Alexandru Macedonski facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alexandru Macedonski

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 14 March 1854 Bucharest, Wallachia |

| Died | 24 November 1920 (aged 66) Bucharest, Kingdom of Romania |

| Pen name | Duna, Luciliu, Sallustiu |

| Occupation | Poet, novelist, short story writer, literary critic, journalist, translator, civil servant |

| Period | 1866–1920 |

| Genre | Lyric poetry, rondel, ballade, ode, sonnet, epigram, epic poetry, pastoral, free verse, prose poetry, fantasy, novella, sketch story, fable, verse drama, tragedy, comedy, tragicomedy, morality play, satire, essay, memoir, biography, travel writing, science fiction |

| Literary movement | Neoromanticism, Parnassianism, Symbolism, Realism, Naturalism, Neoclassicism, Literatorul |

| Signature | |

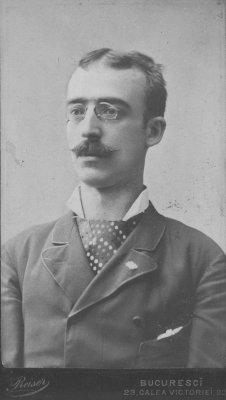

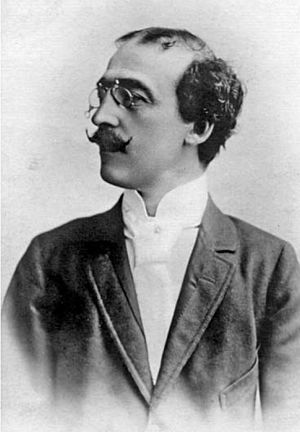

Alexandru Macedonski (born March 14, 1854 – died November 24, 1920) was an important Romanian poet, writer, and literary critic. He is best known for bringing French Symbolism to Romania and leading the early Symbolist movement there.

Macedonski was a pioneer of modernist literature in Romania. He was the first Romanian writer to use free verse, a style of poetry without a regular rhyme or rhythm. Some even say he was the first in modern European literature to do so. Many critics consider him one of Romania's greatest poets, second only to the national poet Mihai Eminescu.

He started his career as a Neoromantic poet. Later, he explored Realism and Naturalism, which focused on showing life as it truly was. He then adapted his style to Symbolism and Parnassianism, which emphasized beauty and art for art's sake. Macedonski often tried to become famous in the French-speaking world, but he wasn't very successful.

Besides his writing, Macedonski also worked as a public official. He served as a prefect (a type of local governor) in the Budjak and Northern Dobruja regions in the late 1870s. As a journalist, he was involved in many debates and often changed his political views. His most important publication was Literatorul (meaning "The Literator" or "The Writer"). This magazine became a center for his literary group and later for the Symbolist movement in Romania.

Macedonski came from an important and noble family. His father, General Alexandru Macedonski, was a Defense Minister. His grandfather, Dimitrie Macedonski, was a leader in the 1821 uprising. Both his son Alexis and grandson Soare became well-known painters.

Contents

- Alexandru Macedonski's Early Life

- Starting His Writing Career

- His Time as a Public Official

- Leading the "Literatorul" Magazine

- Travels and New Ideas

- Later Years and World War I

- His Later Life and Death

- Alexandru Macedonski's Writings and Style

- His Lasting Impact

- Works Published During His Life

- Images for kids

- See Also

Alexandru Macedonski's Early Life

His Family Background

Alexandru Macedonski's family arrived in Wallachia in the early 1800s. They might have been of South Slav (Serbian or Bulgarian) or Aromanian origin. They claimed to be descended from Serb rebels in Ottoman-controlled Macedonia.

His grandfather, Dimitrie, and his great-uncle, Pavel, took part in the 1821 uprising against the Phanariotes, who were Greek rulers. Dimitrie later sided with another group during the revolt. Both brothers served in the Wallachian military. The family was recognized as part of Wallachia's nobility. Dimitrie married Zoe, whose father was a Russian or Polish officer. Their son, also named Alexandru, became a military and political leader. He joined the unified Romanian army after Alexander John Cuza became ruler of the united Romania. Pavel and Mihail, his great-uncle and uncle, were also amateur poets.

Macedonski's mother, Maria Fisența, came from a noble family in Oltenia. She may have been descended from Russian immigrants. Her adoptive father, Dumitrache Pârâianu, left her and her husband the Adâncata and Pometești estates.

The poet and his father were not happy with these family stories. They claimed to be from Lithuanian nobility, which researchers now believe was not true. Even though they were Romanian Orthodox, the Macedonskis preferred this story. However, Alexandru Macedonski also seemed proud of his Balkan roots. Some historians believe his background helped enrich Romanian culture.

Childhood and Education

The family moved often because of General Macedonski's military postings. Alexandru Macedonski was born in Bucharest and was the third of four children. As a young child, he was often sick and nervous.

In 1862, his father sent him to school in Oltenia. He spent most of his time in the Amaradia region. He later felt nostalgic for this area and wanted to write a series of poems about it. He attended the Carol I High School in Craiova and graduated in 1867.

His father was a strict commander. He was once dismissed from his role as Defense Minister by ruler Cuza. This caused a political scandal. Macedonski remained against the new ruler, Carol I, who replaced Cuza. As a young man, he tried to bring attention to his father's cause. His father died in September 1869, and the family suspected he was murdered by political rivals.

Starting His Writing Career

In 1870, Macedonski left Romania and traveled through Austria-Hungary, visiting Vienna, Switzerland, and possibly other countries. He was supposed to prepare for the University of Bucharest but spent his time enjoying himself and having romantic adventures. Around this time, he started developing a writing style influenced by Romanticism. He published his first poems in 1870 in the journal Telegraful Român.

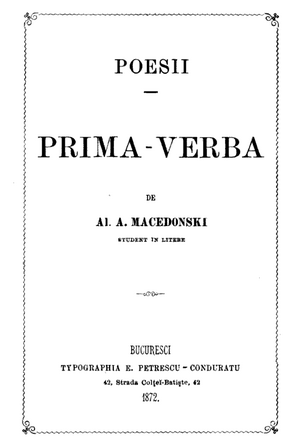

The next year, he went to Italy, visiting Pisa, Florence, and Venice. He faced money problems and illness during this trip. He claimed to have attended university lectures in Italy, but this is not certain. He returned to Bucharest and enrolled in the Faculty of Letters, but he rarely attended classes. In 1872, he published his first book, Prima verba (Latin for "First Word").

Macedonski became interested in politics and journalism. In 1874, he founded a literary society in Craiova called Junimea. This name was similar to a conservative group he would later argue with. He also helped start Oltul magazine, which supported liberal ideas. In this magazine, he published his first travel writing and short stories.

At 22, he wrote his first play, a comedy called Gemenii ("The Twins"). Around this time, another young journalist, Ion Luca Caragiale, started making fun of Macedonski in articles. This was the beginning of a long rivalry between the two writers.

His Time as a Public Official

In March 1875, Macedonski was arrested for speaking out against the government. He had called for people to "rise up with weapons" against the government and the ruler. He was held in Văcărești prison for almost three months. The liberal press supported him, and he was found not guilty in June.

Later in 1875, when a liberal government came to power, Macedonski started a career in public service. He was appointed Prefect of the Bolgrad region, which was then part of Romania. During this time, he published his first translation, Lord Byron's epic poem Parisina. He also wrote original works like Ithalo and Calul arabului ("The Arab's Horse"). His time as prefect ended when the Russo-Turkish War began. He was removed from office for not allowing Russian volunteers to pass through his region.

Still wanting to work in journalism, Macedonski founded several short-lived patriotic magazines. Romania gained independence after the Russo-Turkish War. Macedonski remained committed to the anti-Ottoman cause.

By 1879, he had switched between the National Liberals and the Conservatives several times. That year, he was appointed administrator of the Sulina area and the Danube Delta. During this short period, he visited Snake Island in the Black Sea. His love for this place later inspired his fantasy novel Thalassa, Le Calvaire de feu and the poem Lewki.

Leading the "Literatorul" Magazine

The 1880s marked a turning point for Alexandru Macedonski. People started seeing him as a nonconformist and unique. This might have made him feel like a "poet who doesn't fit in," a concept described by French poet Paul Verlaine. He aimed to promote "social poetry," which combined poetry with political activism.

In January 1880, he launched his most important magazine, Literatorul. This magazine became the center of his diverse literary group and later the local Symbolist school. Literatorul often challenged the views of the conservative Junimea literary society. Macedonski criticized their leader, Titu Maiorescu, and especially the poet Mihai Eminescu.

In November 1880, two of Macedonski's plays, Iadeș! ("Wishbone!") and Unchiașul Sărăcie ("Old Man Poverty"), premiered at the National Theater Bucharest. He was also appointed Historical Monuments Inspector. However, his plays were not very successful.

In 1881, Macedonski published a new collection of poetry called Poezii. He tried to get accepted by the Junimea group and Maiorescu. He even read his poem Noaptea de noiembrie ("November Night") to them. While some praised it, Maiorescu was not impressed.

