lindenhof hill. Important churches, called monasteries, were also built at Grossmünster and Fraumünster.

During the Middle Ages, these churches held a lot of power in Zürich. But in the 1300s, the city's guilds (groups of skilled workers) revolted. This led Zürich to join the Swiss Confederacy, a group of independent states. Zürich then became a main center for the Swiss Reformation, led by Huldrych Zwingli. In later times, Zürich grew rich because of its silk industry.

Contents

Early History of Zürich

Ancient Settlements and Discoveries

Many old settlements from the Neolithic (New Stone Age) and Bronze Age have been found near Lake Zürich. These include places like Zürich Pressehaus and Zürich Mozartstrasse. They were discovered in the 1800s, hidden under the lake. These homes, called pile dwellings, were built on stilts. They stood on small islands and peninsulas in the swampy land between the Limmat River and Lake Zürich. This helped protect them from floods.

One important site is Zürich–Enge Alpenquai, located on the lake's shore in Enge. Nearby were other settlements at Kleiner Hafner and Grosser Hafner. These sites are part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site called "Prehistoric pile dwellings around the Alps." They are also listed as important cultural sites in Switzerland.

In 2004, archaeologists found signs of an even older Celtic settlement from before the Romans. This settlement, from the La Tène culture, was centered on the Lindenhof hill. The Celtic Helvetians lived here before the Romans arrived. The Romans then set up a customs station here for goods traveling to and from Italy.

In 1890, large lumps of fused Celtic coins were found at the Alpenquai pile dwelling site. Some of these 18,000 coins came from "Eastern Gaul," while others were "Zürich" type coins made by the local Helvetians around 100 BC. There was also a special island sanctuary for the Helvetians near the Grosser Hafner island.

In 2017, during a building project in Aussersihl, archaeologists found the burial of a woman who died around 200 BC. She was buried in a carved tree trunk. Experts believe she was about 40 years old and didn't do much hard physical work. They also found her sheepskin coat, a belt chain, a fancy wool dress, a scarf, and a necklace made of glass and amber beads.

Zürich in Roman Times

The Roman town, or Vicus Turicum, was first part of the province of Gallia Belgica. From 90 AD, it belonged to Germania superior. After a big change by Emperor Constantine in 318 AD, the border between two large Roman regions was just east of Turicum.

Roman Turicum was not a strong fortress, but it had a small group of soldiers. They were stationed at a tax-collecting point where goods entering Gaul were loaded onto bigger ships. South of the Roman fort, where St. Peter's church now stands, there was a temple dedicated to the Roman god Jupiter. The oldest mention of the town's name is on a tombstone from the 2nd century. It calls the Roman fort "STA(tio) TUR(i)CEN(sis)," meaning "Turicum Station."

The area became Christian in the 300s, like the rest of the Roman Empire. A legend says that two saints, Felix and Regula, were executed at the Wasserkirche in 286 AD.

The Alamanni people settled in the Swiss plateau starting in the 400s. However, the Roman fort in Zürich lasted until the 600s. The earliest written mention of the settlement, as castellum turegum, describes a visit by Columban in 610 AD. An 8th-century list of place names from Ravenna mentions Ziurichi. There's also a legend about an Alamannic duke named Uotila who lived on the Uetliberg mountain, which is named after him.

Zürich in the Holy Roman Empire

From 746 AD, Zürich was part of Frankish-ruled Alemannia, after an event called the blood court at Cannstatt. It was located in the Turgowe (which became Thurgau), an area controlled by Konstanz.

A castle from the Carolingian period was built on the old Roman fort site by Louis the German, Charlemagne's grandson. It was first mentioned in 835 AD. Louis also founded the Fraumünster church on July 21, 853, for his daughter Hildegard. He gave this church, which was a Benedictine convent, lands in Zürich, Uri, and the Albis forest. He also made the convent independent, placing it directly under his authority.

Because of this, Zürich slowly grew into a medieval city during the 800s. It became the center of its own region, called Zürichgau, separate from the older Thurgau. The Fraumünster convent was very powerful in the early city. In 1045, King Henry III gave the convent the right to hold markets, collect taxes, and make coins. This made the abbess (the head of the convent) the effective ruler of the city.

The Frankish kings had special rights over their tenants and protected the two main churches. In 870, the king gave all his powers to one official, called the Reichsvogt. The city became even stronger when a wall was built around its four settlements in the 900s to protect against invaders.

