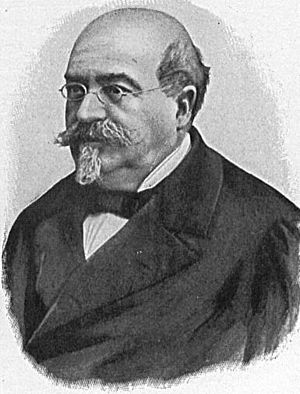

Mihail Kogălniceanu facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Mihail Kogălniceanu

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Prime Minister of Romania | |

| In office October 11, 1863 – January 26, 1865 |

|

| Monarch | Alexandru Ioan Cuza Carol I of Romania |

| Preceded by | Nicolae Kretzulescu |

| Succeeded by | Nicolae Kretzulescu |

| Foreign Affairs Minister of Romania | |

| In office April 27, 1876 – July 23, 1876 April 3, 1877 – November 24, 1878 |

|

| Preceded by | Dimitrie Cornea Nicolae Ionescu |

| Succeeded by | Nicolae Ionescu Ion C. Câmpineanu |

| Internal Affairs Minister of Romania | |

| In office October 11, 1863 – January 26, 1865 November 16, 1868 – January 24, 1870 November 17, 1878 – November 25, 1878 July 11, 1879 – April 17, 1880 |

|

| Preceded by | Nicolae Kretzulescu Anton I. Arion C. A. Rosetti Ion Brătianu |

| Succeeded by | Constantin Bosianu Dimitrie Ghica Ion Brătianu Ion Brătianu |

| Personal details | |

| Born | September 6, 1817 Iași, Moldavia |

| Died | July 1, 1891 (aged 73) Paris, France |

| Nationality | Moldavian, Romanian |

| Political party | National Liberal Party |

| Spouse | Ecaterina Jora |

| Profession | Historian, journalist, literary critic |

| Signature |  |

Mihail Kogălniceanu (born September 6, 1817 – died July 1, 1891) was an important Romanian leader. He was a liberal statesman, a lawyer, a historian, and a writer.

He became Prime Minister of Romania on October 11, 1863. This was after the union of Moldavia and Wallachia in 1859, under Prince Alexandru Ioan Cuza. Later, Kogălniceanu also served as Foreign Minister and Interior Minister under Prince Carol I.

Mihail Kogălniceanu was one of the most influential Romanian intellectuals of his time. He started his political journey working with Prince Mihail Sturdza. He also managed the Iași Theater and published several magazines.

He was a key figure in the 1848 Moldavian revolution. He wrote its main document, Dorințele partidei naționale din Moldova. After the Crimean War (1853–1856), he helped create laws to end Roma slavery. He also worked to unite the Romanian lands.

Kogălniceanu helped Prince Cuza become ruler. He then pushed for laws to remove old noble titles and take over land owned by monasteries. His efforts to change land ownership led to a conflict. This caused Prince Cuza to take power by force in May 1864. However, Kogălniceanu resigned in 1865 after disagreements with the prince.

Ten years later, he helped form the National Liberal Party. He played a big part in Romania joining the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. This war led to Romania's independence. He also helped Romania gain and develop the Northern Dobruja region. In his later years, he was a respected member and president of the Romanian Academy. He also briefly represented Romania in France.

Contents

- Biography

- Early Life and Education

- Early Publications and Theater Work

- The 1848 Revolution

- Reforms Under Prince Ghica

- Uniting the Principalities

- Land Reform and Monasteries

- Cuza's Rule and Later Reforms

- Carol I and the National Liberal Party

- Romania's Independence

- Congress of Berlin and Northern Dobruja

- Final Years

- Views

- Legacy

- Images for kids

- See also

Biography

Early Life and Education

Mihail Kogălniceanu was born in Iași, Moldavia. His family, the Kogălniceanu family, were Moldavian boyars (nobles). His father was Ilie Kogălniceanu. His great-grandfather, Constantin Kogălniceanu, signed a document in 1749 that ended serfdom (a type of forced labor) in Moldavia. Mihail's mother, Catinca Stavilla, was from a Romanian family in Bessarabia. He was proud that his family's roots were purely Romanian.

There was some confusion about his birth year. He later clarified that he was born on September 6, 1817. His godmother was Marghioala Calimach, a noblewoman connected to the Sturdza family.

Kogălniceanu first studied at the Trei Ierarhi monastery in Iași. He was also taught by Gherman Vida, a monk. He finished his early education at a boarding school in Miroslava. During this time, he met future friends and leaders like Vasile Alecsandri, Costache Negri, and Alexandru Ioan Cuza. He became very interested in history and began studying old Moldavian writings.

With help from Prince Sturdza, he continued his studies abroad. He first went to Lunéville, France. Later, he studied at the University of Berlin in Prussia. In Berlin, he was greatly influenced by famous professors like Leopold von Ranke. Ranke taught him that politicians should understand history.

Kogălniceanu proudly said he was the first of Ranke's Romanian students. He also claimed to be the first to use the modern French words "Romanian" (roumain) and "Romania" (Roumanie). Before him, people often used "Moldavia(n)" and "Wallachia(n)".

In Berlin, he wrote his first books. These included a study on the Romani people and a history of Wallachia and Moldavia. Both were published in 1837. He was against Roma slavery in his country. He used examples of abolitionists from Western countries. He signed these early works with a French version of his name, Michel de Kogalnitchan.

Prince Sturdza became suspicious of Kogălniceanu's reform ideas. Because of this, Kogălniceanu could not finish his doctorate. He returned to Iași in 1838 and became a princely assistant.

Early Publications and Theater Work

Over the next ten years, Kogălniceanu published many works. These included essays, articles, and his first editions of Moldavian historical writings. He also started several magazines, such as Dacia Literară (1840) and Arhiva Românească (1840).

Both Dacia Literară and Foaie Științifică, which he edited with Alecsandri and Ion Ghica, were shut down by Moldavian authorities. They were seen as dangerous. Kogălniceanu also worked with Costache Negruzzi to print the works of Dimitrie Cantemir. He later got his own printing press. He planned to publish all Moldavian historical writings, including those by Miron Costin and Grigore Ureche. This project was completed in 1852.

In May 1840, he became co-director of the National Theater Iași. He worked with Alecsandri and Negruzzi. This theater became very popular, showing comedies based on French plays. However, it was also subject to Prince Sturdza's censorship.

In 1843, Kogălniceanu gave a famous speech on national history at the new Academia Mihăileană in Iași. This speech greatly influenced Romanian students and the generation of 1848. His speech was seen as a revolutionary idea.

The 1848 Revolution

Around 1843, Kogălniceanu's desire for change made him a suspect to Moldavian authorities. His history lectures were stopped in 1844. He was briefly jailed after returning to Iași. He then became involved in political activities in Wallachia, helping his friend Ion Ghica.

From 1845 to 1847, Kogălniceanu was in Paris and other Western European cities. He joined the Romanian student association there. He also became a Freemason, like many other reform-minded Romanians in Paris. In 1846, he visited Spain and wrote Notes sur l'Espagne.

When the European Revolutions began, Kogălniceanu was at the forefront of nationalist politics. He was seen as one of the leaders of the 1848 Moldavian revolution. Prince Sturdza ordered his arrest. Kogălniceanu avoided capture and wrote strong criticisms of Sturdza. By July, a reward was offered for his capture. He then fled to Bukovina.

Kogălniceanu became a key thinker for the Moldavian revolutionary group in exile. His important document, Dorințele partidei naționale din Moldova ("The Wishes of the National Party in Moldavia", August 1848), was a plan for a new constitution. It called for:

- Internal self-rule

- Civil and political freedoms

- Separation of powers

- Ending special privileges

- Ending forced labor (corvées)

- A union between Moldavia and Wallachia

He also published a "Project for a Moldavian Constitution". This explained how Dorințele could become real. In January 1849, he went to France and continued to support the Romanian revolution.

Reforms Under Prince Ghica

In April 1849, some goals of the 1848 Revolution were met. Grigore Alexandru Ghica, a supporter of liberal and unionist ideas, became Prince of Moldova. Prince Ghica allowed the revolutionaries to return. He appointed Kogălniceanu, Costache Negri, and Alexandru Ioan Cuza to government jobs.

Kogălniceanu began his work as a lawmaker under Prince Ghica. On December 22, 1855, a law he helped write was passed. This law ended slavery for privately owned Roma people. State-owned Roma had been freed earlier. Kogălniceanu said he personally inspired this law.

Prince Ghica also tried to improve the lives of peasants. He outlawed certain rents and said peasants could not be removed from their land. However, these measures did not last long. Kogălniceanu noted that landowners were too powerful, and the government was too weak.

Uniting the Principalities

Kogălniceanu's work for Romanian unity continued after the Crimean War. The 1856 Treaty of Paris placed Moldavia and Wallachia under the supervision of European powers. Kogălniceanu started the magazine Steaua Dunării in Iași. This magazine supported the union of the two lands.

He was elected to the ad hoc Divan, a new assembly where Moldavians could decide their future. He worked with Wallachian representatives to push for union and more self-rule. He also supported the idea of a "foreign prince" to rule.

After elections in September 1857, Kogălniceanu and his group supported Cuza for the Moldavian throne. This happened after the new ruler, Nicolae Vogoride, tried to rig the elections against the union. But the election results were canceled by Napoleon III and Queen Victoria.

Kogălniceanu played a key role in the Divan's decision to end boyar ranks and privileges. This meant that everyone would be equal under the law. It also brought universal military service and ended tax exemptions for nobles. This proposal passed with almost all votes on October 29, 1857. Kogălniceanu was proud that the whole nation accepted this reform. In November, his group also passed a law ending religious discrimination against non-Orthodox Christians in Moldavia.

On January 17, 1859, Kogălniceanu helped Cuza get elected in Moldavia. Then, Cuza was also elected in Wallachia on February 5. This led to the de facto (actual) union of the two countries, forming the United Principalities. When Cuza became ruler, Mihail Kogălniceanu gave an emotional speech welcoming him.

Land Reform and Monasteries

From 1859 to 1865, Kogălniceanu was often a cabinet leader in Moldavia. He then became Prime Minister of Romania. He was responsible for many reforms during Cuza's rule. One of his first terms ended in December 1860. This was due to a conflict over Cuza's plan to take over monastery lands.

In 1863, Cuza enforced the secularization (taking over by the state) of monastery lands. The land was then given to peasants. This was part of the land reform of 1864, which also ended forced labor.

Kogălniceanu is seen as the person behind this land reform. In 1860, a commission refused to create a basis for land reform. Instead, it only ended forced labor and allowed peasants to control their homes and some pasture. This project was supported by the Conservative leader Barbu Catargiu, but Kogălniceanu strongly criticized it.

After Catargiu's death, the "Rural Law" was passed by Parliament in June 1862. But Cuza did not approve it. Discussions then turned to taking land from Greek Orthodox monasteries in Romania. In late 1862, the state took over their income. In 1863, the Greek monks were offered money for their land.

On October 23, 1863, Cuza removed the old government. He appointed Kogălniceanu as Premier and Interior Minister. They decided to take over all Eastern Orthodox Church lands, both Greek and Romanian. This passed with almost all votes in Parliament. The Greek Church was offered more money, but they refused it. As a result, a large part of the country's farmland became available for land reform.

Cuza's Rule and Later Reforms

In spring 1864, Kogălniceanu's government proposed a big land reform. It suggested giving land based on how many oxen a peasant owned. Peasants would own their land after 14 yearly payments. This caused a big uproar in Parliament, which was mostly made up of nobles. They called the idea "insane."

On May 14, 1864, Cuza took power by force. He dissolved Parliament. Kogălniceanu read Cuza's decision in Parliament. Cuza then introduced a new constitution. This new system, along with a law for universal male suffrage (all men being able to vote), was approved by a public vote.

The new government passed its own version of the "Rural Law." This finally brought land reform and ended forced labor. Kogălniceanu's other actions as minister included:

- Establishing the Bucharest University.

- Introducing identity papers.

- Creating a national police force.

- Unifying the Border Police.

Despite these reforms, problems like a growing population and peasant debts meant the land reform did not fully solve the issues. This contributed to unrest in the countryside, leading to the Peasants' Revolt of 1907.

Cuza's new government, with Kogălniceanu's help, passed many reforms. These included adopting the Napoleonic code (a set of laws), creating public education, and establishing state monopolies on alcohol and tobacco. In early 1865, Cuza and Kogălniceanu disagreed, and Kogălniceanu was dismissed. After this, the government faced financial problems.

After 1863, Mihail Kogălniceanu's friendship with Vasile Alecsandri became strained. Alecsandri disliked politics and wrote critical pieces.

Carol I and the National Liberal Party

Prince Cuza was removed from power in February 1866. After a transition, the unified Principality of Romania was established under Carol of Hohenzollern. A new constitution was adopted. Two years later, Kogălniceanu became a member of the new Romanian Academy for his historical work.

From November 1868 to January 1870, he was again Minister of the Interior under Dimitrie Ghica. He helped set police uniform rules and investigated a murder case.

During this time, the Ghica government sought official recognition for the name "Romania." This was successful, but it worsened relations with Prussia. Kogălniceanu also tried to help Romanians living in Austria-Hungary.

Kogălniceanu continued to lead the liberal reform movement in Romania. In 1875, he started talks with the more radical liberal group. These talks led to the creation of the National Liberal Party on May 24, 1875. This was known as the Coalition of Mazar Pașa.

Kogălniceanu also signed a statement outlining the National Liberal goals. He was against his former colleague Nicolae Ionescu, who led a splinter liberal group.

Romania's Independence

As Foreign Affairs Minister in the Ion Brătianu government (1876, and again 1877-1878), Mihail Kogălniceanu was key to Romania joining the War of 1877–1878. This led to Romania declaring its independence. He first tried to get other countries to recognize Romania, but they refused.

When he returned to office, Kogălniceanu met secretly with Russian diplomats. He agreed to Russian demands in exchange for Romania joining the war. He convinced Prince Carol to accept the Russian alliance.

On May 9, 1877, Kogălniceanu gave a speech in Parliament. In this speech, Romania declared it was no longer under Ottoman rule. Prince Carol honored him as one of the first statesmen to receive the Order of the Star of Romania. Kogălniceanu also negotiated the terms for Romanian troops to join the war.

Over the next year, he worked to get Romania's independence recognized by all European countries. He traveled to Austria-Hungary and met the Foreign Minister. He found opposition to Romania's military efforts but got guarantees of border safety. The main challenge was convincing Otto von Bismarck, the German Chancellor, who was very hesitant about Romanian independence.

Congress of Berlin and Northern Dobruja

After the war, Mihail Kogălniceanu and Ion Brătianu led the Romanian delegation to the Congress of Berlin. They protested Russia's plan to exchange Northern Dobruja for Southern Bessarabia. Southern Bessarabia was a part of Bessarabia that Romania had received in 1856.

The Congress decided in favor of Russia's plan. This was mainly due to support from Austria-Hungary and France. Bismarck also put pressure on Romania. However, Kogălniceanu managed to get Snake Island back for Romania.

Romania also agreed to solve the issue of Jewish Emancipation. The government promised to grant citizenship to all non-Christian residents. Kogălniceanu tried to change this decision, but the Germans refused to compromise. This measure regarding Jewish people was not fully introduced until 1922–1923.

The exchange of territory was controversial in Romania. Many people thought it was unfair. Some even suggested returning to Ottoman rule. However, Kogălniceanu had secretly agreed to give up Southern Bessarabia earlier. He privately thought Northern Dobruja was a "splendid acquisition." But in Parliament, he had assured everyone that Southern Bessarabia was safe.

Kogălniceanu helped convince Parliament to approve the annexation of Northern Dobruja. He gave speeches that changed public opinion. He promised that the region would quickly become more Romanian. These speeches claimed Romania's right to the region dated back to the 1400s.

In 1879, as head of Internal Affairs again, Kogălniceanu began organizing Northern Dobruja's administration. He supported a special legal system for the region. This was a transition from Ottoman rule and aimed to make locals part of the Romanian mainstream. He encouraged Romanian farmers to move there. He also advised the local government to give more power to existing Romanian communities.

Final Years

Kogălniceanu later represented Romania in France (1880). He was the first Romanian envoy to Paris. The French state gave him the Legion of Honour. He also oversaw the first diplomatic contacts between Romania and Qing China.

Back in the newly proclaimed Kingdom of Romania, Kogălniceanu opposed giving more concessions to Austria regarding Danube river navigation. By 1883, he was known as a leader of a more moderate liberal group. He and his supporters criticized those who pushed for universal male suffrage. They argued that Romania's weak international position did not allow for such divisions.

After leaving political life, Kogălniceanu was President of the Romanian Academy from 1887 to 1889 (or 1890). He became very ill in 1886. In his final years, he edited historical documents and collected foreign documents about Romanian history. One of his last speeches at the academy summarized his career. In August 1890, he was saddened by the death of his friend Alecsandri.

Mihail Kogălniceanu died during surgery in Paris. He was buried in his hometown of Iași, at the Eternitatea cemetery.

Views

Liberalism and Political Beliefs

Mihail Kogălniceanu's work as a leader and thinker is praised for shaping modern Romania. Nicolae Iorga, a famous historian, called him "the founder of modern Romanian culture." He saw Kogălniceanu as someone who clearly imagined a free and complete Romania. He also saw him as the "redeemer of peasants" from forced labor.

Kogălniceanu was a democratic and nationalist politician. He combined liberalism with conservative ideas he learned in school. He was inspired by Prussian statesmen. He supported constitutionalism, civil liberties, and other liberal ideas. However, he put the nation's needs before individual ones.

Later in life, Kogălniceanu became more cautious about the French Revolution. He believed that "civilization stops when revolutions begin." His connections within Freemasonry helped Romanian causes abroad. They also played a part in Cuza's election.

Within the Romanian liberal movement, he was one of the few who connected modernization, democracy, and improving the lives of peasants. He praised Nicolae Bălcescu's work for peasants. He felt that the Wallachian uprising failed to achieve a lasting land reform.

Cultural Ideas

Kogălniceanu played a big role in fighting against nationalist extremes. He opposed attempts by some intellectuals to change the Romanian language too much by adding Latin or other Romance language influences.

He also helped bring spoken Romanian into the literary language. He believed in practical Westernization. He said, "Civilization never does banish the national ideas and habits, but rather improves them." He was against very fast cultural reforms. He believed that new ideas needed time to fit into Romanian culture.

As a historian, Kogălniceanu introduced some important ideas. He highlighted the 17th-century Wallachian Prince Michael the Brave as a unifier of Romania. He also claimed that Romanians were among the first Europeans to record history in their own language. His 1837 study of the Romani people is still seen as a groundbreaking work in its field.

As early as 1840, Mihail Kogălniceanu encouraged writers to find inspiration in Romanian folklore. He wanted them to create a "cultured literature." He and Alecu Russo laid the foundation for Romanian literary criticism.

Legacy

Family and Descendants

Mihail Kogălniceanu married Ecaterina Jora. They had more than eight children, including three boys. His eldest son, Constantin, studied law and worked in diplomacy. He started an unfinished work on Romanian history.

Ion, another son, was born in 1859 and died in 1892. He was the only one of Mihail Kogălniceanu's sons to have children. His family line continued into the 21st century. Ion's son, also named Mihail, created the Mihail Kogălniceanu Cultural Foundation in 1935.

Vasile Kogălniceanu, the youngest son, was involved in agrarian and left-wing politics in the early 1900s. He helped found Partida Țărănească (the Peasant Party). He campaigned for universal suffrage and Sunday rest. A statement he issued before the Peasants' Revolt of 1907 led to his imprisonment.

Vasile's sister Lucia studied in Dresden. Her third husband, Leon Bogdan, was a local leader of the Conservatives. Lucia was said to be the most intelligent of Kogălniceanu's children. She had eight children.

Memorials and Portrayals

Mihail Kogălniceanu's home in Iași is now a memorial house and public museum. His vacation house in Copou, Iași, known as Casa cu turn ("The House with a Tower"), was later bought by novelist Mihail Sadoveanu.

The historical writings edited by Kogălniceanu and Costache Negruzzi inspired many historical novelists. His relationship with the peasant representative, Ion Roată, is mentioned in a story by Ion Creangă. He is also the subject of a short writing by Ion Luca Caragiale.

Kogălniceanu is featured in many paintings. He appears in Costin Petrescu's fresco at the Romanian Athenaeum. There, he is shown with Cuza, who is giving a deed to a peasant. In 1911, a bronze statue of Kogălniceanu by Raffaello Romanelli was placed in Iași. In 1936, a monument dedicated to Kogălniceanu was built in Bucharest.

Actors have played Kogălniceanu in several Romanian films. These include Ion Niculescu in the 1912 film Independența României and George Constantin in Sergiu Nicolaescu's 1977 film Războiul Independenței. During the Communist era, Kogălniceanu's image was used in official propaganda.

Many places and landmarks are named after him. These include:

- Mihail Kogălniceanu Square and Mihail Kogălniceanu Boulevard in downtown Bucharest.

- The Mihail Kogălniceanu commune in Constanța County.

- The Mihail Kogălniceanu International Airport near Constanța. This airport also hosts a U.S. Military Forces base.

- The Mihail Kogălniceanu University in Iași, a private university founded in 1990.

In Lunéville, France, a plaque honors him.

Images for kids

-

Ion Ghica (seated) and Vasile Alecsandri in Istanbul (1855)

-

Opening session of the Romanian Parliament in February 1860

-

Russians enter Bucharest (The Illustrated London News, 1877)

-

Romanian reactions toward the Congress of Berlin (1878 cartoon)

See also

In Spanish: Mihail Kogălniceanu para niños

In Spanish: Mihail Kogălniceanu para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |