History of Switzerland facts for kids

Switzerland has been a special kind of country since 1848. It's a federal republic, which means it's made up of many smaller states called cantons. These cantons have a lot of freedom to govern themselves. Some of them have been working together for over 700 years, making Switzerland one of the oldest republics in the world!

The early story of Switzerland is connected to the Alps mountains. Long ago, a group called the Helvetii lived here. In the 1st century BC, the Roman Empire took control. Later, during a time called the Migration period, Germanic tribes mixed with the Roman culture. The eastern part of Switzerland became Alemanni territory.

In the 6th century, the area became part of the Frankish Empire. Later, in the High Middle Ages, the eastern part joined the Holy Roman Empire, while the western part was part of Burgundy.

The Old Swiss Confederacy started in the Late Middle Ages. This group of eight cantons became independent from the powerful House of Habsburg and the Duchy of Burgundy. They even won land south of the Alps during the Italian Wars. But then, the Swiss Reformation (a big religious change) divided the country. This led to many internal fights between the now thirteen cantons.

After the French Revolution, France invaded Switzerland in 1798. Switzerland became a French-controlled state called the Helvetic Republic. But in 1803, Napoleon Bonaparte helped Switzerland become a confederation again. After Napoleon's time, Switzerland faced some problems, including a short civil war in 1847. This led to a new federal constitution in 1848, which is still the basis of Switzerland today.

Since 1848, Switzerland has mostly seen success and growth. Industrialisation changed the country from farming to factories. Switzerland stayed neutral during the World Wars. The success of its banking industry also helped it become one of the world's most stable economies.

Switzerland signed a trade agreement with the European Economic Community in 1972. It has worked closely with the European Union (EU) through special agreements. However, it has chosen not to join the EU, even though it's almost completely surrounded by EU countries. In 2002, Switzerland finally joined the United Nations.

Contents

Early History of Switzerland

Prehistoric Times

Scientists have found signs that hunter-gatherers lived in the lowlands north of the Alps as far back as 150,000 years ago. Farming started around 5500 BC. By the Neolithic period, many people lived in the area. We've found remains of pile dwellings (houses built on stilts over water) from 3800 BC in many lakes. Around 1500 BC, Celtic tribes settled here. The Raetians lived in the east, and the Helvetii lived in the west.

In 2017, archaeologists found a woman buried in a carved tree trunk in Aussersihl. She died around 200 BC and was about 40 years old. She probably didn't do much hard physical work. They also found her sheepskin coat, a belt chain, a fancy wool dress, a scarf, and a pendant made of glass and amber beads.

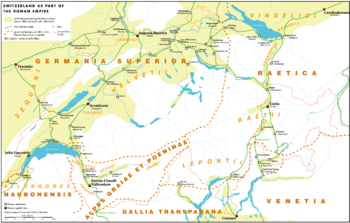

Roman Times

In 58 BC, the Helvetii tried to move into Gaul to escape pressure from Germanic tribes. But Julius Caesar's armies defeated them and sent them back. The Roman Empire then took over the Alps region. Over the next centuries, the area became very Roman. The main Roman city was Aventicum (Avenches). In 259 AD, Alamanni tribes crossed the Roman border, making Swiss settlements a frontier area.

The first Christian church leaders were established in the fourth century.

When the Western Roman Empire fell, Germanic tribes moved into the area. Burgundians settled in the west. In the north, Alamanni settlers slowly pushed the Celto-Roman people into the mountains. Burgundy became part of the Frankish kingdom in 534, and the Alamans followed two years later. In the Alaman-controlled area, Christianity almost disappeared, but Irish monks brought it back in the early 7th century.

The Middle Ages

Under the Carolingian kings, the feudal system grew. Monasteries and bishoprics were important for keeping control. In 843, the Treaty of Verdun divided the land. Western Switzerland (Upper Burgundy) went to Lotharingia, and eastern Switzerland (Alemannia) went to the eastern kingdom, which became part of the Holy Roman Empire.