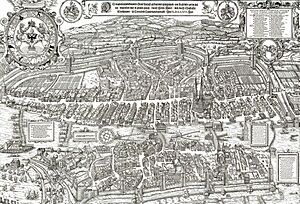

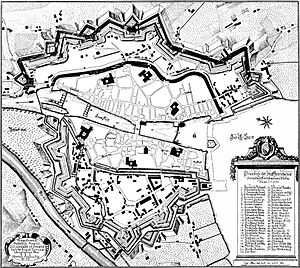

Zürich became directly controlled by the emperor (reichsunmittelbar) in 1218. A city wall was built in the 1230s, covering an area of about 38 hectares (94 acres). The street Bahnhofstrasse now follows where the western moat used to be. The oldest stone houses of citizens from this time are at Rennweg. They used stones from the old Carolingian castle, which was falling apart.

In 1234, Emperor Frederick II made the abbess of the Fraumünster a duchess. The abbess chose the mayor and often let citizens make coins.

The power of the Reichsvogtei passed to different noble families over time. Meanwhile, the abbess of the Fraumünster gained many rights and special powers over the people. The town grew a lot in the 1100s and 1200s, especially with the silk trade from Italy.

In 1218, the Reichsvogtei went back to the king. He appointed a citizen as his deputy, making Zürich a free imperial city under the distant emperor. The abbess became a princess of the empire in 1234. However, power quickly shifted from her to a council. This council, which the abbess had first chosen to handle police matters, later became elected by the citizens. The abbess was still the "lady of Zürich."

This powerful council (in charge since 1304) was made up of rich noble and merchant families, called patricians. They kept craftsmen out of the government, even though these craftsmen were largely responsible for the city's growing wealth.

The Predigerkirche church was built in 1231 AD. It was a Romanesque church belonging to the Dominican Predigerkloster monastery. Like other monasteries in Zürich, it was closed after the Reformation in Switzerland.

In October 1291, Zürich formed an alliance with Uri and Schwyz. In 1292, Zürich tried to take the Habsburg town of Winterthur but failed. After this, Zürich started to lean more towards Austria. In 1315, men from Zürich fought against the Swiss Confederates at the Battle of Morgarten.

The Codex Manesse, a very important collection of medieval German poems, was created in Zürich in the early 1300s. It includes poems by Süsskind von Trimberg. Not much is known about Süsskind, but some scholars think he was Jewish because of his name. The first official mention of Jewish people in Zürich was in 1273. A synagogue in the 1200s shows that there was an active Jewish community. When the Black Death arrived in Switzerland in 1348-1349, Jewish people were often wrongly accused of poisoning wells. On February 24, 1349, the Jewish people of Zürich were tortured, burned, and forced out of the city.

From 1354, Jewish people began to return to Zürich. But after 1400, their legal situation got worse. A law in 1404 stopped them from testifying against Christians in court. In 1423, they were permanently expelled from the city.

In the later Middle Ages, the power of the convent slowly decreased. Self-government began with the creation of the Zunftordnung (guild laws) in 1336 by Rudolf Brun. He became the first independent mayor, meaning he was not chosen by the abbess. From this time, the city was increasingly controlled by the Zünfte (guilds). This process was fully completed in the 1500s when the monasteries were closed after the Reformation. Jewish people were not allowed to join the guilds, as they were based on the idea of Christian brotherhood.

Under the new government (which lasted until 1798), the Little Council had the mayor and thirteen members from the Constafel (rich citizens) and thirteen masters from the craft guilds. Each of these 26 members held office for six months. The Great Council had 200 members (actually 212). It included the Little Council, plus 78 representatives from the Constafel and 78 from the guilds, and 3 members chosen by the mayor. The position of mayor was created and given to Brun for life. This change led to a conflict with a branch of the Habsburg family. Because of this, Brun decided to join Zürich with the Swiss Confederation in May 1351.

Zürich's dual role as a free imperial city and a member of the Everlasting League soon caused problems. In 1373 and 1393, the Constafel's powers were limited, and the craftsmen gained more control in the government. They could then even become mayor. Meanwhile, the town had been expanding its control far beyond its walls. This process began in the 1300s and reached its peak in the 1400s (1362–1467).

Joining the Swiss Confederacy

Zürich joined the Swiss Confederation as the fifth member in 1351. At that time, the Confederation was a loose group of independent states. Zürich was kicked out of the Confederation in 1440 because of a war with other member states over the Toggenburg area. This was called the Old Zürich War. Zürich was defeated in 1446 and allowed back into the Confederation in 1450.

In the second half of the 1400s, Zürich greatly increased the land it controlled. It gained Thurgau (1460), Winterthur (1467), Stein am Rhein (1459/84), and Eglisau (1496). Zürich's position in the Confederation became even stronger because of its role in the Burgundy Wars under Hans Waldmann. From 1468 to 1519, Zürich was the leading city (Vorort) of the Federal Diet.

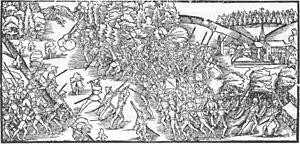

This desire for more land led to the first civil war in the Confederation, the "Old Zürich War" (1436-1450). At the Battle of St. Jakob an der Sihl in 1443, near Zürich's walls, the men of Zürich were completely defeated, and their mayor, Stissi, was killed. Buying the town of Winterthur from the Habsburgs in 1467 marked the highest point of the city's land power.

The men of Zürich and their leader Hans Waldmann helped win the Battle of Morat in 1476 during the Burgundian Wars. Zürich also played a big part in the Italian campaigns from 1512 to 1515. Its trade connections with Italy likely led it to focus on southern policies.

In 1400, the town received special rights from King Wenceslaus. These rights gave it complete independence from the empire and the power to handle criminal cases. By 1393, the Great Council had already gained most of the power, and this change was officially recognized in 1498.

This shift of power to the guilds was one of the goals of Mayor Hans Waldmann (1483–1489). He wanted to make Zürich a major trading center. He also brought in many financial and moral changes. He made the interests of the city more important than those of the countryside. He practically ruled the Swiss Confederation, and under him, Zürich became the real capital of the League. But such big changes caused opposition, and he was overthrown and executed. However, his main ideas were included in the government rules of 1498. These rules made the patricians the first of the guilds and stayed in place until 1798. Some special rights were also given to people in the country areas. Zürich's important role in adopting and spreading the ideas of the Protestant Reformation (despite strong opposition) finally made it the leader in the Confederation. The Augustiner and Prediger monasteries, and the Oetenbach nunnery and Rüti Monastery were also closed in 1524. After the Reformation in Zürich, church services stopped, and the buildings and money of the monasteries were used by the city government.

The Reformation in Zürich

Zwingli started the Swiss Reformation when he was the main preacher at the Grossmünster church in Zürich. He began by preaching through the entire book of Matthew, which was very different from other priests who followed the Church's set readings.

He lived and preached in Zürich from 1484 until he died in 1531. He was killed when Zürich was defeated in the second war of Kappel. Zwingli's Zürich Bible first came out in 1531 and has been updated many times since. Katharina von Zimmern (1478-1547), the last abbess of the Fraumünster Abbey, helped bring the Reformation to Zürich peacefully.

Early Modern History

An important collection of interesting documents from 1560 to 1587, called the Wickiana, tells us a lot about Zürich during the time of Heinrich Bullinger. During the 1500s and 1600s, Zürich's rich families and council became more aristocratic and isolated. A clear sign of this was the building of a second ring of impressive city walls in 1642. This was done because of the Thirty Years' War.

The money needed for this big project was taken from the areas under Zürich's control without asking them. This led to revolts that were put down by force. From 1648, the city officially changed its status from a "Free Imperial City" (Reichsstadt) to a "Republic." This made it similar to city-republics like Venice and Genoa.

In the 1600s and 1700s, the city government tended to keep power within a small group. For example, the country districts were only consulted for the last time in 1620 and 1640. This broke earlier agreements from 1489 and 1531, which said the districts' consent was needed for important alliances, war, and peace. This caused problems in 1777.

The council of 200 members was mostly chosen by a small group of guild members already on the council. By 1713, the council had 50 members from the Little Council, 18 from the Constafel, and 144 chosen by the 12 guilds. These 162 members were chosen for life by other council members from their own guild.

In the early 1700s, a strong effort was made to stop the growing silk trade in Winterthur by adding high taxes. Around 1650, it was estimated that about 9,000 privileged citizens ruled over 170,000 people. The first signs of unhappiness appeared later among people living by the lake. In 1794, they formed a club in Stäfa and demanded that their freedoms from 1489 and 1531 be restored. This movement was stopped by force in 1795. The old government system in Zürich, like elsewhere in Switzerland, ended with the French invasion in the spring of 1798. Under the Helvetic government, the country districts gained political freedom.

Modern History of Zürich

The Napoleonic Era

Zürich lost much of its power during the Helvetic Republic. Some of its land was given to Aargau, Thurgau, and the Canton of Linth. In 1799, the city became a battlefield during the French Revolutionary Wars. The First Battle of Zürich happened in June, and the Second Battle of Zürich in September. Gottfried Keller was an important thinker who influenced the creation of Switzerland as a federal state.

The area around Zürich is famous in military history because of the two battles in 1799. In the first battle (June 4), the French army, led by General André Masséna, was attacked by the Austrians. Masséna pulled his troops back behind the Limmat river. The second, more important battle took place on September 25 and 26. Masséna's forces crossed the Limmat and completely defeated the Russian and Austrian armies.

The 1800s in Zürich

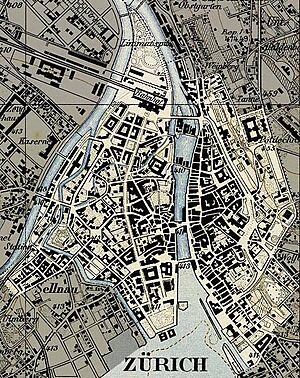

In 1839, the city had to give in to the demands of its rural citizens after an event called the Züriputsch on September 6. Most of the city walls built in the 1600s were torn down. They had never been attacked, but removing them helped calm fears that the city was too powerful. The Limmatquai was built in stages between 1823 and 1859 along the Limmat River. In 1847, the Spanisch-Brötli-Bahn, Switzerland's first railway, connected Zürich with Baden. This made the Zürich Hauptbahnhof (main train station) the start of Switzerland's rail network. The current Hauptbahnhof building dates from 1871. The Sechseläuten festival, a major traditional holiday for the city's guilds, became very popular during this time.

The Ötenbach monastery, founded in 1285, was removed in 1902 due to large city planning projects. The entire Lindenhof hill it was built on was changed to make way for new streets and buildings. The monastery had been used as a prison, and the prisoners were moved to a new cantonal prison. However, under the cantonal government rules of 1814, things were even worse. The city (with 10,000 people) had 130 representatives in the Great Council, while the countryside (with 200,000 people) had only 82. A big meeting in Uster on November 22, 1830, demanded that two-thirds of the Great Council members should be chosen by the country districts. In 1831, new rules were made following these ideas. The city got 71 representatives, compared to 141 for the country districts. It wasn't until 1837-1838 that the city finally lost its last special privileges compared to the country areas.

From 1803 to 1814, Zürich was one of six leading regions. Its chief official became the chief official of the Confederation for a year. In 1815, it was one of three regions whose government acted as the Federal government when the main assembly was not meeting. In 1833, Zürich tried hard to change the Federal government rules and create a strong central government.

The town was the Federal capital in 1839–1840. So, when the Conservative party won power there in 1839, it caused a big stir across Switzerland. This win was due to anger at the Radical government appointing David Strauss, author of a famous book about Jesus, to a university theology position. But when the Radicals regained power in Zürich in 1845, and Zürich was again the Federal capital in 1845–1846, the town led the opposition against the Sonderbund regions.

Zürich voted for the Federal government rules in 1848 and 1874. The cantonal government rules of 1869 were very modern for their time. Many people moved from the countryside to the city from the 1830s onwards. This created an industrial working class. Even though they lived in the city, they didn't have the full rights of citizens and couldn't participate in city government.

First, in 1860, city schools, which had charged high fees for non-citizens, were made open to everyone. Then, in 1875, living in the city for ten years automatically gave people citizenship rights.

In 1862, Jewish people were given full legal and political equality. That same year, the Israelitische Cultusgemeinde Zürich (Jewish Community of Zürich) was founded. Jewish people had started to resettle in Zürich during the 1800s, after 400 years of being excluded.

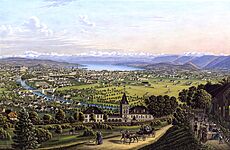

The Quaianlagen (lakefront promenades) and Quaibrücke (bridge) were important steps in Zürich becoming a modern city. By building the new lakefront, Zürich changed from a medieval town on the Limmat and Sihl rivers to an attractive modern city on Lake Zürich. This was guided by city engineer Arnold Bürkli.

The town and canton continued to be on the Liberal, Radical, or even Socialistic side. From 1848 to 1907, they had 7 of the 37 members of the Federal government (Bundesrat). These 7 members served as the president of the Confederation twelve times, a record no other canton surpassed. From 1833 onwards, Zürich's walls and fortifications were slowly torn down. This allowed the town to expand and become more beautiful. In 1915, the tenant organization Mieterverband was founded in Zürich.

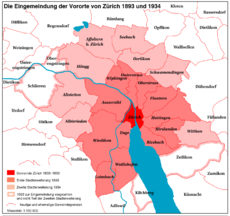

City Expansions

In 1893, the city grew bigger (called grosse Eingemeindung) to include former villages. These included Wollishofen, Enge, Leimbach, Wiedikon, Wipkingen, Fluntern, and Hottingen. It also included areas that had recently been built up, like Aussersihl, Oberstrass, Unterstrass, Riesbach, and Hirslanden.

In 1934, the city borders were expanded again (kleine Eingemeindung). This included former villages that had become suburbs, such as Albisrieden, Altstetten, Höngg, Affoltern, Seebach, Oerlikon, Schwamendingen, and Witikon.

There were no changes between 1934 and 2013. But as of December 2014, two more mergers of municipalities happened in the canton of Zürich. On January 1, 2014, Bertschikon bei Attikon and Wiesendangen merged to form Wiesendangen. On January 1, 2015, Bauma and Sternenberg merged to form Bauma. So, the Canton of Zürich now has 169 municipalities.

From the 1940s to Today

Zürich was accidentally bombed during World War II. Many Jewish people sought safety in Switzerland. Money was raised to help them, not by Swiss authorities, but by the SIG (Israelite Community of Switzerland). The main committee for refugee aid, started in 1933, was located in Zürich.

After World War II, the economy grew very quickly, lasting into the 1960s.

In 1980, there were youth protests in Zürich called Opernhauskrawalle (Opera House Riots), also known as Züri brännt (Zürich is burning). These happened because of very high government funding for the opera house, but not enough cultural programs for young people. The protests were documented in a Swiss film called Züri brännt (movie). A key politician involved was Emilie Lieberherr. In 1982, city elections resulted in the first conservative majority in 53 years. However, in the early 1980s, Emilie Lieberherr and Ursula Koch became the first female politicians in Zürich's city government, both from the Social Democratic Party.

From 1990, a leftist majority has been in power. The introduction of more relaxed laws in 1997 helped Zürich become a major center for nightlife. Also, in the 1990s, changes to zoning laws led to new construction projects. More people started moving to the suburbs from the 1960s, causing traffic jams for commuters. This was partly helped by the Zürich S-Bahn (commuter train system), which started in 1990. The population decreased during the 1980s and 1990s but began to grow again in the 2000s. This also led to gentrification (when an area becomes more expensive and changes character) in central areas.

Population Changes in Zürich

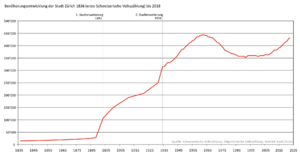

During its time of growth and wealth in the late 1300s to early 1400s, Zürich's population grew to an estimated 7,000 people. This number quickly dropped to about 5,000 after the Old Zürich War, similar to cities like Berne or Lucerne.

The population grew slowly but steadily from the 1500s to the 1700s, reaching 10,000 by 1800. Then, the population increased rapidly in the 1800s because of industrialization and more building space after the city walls were destroyed. It reached 28,000 by 1888.

If we count the population within today's city borders, the numbers are: 17,200 in 1800, 56,700 in 1871, 150,700 in 1900, and 251,000 in 1930. The population grew quickly from 1945 to 1965, reaching a peak of 440,000. After 1965, the population decreased due to people moving to the suburbs, falling below 360,000 in the 1990s. After 2000, the population started growing again, passing 400,000 in 2014.

|

See also

- History of the Jewish Community in Zürich

- Fortifications of Zürich

- Reformation in Zürich

- Staatsarchiv Zürich

- Timeline of Zürich

- History of Switzerland