Ion Luca Caragiale facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ion Luca Caragiale

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 30 January 1852 Haimanale, Wallachia (today I. L. Caragiale, Dâmbovița, Romania) |

| Died | 9 June 1912 (aged 60) (Influenza) Berlin, German Empire |

| Pen name | Car., Ein rumänischer Patriot, Luca, i, Ion, Palicar |

| Occupation |

|

| Nationality | Romanian |

| Period | 1873–1912 |

| Genre | Drama, comedy, tragedy, short story, sketch story, novella, satire, parody, aphorism, fantasy, reportage, memoir, fairy tale, epigram, fable |

| Subject | Everyday life, morals and manners, politics, social criticism, literary criticism, music criticism |

| Literary movement | Junimism, Naturalism, Neoclassicism, Neoromanticism, Realism |

| Spouse | Alexandrina Burelly |

| Children |

|

| Signature | |

|

|

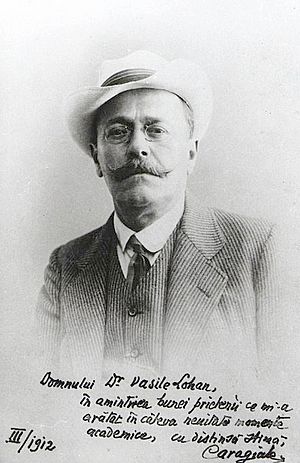

Ion Luca Caragiale (born January 30, 1852 – died June 9, 1912) was a famous Romanian writer. He wrote plays, short stories, and worked as a journalist. Many people consider him one of the greatest playwrights in Romanian literature. He is also known for his humor.

Caragiale was part of an important literary group called Junimea. His works often showed a mix of different styles, like Neoclassicism, Realism, and Naturalism.

Even though he wrote only a few plays, they are very important in Romanian theater. They often criticized Romanian society in the late 1800s. His famous comedies include O noapte furtunoasă, Conu Leonida față cu reacțiunea, and O scrisoare pierdută. He also wrote a serious play called Năpasta. Besides plays, Caragiale wrote many essays, articles, short stories, and even some poems. Some of his later stories, like La hanul lui Mânjoală and Kir Ianulea, were fantasy or historical tales.

Caragiale was interested in politics in the Romanian Kingdom. He often made fun of the liberal politicians in his satirical works. He had conflicts with powerful figures of his time. Later in life, he moved to Berlin and became more critical of Romanian politicians. His sons, Mateiu and Luca, also became writers.

Contents

- Who Was Ion Luca Caragiale?

- Early Life and Education

- Starting His Writing Career

- Working at Timpul and Claponul

- Inspector and Financial Struggles

- First Big Successes

- Theater Leadership and Marriage

- Conflicts with the Academy

- Moving Away from Junimea

- Moftul Român and Vatra

- Political Involvement and Epoca

- Universul and Business Ventures

- Moving to Berlin

- The 1907 Peasant Revolt

- Final Years and Legacy

- Writing Style and Ideas

- Political and Social Views

- Settings in His Works

- Characters in His Stories

- Types of Characters

- Literary Influences

- Cultural Impact

- Images for kids

- See also

Who Was Ion Luca Caragiale?

Ion Luca Caragiale came from a family of Greek origin. His family arrived in Wallachia (part of modern-day Romania) in the early 1800s. His grandfather worked as a cook for the royal court.

His father, Luca Caragiali, was a lawyer and judge. He married Ecaterina, whose family was from Brașov. Ion Luca also had a sister named Lenci.

Caragiale's uncles, Costache and Iorgu Caragiale, were important in early Romanian theater. They managed theater groups. Ion Luca's father had also performed with his brothers when he was younger.

Caragiale often talked about his family's humble beginnings. However, some researchers say his family had a good social standing. He usually kept quiet about his Greek background. His opponents sometimes used his foreign roots against him.

Some people, like literary critic Tudor Vianu, thought Caragiale's way of looking at life was very "Balkan" or "Oriental." This might have come from his family's background.

Early Life and Education

Ion Luca Caragiale was born in a village called Haimanale. He went to school in Ploiești. He learned to read and write at a local church school. He later studied literary Romanian with a teacher from Transylvania.

When he was seven, he saw big celebrations for the union of the Romanian lands. This event influenced his later political views. He finished high school in Ploiești but did not go to college.

Caragiale wanted to follow his uncles into theater. He learned acting from his uncle Costache in Bucharest. He also worked as a supernumerary actor (an extra) at the National Theater Bucharest. Since he couldn't find full-time acting work, he became a copyist for the Prahova County Tribunal around age 18. He kept his theater training a secret from many people.

In 1866, he saw the ruler, Alexandru Ioan Cuza, being removed from power. Caragiale supported the liberal movement and its ideas for a republic. In 1871, he saw the "Republic of Ploiești," a short attempt by liberals to remove the new ruler, Carol I. Later in life, as his views changed, Caragiale made fun of this event and his part in it.

He returned to Bucharest and worked as a prompter at the National Theater. He also read many philosophical books from the Enlightenment. He proofread for newspapers and worked as a tutor.

Starting His Writing Career

Caragiale started writing in 1873, when he was 21. He published poems and funny stories in a satirical magazine called Ghimpele. He used different pen names, like Car. and Palicar. After his father died in 1870, Caragiale became the main provider for his mother and sister.

He became involved with the radical and republican part of the liberal movement. He often attended their meetings and heard speeches from their leader. This helped him understand the populist way of speaking, which he later made fun of in his plays.

Some of his early articles were sarcastic. He made fun of other writers, including the poet Alexandru Macedonski. This started a long rivalry between them. Caragiale also wrote poems for Ghimpele.

In the following years, Caragiale wrote for newspapers of the new National Liberal Party. In 1877, he started his own satirical magazine, Claponul. He also translated French plays for the National Theater. He wrote articles criticizing the quality of Romanian plays and the common use of plagiarism.

Working at Timpul and Claponul

Caragiale started to move away from National Liberal politics after 1876. He joined the editorial team of Timpul, a main Conservative newspaper. He worked there with Mihai Eminescu and Ioan Slavici. They often had long discussions and even planned to write a Romanian grammar book together.

During this time, Timpul and Eminescu were strongly against the liberals. Romania also entered the Russo-Turkish War to gain full independence. Caragiale didn't focus much on Timpul during this period. He mostly worked on Claponul, his own magazine, which he wrote and edited by himself. He used Claponul to try out his writing style. Claponul stopped publishing in early 1878.

Inspector and Financial Struggles

In 1880, Caragiale published Conu Leonida față cu reacțiunea, a play about an uneducated man who thinks a revolution is happening. He also published his first memories from the theater world.

He traveled to Vienna with his friend Titu Maiorescu to see a play by William Shakespeare. When he returned, he was unemployed. In 1881, he left Timpul. However, he was appointed as an inspector for schools in Moldavia. He became good friends with other writers and thinkers from the Junimea group.

A year later, Caragiale was moved back to Wallachia as an inspector. But in 1884, he lost this job and faced financial difficulties. He took a low-paying job as a clerk. Around this time, he wrote a play called O soacră, which he later said was an early work from his youth.

In 1883, Caragiale was very sad to hear that Eminescu had become seriously ill. He also got involved in arguments among Junimea members. He criticized an older poet for making fun of Eminescu.

In 1885, Caragiale had the chance to inherit a lot of money from a wealthy relative. But he got involved in a long legal dispute with other relatives.

First Big Successes

Months later, his new comedy, O scrisoare pierdută (A Lost Letter), was first performed. It showed the conflicts between political groups, corruption, and empty speeches. It was an instant success and became one of the most famous Romanian plays. Maiorescu was happy about its success, seeing it as a sign that Romanian society was maturing.

Caragiale had a son, Mateiu, with Maria Constantinescu in 1885. He recognized Mateiu as his son.

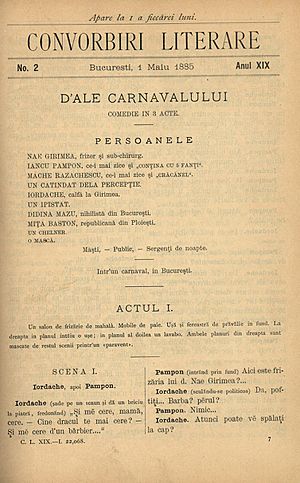

In the same year, his play D-ale carnavalului (Carnival Scenes), a lighter comedy about city life and love problems, was not well-received by the audience. Maiorescu defended Caragiale, publishing an essay praising his work. This article helped Caragiale gain public acceptance.

Theater Leadership and Marriage

Despite his past conflicts, Caragiale, still needing money, wrote for the National Liberal Party's newspaper. He also taught at a private high school. This period ended in 1888 when Maiorescu became Minister of Education. Caragiale asked to be appointed Head of Theaters, which meant leading the National Theater. After some hesitation, he got the job.

His appointment caused some debate because he came from a modest background, unlike previous leaders. Caragiale wrote an open letter explaining his plans for the state theaters, focusing on being organized and strict. He resigned at the end of the season to focus on writing.

In January 1889, he married Alexandrina Burelly, who came from a wealthy family in Bucharest. This helped improve Caragiale's social standing. They had two children: Luca (born 1893) and Ecaterina (born 1894). Later, Mateiu, his first son, came to live with them.

Conflicts with the Academy

In early 1890, Caragiale published his collected works and staged his rural tragedy Năpasta. He submitted both to the Romanian Academy for an award. However, two National Liberal members of the Academy, Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu and Dimitrie Sturdza, criticized his works. They said his plays lacked moral and national value.

Sturdza's speech led to the Academy voting against Caragiale (20 votes against, 3 in favor). This made Caragiale very angry. Years later, he wrote an article criticizing Sturdza and his supporters, saying they saw humor as "unholy" and "dangerous" to the nation.

Moving Away from Junimea

During this time, Caragiale published two memories about Eminescu, who had died in 1889. One was called În Nirvana (Into Nirvana), where he wrote about their early friendship.

Although he used to agree with Junimea's ideas, Caragiale started to turn against Maiorescu. He felt that the group had not supported him enough at the Academy. In 1892, he publicly criticized Maiorescu, which caused a permanent break between them. He also stopped writing for Convorbiri Literare, the Junimea magazine.

In late 1892, Caragiale published two books of prose, including his new stories Păcat, O făclie de Paște, and Om cu noroc. The next year, he started spending time with socialist groups and became good friends with the Marxist thinker Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea.

Financial problems forced Caragiale to become a businessman. In 1893, he opened a beer garden in Bucharest. He later bought a pub. He even thought about moving to Transylvania and becoming a teacher.

In 1894, Caragiale leased a restaurant at the train station in Buzău. His businesses often struggled, and he was close to bankruptcy. He eventually decided not to renew his contract.

Moftul Român and Vatra

With a socialist activist and an illustrator, Caragiale started the satirical magazine Moftul Român. It stopped for a while but was brought back in 1901. The magazine's name, meaning "the Romanian trifle" or "the Romanian nonsense," made fun of the cynicism and self-importance of modern Romanian society. Caragiale used it to show what he saw as a common national trait.

Caragiale also reconnected with writers from Transylvania. With George Coșbuc and Ioan Slavici, he founded the magazine Vatra in 1894. He published a funny story about how peasants communicate, a portrait of a politician, and a fairy tale. He also translated a story by Queen Elisabeth.

He also published short parts of classical works he had translated, asking readers to guess the authors. He wrote about Prince Ferdinand when he was very ill, showing his strong support for the Romanian monarchy. In 1898, he wrote an essay praising the actor Ion Brezeanu, who was famous for playing Caragiale's characters. Later that year, he published a new story, În vreme de război, a fantasy story set during the Russo-Turkish War.

Political Involvement and Epoca

In 1895, Caragiale, at 43, joined the Radical Party. He also wrote for its newspaper, Ziua. He briefly worked with the National Liberals again in the same year. He wrote articles attacking Junimea under different pen names.

This was a time of tension between Romania and Austria-Hungary. Caragiale criticized politicians who used nationalist feelings for their own gain. He wrote a short story about a trickster who pretended to be a nationalist writer in Transylvania. In 1897, he was angry when Romanian politicians gave in to Austro-Hungarian demands. He argued that Romanians living abroad were "essential" to the Romanian state.

In 1895, Caragiale joined the Radical group, which merged with the Conservative Party. He started writing for the Conservative journal Epoca and edited its literary section. He wrote about philosophy, saying he wasn't interested in any specific ideology. He also criticized Dimitrie Sturdza in an article.

He started to appreciate Junimea again, seeing it as important for Romanian culture. He also began to admire Romantic writers whom Junimea had criticized. He helped promote the works of young poets.

Universul and Business Ventures

Caragiale started working with Mihail Dragomirescu and contributed to the magazine Convorbiri Critice. Facing financial problems again, he took a government job in 1899, but it was cut in 1901. This made his conflict with Sturdza even worse.

At the same time, Caragiale wrote for the daily newspaper Universul. His articles formed his collected short prose volume, Momente și schițe, which included satirical pieces.

He continued his business career. In 1901, he opened his own company, Berăria cooperativă, which took over the Gambrinus pub. It became a meeting place for writers and artists.

In early 1901, to celebrate Caragiale's 25 years in literature, his friends held a banquet. Hasdeu, despite their past differences, sent a letter calling him "Romania's Molière". However, in 1902, the National Liberal majority in the Romanian Academy refused to give an award to Momente și schițe.

Moving to Berlin

After receiving a large inheritance, Caragiale became quite wealthy. He later lost some of it but became rich again after his sister Lenci died in 1905, leaving him a lot of money. This caused tension with his son Mateiu, who felt cheated.

Caragiale wanted to move to a Western European country for a more comfortable life and to be closer to cultural centers, especially for classical music. In 1905, he and his family moved to Berlin, Germany. This was unusual because he knew very little German.

The family lived in an apartment and later a villa. Caragiale joked about his move, calling it "the white loaf of exile." He stayed connected with Romanian students and young people in Berlin. He often traveled to Leipzig and visited Beethoven's house in Bonn.

He also returned to Romania sometimes. He wrote a poem making fun of King Carol I on his fortieth year in power. He continued to publish works in various newspapers and magazines.

His later works were mostly letters with other writers and thinkers. Caragiale planned to write a new play combining characters from his two most famous comedies, but he never finished it.

The 1907 Peasant Revolt

In 1907, Caragiale was deeply affected by the Romanian Peasants' Revolt and its violent suppression. He wrote a long essay condemning the land policies of both liberal and conservative governments. This essay, 1907, din primăvară până în toamnă (1907, From Spring to Autumn), criticized major social problems in Romania.

The essay was first published in German under the name Ein rumänische Patriot ("A Romanian patriot"). It was later printed in Romania under Caragiale's own name. The essay was very popular, selling about 13,000 copies.

This event led to a political offer for Caragiale to join the Conservative Party, but he refused. He had become disappointed with traditional political groups. In 1908, he joined the Conservative-Democratic Party. He briefly returned to Romania to campaign for this party.

Final Years and Legacy

Starting in 1909, Caragiale again wrote for Universul. His fantasy story Kir Ianulea, about Bucharest in the early 1800s, was published. Other stories used themes from One Thousand and One Nights. Another work, Calul dracului, was a rural story about temptation.

His last collection of writings, Schițe nouă (New Sketches), was printed in 1910. He helped create a new private theater in Bucharest.

By this time, Caragiale became close to a new generation of Romanian thinkers in Austria-Hungary. He supported the poet and activist Octavian Goga, who had been jailed by Hungarian authorities. Caragiale wrote that such actions could increase tensions in the region. He even visited Goga in jail.

He also wrote for a journal in Arad, supporting the National Romanian Party. In 1911, he attended a cultural celebration in Blaj. He also saw one of the first flights by the Romanian aviation pioneer Aurel Vlaicu. In January 1912, when he turned 60, Caragiale declined a formal celebration.

Caragiale died suddenly at his home in Berlin. The cause of death was a heart attack. His son Luca said that on that night, his father was rereading William Shakespeare's Macbeth.

Caragiale's body was brought back to Bucharest and buried in Bellu cemetery on November 22, 1912. His longtime rival, Alexandru Macedonski, was saddened by his death and praised his humor.

Writing Style and Ideas

Caragiale's writings are considered the best examples of Romanian theater. His style is seen as a mix of 19th-century Classicism and Realism. He followed classical rules for plays and rejected Romantic ideas. He believed in "art for art's sake," meaning art should be beautiful for its own sake, not to teach a lesson.

His role in Romanian literature is compared to famous writers like Honoré de Balzac in France and Nikolai Gogol in Russia. Critics say his irony helped create a unique urban literature in Romania.

Caragiale's writing is very focused on dialogue. Language is central to his work, often making up for a lack of detailed descriptions. He liked to shorten texts to their main points. Sometimes, he added personal or thoughtful parts to his stories, especially his later fantasy works.

He was very precise about his writing. He believed that writing was an art that needed to be learned carefully. He often used humor to make his points.

Political and Social Views

Caragiale was very interested in human nature. He often criticized grand theories and their effect on Romanian society. He found humor in the ideas of the 1848 Wallachian revolutionaries and how they were used by the National Liberal Party.

He believed there was a big difference between the first generation of liberal activists and the new liberal leaders. He thought the new leaders were full of hypocrisy and empty talk. He often made fun of their speeches.

Caragiale's criticism of the liberal movement was partly inspired by the Junimea group. He saw liberals as promoting populism and empty words. He believed that liberal-inspired literature was "spinach" (meaning worthless).

Views on Nationalism

Ion Luca Caragiale strongly criticized antisemitism, which was common among some politicians. He believed that the Jewish community should be fully integrated into Romanian society and have equal rights. He even tried to write a law proposal for this.

He also criticized nationalist ideas and liberal education. He wrote a funny pamphlet about a group called the "Green Romanians" who believed nations should always fear each other. He was against attempts to change the Romanian language to make it sound more Latin. He created a character, Marius Chicoș Rostogan, who made fun of liberal educators and "Latinists" from Transylvania.

However, some people believe that a young Caragiale did support nationalist liberal policies and wrote some anti-Jewish articles.

Conservatism and Tradition

In some of his early writings, Caragiale criticized the Conservative ideas and their Junimist leaders. He said that Titu Maiorescu and Petre P. Carp were "boyars" who cared only about their social class.

Despite briefly working with mainstream Conservatives, Caragiale probably never fully supported them. He only hoped they would bring about reforms. When they didn't, he supported Take Ionescu's new party.

Caragiale was different from other major writers of his time, like Eminescu and Alexandru Vlahuță. They wanted to return to rural life and peasant traditions. Caragiale made fun of old-fashioned language used by some writers.

However, Caragiale was also a strong supporter of tradition. He valued his Orthodox Christian faith. He believed in luck and destiny. He also had some phobias, like fear of fire and disease.

Caragiale and Modernism

Ion Luca Caragiale was mostly critical of new literary experiments and Modernism. He often made fun of Alexandru Macedonski's style, especially after he started using Symbolism. His own poems often made fun of Romanian Symbolist groups.

He refused to publish some modern poetry, saying it wasn't real poetry. He also criticized the works of modern playwrights like Henrik Ibsen, even though he hadn't read their plays.

However, Caragiale was not completely against new art. He admired a free verse poem by the Symbolist Ion Minulescu. He also admired the paintings of Ștefan Luchian, a Postimpressionist artist.

Caragiale and the Left

In his later years, Caragiale moved towards the Left. He stayed in touch with socialists but had mixed feelings about their goals. Some of his writings were published in socialist journals.

He sometimes made fun of socialist activists. However, his support for George Panu meant he returned to radicalism. He campaigned for universal suffrage (everyone being able to vote) and land reform.

Caragiale sometimes made ironic comments about the Marxist ideas of his friend Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea. He believed that observation and quick thinking were better than deep philosophical theories. He also made fun of a new way of thinking called Poporanism, which mixed socialism with traditionalism.

He remained friends with Dobrogeanu-Gherea for most of his life. He was interested when Dobrogeanu-Gherea helped refugee sailors during a scandal in 1905. He tried to convince the Dobrogeanu-Gherea family to move to Berlin.

Settings in His Works

Caragiale knew a lot about the social environments, customs, and ways of speaking of his time. He traveled a lot and studied everyday life in Romania. He was a very social person.

Many of his major works are set in rural areas. These include Năpasta, În vreme de război, and La hanul lui Mânjoală. However, Caragiale is most famous for his urban themes, which are the background for most of his best works.

He showed the city in all its stages and moods, from nightlife to quiet midday heat, from noisy slums to fancy tea parties. He was especially proud of how he described a "corner of a slum" in one of his stories.

Caragiale preferred Bucharest and provincial towns that were influenced by Central European culture. He also liked the world of the Romanian Railways, and many of his stories are related to it.

Characters in His Stories

Caragiale often pretended to be part of the environment he was observing. He would adopt the manners and speech patterns of the people he met. This helped people open up to him and share their stories. He was a great actor and ironist, making people unsure if he was serious or joking.

Direct criticism was rare in Caragiale's fiction. He sometimes showed himself to be sentimental and modest. This, along with his Christian beliefs, contributed to his calm and often understanding view of society.

However, some critics believed that Caragiale actually disliked the people who inspired his works.

There is a clear difference between Caragiale's comedies and his Momente și schițe (Moments and Sketches). His comedies are driven by situations, while his sketches show his unique view of society. This change happened as Romania moved from a traditional world to a more stable and modern one.

Types of Characters

Caragiale's Realism focused on creating specific types of characters. Many critics say his works provided some of the first truly believable characters in Romanian literature. He looked for "social types" rather than just general human types.

The universal human nature was important to Caragiale, but he didn't make it immediately obvious. For example, in O scrisoare pierdută, he chose the senile politician Agamiță Dandanache to win the election because it gave the play more depth. Caragiale said Dandanache was "more stupid" and "more of a scoundrel" than other characters.

Momente și schițe gave less insight into characters' feelings. His longer stories, however, did show emotions and details about their physical appearance. Caragiale usually didn't focus on the psychological background of his characters, except in a few serious plays or when making fun of psychological techniques.

Maiorescu liked how Caragiale balanced personal details with general traits. For example, Leiba Zibal, a Jewish character in O făclie de Paște, was seen as representing the Jewish people as a whole, similar to Shakespeare's Shylock.

Allegorical Characters

One of Caragiale's early character types is the young man deeply in love, who uses dramatic and romantic phrases. Rică Venturiano in O noapte furtunoasă is a good example. Caragiale used this theme so well that it took another generation for youthful love to be shown in a non-comedic way in Romanian literature.

Venturiano also criticizes liberal journalists and lawyers. He writes long, exaggerated articles for republican newspapers. A more complex character is Nae Cațavencu in O scrisoare pierdută. He uses liberal language to attack politicians with angry remarks and blackmail. He pretends to be a progressive politician and gathers teachers and state employees around him. The only one who can stop him is Agamiță Dandanache, an old revolutionary. Dandanache, though old and confused, has a lot of experience in blackmail.

Conu Leonida față cu reacțiunea shows how republican ideas affect an audience. Leonida, a retired man, believes a "Red" republic will give everyone a salary and cancel debts. He is convinced a revolution can't happen because authorities have banned shooting weapons in the city.

Many of Caragiale's characters represent social classes or regional identities. One famous character is Mitică, who represents ordinary people from Bucharest or Wallachia. He is often hypocritical and superficial, using common phrases and quickly dismissing important things.

The teacher Marius Chicoș Rostogan, who appears in several sketches, represents Transylvanian people living in Romania who supported the liberal ideas. His speeches, which Caragiale uses to make fun of liberal education, focus on memorizing unimportant details.

Cetățeanul turmentat (the Drunken Citizen), an unnamed man in O scrisoare pierdută, symbolizes simple townspeople who are confused by politics. He is ignored by important people. Like the police agent Ghiță Pristanda, he has no personal ambition and will support whoever is in power to keep his job.

In many of his short stories, Caragiale explores the glamorous but superficial impact of modernization on high society. Characters in these stories often resemble each other, showing the general traits of wealthy people.

Other Character Traits

Anxiety is a main theme in several of Caragiale's writings. His detailed description of growing terror in O făclie de Paște was highly praised. In some stories, characters become desperate when they can't handle changes in their lives. This happens to characters like Leiba Zibal and Stavrache.

Fear of upcoming events affects the main characters in Conu Leonida față cu reacțiunea. Jealousy drives the characters in D-ale carnavalului to act irrationally. Iancu Pampon and Mița Baston are determined to uncover their partners' love affairs. Their frantic search mixes real clues with imagined ones, passionate anger with sad thoughts, and violent threats with moments of giving up.

Many of Caragiale's writings show conversations between clerks on their time off. These talks are usually awkward discussions about culture or politics. Several characters falsely claim to be friends with important politicians or to have inside information. They are often worried about political events but quickly adapt.

Caragiale himself appears in many of his works. He created the famous background character Nenea Iancu ("Uncle Iancu"), based on his nickname and his habit of visiting beer gardens. He introduces some of his characters in Momente și schițe as personal friends. He even admitted that a love affair in one of his plays was partly based on his own experience as a young man.

Literary Influences

Ion Luca Caragiale was influenced by many writers. He knew the works of playwrights from William Shakespeare to the Romantics. He was especially impressed by French comedies. He followed the rules of "well-made plays."

He said that Cilibi Moise, a Jewish peddler and writer of short, witty sayings, was an early influence. He also admired Anton Pann, whose work inspired some of his own stories. Nicolae Filimon wrote short stories that are seen as simpler versions of Caragiale's character Rică Venturiano.

Caragiale was likely familiar with the comedies written by his uncles, Costache and Iorgu Caragiale. Another influence was Vasile Alecsandri, whose plays criticized Westernization. However, Caragiale's work was more complex.

He was amused by the character Robert Macaire, who was a comedic figure. He bought cartoons by French artists Honoré Daumier and Paul Gavarni. Some of Daumier's caricatures are very similar to Caragiale's texts.

Caragiale was also aware of new trends in literature. The works of Émile Zola were a source of inspiration. Some critics believe that Năpasta and O făclie de Paște show the influence of Fyodor Dostoevsky. Later in life, Caragiale discovered the works of Anatole France, whose humanist themes influenced his fantasy writings.

His fantasy works have been compared to Shakespeare's late romances. Some believe they were inspired by Edgar Allan Poe. Kir Ianulea used Niccolò Machiavelli's novel as a source, showing Caragiale's interest in Renaissance literature.

Cultural Impact

Caragiale's writings accurately recorded the Romanian language as it was spoken in his time. He captured different dialects, slang, and verbal habits. This was partly because he had a good ear for music.

Caragiale had a lasting impact on Romanian humor and how Romanians see themselves. His comedies and stories created many famous phrases that are still used today. However, his sharp criticism sometimes led to his work being less emphasized in schools.

His writing techniques influenced many 20th-century playwrights and directors. His short stories and novellas inspired other authors. Some people even see Caragiale as a predecessor of Absurdism. Outside Romania, Caragiale's work is less known, partly because it's hard to translate and stage.

Many authors wrote memoirs about Ion Luca Caragiale. He is also depicted in several fictional works. In 1948, he was elected to the Romanian Academy after his death.

In 2002, the 150th anniversary of his birth was celebrated as the "Caragiale Year" in Romania. Theater festivals are held in his honor. Many Romanian films and TV shows are based on his works.

The Bucharest National Theater is named after him. Several schools also bear his name. Statues and busts have been raised in his honor. In 2007, he was named "the most portrayed writer" by the Guinness Book of Records for having over 1,500 drawings in one exhibit.

His childhood home in Haimanale was opened to the public in 1979. Streets, avenues, and parks in many Romanian cities are named after him.

Images for kids

-

The Russian Army in Bucharest, print in The Illustrated London News (1877).

-

We are all honest people, let's embrace one another, and let this be over with, 1834 print by Honoré Daumier.

See also

In Spanish: Ion Luca Caragiale para niños

In Spanish: Ion Luca Caragiale para niños

| James B. Knighten |

| Azellia White |

| Willa Brown |