In the 10th century, the Carolingian rule weakened. Magyars destroyed Basel in 917 and St. Gallen in 926. After King Otto I defeated the Magyars in 955, the Swiss lands were brought back into the empire.

In the 12th century, the dukes of Zähringen gained power over parts of Burgundy, including western Switzerland. They founded many cities, like Fribourg in 1157 and Bern in 1191. When the Zähringer family ended in 1218, their cities became reichsfrei (like independent city-states within the Holy Roman Empire). Other families, like the Kyburg and Habsburg, fought for control of the rural areas.

Under the Hohenstaufen rulers, the mountain passes in Raetia and the St Gotthard Pass became very important. The St. Gotthard Pass was a key direct route through the mountains. Uri (in 1231) and Schwyz (in 1240) were given Reichsfreiheit to give the empire direct control over the pass. Most of Unterwalden at this time belonged to monasteries that were also independent.

When the Kyburg family died out, the Habsburg family gained control of much of the land south of the Rhine. This helped them become very powerful. Rudolph of Habsburg, who became King of Germany in 1273, took away the independent status of Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden. These "Forest Cantons" then lost their freedom and were ruled by local governors called reeves.

The Old Confederacy (1300–1798)

Forming the Old Swiss Confederacy

On August 1, 1291, the cantons of Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden joined together to protect peace after the death of Emperor Rudolf I of Habsburg. This was the start of the Old Swiss Confederacy.

By 1353, the original three cantons were joined by Glarus, Zug, and the city-states of Lucerne, Zürich, and Bern. This formed the "Old Federation" of eight states. The Holy Roman Empire built roads and bridges to connect northern Italy with the Rhine river. This made the local farmers and bankers rich, allowing them to buy special Italian armor and stop paying road taxes to the Empire. At the Battle of Sempach in 1386, the Swiss defeated the Habsburgs, gaining more independence within the Holy Roman Empire.

Zürich was kicked out of the Confederation from 1440 to 1450 because of a fight over the Toggenburg area (the Old Zürich War). The Confederation's power and wealth grew a lot after victories over Charles the Bold of Burgundy during the Burgundian Wars (1474–1477). This was largely thanks to the Swiss mercenaries, who were professional soldiers from the Swiss cantons. They were famous for fighting in foreign armies, especially for the Kings of France, from the Late Middle Ages to the Renaissance. Their skills made them highly sought-after troops. The traditional order of the Swiss cantons today still shows this history, listing the eight "Old Cantons" first, then the cantons that joined later.

The Swiss defeated the Swabian League in 1499. This gave them even more freedom within the Holy Roman Empire, including being free from many imperial laws and courts. In 1506, Pope Julius II hired the Swiss Guard, who still protect the Pope today. The Confederation's growth and reputation for being unbeatable faced a challenge in 1515 with defeats in the Battle of Marignano and Battle of Bicocca.

The Reformation

The Reformation in Switzerland started in 1523, led by Huldrych Zwingli, a priest in Zürich. Zürich became Protestant, along with Berne, Basel, and Schaffhausen. But Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Nidwalden, Zug, Fribourg, and Solothurn stayed Catholic. Glarus and Appenzell were split. This led to several religious wars between the cantons in 1529 and 1531. Each canton often made the opposing religion illegal. Even though there were two separate meetings (one Protestant, one Catholic), the Confederation managed to survive.

Early Modern Switzerland

During the Thirty Years' War (a big war in Europe), Switzerland was a peaceful and wealthy place. This was mainly because all the major European powers relied on Swiss mercenaries. They didn't want Switzerland to fall into the hands of their enemies. At the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648, Switzerland officially became legally independent from the Holy Roman Empire.

In 1653, farmers in areas controlled by Lucerne, Bern, Solothurn, and Basel rebelled because money was losing its value. The authorities won, but they did make some tax changes. This event prevented Switzerland from becoming an absolute monarchy, unlike some other European countries. However, religious tensions remained. They led to more conflicts in 1656 and 1712.

