London in World War II facts for kids

| 3 September 1939 – 2 September 1945 | |

Heinkel He 111 bomber over the Surrey Commercial Docks on 7 September 1940

|

|

| Preceded by | London (1900-1939) |

|---|---|

| Followed by | Modern London (from 1945) |

| Monarch | George VI |

London was the capital of the United Kingdom and the British Empire during World War II. The war lasted from September 3, 1939, to August 15, 1945. In 1939, London was the world's largest city, with 8.2 million people. It was a main target for German attacks. The German Air Force (Luftwaffe) bombed London in 1940. Later, the city was hit by V-1 flying bombs and V-2 rockets.

About 18,688 Londoners died during the war. Around 1.5 million people lost their homes. Also, 3.5 million homes and 836,127 square meters of office space were damaged or destroyed.

Contents

Getting Ready for War

London started preparing for war as early as 1935. Air Raid Precautions (ARP) teams were set up. These teams helped with firefighting, rescue, and building repairs. The Women's Voluntary Service (WVS) also formed in 1938. They helped protect against air raids.

Blackouts and Gas Masks

At night, London had "black-out" rules. This meant all lights had to be off or covered. This made it hard for enemy planes to see the city. Street lamps, car headlights, and even cigarettes had to be hidden. In 1938, Londoners received gas masks. These were to protect against possible mustard gas attacks.

City Defenses

London had three rings of defense. The outer rings had trenches, bunkers, and roadblocks. The inner ring was guarded by the army. Special gates were put in the London Underground tunnels. These stopped the river from flooding the tunnels. Large Barrage balloons floated above London. They forced enemy bombers to fly higher, making it harder to aim.

Protecting Valuables

Museums and libraries moved important items to the countryside. The Natural History Museum sent its collections away. The British Museum moved 30,000 rare books to Wales. The National Gallery moved all its paintings. Aldwych Station was used to store treasures. These included the Parthenon Marbles. Westminster Abbey's treasures were moved. Its tombs were protected with 60,000 sandbags.

Animals in Wartime

The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) put down 400,000 pets. This happened in the first week of the war. It was done to save food. All venomous animals at London Zoo were killed. This was to prevent them from harming people if they escaped. Some large animals were moved to other zoos.

BBC Broadcasts

On September 1, 1939, the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) stopped TV broadcasts. They only broadcasted radio on one channel.

Moving People to Safety

The London County Council (LCC) started moving children in 1938. The first group included nursery and disabled children. But war did not start right away, so plans were stopped.

On September 1, 1939, the evacuation started again. Most children left London by train. Some left by boat. Richer families drove their children away.

Less than half of London parents used the plan. When children arrived, some families were split up. Some children were placed with unsuitable guardians. Many evacuees returned home quickly. By mid-October, 50,000 mothers and children were back. Schools were often closed or teachers had left. By January 1940, only 15 schools were open in the LCC area.

Not just children were evacuated. Hospitals moved patients. The government moved thousands of workers. Many people also left London on their own. By March 1940, the population of Chelsea had dropped a lot.

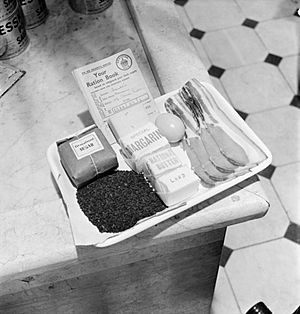

Food and Rationing

At the start of the war, prices for goods went up. The government set price controls in November 1939. Rationing rules began with petrol in September 1939. Then it included food and clothing. People sometimes bought a lot of goods before new rules started. With less petrol, London's roads became empty. Buses and taxis were taken out of service.

Rich people could still eat well at restaurants. But in May 1942, restaurants could not charge more than five shillings for a meal. This stopped people from spending too much. Restaurants made smaller, simpler dishes. The London County Council opened "British Restaurants". These offered cheap, healthy food in nice places.

Food Shortages and New Habits

Some foods became impossible to get. Bananas, honey, and certain spices were gone. Matches and kindling wood were also hard to find. Homemade alcohol became popular, but it could be dangerous. Feeding pets human food was banned. Even dog food was scarce.

People were encouraged to try new foods. Catfish and horse meat were served. Rook pie was also eaten. Londoners started gardening to grow vegetables. Public parks became allotments. The Tower of London moat grew food. The British Museum forecourt had peas and onions. Many people kept chickens or joined pig clubs. Sheep were even kept in Kensington Gardens.

Black Market and Waste

Some people bought rationed goods illegally on the black market. One Italian restaurant served steaks hidden under spinach. Others gave rationed goods as gifts. This was called the "grey market."

Wasting food was strongly disliked. Some Londoners were punished for feeding bread to birds. Councils taught people how to cook without fat or sugar. They also taught how to make cheap meals. Londoners were also asked to save paper. Newspapers became much shorter. In 1943, Londoners recycled 5.5 million old books.

Bombing Attacks

Before the war, people knew London would be bombed. The government expected many casualties. Mass graves were even dug in Fulham.

At first, German leader Adolf Hitler ordered no attacks on London. But on August 24, 1940, bombs fell on London. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered attacks on Berlin in return.

The areas hit hardest were the City of London, Holborn, and Stepney. They received over 600 bombs per 4 square kilometers. Other heavily hit areas included Bermondsey and Westminster.

The Blitz Begins

Bombing started seriously on September 7, 1940. This was the start of the "Blitz." It was called "Black Saturday." The Surrey Commercial Docks caught fire. Over 1,000 firefighters worked all night. Half a mile of shoreline burned down. London was bombed for 57 nights in a row.

Authorities worried about poison gas bombs. Pillar boxes were painted with yellow squares. These would change color if gas was present. Londoners were told to carry gas masks. But many stopped carrying them over time.

On December 29, 1940, bombing was so heavy it was called the "Second Great Fire of London". Many firewatchers were off duty. Fires spread quickly. The City of London was badly hit. St. Paul's Cathedral was a key target. A famous photo, St. Paul's Survives, showed the dome surrounded by smoke. It became a symbol of British strength.

The last major Blitz raid was on May 10, 1941. It killed 1,436 people. Buildings like the House of Commons and Westminster Abbey were hit. The Blitz dropped 20,000 tons of bombs on London. It killed 20,000 people and injured 25,000.

V-1 and V-2 Attacks

On June 13, 1944, London was hit by the first V-1 rockets. Londoners called them "doodlebugs." These were pilotless bombs fired from France. They flew at 560 km/h. The first one killed six people. Over 900 V-1s hit London in 81 days. When the engine stopped, people had about twelve seconds to find cover.

When Allied forces captured French launch sites, V-1 attacks dropped. Then, on September 8, 1944, the first V-2 rocket hit London. These rockets came from Holland. They could not be heard or tracked. The worst V-2 attack killed 160 people at a Woolworth's shop.

In total, 963 V-1s and 164 V-2s hit London.

Air-Raid Shelters

The government was slow to provide strong underground shelters. They feared people would not leave them. Early public shelters were weak trenches. One was hit in Kennington Park, killing many.

People were told to use reinforced rooms at home. Or they could use Anderson shelters in their gardens. But many poorer Londoners had no gardens or strong homes. Public shelters opened in church crypts, basements, and under railway arches.

Some Londoners used London Underground stations for shelter. This was first banned, then allowed. New deep-level shelters were built. They had toilets, washing facilities, and bunks. Some even hosted concerts. However, using the Underground was not always safe. Bombs hit stations like Bounds Green and Balham station, killing many. The worst civilian disaster happened at Bethnal Green in 1943. A panicked crowd on the stairs led to over 170 deaths, even without a bomb hit.

Many Londoners did not seek shelter at all. A survey found that 51% of families did not use shelters.

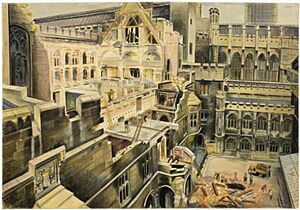

Building Damage

Many famous buildings were damaged. The John Lewis department store was hit in 1940. St. James' Piccadilly church was badly damaged. The Twinings tea shop on the Strand was destroyed.

The British Museum was hit several times. In May 1941, 240,000 books were damaged by fire and water. The Palace of Westminster was also hit. The House of Commons chamber was unusable. So, meetings moved to other places. Westminster Abbey was also damaged.

Buckingham Palace was hit at least nine times. The worst was on September 13, 1940. The Queen said, "Now I can look the East End in the face." This was because working-class areas were often hit harder.

Many buildings still show shrapnel marks. These include the Victoria & Albert Museum and the Tate Britain gallery. Some churches were left in ruins and became public gardens. The church of St. Mary Aldermanbury was rebuilt in the USA.

Wartime Leaders in London

Many British leaders worked in London. This included Prime Ministers Neville Chamberlain and Winston Churchill. Churchill wanted a "War Room" to direct the war. Construction began in 1938 for the Churchill War Rooms. They were first used in August 1939. Churchill said, "This is the room from which I'll direct the war."

The War Rooms had a Cabinet Room for meetings. A Map Room tracked the war 24 hours a day. There were also bedrooms and offices. On August 14, 1945, Japan surrendered. The next day, the rooms were cleared. Today, they are a museum. The War Cabinet also met at the closed Down Street Underground station.

The War Office on Whitehall was the army's headquarters. The Admiralty Building was the navy's headquarters. Churchill became the head of the Admiralty in 1939. The navy protected merchant ships and cleared German sea mines. They also helped rescue over 300,000 troops from Dunkirk.

The Ministry of Information was based in Senate House. This was the government's propaganda department.

Early United Nations

London also saw the start of the United Nations (UN). In 1941, European governments and Commonwealth countries signed the "Declaration of St. James's Palace." They wanted to work together for peace and security.

Secret Intelligence

The Security Service, or MI5, moved its headquarters to Wormwood Scrubs prison. They grew from 3 officers to 102. MI5 ran a "double-cross spy ring." Captured German spies were turned to work for Britain. They sent false information to Germany. This helped trick Germany about Allied invasion plans.

The Secret Intelligence Service, MI6, was based at 54 Broadway. They gathered information on enemy nations. They had a code-breaking team at Bletchley Park. They broke German codes, including the Enigma ciphers.

MI9 helped Allied soldiers escape from occupied Europe. They questioned returning soldiers. Some places used for questioning were reported to have harsh conditions.

Special Operations Executive

The Special Operations Executive (SOE) trained agents. These agents worked in enemy territory. Their mission was to "set Europe ablaze." They used buildings around London. Their headquarters was at 64 Baker Street. They recruited Londoners like Violette Szabo. Their Camouflage Section hid radios and other gear inside everyday objects. The Make-Up Section helped agents change their appearance. The Signals Directorate handled codes and talked to agents.

The French section of the SOE briefed new agents in a flat. This was to keep their main headquarters secret.

Changes to London's Spaces

Many places in London changed during the war. Selfridges department store hosted secret American encryption machines. These allowed Churchill and US President Franklin D. Roosevelt to talk securely. Grosvenor Square became a station for a barrage balloon.

King George VI had part of Buckingham Palace gardens turned into a firing range. He practiced shooting for a possible invasion. Many London parks had anti-aircraft guns. Regent's Park was used to detonate unexploded bombs. Londoners were asked to grow food. Many public areas became allotments. This included the Tower of London moat.

A large "citadel" was built next to the Admiralty Building. It was a safe place for naval officers to work. It was also a last defense against invasion.

Many wrought-iron railings around London houses were melted down. They were used to make planes, tanks, and ammunition. After the war, there was a debate about replacing them. Some people liked that green spaces were now open to everyone.

The National Gallery was empty of paintings. Its director invited pianist Myra Hess to give concerts there. These lunchtime concerts were very popular. The gallery also started showing one painting a month.

People Arriving from Overseas

Many Germans and Austrians in London were arrested. They were sent to camps. This included both Nazi supporters and Jewish refugees. There were more arrests in May 1940. When Italy joined the war, many Italian Londoners were arrested. Italian restaurants put up signs saying they were "100 per cent patriotic British."

Soldiers from many countries came to London. Polish, French, and Czech soldiers were common. A mosque was built for Muslim soldiers from the British Empire.

In 1941, German Deputy Fuhrer Rudolf Hess flew to Scotland. He was captured and briefly held in the Tower of London.

Refugees in London

Before the war, 29,000 German refugees came to Britain. Most lived in London. Some Londoners were suspicious of them.

The Kindertransport program brought 9,354 German, Austrian, and Czech children to Britain. Most were Jewish. They came to escape Nazi persecution. Children arrived at Liverpool Street Station in London. Foster families collected them. Those without families went to refugee camps. Later, some were held on the Isle of Man. After the war, many tried to find their parents. There are two statues for the Kindertransport at Liverpool Street Station.

Many European royals fled to London. This included the kings and queens of Norway, the Netherlands, and Poland. Prince Peter of Yugoslavia and Princess Alexandra of Greece married in London. Their son, Crown Prince Alexander, was born at Claridge's Hotel. Churchill declared the hotel room Yugoslavian territory for 24 hours.

European governments also moved to London. The Belgian and Polish governments set up in London. French commander Charles de Gaulle lived at the Connaught Hotel. He led the Free French Forces from London. He called on French citizens to resist Germany.

Americans in London

Even before the US joined the war, many Americans were in London. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, their numbers doubled. By June 1944, US troops had many buildings in London. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Allied commander, was based in London. Grosvenor Square was nicknamed "Little America" because so many American officers were there.

The Savoy Hotel was popular with American journalists. An American Red Cross club called "Rainbow Corner" opened on Piccadilly. It served American soldiers things hard to get in Britain, like doughnuts. It was open 24 hours a day. British women often found American soldiers exciting. They had smart uniforms, access to rationed goods, and Hollywood accents.

Some Londoners were suspicious of Americans. Rumors spread about fights. Americans were better paid and fed than British soldiers. This caused some resentment.

There were also issues with racial segregation. White American officers from the South expected segregation. British authorities tried not to offend them. A note advised white women not to date black soldiers.

Women in New Roles

Women could join the army, navy, and air force auxiliary branches. But their roles were limited. The Home Guard was a citizen militia. At first, it did not allow women. MP Dr. Edith Summerskill argued for women to join. She wanted them to have equal rights. Some women formed unofficial groups to train.

Finally, in April 1943, women could officially join the Home Guard. But only in small numbers and in unarmed roles.

Women were greatly needed in many jobs. They replaced men who joined the armed forces. They worked in factories, as bus conductors, and bank tellers. At first, managers resisted them. But women were gradually accepted. By the end of the war, women worked in many services. These included the police, fire, and ambulance services.

In 1941, Britain became the first country to draft women. They were conscripted into the armed forces and industry. As the war went on, married women were also needed. Women demanded more nurseries so they could work. By the end of the war, over 75% of married women in London did war work.

Morale and "Blitz Spirit"

Many believe Londoners stayed strong and united during the Blitz. The government promoted this image. A film called London Can Take It! showed Londoners with "no fear and no panic." Londoners put defiant signs on their bombed homes. Some showed humor. One woman joked about finding her neighbor "half one side of 'er door and 'alf the other." A Hungarian doctor praised the discipline of Londoners. He said they showed no hysteria. Mental illness reports actually went down during the war.

However, the war did affect Londoners. Many suffered from lack of sleep. Some reported hearing air-raid sirens when there were none. By April 1941, an American journalist noted that the "we-can-take-it stuff" was gone.

Some Londoners turned against their Jewish neighbors. They spread false rumors. Studies showed that Jewish people did not dominate shelters or the black market.

Working-class Londoners felt their homes were hit hardest. Their areas had important targets like factories. Their houses were less strong. They also had fewer places to escape to. Some protested, demanding shelter in fancy hotels.

War Artists

The War Artists' Advisory Committee (WAAC) hired artists. Their job was to record the war. Many artists worked in London. William Roberts drew workmen at the Woolwich Arsenal. Roland Vivian Pitchforth painted Air-Raid Precautions in London. Leonard Rosoman was a fireman. He painted "A House Collapsing on Two Firemen," showing his colleagues before they died. Graham Sutherland recorded bomb damage in the City. Henry Moore sketched people sleeping in London Underground stations.

Artists also faced the Blitz. Some had their studios destroyed. The WAAC told artists what they could paint. They avoided scenes of panic or violence. But they encouraged pictures of bombed buildings. Photographers like Bill Brandt also recorded Londoners in shelters.

After the War

On VE Day, the royal family and Churchill appeared at Buckingham Palace. Crowds cheered.

Families usually buried their own dead. But if not possible, the local council did. Most London boroughs had mass graves. They built memorials after the war.

The war caused many people to leave inner London. Some did not return. The population of Stepney dropped by over 40%. People demanded that councils use empty houses for the homeless. Activists moved homeless people into empty houses. The new Labour government gave councils more power to take over abandoned homes.

After the war, many emergency stretchers were recycled. They became fences for council estates. Some of these "stretcher railings" can still be seen today. Many memorials were built in London. They honor those who worked and died during the war.

See also

| Misty Copeland |

| Raven Wilkinson |

| Debra Austin |

| Aesha Ash |