Travels and New Ideas

After losing his administrative job, Macedonski faced financial difficulties. He moved to the outskirts of Bucharest. He continued to enjoy luxury items, though his source of income was a mystery.

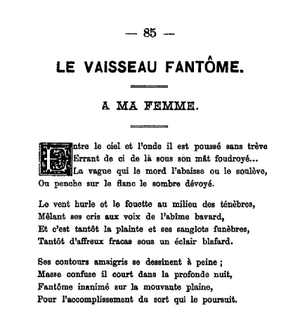

In 1884, Macedonski traveled to Paris. There, he connected with French writers and started contributing to French Symbolist magazines. His collaboration with La Wallonie made him one of the original European Symbolists. This shift to Symbolism was also influenced by his love for French culture. He became opposed to King Carol I, who had become King of Romania in 1881. Macedonski preferred the German Empire, while Carol I favored France. In January 1885, after returning from his trip, he announced he was leaving public life. He claimed that German influence had "conquered" Romanian culture and repeated his view that Eminescu's poetry was not good.

Literatorul stopped being published for a while, though new issues appeared sometimes until 1904. Macedonski tried to start other magazines, but they were all short-lived. In 1887, he published his Naturalist short novel Dramă banală ("Banal Drama"). He also completed one of his most famous poems, Noaptea de mai ("May Night"), part of his Nights series.

By 1888, he was again supporting a different political group. He wrote for the Românul newspaper. In 1894, he spoke at a political rally and supported the rights of ethnic Romanians and other groups in Austria-Hungary.

His literary idea at the time was called Poezia viitorului ("The Poetry of the Future"). It promoted Symbolist writers. Macedonski started writing "instrumentalist" poems, which focused on musical sounds and onomatopoeic elements. This experimental style was later made fun of by Ion Luca Caragiale. Macedonski tried to make peace with Caragiale, but their conflict continued.

In 1893, Literatorul published parts of his novel Thalassa. Macedonski also launched a daily newspaper called Lumina ("The Light"). He worked with Cincinat Pavelescu, a famous writer of short, witty poems. They co-wrote the 1893 verse tragedy Saul, based on the Biblical hero. The play was performed at the National Theater but was not successful. Two years later, Macedonski and Pavelescu became known as pioneers of cycling. Macedonski was very enthusiastic about the sport.

Later Years and World War I

Macedonski published a new book of poetry, Excelsior (1895 and 1896 editions). He also founded Liga Ortodoxă ("The Orthodox League"), a magazine where Tudor Arghezi, who became a very famous Romanian writer, made his debut. Macedonski praised Arghezi for being a great poet at a young age. Liga Ortodoxă also published articles against Caragiale, which Macedonski signed with the pen name Sallustiu.

In 1895, his story Casa cu nr. 10 was translated into French. Two years later, Macedonski published French translations of his earlier poems in a volume called Bronzes. While it received a positive review from Mercure de France magazine, it was largely ignored by the French public.

By 1898, Macedonski was again facing money problems. Between then and 1900, he studied mysterious and unusual topics. He believed that people could control death with words and gestures. He also tried to invent a machine to put out chimney fires. Later, his son Nikita invented nacre-treated paper, which is sometimes wrongly attributed to his father.

Macedonski and his followers often met in Bucharest cafés. He had a table reserved at Kübler Coffeehouse, where he would sometimes loudly mock other poets. His literary club at his house became like a mystical group, with Macedonski acting as a leader. The meetings were held in a candle-lit room, and new members went through special rituals. This was supposedly inspired by groups like the Rosicrucians and Freemasonry.

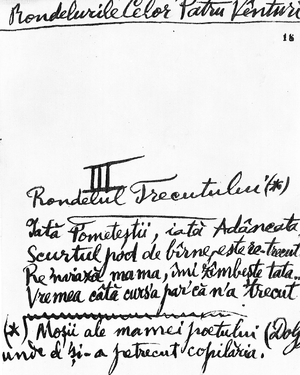

He founded Revista Critică ("The Critical Review"), which also closed quickly. He published the poetry volume Flori sacre ("Sacred Flowers"). In 1914, his novel Thalassa was published. In September 1914, Macedonski gave a speech praising France, which had just entered World War I. He also started writing his first rondels and finished a play about the poet Dante Aligheri.

In 1916, Romania joined the Entente Powers in World War I. However, during the period of neutrality, Macedonski had changed his mind and supported the Central Powers. In 1915, he published the journal Cuvântul Meu ("My Word"), which he wrote entirely himself. It criticized France and urged Romania not to join the war. This change in his views puzzled many people.

Macedonski further upset public opinion during the war when the Central Powers occupied Bucharest. While many officials and citizens moved to Iași, Macedonski stayed in Bucharest. He reportedly faced extreme poverty during the occupation.

His Later Life and Death

Literatorul started printing again in June 1918 after Romania signed a peace treaty with the Central Powers. After the Romanian government regained control of Bucharest, Macedonski faced some challenges. However, he tried to adapt. In December 1918, Literatorul celebrated Romania's expanded territory as a success. Macedonski even thought about running for a seat in the new Parliament, but he never did. Literatorul was revived one last time in 1919.

His health worsened due to heart disease. He also had trouble accepting his old age. His last work published during his lifetime was the pamphlet Zaherlina, completed in 1919 and published in 1920.

Confined to his home by illness, Macedonski continued to write poems. Some of these are known as his Ultima verba ("Last Words"). Alexandru Macedonski died on November 24, 1920, and was buried in Bucharest's Bellu.

Alexandru Macedonski's Writings and Style

General Characteristics

Alexandru Macedonski often changed his writing style and ideas, but some things remained constant in his work. Many people believe his writing had a very strong visual quality. The poet Cincinat Pavelescu said Macedonski was "Poet, therefore painter; painter, therefore poet." Traian Demetrescu remembered that Macedonski had dreamed of becoming a visual artist.

Macedonski was very creative in his use of the Romanian language. He added many new words from different Romance sources to his poetry. He also liked to compare nature with artificial things in his writing. His language mixed new words with unusual ones, some of which he made up himself.

Critics note that while Macedonski's work changed over time, it sometimes reached great artistic heights and sometimes was just average. At his best, he is considered one of Romania's classic writers.

Early Poems and Stories

Young Macedonski belonged to the late Romanian Romanticism movement. He was influenced by earlier Romanian poets and by Romanian folklore. This influence is clear in Prima verba, which contains poems he wrote when he was very young, some as early as age twelve. These poems show his rebellious spirit and often talk about his own life, like the death of his father.

During his time at Oltul magazine (1873–1875), Macedonski published many poems. Some of these made fun of Carol I without naming him. After his arrest, he wrote Celula mea de la Văcărești ("My Cell in Văcărești"), where he tried to joke about being in prison.

Later, when he was in the Budjak and Northern Dobruja, his poems became less focused on current events. He was especially inspired by Lord Byron. In Calul arabului ("The Arab's Horse"), Macedonski explored exotic settings and used symbols that would later appear in other Romanian poems. His poem Ithalo was set in Venice and focused on betrayal and murder. Other poems were epic and patriotic, celebrating Romanian victories in the Russo-Turkish War. One of these poems, Hinov, might make Macedonski the first modern European poet to use free verse, even before the French Symbolist Gustave Kahn. Macedonski himself later claimed this and called his technique "symphonic verse" or "Wagnerian verse."

Macedonski also wrote his first prose works while editing Oltul. These included the travel account Pompeia și Sorento (1874) and a sad prison story called Câinele din Văcărești ("The Dog in Văcărești", 1875). His short comedy Gemenii was his first play. In 1876, he wrote a short biography of Cârjaliul, a famous outlaw from the early 1800s. His 1877 story Așa se fac banii ("This Is How Money Is Made") was a fable about fatalism and the Muslim world. It told the story of two brothers, one hard-working and one lazy, where the lazy one gets rich by chance. His verse comedy Iadeș! borrowed its theme from the Persian collection Sindipa.

Realism and Naturalism in His Work

By the 1880s, Macedonski developed his "social poetry" idea, which was part of Realism. He explained it as a reaction against the style of Lamartine. It also showed his brief connection with the Naturalist movement, which was a more extreme part of Realism. Traian Demetrescu noted that Macedonski admired the works of French Naturalist and Realist writers like Gustave Flaubert and Émile Zola.

With Unchiașul Sărăcie, Macedonski brought Naturalist ideas into drama. He also worked on his own version of William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, where the two main characters die in each other's arms. Another play, 3 decemvrie ("December 3"), used Naturalist elements to retell an older German play. In contrast, his play Cuza-Vodă was mostly Romantic, showing Alexander John Cuza's political mission being supported by legendary figures in Romanian history.

Between 1880 and 1884, Macedonski thought about making French his main language for writing. One of his French poems from this time, Pârle, il me dit alors ("Speak, He Then Said to Me"), shows his desire to live abroad.

Embracing Symbolism

In the early 1900s, Macedonski and other Symbolist poets from Wallachia were seen as different from those in Moldavia. Macedonski supported Symbolism for most of his life and later claimed to have been one of its first supporters.

In his poem Ospățul lui Pentaur ("The Feast of Pentaur"), the poet thought about civilization itself. During this period, Macedonski also explored the connections between Symbolism, mysticism, and unusual beliefs.

He also started publishing his "instrumentalist" Symbolist poems. This type of experimental poem was influenced by the ideas of René Ghil and Remy de Gourmont. It also showed Macedonski's belief that music and spoken words were closely related.

Famous Poems: "Excelsior"

Even though he was interested in new ideas, Macedonski often used a more traditional style in his Excelsior volume. This book included Noaptea de mai ("May Night"), which is considered "one of the most beautiful poems" in Romanian literature. It celebrates spring and uses folk themes, famous for its repeated line, Veniți: privighetoarea cântă și liliacul e-nflorit ("Come along: the nightingale is singing and the lilac is in blossom").

Like Noaptea de mai, the poem Lewki (named after and dedicated to Snake Island) also shows intense joy and the healing power of nature. The book also returned to Levant settings and Islamic images, especially in Acșam dovalar. Another notable part of the volume is his short "Modern Psalms" series, including the poem Iertare ("Forgiveness").

Later Stories and Final Poems

In his prose, Macedonski focused on descriptions or entered the world of fantasy literature. These stories, many collected in Cartea de aur, include memories of his childhood in the Amaradia region. They also feature nostalgic descriptions of the noble families of Oltenia, idealized portrayals of Cuza's rule, and a look back at the end of Rom slavery. The most famous among them is Pe drum de poștă ("On the Stagecoach Trail"), a story that is a thinly disguised memoir about a young Alexandru Macedonski and his father.

Especially in the 1890s, Macedonski was a fan of Edgar Allan Poe and Gothic fiction. He wrote a Romanian version of Poe's story Metzengerstein and encouraged his students to translate similar works. He also used "Gothic" themes in his own prose. Influenced by Jules Verne and H. G. Wells, Macedonski also wrote several science fiction stories. One of these, Oceania-Pacific-Dreadnought (1913), describes a civilization facing a crisis.

Ultima verba ("Last Words"), his very last poems, show him accepting himself and are valued for their calm or joyful view of life and human achievements.

His Lasting Impact

Macedonski's Influence

Alexandru Macedonski often said that future generations would see him as a great poet. Many of his most dedicated students, whom he encouraged, are considered less important writers by critics.

Macedonski's oldest son, Alexis, became a painter. His son Soare also followed in his footsteps and received praise from art critics. Soare's short career ended in 1928, before he turned nineteen, but his works have been shown in many exhibitions. Another of Alexandru Macedonski's sons, Nikita, was also a poet and painter.

Macedonski's career inspired many other authors.

Later Recognition

Macedonski was truly recognized as a classic writer only after his death, between the two World Wars. A final book of his poems, Poema rondelurilor, was published in 1927.

His status as one of Romania's great writers became stronger later in the 20th century. By this time, Noaptea de decemvrie had become one of the most famous literary works taught in Romanian schools. Even during the early years of Communist Romania, when Symbolism was criticized, Macedonski's work was still viewed favorably. Later, Marin Sorescu, a well-known modern poet, wrote a playful tribute to Macedonski's Nights cycle. Also, Noaptea de decemvrie partly inspired Ștefan Augustin Doinaș's poem Mistrețul cu colți de argint.

Macedonski's prose influenced younger writers. In neighboring Moldova, Macedonski influenced the Neosymbolism movement. In 2006, the Romanian Academy made Alexandru Macedonski a member after his death.

Macedonski's poems had a big impact on Romania's popular culture. During the communist era, Noaptea de mai was turned into a popular song. Tudor Gheorghe, a singer-songwriter, also used some of Macedonski's texts as lyrics for his songs.

Works Published During His Life

- Prima verba (poetry, 1872)

- Ithalo (poem, 1878)

- Poezii (poetry, 1881/1882)

- Parizina (translation of Parisina, 1882)

- Iadeș! (comedy, 1882)

- Dramă banală (short story, 1887)

- Saul (with Cincinat Pavelescu; tragedy, 1893)

- Excelsior (poetry, 1895)

- Bronzes (poetry, 1897)

- Falimentul clerului ortodox (essay, 1898)

- Cartea de aur (prose, 1902)

- Thalassa, Le Calvaire de feu (novel, 1906; 1914)

- Flori sacre (poetry, 1912)

- Zaherlina (essay, 1920)

Images for kids

See Also

In Spanish: Alexandru Macedonski para niños

In Spanish: Alexandru Macedonski para niños