Napoleon's Time and After (1798–1848)

French Invasion and Helvetic Republic

During the French Revolutionary Wars, the French army invaded Switzerland. They turned it into an ally called the "Helvetic Republic" (1798–1803). This new government was very central, with little power for the cantons. Many Swiss people didn't like this interference with their local traditions and freedoms, even though some modern changes happened.

Resistance was strongest in the traditional Catholic areas, with armed uprisings in 1798. The French army stopped these uprisings, but support for revolutionary ideas quickly faded. Most Swiss people disliked losing their local democracy, the new central government, new taxes, wars, and hostility towards religion.

In 1803, Napoleon's "Act of Mediation" gave some power back to the cantons. New cantons like Aargau, Thurgau, Grisons, St. Gallen, Vaud, and Ticino became equal members. Napoleon and his enemies fought many battles in Switzerland, which damaged many towns.

Restoring Independence

The Congress of Vienna in 1814–15 fully brought back Switzerland's independence. European powers agreed to always respect Switzerland's neutrality. At this time, Valais, Neuchâtel, and Geneva also joined Switzerland as new cantons, making Switzerland's borders what they are today.

The French Revolution had a lasting impact. It brought ideas like equality for all citizens, equal languages, and freedom of thought and religion. It created Swiss citizenship, which is the basis of modern Switzerland. It also brought the idea of separating government powers, which the old system didn't have. It removed internal trade taxes, unified weights and measures, reformed laws, allowed mixed marriages (Catholic and Protestant), stopped torture, and improved justice. It also helped develop education and public works.

On April 6, 1814, delegates from all nineteen cantons met in Zurich to create a new constitution.

From 1814, each canton created its own constitution, generally bringing back the old feudal ways of the 17th and 18th centuries. The national assembly (Tagsatzung) was reorganized by the Federal Treaty of August 7, 1815.

The liberal Free Democratic Party of Switzerland was strong in the Protestant cantons. They gained a majority in the national assembly in the early 1840s. They proposed a new constitution to bring the cantons closer together. This new constitution also included protections for trade and other modern reforms. The national assembly, with approval from most cantons, took actions against the Catholic Church, like closing monasteries in Aargau in 1841. In response, Catholic Lucerne brought back the Jesuits to lead its education in 1844. This led seven Catholic cantons to form a separate alliance called the "Sonderbund." This caused the Protestant cantons to take control of the national assembly in 1847. The assembly ordered the Sonderbund to break up, leading to a short civil war.

The Sonderbund War of 1847

The Protestant group said the Sonderbund broke the Federal Treaty of 1815, which clearly forbade such separate alliances. Since they had a majority in the national assembly, they decided to dissolve the Sonderbund on October 21, 1847. The Catholic cantons were at a disadvantage; they had fewer people and fewer well-trained soldiers and leaders. When the Sonderbund refused to disband, the national army attacked. This led to a short civil war between the Catholic and Protestant cantons, known as the Sonderbundskrieg. The national army was made of soldiers from all other cantons except Neuchâtel and Appenzell Innerrhoden (who stayed neutral). The Sonderbund was easily defeated in less than a month, with about 130 people killed. This was the last armed conflict on Swiss land. Many Sonderbund leaders fled to Italy, but the winners were fair. They invited the defeated cantons to join them in creating a new federal system, and a new constitution was written, similar to the American one. National issues would be controlled by the national parliament, and the Jesuits were expelled. The Swiss people voted strongly for the new constitution. Switzerland became peaceful. However, conservative leaders across Europe became worried and prepared their armies, which soon led to the Revolutions of 1848 in other countries.

Modern Switzerland (1848–Present)

Industrial Growth

After the civil war, Switzerland adopted a federal constitution in 1848. It was updated in 1874. This constitution gave the federal government responsibility for defense, trade, and legal matters, leaving other issues to the cantonal governments. From then on, and throughout much of the 20th century, Switzerland saw continuous political, economic, and social improvements.

While Switzerland was mostly rural, its cities experienced an industrial revolution in the late 19th century, especially in textiles. In Basel, for example, textiles, including silk, were the main industry. In 1888, women made up 44% of the workers. Nearly half of the women worked in textile mills, with household servants being the next largest job. The number of women in the workforce was actually higher between 1890 and 1910 than in the late 1960s and 1970s.

Swiss universities in the late 19th century were notable for the number of female students studying medicine.

World Wars (1914–1945)

The major world powers respected Switzerland's neutrality during World War I.

While industry started growing in the mid-19th century, Switzerland's rise as one of Europe's richest nations – often called the "Swiss miracle" – happened mostly in the 20th century. This was partly due to Switzerland's role during the World Wars.

Germany thought about invading Switzerland during World War II but never did. Under General Henri Guisan, the Swiss army prepared for a large mobilization of citizen soldiers against invasion. They built strong, well-stocked positions high in the Alps called the Réduit. Switzerland stayed independent and neutral because of its strong military defense, economic deals with Germany, and good luck as bigger events in the war kept an invasion from happening.

Attempts by Switzerland's small Nazi party to join Germany failed badly. This was because of Switzerland's many cultures, strong national identity, and long history of direct democracy and freedoms. The Swiss press strongly criticized Nazi Germany, often making German leaders angry. Switzerland was an important base for spies from both sides during the war. It also often helped communicate between the Axis and Allied powers.

Switzerland's trade was blocked by both the Allies and the Axis. Both sides pressured Switzerland not to trade with the other. Switzerland's economic cooperation with Germany changed depending on how likely an invasion seemed and if other trading partners were available. These deals were at their highest after a key railway link through France was cut in 1942, leaving Switzerland surrounded by Axis countries. Switzerland relied on trade for half its food and almost all its fuel. However, it controlled vital railway tunnels through the Alps between Germany and Italy.

Switzerland's most important exports during the war were precision machine tools, watches, special bearings (used in bombsights), electricity, and dairy products. During World War II, the Swiss franc was the only major currency that could be freely exchanged in the world. Both the Allies and the Germans sold large amounts of gold to the Swiss National Bank. Between 1940 and 1945, the German central bank sold 1.3 billion francs worth of gold to Swiss banks.

Hundreds of millions of francs worth of this gold was stolen from the central banks of occupied countries. About 581,000 francs of gold taken from Holocaust victims was also sold to Swiss banks. Overall, trade between Germany and Switzerland contributed about 0.5% to Germany's war effort, but it didn't significantly make the war last longer.

During the war, Switzerland took in 300,000 refugees. About 104,000 of these were foreign soldiers who were kept in Switzerland according to international rules for neutral countries. The rest were foreign civilians who were either kept in camps or given permission to live in Switzerland by local authorities. Refugees were not allowed to work. Between 26,000 and 27,000 of the civilian refugees were Jewish people escaping Nazi persecution. However, between 10,000 and 25,000 civilian refugees were not allowed into Switzerland. At the start of the war, Switzerland had a Jewish population of 18,000 to 28,000, out of a total population of about 4 million.

Within Switzerland during the conflict, there were different opinions. Some people were against all wars. Some supported international capitalism or communism. Others leaned towards their language group, with some in French-speaking areas being more pro-Allied, and some in German-speaking areas being more pro-Axis. The government tried to stop anyone or any group in Switzerland that acted extremely or tried to break the country's unity. The Swiss-German speaking areas started to speak less like standard German, focusing more on local Swiss dialects.

In the 1960s, there was a lot of debate among historians about Switzerland's relationship with Nazi Germany.

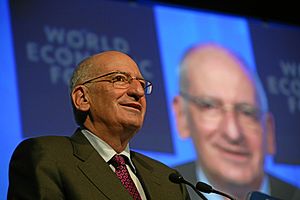

By the 1990s, these debates included a lawsuit in New York about Jewish assets in bank accounts from the Holocaust era. The government ordered an official study of Switzerland's interactions with the Nazi regime. The final report from this group of international scholars, known as the Bergier Commission, was released in 2002.

Switzerland After 1945

During the Cold War, Swiss authorities thought about building a Swiss nuclear bomb. Leading scientists at the Federal Institute of Technology Zurich made this seem possible. However, money problems in the defense budget prevented large funds from being spent. The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty of 1968 was also seen as a good alternative. All plans for building nuclear weapons were dropped by 1988.

Since 1959, the Federal Council, which is elected by the parliament, has included members from the four main political parties: the Protestant Free Democrats, the Catholic Christian Democrats, the left-wing Social Democrats, and the right-wing People's Party. This system means there isn't a large group opposing the government, reflecting the strong position of opposition in a direct democracy.

In 1963, Switzerland joined the Council of Europe. In 1979, parts of the canton of Bern became independent, forming the new canton of Jura.

Switzerland's involvement in many United Nations and international organizations helped balance its concern for neutrality. In 2002, Swiss voters approved joining the United Nations with 55% of the vote. This followed decades of debate and a previous rejection of membership in 1986.

Swiss women gained the right to vote in national elections in 1971. An equal rights amendment was approved in 1981. However, it wasn't until 1990 that courts fully established voting rights for women in all elections across the country.

Switzerland is not a member of the EU, but it has been surrounded by EU territory since Austria joined in 1995. In 2005, Switzerland voted to join the Schengen treaty and Dublin Convention. In February 2014, Swiss voters approved a vote to bring back limits on immigration to Switzerland. This started a period of trying to find a way to do this without breaking the EU's free movement agreements that Switzerland had adopted.

After the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Switzerland decided to adopt all EU sanctions against Russia. According to the Swiss President Ignazio Cassis, these actions were "unprecedented but consistent with Swiss neutrality". The government also confirmed that Switzerland would continue to offer its help to find a peaceful solution to the conflict. Switzerland only takes part in humanitarian missions and provides aid to the Ukrainian people and neighboring countries.

Order of Cantons Joining Switzerland

The order of the Swiss cantons listed in the federal constitution follows the historical order they joined. However, the three city cantons of Zürich, Bern, and Lucerne are listed first.

- Eight Cantons

- 1291 founding cantons –

Uri,

Uri,  Schwyz,

Schwyz,  Unterwalden

Unterwalden - 1332 –

Lucerne

Lucerne - 1351 –

Zürich

Zürich - 1352 –

Glarus,

Glarus,  Zug

Zug - 1353 –

Bern

Bern

- expansion to Thirteen Cantons

- 1481 –

Fribourg,

Fribourg,  Solothurn

Solothurn - 1501 –

Basel,

Basel,  Schaffhausen

Schaffhausen - 1513 –

Appenzell

Appenzell

- Act of Mediation

- 1803 –

St. Gallen,

St. Gallen,  Graubünden,

Graubünden,  Aargau,

Aargau,  Thurgau,

Thurgau,  Ticino,

Ticino,  Vaud

Vaud

- Restoration period

- Switzerland as a federal state

- 1979 –

Jura (secession from Bern)

Jura (secession from Bern) - 1999 – official status of the six half-cantons as cantons (

Obwalden and

Obwalden and  Nidwalden,

Nidwalden,  Appenzell Ausserrhoden and

Appenzell Ausserrhoden and  Appenzell Innerrhoden,

Appenzell Innerrhoden,  Basel-Stadt and

Basel-Stadt and  Basel-Landschaft)

Basel-Landschaft)

See also

In Spanish: Historia de Suiza para niños

In Spanish: Historia de Suiza para niños

- Historiography of Switzerland

- History of the Grisons

- History of Zürich

- List of presidents of the Swiss Confederation

- Politics of Switzerland

- Postage stamps and postal history of Switzerland

General: