Memorial tablets to the British Empire dead of the First World War facts for kids

Between 1923 and 1936, the Imperial War Graves Commission placed special memorial tablets in churches and cathedrals across France and Belgium. These tablets honored the soldiers from the British Empire who died in the First World War. They were put in towns where British or Empire troops had stayed during the war.

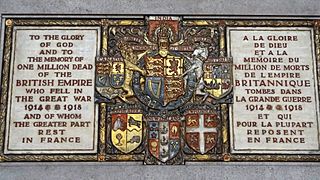

The very first tablet was placed in Amiens Cathedral in 1923. It remembered 600,000 soldiers from Britain and Ireland. Later tablets had a new design. They showed the British Royal Coat of Arms along with symbols for India and other parts of the Empire: South Africa, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Newfoundland. The famous writer Rudyard Kipling wrote the words on these tablets. They spoke of "a million dead" from the Empire.

These tablets were made by Reginald Hallward and designed by H. P. Cart de Lafontaine. Twenty-eight were put up in total, mostly in France and some in Belgium. The words were in English and French in France, and English and Latin in Belgium. Important people like members of the royal family and army generals helped unveil them.

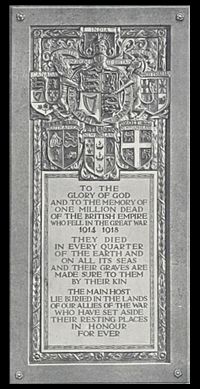

A similar tablet was unveiled in Westminster Abbey in 1926. It remembered soldiers buried in the "lands of our Allies." Copies of this Westminster tablet were sent to churches in Canada (Hamilton and Vancouver) and Iraq (Baghdad). Other copies are in museums in France (Delville Wood), Australia (Fremantle), and the UK (Liverpool).

Contents

Why Were These Tablets Made?

The Imperial War Graves Commission was created in 1917. After World War I ended in 1918, the Commission planned how to remember the soldiers who died. They were in charge of war graves. But it was not clear who would create bigger memorials for all soldiers.

At first, different groups handled different types of memorials. But by 1921, it was decided that the Imperial War Graves Commission would be responsible for all general war memorials. One idea they took on was to place special tablets in French cathedrals. These cathedrals had a special connection to British troops during the war.

A team from the Commission worked on this project. It included Lieutenant General Sir George Macdonogh, Sir Herbert Creedy, the writer Rudyard Kipling, and the Commission's founder, Fabian Ware. The tablets were designed by architect H. P. Cart de Lafontaine and made by sculptor Reginald Hallward.

Cart de Lafontaine spoke French well. He talked with the church leaders to arrange the tablet placements. The plan grew to include cathedrals in Belgium too. Some churches were badly damaged in the war, so the tablets had to wait until repairs were done. The team also had to figure out the best spot for each tablet inside the cathedrals. Some tablets were designed to be horizontal instead of vertical to fit the space.

The first tablet, made for Amiens Cathedral, showed the Royal Coat of Arms. It mentioned the armies of Great Britain and Ireland.

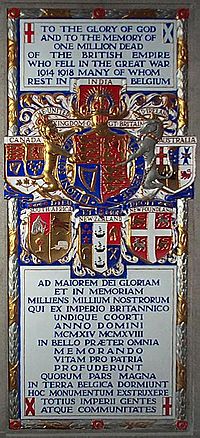

All the later tablets had a different design. They included symbols from all the dominions (countries like Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and Newfoundland) and India. This standard design had the Royal Coat of Arms surrounded by the shields of these five Dominions. The Indian Empire was shown by the symbol of the Order of the Star of India. The words on the tablets included mottos from the Royal Coat of Arms: Honi soit qui mal y pense and Dieu et mon droit. The tablets were made of gilded (gold-colored) and colored gesso (a type of plaster) set in stone. They also had a border with carved roses. The Westminster tablet is about 5 feet 10 inches tall.

- Symbols of the Dominions

Where Were the Tablets Placed?

The tablets were placed in many cathedrals and churches in France, Belgium, and other countries between 1923 and 1936. Here are some of the places and dates they were unveiled:

| Cathedral or church | Town or city | Country | Date unveiled | Unveiled by |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amiens Cathedral | Amiens | France | 9 July 1923 | Duke of Connaught |

| Notre Dame | Paris | France | 7 July 1924 | Prince of Wales |

| Le Mans Cathedral | Le Mans | France | 28 January 1925 | Horace Smith-Dorrien |

| Rouen Cathedral | Rouen | France | 25 February 1925 | Nevil Macready |

| Orléans Cathedral | Orléans | France | 23 July 1925 | William Birdwood |

| Marseille Cathedral | Marseille | France | 24 July 1925 | William Birdwood |

| Nancy Cathedral | Nancy | France | 4 September 1925 | Thomas Dodds |

| Beauvais Cathedral | Beauvais | France | 7 September 1925 | Victor Gordon |

| Nantes Cathedral | Nantes | France | 9 September 1925 | Victor Gordon |

| Meaux Cathedral | Meaux | France | 11 November 1925 | Sidney Clive |

| Bayeux Cathedral | Bayeux | France | 17 December 1925 | Horace Smith-Dorrien |

| Westminster Abbey | London | United Kingdom | 19 October 1926 | Prince of Wales |

| St Waudru Collegiate Church | Mons | Belgium | 11 November 1926 | Nevil Macready |

| St Rumbold's Cathedral | Mechelen | Belgium | 26 March 1927 | George Macdonogh |

| Notre-Dame de Boulogne | Boulogne | France | 2 April 1927 | Nevil Macready |

| Senlis Cathedral | Senlis | France | 10 July 1927 | Nevil Macready |

| Laon Cathedral | Laon | France | 16 July 1927 | William Pulteney |

| St Michael and St Gudula | Brussels | Belgium | 22 July 1927 | Douglas Haig |

| Church of the Ascension | Hamilton | Canada | 2 October 1927 | John Morison Gibson |

| Église Saint-Maurice | Lille | France | 22 October 1927 | Richard Haking |

| Reims Cathedral | Reims | France | – – – | Alexander Godley |

| Soissons Cathedral | Soissons | France | – – – | William Pulteney |

| Saint-Vaast Church | Béthune | France | – – – | Edward Bulfin |

| Cambrai Cathedral | Cambrai | France | – – – | – – – |

| Saint-Quentin Basilica | Saint-Quentin | France | – – – | – – – |

| St George's Church | Baghdad | Iraq | – – – | – – – |

| Cathedral of Our Lady | Antwerp | Belgium | 16 June 1928 | George Dixon Grahame |

| Saint-Omer Cathedral | Saint-Omer | France | 21 October 1928 | Nevil Macready |

| Christ Church Cathedral | Vancouver | Canada | 11 November 1928 | Robert Randolph Bruce |

| Noyon Cathedral | Noyon | France | 11 October 1930 | George Macdonogh |

| St Martin's Cathedral | Ypres | Belgium | 26 May 1931 | Charles Harington |

| Arras Cathedral | Arras | France | 10 May 1936 | Duff Cooper |

Amiens Cathedral: The First Tablets

Amiens Cathedral is a very large church in France. After the war, many groups wanted to put memorials there. Eleven memorials are listed near the cathedral's south door. Six of these remember British or Dominion troops, including the very first Commission tablet.

The first memorial was for the Royal Canadian Dragoons. It was dedicated in 1919. Then came a tablet for the Australian Imperial Force in 1920. A tablet for South African forces was suggested by their Prime Minister. A tablet for Newfoundland soldiers was unveiled in 1922. The main Commission tablet was unveiled in 1923 by Prince Arthur. Finally, a tablet for New Zealand soldiers was unveiled in 1923.

The letters A.M.D.G. stand for a Latin phrase meaning "To the Greater Glory of God." The inscription mentions the Somme Offensive of 1916, the defense of Amiens in 1918, and the final push to victory in 1918. A copy of this Amiens tablet is at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission headquarters in the UK.

- Other Amiens Memorial Tablets

Tablets in France

The first standard tablet in France was unveiled at Notre Dame de Paris in 1924. The Prince of Wales (who later became King Edward VIII) unveiled it. Many French leaders were there too. The tablet was covered by a British flag. After it was unveiled, the Prince gave a message from King George V to the French President.

Many similar tablets were unveiled in French cathedrals in the mid-1920s. The tablet at Rouen Cathedral was placed on the north wall of the chapel for Joan of Arc. General Nevil Macready unveiled it in 1925. The Archbishop of Rouen spoke about the long history between Normandy and England. Macready ended his speech by saying, "Glory to Joan of Arc! Glory to our dead!"

The tablet at Arras Cathedral was the last one to be put up in France, in 1936. Its unveiling was delayed because the cathedral needed repairs after the war. Important people from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and India were there. The British ambassador and French government officials also attended.

A copy of the standard French tablet is also displayed at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission headquarters in the UK.

- Other French Memorial Tablets

Tablets in Belgium

The first tablets in Belgium were unveiled in Mons and Mechelen in 1926 and 1927. Then came the tablet in Brussels at the Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula in 1927. This was just before the famous Menin Gate memorial was unveiled in Ypres. Earl Haig unveiled the Brussels tablet.

Many Belgian and British leaders were at the Brussels ceremony. Earl Haig gave a speech in French. He honored the Empire's dead and the brave Belgian soldiers who fought at the Battle of Liège. Two more tablets were unveiled in Belgium: in Antwerp in 1928 and in Ypres in 1931. The Ypres tablet was delayed because St Martin's Cathedral needed to be rebuilt.

The tablets in Belgium have words in English and Latin. This was decided with the Belgian church leaders. Latin was used instead of the two official languages of Belgium. The Latin text is not a direct translation of the English.

Westminster Abbey Tablet

The tablet for Westminster Abbey in London looked like the others. But it had different words. It was unveiled in 1926. The Prime Ministers from the Dominions were in London for a big meeting, so they attended. The tablet was displayed in the Abbey's main area. Many important people were there, including war veterans who had lost their sight.

The Prince of Wales unveiled the tablet. He had also served in the war. He said: "I unveil this tablet in honour of our comrades, from every land under the Crown, who fell in the Great War. Time cannot dim our remembrance of them." He also thanked the Allies for giving land for the graves. After a short service, a wreath was laid, and the hymn O Valiant Hearts was sung.

The Westminster tablet was later moved to the Chapel of the Holy Cross, also called St George's Chapel. This chapel was dedicated to those who died in the war. It is near the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior. Every year since 1933, flowers from Commission cemeteries in Belgium and France are laid at the tablet.

Fabian Ware, the Commission's founder, said these tablets were made so that "the total losses of the British Empire might thus be visibly recorded." He saw them as a symbol of the British Commonwealth nations working together.

After the Second World War, the words on the Westminster tablet were changed to include those who died in that war. The tablets in Belgium and France were not changed.

Copies and Later History

After the Westminster Abbey tablet was unveiled, people asked for copies. Some full-size copies were made for churches. Smaller color prints were given to veteran groups. For example, a print is in Liverpool, UK, and another in Fremantle, Australia. A copy of the standard French tablet is at the Delville Wood Memorial museum in France.

Two copies of the Westminster tablet are in Canada. One is in the Church of the Ascension in Hamilton, Ontario. It was unveiled in 1927. The other is in Christ Church Cathedral in Vancouver. It was unveiled in 1928 on the tenth anniversary of the end of World War I. A copy was also put in St George's Anglican Church in Baghdad, Iraq, in the 1930s.

Like the original tablets, the copies sometimes had their words updated after World War II. The Vancouver tablet was updated to include the Second World War (1939-1945) and the Korean War (1950-1953).

Over the years, some tablets in France and Belgium needed repairs. Some were damaged by dampness or during the Second World War. Reginald Hallward's daughter, Patricia Hallward, made the replacement tablets. The tablet in St George's Anglican Church in Baghdad was damaged by shrapnel during the war in Iraq in 2003. Parts of its words were damaged, but the beginning and end were still readable.

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |