Mount Edziza volcanic complex facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Mount Edziza volcanic complex |

|

|---|---|

Mount Edziza, one of the main volcanoes of the Mount Edziza volcanic complex.

|

|

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 2,787 m (9,144 ft) |

| Prominence | 1,750 m (5,740 ft) |

| Listing | List of volcanoes in Canada Ultra |

| Geography | |

| Location | British Columbia, Canada |

| Parent range | Tahltan Highland |

| Topo map | NTS 104G/10 |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | 7.5 million years |

| Mountain type | Complex volcano |

| Volcanic arc/belt | Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province |

| Last eruption | Unknown; younger than 700 |

The Mount Edziza volcanic complex is a huge group of volcanoes in northwestern British Columbia, Canada. It's about 38 kilometers (24 miles) southeast of a small town called Telegraph Creek. This area is part of the Tahltan Highland, which has plateaus and smaller mountains.

A volcanic complex means it's not just one volcano, but many different types! Here, you can find shield volcanoes, calderas (big bowl-shaped craters), lava domes, stratovolcanoes, and cinder cones.

Most of the Mount Edziza volcanic complex is inside a large park called Mount Edziza Provincial Park. This park, named after Mount Edziza, was created in 1972. It helps protect the amazing volcanic features and important cultural sites in northern British Columbia. The Mount Edziza volcanic complex is far away from cities. There are no roads directly into it, so you can only reach it by trails. The easiest way to get there is from British Columbia Highway 37 and a road from Dease Lake to Telegraph Creek.

Geology

How it Formed

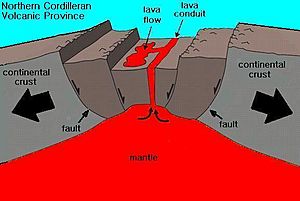

The Mount Edziza volcanic complex started forming about 7.5 million years ago. It has been growing ever since! Like other volcanoes in this part of British Columbia, Mount Edziza was created because the Earth's crust is slowly pulling apart. This is called continental rifting.

Imagine the North American Plate (the huge piece of Earth's crust we live on) being stretched. It's pulling apart at about 2 centimeters (0.8 inches) per year. This stretching happens because the Pacific Plate is sliding north along the Queen Charlotte Fault. As the crust stretches, it cracks. Hot, melted rock called magma rises up through these cracks. This magma creates gentle lava eruptions, which build up the volcanoes.

This stretching has been happening for at least 20 million years. It has formed a line of volcanoes called the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province. This line stretches from the Alaska-Yukon border down to near Prince Rupert, British Columbia. Some of these volcanoes are sleeping but could wake up. Two of them have erupted in the last few hundred years. People from First Nations and gold miners saw these eruptions.

Volcano Types

The Mount Edziza volcanic complex covers about 1,000 square kilometers (386 square miles). It's Canada's second largest area of young volcanic activity. Only Level Mountain is bigger.

Four main volcanoes are found here: Armadillo Peak, Spectrum Range, Ice Peak, and Mount Edziza. These volcanoes sit on top of a huge, wide shield volcano. This shield volcano is like a broad lava plateau, about 65 kilometers (40 miles) long and 20 kilometers (12 miles) wide. It's mostly made of hardened lava flows. You can also see many smaller cinder cones scattered around. The edges of this plateau have steep cliffs called escarpments. These cliffs show layers of black lava.

Stratovolcanoes

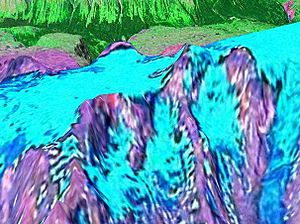

The tall, cone-shaped volcanoes here are called stratovolcanoes. They are built by many eruptions of thick, slow-moving lava. These volcanoes often have explosive eruptions. They pile up layers of volcanic ash, cinders, and chunks of rock. The stratovolcanoes at Edziza are made of a rock called trachyte. They haven't erupted for thousands of years. This has allowed erosion to wear them down, creating rocky ridges.

Calderas

Calderas are large, circular depressions. They form when a volcano's magma chamber (the underground pool of melted rock) empties out. If a lot of magma erupts, the ground above the chamber can't hold its weight and collapses. This creates a big "ring fault" around the edge of the chamber. The largest caldera at Mount Edziza is about 6 kilometers (3.7 miles) wide. This is small compared to most calderas, which are usually at least 25 kilometers (15.5 miles) wide. The eruptions that formed these calderas produced trachyte and a white, soda-rich rock called comendite.

Lava Domes

Edziza's rounded, steep-sided lava domes are built by eruptions of very thick, light-colored magma, like trachyte. This magma is too thick to flow far, so it piles up around the vent, forming a dome shape. The magma is thick because it has high levels of silica. These domes can grow slowly for months or years, reaching hundreds of meters (hundreds of feet) tall. Sometimes, gas pressure can build up inside, leading to explosive eruptions. If part of a lava dome collapses, it can create a pyroclastic flow. This is a super-hot mix of gas, ash, and pumice that rushes down the volcano.

Cinder Cones

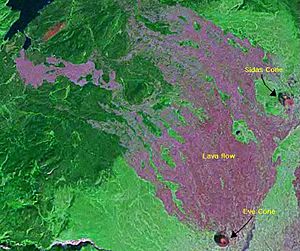

The steep, cone-shaped cinder cones at Edziza are formed by "lava fountain" eruptions. These eruptions shoot out particles and blobs of lava from a single opening. As the gas-filled lava flies into the air, it breaks into small pieces. These pieces cool and fall around the vent, forming a cone. Edziza's cinder cones have bowl-shaped craters at their tops. They rise more than a hundred meters (hundreds of feet) above the surrounding land.

Eve Cone, a black cinder cone in the complex, is one of Canada's most famous and best-preserved cinder cones.

Shield Volcanoes

Edziza's shield volcanoes are made almost entirely of fluid lava flows. Lava flows out in all directions from a central vent, creating a wide, gently sloping cone that looks like a warrior's shield lying on the ground. They are built slowly by thousands of thin, runny lava flows that spread out over long distances. Sometimes, lava flows quietly from long cracks in the ground, called fissure vents. This has flooded the area, forming Edziza's wide lava plateau.

Subglacial Mounds

Subglacial mounds are unusual volcanoes that formed when eruptions happened under thick glacial ice. This happened during the Pleistocene and early Holocene periods, when glaciers covered this region. The eruptions weren't hot enough to melt a hole straight through the ice. Instead, they formed mounds of volcanic rock fragments and pillow-shaped lava deep beneath the ice. When the glaciers melted, these unique volcanoes were revealed.

Eruptive History

The volcanoes at Mount Edziza were built in five main stages. Each stage began with dark lava flows, forming flat shield volcanoes. Then, lighter-colored magma erupted. This cycle happened because hot magma from deep inside the Earth rose to the surface. The lighter-colored magmas are similar to those found in the most powerful eruptions on Earth.

Armadillo Peak Period

The first stage of activity happened seven million years ago, creating Armadillo Peak. Today, it's an eroded remnant of a small caldera. It has steep-sided lava domes and thick layers of light-colored lava flows and ash.

Spectrum Range Period

The second stage began three million years ago. A large, circular lava dome called the Spectrum Range was formed. This is the southernmost of the four main volcanoes. It's over 10 kilometers (6 miles) wide. It's named for its many colorful rocks, which show how much the area has changed over time. This activity ended 2.5 million years ago.

Ice Peak Period

Ice Peak, which is 2,500 meters (8,200 feet) high, started forming 1.6 million years ago. This was when the large Cordilleran Ice Sheet (a huge glacier) began to melt away. Ice Peak is a stratovolcano. Its eruptions produced both dark and light-colored lava flows and rocks. These mixed with melted ice to create mudslides. As Ice Peak grew, glaciers formed on its high slopes. These glaciers carved valleys into the volcano.

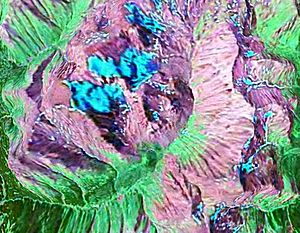

Mount Edziza Period

The fourth stage of activity began one million years ago. This created Mount Edziza itself, which is the northernmost of the four main volcanoes. It's a steep-sided stratovolcano and the largest peak in the complex, standing 2,787 meters (9,144 feet) tall. Mount Edziza has a circular, ice-filled caldera at its summit. Many glaciers cover Mount Edziza, including the Tencho Glacier. Piles of pillow lava and hyaloclastite (rocks formed under ice) are found on its sides.

Central Volcano Flank Period

The fifth and final stage of eruptions happened from smaller vents on the sides of the four main volcanoes. This started 10,000 years ago, when some glacial ice was still present. These early eruptions formed tuff rings (low, flat volcanoes). Later, about 30 small cinder cones formed, mostly made of dark lava. These include famous ones like Eve Cone. These cinder cones are very young, some forming after the year 700.

The Snowshoe lava field and the Desolation lava field are areas of young lava flows. The Desolation lava field is the largest, covering 150 square kilometers (58 square miles). The longest lava flow is 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) long.

There's also a mysterious pumice deposit called Sheep Track Pumice. Pumice is a light, airy volcanic rock. We don't know where this pumice came from, but it looks like it's less than 500 years old. This pumice shows that powerful explosive eruptions could still happen at Mount Edziza.

Current Activity

The Mount Edziza volcanic complex is one of Canada's volcanoes that has shown recent earthquake activity. This suggests that there might still be active magma systems deep underground, meaning future eruptions are possible.

The most recent volcanic activity at Mount Edziza has been hot springs. Several hot springs are found on the volcano's western side. These springs are near the youngest lava fields and are likely connected to the most recent eruptions. These hot springs were very important to the local Tahltan people.

Hot springs happen when groundwater flows deep into the Earth and gets heated by hot rocks or magma. The hot water then rises back to the surface. Sometimes, these springs release steam and gases, which are called fumaroles.

Human History

Indigenous People

As far back as 10,000 years ago, the Tahltan First Nations people used obsidian from the Mount Edziza volcanic complex. Obsidian is a natural glass formed when lava cools quickly. It's very sharp when broken, so the Tahltan used it to make tools and weapons. They also traded this obsidian with people as far away as Alaska and northern Alberta.

Two interesting rock formations in the area are the Tahltan Eagle and Pipe Organ Mountain. The Tahltan Eagle is very important spiritually and culturally to the Tahltan people.

Geologic Studies

Scientists have studied and mapped this volcanic area for many years. The first detailed studies of Mount Edziza were done in the early 1970s by a group from the Geological Survey of Canada, led by scientist Jack Souther.

Souther's work helped show how important and large the region was. He suggested that many eruptions happened under ice. His studies helped lead to the creation of Mount Edziza Provincial Park in 1972. The park was set up to protect the volcanic features. Later, the park's size was almost doubled to protect more of the area.

More recent studies have built on Souther's work. Mount Edziza is very important for studying volcanoes that erupt under ice. Its lavas show evidence of how thick the ice was in the past, which helps scientists understand ancient ice ages. Students from universities have done fieldwork here, studying things like how lava flows under ice and the types of rocks found in the area. This helps us learn more about Earth's history and volcanic processes.

Monitoring

Currently, the Geological Survey of Canada doesn't monitor the Mount Edziza volcanic complex very closely. The existing network of seismographs (instruments that detect earthquakes) is too far away to give a clear picture of what's happening deep inside the volcano. These seismographs are mainly for monitoring regular earthquakes. They might detect a big increase in activity, but this might only give a warning just before a large eruption.

To truly understand a volcano, scientists need to study its past eruptions. Every volcano has its own pattern of how it erupts. Knowing this helps predict future eruptions.

It's important to monitor volcanoes in Canada because eruptions could affect nearby areas. However, there isn't enough detailed information about Canadian volcanoes to fully assess the risks.

Other ways to study volcanoes include hazard mapping. This shows a volcano's past eruptions and helps guess what might happen in the future. Canada doesn't have a large program for volcanic hazards. Information is collected by different scientists. More is known about the Mount Meager massif in southwestern British Columbia, but less is known about Mount Edziza and other volcanoes in the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province.

The seismograph network in Canada has been around since 1975. But for good volcano monitoring, you need at least three seismographs within about 15 kilometers (9 miles) of the volcano, or even closer. This helps scientists detect small earthquakes and figure out where they are happening, including their depth. This kind of close monitoring helps predict eruptions and reduce risks. Right now, the closest seismograph to Mount Edziza is 88 kilometers (55 miles away). This distance makes it harder to accurately detect and understand volcanic activity.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Complejo volcánico monte Edziza para niños

In Spanish: Complejo volcánico monte Edziza para niños

| Calvin Brent |

| Walter T. Bailey |

| Martha Cassell Thompson |

| Alberta Jeannette Cassell |