History of the Alps facts for kids

The valleys of the Alps have been home to people for a very long time. The special Alpine culture that grew there often involves moving animals (like cows or sheep) between different pastures depending on the season. This is called transhumance.

Today, the Alps are shared by eight countries: France, Monaco, Italy, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Austria, Germany, and Slovenia. In 1991, the Alpine Convention was created. This agreement helps manage this huge area, which is about 190,000 square kilometers (about 73,359 square miles).

Contents

Early History (Before 1200)

The Wildkirchli caves in the Appenzell Alps show that Neanderthal people lived there around 40,000 BCE. Later, during the Würm glaciation (a very cold period that ended around 11,700 years ago), the entire Alps were covered in thick ice.

Modern humans arrived in the Alpine region about 30,000 years ago. Scientists have found a special genetic marker (called Haplogroup K) in people from the southeastern Alps. This marker is thought to be about 12,000 years old.

Signs of transhumance (moving livestock seasonally) appeared during the Stone Age. In the Bronze Age, the Alps were a border between the Urnfield culture and Terramare culture.

The famous mummy known as "Ötzi the Iceman" was found in the Ötztal Alps. He lived around 3200 BC. By his time, most people in the Alps had stopped just hunting and gathering. They had started farming and raising animals. We're still not sure if they practiced transhumance back then.

The first written records about the Alps come from the Roman period. These records are mostly from Greek and Roman writers. We also have some carvings from local tribes like the Raetians, Lepontii, and Gauls. The Ligurians and Venetii lived on the edges of the Alps in the south.

The Rock Drawings in Valcamonica also date from this time. We know a few things about how the Roman emperor Augustus conquered many Alpine tribes. We also know about Hannibal's famous battles when he crossed the Alps with his army and elephants. Most local Gallic tribes joined Hannibal during the Second Punic War. Because of this, Rome lost control of much of Northern Italy for a while. Rome only fully conquered Northern Italy after defeating Carthage in the 190s BC.

Between 35 and 6 BC, the Alpine region slowly became part of the growing Roman Empire. The Tropaeum Alpium monument in La Turbie celebrates Rome's victory over 46 tribes in these mountains. After this, the Romans built roads over the Alpine passes. These roads connected Roman settlements in the south and north. This helped bring the people of the Alps into the Roman Empire's culture. The upper Rhône Valley became Roman after a battle in 57 BC. Aosta was founded in 25 BC as a Roman city. Raetia was conquered in 15 BC.

When the Roman Empire split and its Western part collapsed in the 4th and 5th centuries, power in the Alps returned to local leaders. Often, church areas called dioceses became important centers. In Italy and Southern France, dioceses in the Western Alps were set up early. But in the Eastern Alps, they were founded later and were usually much larger. New monasteries in the mountain valleys also helped spread Christianisation among the people.

During this time, the main political powers were north of the Alps. First, it was the Carolingian Empire, then later France and the Holy Roman Empire. German emperors, who were crowned by the Pope in Rome, had to cross the Alps with their groups between the 9th and 15th centuries.

In the 7th century, many Slavic people settled in the Eastern Alps. Between the 7th and 9th centuries, the Slavic principality of Carantania existed. It was one of the few non-Germanic states in the Alps. The Alpine Slavs (who lived in most of modern-day Austria and Slovenia) slowly became Germanized between the 9th and 14th centuries. The modern Slovenes are their descendants in the south.

The movement of the Alemanni people into the Alps from the 6th to 8th centuries is also not fully known. For big empires like the Frankish Empire and later the Habsburg monarchy, the Alps were important as a barrier, not just a landscape. The Alpine passes were very important for military reasons.

Between 889 and 973, a group of Muslim raiders from Fraxinetum (on the coast of Provence) blocked the Alpine passes. This stopped Christian travelers until they were driven out in 973. After that, trade across the Alps could start again.

It wasn't until the Carolingian Empire finally broke up in the 10th and 11th centuries that we can clearly see the local history of different parts of the Alps. This includes the Walser migrations in the High Middle Ages.

Later Medieval to Early Modern Era (1200 to 1900)

The French historian Fernand Braudel once called the Alps "an amazing range of mountains" because of their resources, organized communities, skilled people, and good roads. This strong human presence in the Alps grew during the High Middle Ages due to population growth and more farming.

At first, people in the Alps did both farming and animal raising. But from the Late Middle Ages onwards, cattle became more common than sheep. In some northern parts of the Alps, cattle farming grew so much that it completely replaced agriculture. At the same time, other types of trade between regions and across the Alps also grew. The most important pass was the Brenner Pass, which carts could use starting in the 15th century. In the Western and Central Alps, passes could only be used by pack animals until around 1800.

The formation of states in the Alps was influenced by nearby European conflicts, like the Italian wars (1494–1559). During this time, the social and political structures of Alpine regions changed in different ways. There were three main ways:

- Princely centralization: Where princes gained more power (Western Alps).

- Local-communal: Where local communities had more power (Switzerland).

- Intermediate: Where powerful nobility had a lot of influence (Eastern Alps).

Until the late 19th century, many Alpine valleys were still mostly focused on farming and raising animals. More people meant more intensive land use and more production of corn, potatoes, and cheese. The shorter growing season at higher altitudes didn't seem to be a problem until around 1700. But later, it became a big obstacle for farming compared to the lowlands, where land productivity grew quickly.

Within the Alps, there was a big difference between the western and central parts (which had many small farms) and the eastern part (which had medium or large farms). People started moving to cities in the surrounding areas even before 1500, often temporarily. Urbanization (the growth of cities) was slow within the Alps themselves.

Central Alps

In the Central Alps, the most important event on the northern side was the slow formation of the Old Swiss Confederacy from 1291 to 1516. This was especially true for the mountain cantons. The independent groups of the Grisons and the Valais only became full members of the Confederation in 1803 and 1815. The rich lands to the south were very appealing to both the Forest Cantons and the Grisons. So, they tried to gain, and did gain, various parts of the Milanese region.

The Gotthard Pass was known in ancient times, but it wasn't an important Alpine pass because the Schöllenen Gorge north of it was impassable. This changed a lot when the Devil's Bridge was built around 1230. Almost immediately, in 1231, the previously unimportant valley of Uri became a direct route to the Holy Roman Emperor. It became the main way to connect Germany and Italy. Also in 1230, a hospice (a place for travelers) was built on the pass for pilgrims going to Rome. This sudden importance for European powers in what is now Central Switzerland was a big reason for the formation of the Old Swiss Confederacy starting in the late 13th century.

In the 15th century, the Forest Cantons gained the Valle Leventina, Bellinzona, and the Valle di Blenio. They also held the Valle d'Ossola for a time. Blenio was added to the Val Bregaglia (which was given to the bishop of Coire in 960 by Emperor Otto I), along with the valleys of Valle Mesolcina and Val Poschiavo.

Western Alps

In the Western Alps (not including the area from Mont Blanc to the Simplon Pass, which followed the fate of the Valais), there was a long fight for control. This struggle was between the feudal lords of Savoy, the Dauphiné, and Provence. In 1349, the Dauphiné became part of France. In 1388, the county of Nice went from Provence to the House of Savoy. The House of Savoy also held Piedmont and other lands on the Italian side of the Alps.

From then on, the fight was between France and the House of Savoy. Slowly, France managed to push the House of Savoy back across the Alps, forcing it to become a purely Italian power.

A key moment in this rivalry was the Treaty of Utrecht (1713). By this treaty, France gave Savoy the Alpine areas of Exilles, Bardonnèche (Bardonecchia), Oulx, Fenestrelles, and Châtean Dauphin. In return, Savoy gave France the valley of Barcelonnette, which was on the western side of the Alps and part of the county of Nice. The final part of this long struggle happened in 1860. France gained the rest of the county of Nice and also Savoy. This made France the sole ruler on the western side of the Alps.

Eastern Alps

The Eastern Alps had been part of the Frankish Empire since the 9th century. From the High Middle Ages through the Early Modern era, the political history of the Eastern Alps was mostly about the rise and fall of the House of Habsburg. The Habsburgers originally came from the lower valley of the Aar, at Habsburg castle. They lost that area to the Swiss in 1415, just as they had lost other parts of what is now Switzerland before.

But they built a large empire in the Eastern Alps, where they defeated many smaller ruling families. They gained the duchy of Austria with Styria in 1282, Carinthia and Carniola in 1335, Tirol in 1363, and the Vorarlberg in pieces from 1375 to 1523. They also made smaller changes to their borders on the northern side of the Alps.

On the other side of the Alps, their progress was slower and less successful. They did gain Primiero quite early (1373), and in 1517, the Ampezzo Valley and several towns south of Trento. In 1797, they got Venetia itself. In 1803, they gained the church lands of Trento and Brixen (and Salzburg further north), plus the Valtellina region. In 1815, they gained the Bergamasque valleys, and the Milanese had been theirs since 1535.

However, in 1859, they lost both the Milanese and the Bergamasca to the House of Savoy. In 1866, they also lost Venetia. So, the Trentino was their main possession on the southern side of the Alps. When the future king of Italy gained the Milanese in 1859, Italy also got the valley of Livigno (between the Upper Engadine and Bormio). This is the only important part Italy holds on the non-Italian side of the Alps, besides the county of Tenda (gained in 1575, and not lost in 1860). After World War I and the end of Austria-Hungary, there were big changes to the borders in the Eastern Alps.

Modern History (1900 to Present)

Population Changes

We can estimate the population of the Alpine region in modern times. Within the area covered by the Alpine Convention, there were about 3.1 million people in 1500. This grew to 5.8 million in 1800, 8.5 million in 1900, and 13.9 million in 2000.

In the 16th century, scholars, especially those from cities near the Alps, started to become more interested in mountains. They were also curious about how the Earth was formed and how to understand the Bible. By the 18th century, a strong excitement for nature and the Alps spread across Europe. A famous example is the multi-volume book "Voyages dans les Alpes" (1779–1796) by Horace-Bénédict de Saussure. In his book, this naturalist from Geneva described his climb of Mont Blanc (4800 meters or 15,748 feet high) in 1787. This new interest also appeared in books, most famously in Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s popular romantic novel "Julie, ou la nouvelle Heloise" (1761). These cultural changes led to more interest in the Alps as a travel spot and set the stage for modern tourism. As Europe became more urbanized, the Alps stood out as a place of nature. During the time of colonial expansion, many mountains in Asia, Australia, and America were even named after the Alps.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, several important changes happened. First, the Alpine population grew at a different rate than the more active non-mountain areas. Second, people moving became much more common, often to places outside Europe. Starting in the early 20th century, some regions saw a depopulation (people leaving). This made the population distribution within the Alps even more uneven. City centers at lower altitudes grew a lot and became the most important and active places during the 20th century.

Economic Shifts

The economy also showed many signs of change. First, the farming sector started to lose importance. Farmers tried to survive by growing specialised crops in valley bottoms and increasing cattle-raising at higher altitudes. This big change was clearly due to the spread of industrialisation in Europe during the 19th century, which affected the Alps directly or indirectly.

On one hand, activities like iron manufacturing, which had been important earlier, faced limits because of transportation costs and the growing size of businesses. On the other hand, new opportunities for manufacturing appeared around the turn of the 20th century. This was largely thanks to electric power, one of the main inventions of the second industrial revolution. Plenty of water and steep slopes made the Alps a perfect place to produce hydroelectric power. So, many industrial sites appeared there.

However, it was definitely the service sector that saw the most important new development in the Alpine economy: the rapid rise of tourism. The first phase was dominated by summer visits. By about 1850, Alpine health resorts and spas expanded. Later, tourism started to shift to the winter season, especially after ski-lifts were introduced in the early 20th century.

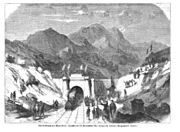

For a long time, transit traffic and trade had been a key part of the service sector in the Alps. But traditional routes and activities started to face strong competition from the building of railway lines and tunnels. Examples include the Semmering (1854), the Brenner (1867), the Fréjus/Mont-Cenis (1871), the Gotthard (1882), the Simplon (1906), and the Tauern (1909). In 2016, the 57 km (35 mile) long Gotthard Base Tunnel opened. With a maximum height of only 549 meters (1,801 feet) above sea level, it is the first flat, direct route through the Alpine mountains.

Overall, even though modern industry – tourism, railways, and later highways – brought opportunities to the Alps, it also caused negative effects, such as the human impact on the environment.

- Important Railway Routes Across the Alps

-

Gotthard Base Tunnel (2016), highest point: 549 m (1,801 ft)

Political History

Like other parts of Europe, the Alpine region was affected by the creation of nation states. This caused tensions between different groups and had consequences for border areas. In these regions, the power of the state was felt much more strongly than before. Borders became less open and now cut through areas that used to share a sense of community and trade. During World War I, the eastern Alpine region was a major center of the conflict.

After World War II, the Alps entered a new phase. At the same time, regional identities became stronger, and a common Alpine identity was built. A big step was made in 1991 with the signing of the Alpine Convention by all Alpine countries and the European Union. This process was strengthened by new cultural values for the Alps.

In the 19th century, there was a disagreement between those who saw the Alpine peaks as "sacred" (like John Ruskin) and modern mountain climbers (like Leslie Stephen), who called the Alps the "playground of Europe." In the 20th century, the mountains gained a clearly positive, iconic status. They were seen as places untouched by unwanted city influences like pollution and noise.

Tourism and Alpinism

The strong interest the British had in the Alps was connected to the general increase in the charm of this mountain range during the 18th century. However, there were also specific British reasons. Traditionally, many Englishmen were drawn to the Mediterranean. This was linked to the "Grand Tour" (a trip through Europe), which meant they had to cross Europe and the Alps to get there. The Alps changed from just a place to pass through to a tourist destination as more people and transport options became available. Also, with new sports being invented, the Alps became a place for experimental training. The Alps offered many mountain climbers a degree of difficulty that matched what they were looking for.

All these things together made Alpine tourism very important. It grew rapidly from the mid-19th century onwards and, despite ups and downs, never lost its importance. Railway companies, travel guides, travel stories, and travel agents all worked together to make the Alps a famous tourist destination. With Thomas Cook especially, the Alps appeared in tourist catalogs as early as 1861. They helped create a "truly international industry" of tourism. This industry built the necessary infrastructure: railway lines, hotels, and other services like casinos, promenades, and funiculars (cable railways).

British tourists "conquered" the Alps, and the mountains became more accessible. This happened with the eager help of local, regional, and national leaders, whether they were political, economic, or cultural. Leslie Stephen, in a popular book first published in 1871, called the Alps "the Playground of Europe." The book shows how incredibly successful the mountains were, but it also reflects the tensions that arose among visitors. There was a conflict between the "real enthusiasts" (who loved beauty) and the "flock of ordinary tourists" (who stuck to their usual habits and comforts).

During the 20th century, the Alps became part of the globalisation of tourism, which led to many more tourist destinations worldwide. However, these mountains kept a strong appeal for the British population. In fact, the British continued to see winter sports (like skiing, skating, bobsleigh, curling) as important reasons to travel and keep a unique culture alive. People like Gavin de Beer and Arnold Lunn showed this attitude through their many writings about the Alps from every possible angle. Indeed, the British have never stopped loving and being attracted to the Alps. This seems likely to continue, judging by the advertisements for major Alpine resorts in Sunday newspapers.

Linguistic History

The Alps are where French, Italian, German, and South Slavic languages meet. They also act as a place where old dialects can survive, like Romansh, Walser German, or Romance Lombardic. Some languages that used to be spoken in the Alps but are now extinct include Rhaetic, Lepontic, Ligurian, and Langobardic.

Because of the complicated history of the Alpine region, the native language and national feelings of the people don't always match the current international borders. The Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol region, which Italy took after World War I, has a German-speaking majority in its northern province of South Tyrol. You can find Walser German speakers in northern Italy near the Swiss border. There are also some French and Franco-Provencal-speaking areas in the Italian Aosta Valley. Plus, there are groups of Slovene-speakers in the Italian part of the Julian Alps, in the Resia Valley (where an old Resian dialect of Slovene is still spoken), and in the mountain area known as Venetian Slovenia.

See also

- Tauredunum event

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |