Kwakwakaʼwakw art facts for kids

Kwakwaka'wakw art is the amazing art created by the Kwakwakaʼwakw people who live in British Columbia, Canada. This art includes many different things like carvings from wood, sculptures, paintings, weavings, and special dances. You can see Kwakwaka'wakw art in their tall totem poles, detailed masks, wooden carvings, beautiful jewelry, and woven blankets. Their visual art often looks simple but very real, with a strong artistic touch. Dances are a big part of their many rituals and ceremonies. We know a lot about Kwakwaka'wakw art from stories passed down through generations, old objects found by archaeologists, and the work of artists who learned traditional ways.

Contents

Talented Artists of the Kwakwaka'wakw

Learning a craft is a very important part of growing up for young Kwakwaka'wakw people. Kids are encouraged to try different crafts. They often become apprentices to older, more experienced artists. Some artists even worked for chiefs, creating wooden gifts with family symbols to give out at special parties called potlatches.

In the late 1800s, trading brought a lot of wealth. This led to a "Golden Age" of potlatch art. However, the Canadian government made potlatches and other ceremonies illegal in 1884. This law made it harder for artists to create their work.

Later, after the ban was lifted, art became a way for people to earn a living again. Many talented carvers helped bring Kwakwaka'wakw art back to life. These included sculptors Dan Cranmer, Chief Willie Seaweed (1873–1967), Charlie James, Chief Mungo Martin (1879–1962), and his wife Abayah's great-grandsons Tony Hunt (born 1942) and Richard Hunt (born 1951). Mary Ebbets Hunt and Abayah Martin were also important artists who made many woven pieces. Traditionally, women were weavers, but Ellen Neel (1916–1966), Mungo Martin's niece, became a famous carver too.

Kwakwaka'wakw Art Style

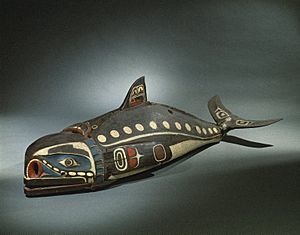

The art of the Kwakwaka'wakw people is similar to other styles found in Northwest Coast art, but it has its own special features. Kwakwaka'wakw art often uses deep cuts in the wood. They use paint only a little bit, mostly to highlight certain parts. Like other Northwest Coast art, Kwakwaka'wakw art uses a style called "punning" or "kenning." This means they fill empty spaces with smaller figures or designs. For example, you might see a face painted inside a whale fin.

Materials Used in Art

Kwakwaka'wakw artists use many natural materials. These include wood, horn, bark, shell, animal bone, and different colors of paint. For large projects, they prefer western red cedar because it grows a lot along the Northwest Coast. Yellow cedar is used for smaller items. Sometimes, wood is oiled for small carvings. Wood is also steamed to make it easier to bend.

Horns are used to make tools, especially cooking tools. Artists soften the horn by boiling it, then bend and carve it into the shape they want. For paint, they use red ochre, white paste made from burnt clamshells, and many other natural colors.

Tools for Creation

Traditionally, artists made their own tools for their personal use. These tools included adzes (a type of axe), carving knives, stone axes, stone hammers, and paintbrushes. Sometimes, brushes were made from porcupine hair. Later, the loom was used to weave blankets and curtains. Some tools were used for ceremonies and were decorated with carvings themselves.

Types of Kwakwaka'wakw Crafts

Kwakwaka'wakw crafts are mostly made from wood. They include a wide range of objects, such as masks, figures, rattles, storage boxes, food bowls, and large totem and house poles. Almost all of these crafts are painted in some way.

Amazing Masks

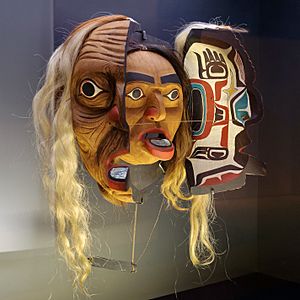

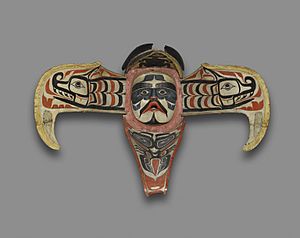

Masks were a very important part of Kwakwaka'wakw art and culture. They were essential in dances to show the character the dancer was playing. Because of this, there are many different kinds of masks. They show mythological beings, animals, forces of nature, and other humans. Some masks are decorated with feathers and "hair," often made from animal fur or strips of cedar bark. Here are a few important types of masks:

- Tsonokwa or Dzunuk'wa ("Wild Woman of the Woods" or "Giantess") masks have wild, messy hair and lips that stick out. She had wide eyes, facial hair, and sunken cheeks.

- Komokwa ("Wealthy one," "Chief of the Sea") masks are made to look like the sea. They have fish-like eyes, gill slits, scales, and sometimes a decorative seabird crest. Round holes or painted circles around the nose and cheek might represent air bubbles, octopus tentacle suckers, or anemones.

- Bookwus ("Wild man of the woods") masks have deep-set eyes, a hooked nose, and features like a human skull. The Bookwus lives near streams or forest edges and collects the souls of people who drown. His masks are usually green, brown, or black.

- Noohlmahl or Nulamal ("Fool") masks show funny, wild characters sent by the hamatsa. You can easily spot them by their very long nose with mucus and a humorous, twisted expression.

- "Sun" masks are usually round, with a hawk-like figure in the middle. Pieces of wood sticking out from the edges represent the sun's rays. Sun masks are often painted white, orange, and red. Sometimes, flattened copper is used on the mask's face.

- "Moon" masks often show a young male with features of a raven, like feathers or a beak. There are masks for both full and crescent moons. They can be completely round, round with a painted crescent, or simply a mask with a moon figure on top.

- "Echo" masks symbolize speech and ventriloquism. These masks are special because they have interchangeable mouthpieces. Each mouthpiece is a separate carving that fits into the mask's lip area, and each represents a being with a different voice.

- Transformation masks are complex and amazing masks built to show the two sides of mythological beings. The Kwakwaka'wakw were masters at making these. They are used in dances where the dancer can "open" the mask using strings. This reveals a second figure, usually a "human" mask hidden inside an animal shape. Transformation masks are made of several parts. The outer parts come together to form the animal or mythical shape, then they split open to show the inner mask.

Jewelry and Metalwork

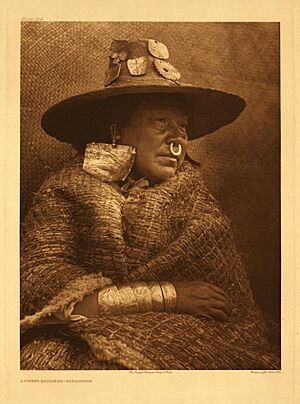

Kwakwaka'wakw jewelry included earrings, bracelets, necklaces, nose rings, lip piercings, and more. They used Abalone shells, stone, ivory, and wood to make jewelry. When Europeans arrived, they brought gold and silver, which were hammered into desired shapes. Silver and gold jewelry often had patterns and mythological figures carved into them. Wooden hairpins have also been found.

Copper pieces of different sizes were worn on the clothing of important people. "Copper" also refers to beaten copper objects, often engraved and shaped like a "T" or a shield. These copper pieces show great wealth. They can be broken into pieces and given away at potlatches. You can find images of shield-shaped coppers on Kwakwaka'wakw poles.

Woven Textiles

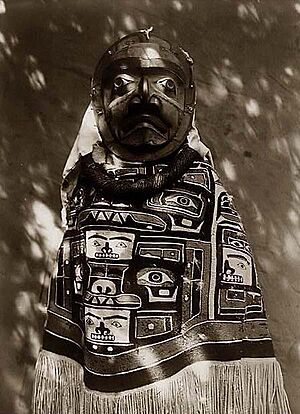

Textile arts in Kwakwaka'wakw culture include ceremonial curtains, dance aprons, blankets, and clothing. Weaving is usually done by women.

The ceremonial curtain, called a mawihl, is a painted curtain hung over the entrance to the dressing room used in dance ceremonies. Dancers could go behind the curtain to change costumes or as part of the performance. The mawihl was usually made from cotton and painted with the spirit of the dancing house.

The chilkat blanket was adopted by the Kwakwaka'wakw from the Tlingit and Tsimshian peoples to the north. These blankets are woven on a loom from shredded cedar bark and the wool of mountain goats. Chilkat blankets are heavy and very fancy. Each one takes almost a year to finish. Because of this, they are highly valued among the Northwest Coast peoples. The design is traditionally first painted by a man, and then woven by a woman following the design. Designs are usually patterned and detailed, showing a mix of ancestors and mythological figures. The edges of the chilkat blanket have flowing threads of wool. Mary Ebbets Hunt was a famous weaver of chilkat blankets. She was a Tlingit woman who married an Englishman working in the Fort Rupert area. She learned to weave from the northern tribes, and eventually, this technique was passed on to the Kwakwaka'wakw women.

Button blankets became popular when trade brought more blankets. Button blankets or cloaks are brightly colored, usually with a dark blue base and red fabric appliqué (pieces sewn on top). Borders and a central design, often a family crest, are decorated with abalone or mother-of-pearl buttons.

Dance aprons and leggings were also worn during ceremonies. The aprons were often decorated with small items like tiny coppers, puffin beaks, or deer hooves. These made pleasant sounds while dancing.

Totem and House Poles

The totem pole is one of the most complex and grand art forms in Kwakwaka'wakw culture. Poles are placed outside family houses. They show the family's crests, history, wealth, social rank, and special rights. The order of characters and symbols carved into a totem pole tells a story about past family events, ancestors, myths, and family symbols. The figure at the bottom is usually the most important. When a pole is first put up, its story is told in a semi-legendary way. Kwakwaka'wakw totems are made from red cedar and can be between fifteen and fifty feet tall. The carver's reputation depended on how good their work was.

The Kwakwaka'wakw style of totem poles uses more parts that stick out than other Northwest Coast totems. For example, limbs stretch out, beaks jut out, and wings are pushed away from the pole's body. Painting uses alternating dark and light colors to create contrast. Like other Kwakwaka'wakw art, their totems show a strong focus on realism.

House poles are posts that support the homes of important tribal members. The future homeowner orders them, and carvers from the tribe build them. Kwakwaka'wakw house poles are simpler and bolder in design. They tend to be thicker and well-rounded. House posts show ancestors, house symbols, and animals like the sea lion and grizzly bear. A front "entrance" pole might be used. These are different because they have a long opening at the bottom and do not support any part of the roof.

Small Carved Objects

The Kwakwaka'wakw carved a wide variety of smaller wooden objects. These included whistles, rattles, special storage boxes, figures, staffs, utensils, ceremonial knives, headdresses, headbands, and food bowls.

Painting and Graphic Art

Painting was traditionally used to decorate carvings and flat surfaces. The first types of Kwakwaka'wakw painting were designs for totems, masks, and textiles. When paper became available, artists started making graphic art and produced many notable paintings. Later, local groups asked artists like Ray Hanuse to paint buildings with Kwakwaka'wakw designs.

The Importance of Dance

Like other dancing groups of the Pacific Northwest, dance is a central part of Kwakwaka'wakw life. It is found at many important events and ceremonies. Dance is so important that each type must be carefully planned and prepared. Special tribe members are chosen to watch dances to make sure they are performed correctly. Mistakes or poorly done dances could mean losing social standing. The German anthropologist Franz Boas found a total of fifty-three different characters in Kwakwaka'wakw dance, each with a different role.

Tsetseka: The Supernatural Season

Tsetseka ("Supernatural season" or "Winter Ceremonial") is perhaps the most important dancing ritual among the Kwakwaka'wakw. The word comes from the Heiltsuk word for "shaman" and refers to winter. The entire winter season is seen as supernatural, and this is shown in every ritual performed during this time.

The tsetseka dance is carefully planned and staged by officials with special jobs. New dancers who are joining the ceremony are carefully prepared. They receive instructions on acting, dancing, and making the right sounds. Complex props and stage illusions are made ready, from hidden strings and tunnels for magic tricks to loud noises on the roof to pretend mythical birds are flying. The whole event goes beyond the dancing house. Acts are planned for new members to be initiated into the ceremony. For example, a new member might appear to arrive on a canoe but then seem to drown in an accident. Later, they would be "revived" with much celebration. The figure that drowned was actually a wooden carving used to represent the new member. During tsetseka, the entire Kwakwaka'wakw living space became a kind of live theater. Terror, drama, illusion, and comedy were all used to create the special atmosphere of the season.

The hamatsa ritual is the most important dance in the tsetseka season. The goal of the performance is to initiate a new person into a hamatsa dancer, which is the highest rank of dancer. Only individuals who have danced for twelve years through the previous three levels can try to achieve this. The dance needs many characters, takes four days to finish, and is full of ritual and drama. It is based on the legend of the hamatsa, terrible bird-like monsters that ate human flesh. In the ceremony, the new dancer is believed to be possessed by a hamatsa spirit. They disappear into the woods for four days. While possessed, the new dancer must dance and cry as if in a frenzy, acting wild and violent with the audience. After four days, the person is ritually calmed until they are "human" again. Achieving this state means the new dancer is accepted into the dancing society as a full member.

Modern Kwakwaka'wakw Art

David Neel (born 1960), who is the grandson of carver Ellen Neel, is a modern Kwakwaka'wakw painter, photographer, printmaker, and multimedia artist. His work shows that Northwest Coastal art can address current social and political issues. For example, he creates prints and masks that talk about land conflicts, radiation, oil spills, clear-cutting forests, and too many people.

Famous Kwakwaka'wakw Artists

- Calvin Hunt, woodcarver

- Henry Hunt, woodcarver

- Richard Hunt, woodcarver

- Mungo Martin, woodcarver

- Beau Dick, artist, woodcarver

- David Neel, multimedia artist

- Ellen Neel, woodcarver

- Willie Seaweed, woodcarver

See Also

- Chilkat weaving

- Transformation mask

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |